Anna Levi is a writer of dual Grenadian and Trinidadian citizenship, born August 29, 1984, and now living in Tacarigua and Trincity, Trinidad. Her first novel, Madinah Girl (Karnak House, 2016), won Special Mention in the 2016 Bocas Literary Awards competition. Levi’s narrative style is both lyrical and rude, combining a Caribbean realist literary tradition with the creole nation language spoken in the streets and rumshops of Trinidad. Levi has been hailed by literary icon Earl Lovelace for taking readers into the “bruising, multi-religious, multi-ethnic churnings in the underbelly of Trinidad.” Her second novel, “Nowherians,” continues to develop Levi’s vision of life among young people on the margins of contemporary Trinidad. Please see the excerpted chapter, “Rich Gold,” in Aquifer as well.

Kevin Meehan for The Florida Review:

Madinah Girl is a very strong and uniquely voiced debut novel. How did you come to be a writer, and what motivates you to write?

Anna Levi:

My life! It has been a flamboyant, emotional, and a kind of surrealistic adventure—from selling avocados and empty Carib beer bottles in rumshops, begging for food and money in Mosques for Juma, running around half-naked and bare-feet on the hot-pitched streets of Tacarigua, selling my mother’s aloo pie in primary school in order to buy red mango and tamarind balls, pitching marbles with orphans, roasting pigeons, doves, and cashew nuts on the fireside for lunch, listening to Lord Kitchener from a jukebox, liming with cows in the cemetery, attending funerals of children who died from drowning in the river, catching butterflies, flying kite, playing cricket, frightening children with Lagahoo stories, bursting bamboo and lighting deyas for divali, eating orisha food my mother always warned me about, and so many other tragic-buoyant, memorable things I have done in my life. The world of children—their voices/language, their livelihood, their social and emotional status, their environment and the underworld culture—is the biggest motivation for me to write. From childhood I was always telling and writing stories. When, much later, I began to study literature formally for a degree and reading people like Selvon, Naipaul, Michael Anthony’s Green Days by the River, and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, I realized I had the material to develop this interest. Acting as Atticus Finch in a high school production of Mockingbird gave me a breakthrough—when I realized that as a writer one could assume any identity.

TFR:

Other critics have compared your work to the social realism of Harold Sonny Ladoo, you yourself have spoken to me many times about the importance of Jean Rhys as an inspiration, and I myself was frequently reminded of Merle Hodge and especially her short story, “Inez,” that appeared in Callaloo some years back. What do you make of these sorts of comparisons?

Levi:

I began Madinah Girl before I’d read any Ladoo and I haven’t yet read Merle Hodge’s “Inez.” If you’re looking for comparisons, I think someone like Reinaldo Arenas, in terms of childhood, poverty, and abuse as content, subject matter, and also his self-declared peasant identity, might be more productive. Shani Mootoo’s Cereus Blooms at Night would be another comparable text, in its treatment of sexual abuse and trauma. While I can now see similarities between Ladoo’s irreverent attitude, his settings and language, he wrote almost exclusively about the rural Indo-Trini community, whereas my focus is on all the indigenous and immigrant communities in Trinidad and then beyond in the intra-Caribbean diaspora (Guyana, Grenada, etc). Jean Rhys—whose narrative I identified with and who first showed me that life experience can be structured in literary form—is definitely a major literary inspiration—but mostly because of Voyage in the Dark. Although I’ve studied Caribbean literature, because of my rootsy upbringing which brought me into direct contact with the range of Trini cultural and religious practices, I tend to treat my texts as extensions of these practices, rather than neatly formulated linear narratives. Creole language, dance, and song are integral to my writing. I write from a Creole position with no apologies.

TFR:

What are some other inspirations—and not necessarily literary icons—people, places, or things that had an impact on the writing of Madinah Girl that we might not expect?

Levi:

When I was fifteen years old, I went to Grenada. I was on my uncle’s estate, and I was wandering the estate because I was trying to see how big it was. And I saw an orisha woman living in a shack, very poor, she was squatting on my uncle’s property. Very very very very VERY poor place, I’m telling you, I took pictures, and she had a blind son, a very big boy he looked like about twenty-something and he was a blind boy, and he was walking around and looking for his brother and sister. They were small. And so I’m hearing the man—the boy—calling out for his brother and sister, and he’s blind. I saw him with a stick, so I said, “Who’re you looking for?” and he said, he’s looking for his sister. So, I went off to look for his sister, and his eleven-year-old sister was being raped by her twelve-year-old brother. And I stopped him. And the girl was crying, tears, and that really woke me up to literature to want to write about it. So after that every year I went to Grenada, and I used to check on the girl and see if she was fine and okay. I think her brother died, but that girl being sexually abused by the brother really was painful for me, and I had to write about it. And in the same village when I walk down the road, I’m seeing men drinking alcohol, drinking rum in rumshops, and they’re really having a good time, I’m talking about father’s drinking rum in rumshops, like heavy rum, and getting drunk, a pig roasting in the back, they’re eating pork. And the girl’s being raped in the bush there, and the father is drinking alcohol in the front here, so it’s the whole landscape and the village life that really woke me up to write about it.

I grew up in a poor (but not depressing) and racially divided environment. My parents are an interracial couple with a big age difference. My siblings and I were often rejected by primary schools because of our father’s skin color, religion, social/economic, and marital status. For seven years, I attended a primary school which included orphans. The orphanage was across the road from the school, also close to where I live, and we shared the same church. The school and the orphanage were one. Children confided in me. From secrets about sexual, physical, and verbal abuse to their lives of their incurably insane and alcoholic birth parents to the luck of being saved by the bell. I was also a victim of child sexual abuse. At the age of eight, I felt psychologically homeless and emotionally parentless. So there was a special kind of bond with these friends of mine. We created our own kinship… many of these kids have been demonized by their own society. These children are my biggest inspiration and you’ll come across it in “Nowherians,” the novel I’m currently working on.

TFR:

What’s at stake in the title, Madinah Girl?

Levi:

Madinah means city in Arabic, “city girl.” It’s a young girl who’s looking to be enlightened. She has been suffering for so long, and she leaves home to find enlightenment, love, everything. Madinah is also the holy city of spiritual enlightenment. It’s a multicultural place where people interact and fuse. I love Arabic language… especially through music. I’ve learnt a lot about the culture through the music, like “Mastool” or “High” in English, by the Egyptian singer Hamada Helal.

TFR:

So, carrying on with the topic of children and your interest in children and children’s stories, the coming-of-age novel is arguably a primary genre in Caribbean literature. I wanted to ask you how you see Madinah Girl as either fitting into that slot or what makes it unique as a Caribbean bildungsroman?

Levi:

Well, it’s the language that makes it unique. I write about the language of the people, it’s a nation language, so you look at other novels, and it’s really bourgeois and you can laugh it off, and then you move on with life. But when you look at Madinah Girl, you can’t laugh that off. It’s realer. So when you get someone in their own language who reads Madinah Girl, they recognize one time what is right and what is wrong, what’s going on in a village, you know, people are sick, people are dying, all the issues. They are conscious, it makes them conscious. And, you know, I did an experiment. I gave a few people, a few uneducated people, Madinah Girl to read and after they read it they were like, “Oh, my God, I know someone who did this.” They were conscious of other stories and stories in their own life.

TFR:

Typically in the bildungsroman, the character finds a place in society at the end, but I don’t know that Maria, the protagonist in Madinah Girl, finds that place in society at the end. It seems as if it’s open-ended at the end, if not fragmented and shattered.

Levi:

Yeah, because we are a fragmented people. Caribbean people, we are fragmented and we are made of all different kinds of things. I wanted to leave it open because it continues, it’s like a discourse, something that’s going on still. I didn’t want to put an end to it, it’s still going on.

TFR:

Does her story continue in “Nowherians”?

Levi:

Yeah, it continues in “Nowherians,” but it goes back to children. It goes back to their lives at a tender age, much younger than Maria in Madinah Girl. I think in both books, “Nowherians” and Madinah Girl, it’s a nation of language, people, and culture. It’s that nation that people do not want to know about, especially the bourgeoisie.

TFR:

And what about “Nowherians”? How did you come up with that title?

Levi:

That is a working title, but I really love it. “Nowherians” means “children of Nowhere” and most of the things I’m writing about in the book concern children who feel abandoned or not loved or they feel bad because of their treatment. So, children of Nowhere, they’re lost, they are lost.

TFR:

When I read Madinah Girl, I found the issues of chronology, time, and development of the protagonist to be extremely interesting, difficult, and bordering on chaos even. What are your thoughts about chronology?

Levi:

Well, I want to jump. I believe in the gap. You know, I did a workshop with Marlon James, and he said that gap is important. Sometimes when you write a story line and it’s too consecutive it’s sometime boring and sometimes you’re stuck. I just wanted to jump, because I just wanted to show the importance of the lives of Maria and even her brother Pablo, I wanted to show the important parts of their lives, and the effects and all the chaos in their lives. I didn’t want to have to jaunt through a chapter that’s settled. I wanted to pinpoint the chaos, like “This is it, I’m nailing it. I’m not hiding it at all, I’m nailing it, and this is the fucking chaos.”

TFR:

What’s up with the shift from the first person to the third person in one of the chapters, I think it’s titled “Walima”?

Levi:

I sometimes want to be like God in the book. I want to use my skill, to tell it in the first person, but then I want to step aside and look at a character. I change to third person when I don’t feel comfortable in the character’s shoe, when I don’t feel comfortable with the character. So in “Nowherians,” I am in most of the characters’ shoes. So I’m changing and each character is different. We have three characters—Donna, Bruno, and Keisha—and I am Donna in one chapter, Keisha in another chapter, and Bruno in yet another. I feel so comfortable it’s like I’m writing a story I can experience and I can tell. But third person is when I don’t feel comfortable enough to be in the first person, so I kind of step aside. Writing in the third person allowed me to be omniscient. I wanted to show and tell with many eyes and with an unobstructed view by switching the point of view. It’s like sitting on top of the world with a microscope!

TFR:

Can you say something about your writing process?

Levi:

Writing “Nowherians” depresses me. I went to two interviews yesterday—child brides—then before I write I get so depressed. All morning I am in tears, then I go into exile and write for days. I interviewed a woman who was a child bride, and it made me realize something. When I was eleven, a Muslim woman brought me to my “future husband”… it was the same man I ended up with after leaving the woman I lived with. In Hindu and Muslim culture, men are given their brides as young as nine. This woman I interviewed was married at age eleven, she met her husband at age five. Her mother chose her husband. Her mother was Indian and her father was African, but her family didn’t accept the mixing of the races so she was considered a bastard child and her mother married her off to get rid of her and the “shame” she (the mother) brought into the family. She is in her forties and has fourteen kids. Some died. Her husband beat the shit out of her. He is dead now, but she lives alone because all her kids were taken in by people. If you see the poverty the woman lives in… I can write about it without taking any pics, because I grew up with women like that—women who marry young. These same women who marry young, often do the same… they bring husbands for young girls… a fucking cycle. And I remembered, the same Muslim woman who gave me my first lover, she was in an arranged marriage at age eleven.

TFR:

How would you characterize the Trinidad that you write about in Madinah Girl, the world of Orange Grove, Trin City, Dinsley Village, Calcutta Village, rumshops, masjids, and brothels in St. James? This is not the sort of place you typically see depicted in literature, so how do you talk about this Trinidad?

Levi:

Through experiences, one, and then when I’m writing a chapter I revisit the place and look at it then and now. I look at images, I talk to people. I look for the filthy stuff, the dirty stuff, the things that people do not want to talk about or do not want to write about or hear about. You know, you come to Trinidad, you eat bake and shark, you drink coconut water, or you go to the beach and you don’t know how many kids are in the orphan home, are abandoned by their drug addicted parents, you don’t know about children being sold off into shops to work for people. So I wanted to look at that, at the bitterness behind all of this sweetness. It’s very bitter, and when you come out of the beautiful zone of Trinidad and you go into the ghetto, and you see a young boy with a gun, and you see a young girl being a prostitute, and you see an old-old woman who is digging in a dustbin and smoking crack cocaine, you wonder where this began. You know, it just didn’t happen now.

TFR:

I would say the flora and the fauna and the food, the things that people drink and the clothes that they wear, and the landscapes around them, all of that is brilliant and sharply drawn in the book—

Levi:

—and the vagrants!

TFR:

I want to ask about the range of languages in the novel. In particular, how would you talk about the language of your protagonist, Maria, when she is functioning as a frame narrator versus the vernacular spoken language of both Maria herself and the other characters? How do you handle the issue of narration versus spoken language as a writer?

Levi:

It’s kind of difficult sometimes because when I’m writing the dialogue and I go into the narrator, I kind of fall back and I wanna stick to the damn Creole English, right, I wanna stick to the language? But it’s challenging so that’s why I have an editor who edits for me, to keep me on track, but it’s sometimes difficult to maneuver both. Maria, like most Trinis, works the linguistic continuum from Creole to Trini Standard English, sometimes all the way to Standard English. When she’s framing narrative she’ll tend towards the more “proper” register, whereas when she’s speaking like some of the other characters, she’s more comfortable with Creole, although even then, because we’re dealing with a traumatized character, she may almost subconsciously slide between registers. One very important point has to be kept in mind when engaging with Madinah Girl. This is a series of events/episodes recalled through the consciousness of a character who is not stable, which is why it veers between the sublime and ridiculous, the horror and the beauty. This fluidity is also reflected in the language, which refuses like Maria’s fragmented consciousness to be standardized or regulated. Some publishers and critics fail to grasp this basic dynamic and have attempted to get me to tidy it up, to make it logical, which would entirely defeat its essence. My editor even tried to retain some of the incongruities of Maria’s thought processes, which are expressed in a strange combination of a creolized literary Standard English, resulting in the unique voice. Once you start standardizing and attempting to force this text into conventional forms, you kill the voice. The voice, the language, reflect the damaged consciousness not only of Maria and other characters but indeed of postmodern neo-colonial T&T. The text, the narratives it carries are a cry against denial (of the realities presented) and a Creole assertion and subversion of the impositions of a postcolonial society unable to free itself from the jumbies of colonialism, respectability, and bourgeois/globalized values. If readers and critics find this confusing, so much the better, because the reality is itself highly confused and conflicted.

TFR:

So what’s at stake there? Why not just use nation language to voice the narrator?

Levi:

For the narrator? Well, I want to do that in the future. It’s a good experiment!

TFR:

Your experience suggests that, if you write in nation language, a local audience is there to receive it.

Levi:

Yeah, mostly the poor people. I have great feedback from my supporters, so, I just write, you know, in my language, so that my people could understand, and other people who aren’t my people are welcome to understand the culture.

TFR:

I want to ask you another question about the style or technique of your writing. Because it does have a social realism aspect to it, which is both extremely beautiful and extremely harsh from paragraph to paragraph or even sentence to sentence. But, against the social reality, you have these utopian desires of the protagonist. This opposition or tension is also a formal/stylistic issue in which harsh and obscene language is pitted against unexpected lyricism, and adjectives or adverbs often work to modify objects and actions in surprising ways. So, what about those oppositions in your writing?

Levi:

Maria doesn’t get to be a child when she is around her family. With her father, she doesn’t get to be a child. So she has to fake things in order to get out of things and not go to the church. So I wanted the style to reflect that and change when she’s around different kinds of people.

The opposition (brutality vs. beauty, innocence) reflects Maria’s struggle with the harshness of her position and her innocence, her longing to belong, when her family fail to protect and nurture her. To transform/transcend the specific adverse social conditions of T&T we must first acknowledge rather than deny the plantation’s legacy of brutality, which persists in the sometimes very cruel way people deal which each other. Under the veneer of modernity and globalization this brutality continues unchallenged –children are still viewed as potential labor and objects not as vulnerable emerging people thus, robbing them of their childhood and the emotional development necessary for them to become complete caring adults.

Various global and local influences have accelerated the meltdown of postmodern Trini society, and I believe that we can transcend/transform our condition by revisiting/revisioning some of our Creole cultural expressions and rituals, many of which focus on healing and community. This is the way forward for us in our unique historically framed reality. We can’t solve our very basic problems by distracting ourselves with the trinkets of globalization –social media, global mass culture, pretending once again that what happened over the last 300 years in T&T didn’t happen. Recognizing the oppression and suffering we’ve inflicted by following the plantation model is a vital first step, and Madinah Girl recognizes all this and throws it in your face. It demands that readers, especially here in T&T and the Caribbean, take responsibility for their humanity, or lack of it and by confronting our daily horrors we can then move forward.

TFR:

And what does it take for the human spirit to transform/transcend adverse social conditions?

Levi:

I think again it’s freedom, you know?

TFR:

What does that line mean: “Men like to use women and treat them like metal”?

Levi:

You know metal is something that is very hard. It’s a saying in the Caribbean. Metal is something you can hit on the ground many times. It can bend but it can’t hurt like a human body, it’s an object. So it means that men like to use Drupatee like an object. Something that can’t feel. So women aren’t supposed to feel anything when they’re abused.

TFR:

Madinah Girl seems at once intensely autobiographical—sometimes excruciatingly so—and yet utterly NOT an autobiography of the author, Anna Levi. How do you talk about that issue of muddling the line between autobiography and autobiographical writing?

Levi:

Art comes from life, is a part of life, can inform life but shouldn’t be confused with life. Madinah Girl began from a store of life stories I kept telling my husband. When he got fed up with hearing them for the nth time, he suggested I start writing them, in the same voice as I told them. Obviously much of the raw material is autobiographical, but my intention never was to write an autobiography but by presenting a series of fragments to make some sense of my own fragmented childhood and adolescence and a period of recent Trini socio-cultural history which hasn’t really been written about from the bottom up.

TFR:

What are you working on now, and what can you tell us about the scope, the focus, the stylistic issues?

Levi:

I’m reading for a Masters in Fine Arts in Creative Writing at the University of the West Indies. I’m working on my second novel, “Nowherians”. It’s about the life, living condition, and treatment of children who were raised with informal fostercare parents/families and even orphans in Trinidad and Tobago. Most of my materials are from experience… but to give me a boost, I talk to vagrants, drug addicts, ex-convicts, incurably insane people, happy children, sad children, elderly impoverished people, criminals, sex workers, immigrants, and even religious spiritual leaders/healers. In writing, I love, respect and appreciate the dialect Trinidadian English creole and all other dialects from the Caribbean …. in fact the world. I like to write with visibility. The first chapter of “Nowherians” was adapted into film by film students at the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad, under the supervision of their directing lecturer, Yao Ramesar.

TFR:

Before we wrap up, can you talk about your interaction with the filmmakers? What did you see? How was that set up? What kind of versions of your writing did they produce?

Levi:

So, there’s the film department at UWI, and my work was selected, so they took a chapter from “Nowherians”, and the students had to read and take any part and adapt it. Some students liked the landscape, right, so they did a silent film on the landscape. Some of them loved the dialogue and did the dialogue. Some of them liked different parts of the book. They changed it up and adapted it, but it’s very connected to the book itself. I spoke to them before they made their films and they told me what were their plans. It was a great attempt because some of them didn’t even have dialogue in their film, they had just a landscape, just a young boy who grew up. He was an orphan and he grew up, and he’s walking through the place that he knew when he was young, like an old broken wooden house where it had fallen, with his pets and just some music in the background showing his emotion. I’m really loyal to “Nowhereians” and really dedicated to finishing it.

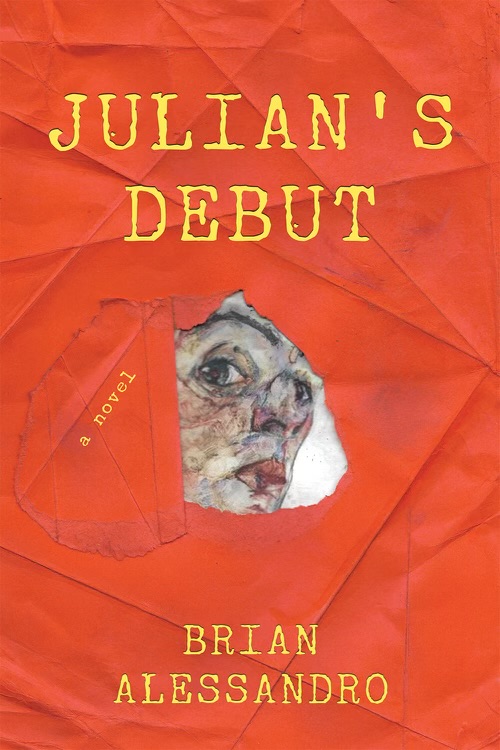

Julian’s Debut

Julian’s Debut

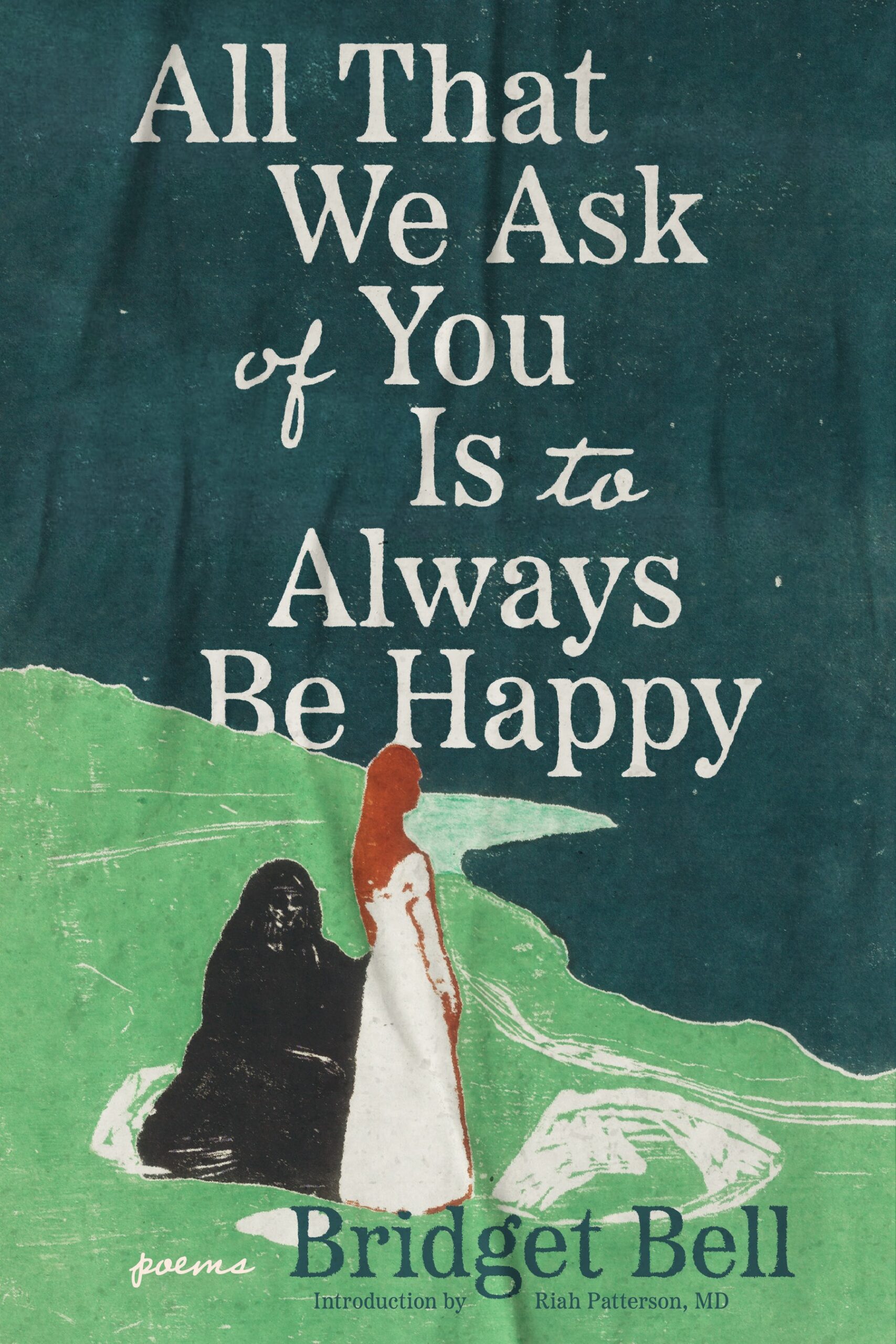

Bridget Bell’s debut poetry collection—All That We Ask of You Is to Always Be Happy (CavanKerry, 2025)—explores maternal mental health. She is the recipient of a North Carolina Arts Council Artist Support Grant and teaches composition and literature at Durham Technical Community College. Additionally, she pours points at Ponysaurus Brewery in Durham, NC and proofreads for Four Way Books, a literary press based in Manhattan. Originally from Toledo, Ohio, she is a graduate of Sarah Lawrence’s MFA program in creative writing. You can find her online at

Bridget Bell’s debut poetry collection—All That We Ask of You Is to Always Be Happy (CavanKerry, 2025)—explores maternal mental health. She is the recipient of a North Carolina Arts Council Artist Support Grant and teaches composition and literature at Durham Technical Community College. Additionally, she pours points at Ponysaurus Brewery in Durham, NC and proofreads for Four Way Books, a literary press based in Manhattan. Originally from Toledo, Ohio, she is a graduate of Sarah Lawrence’s MFA program in creative writing. You can find her online at

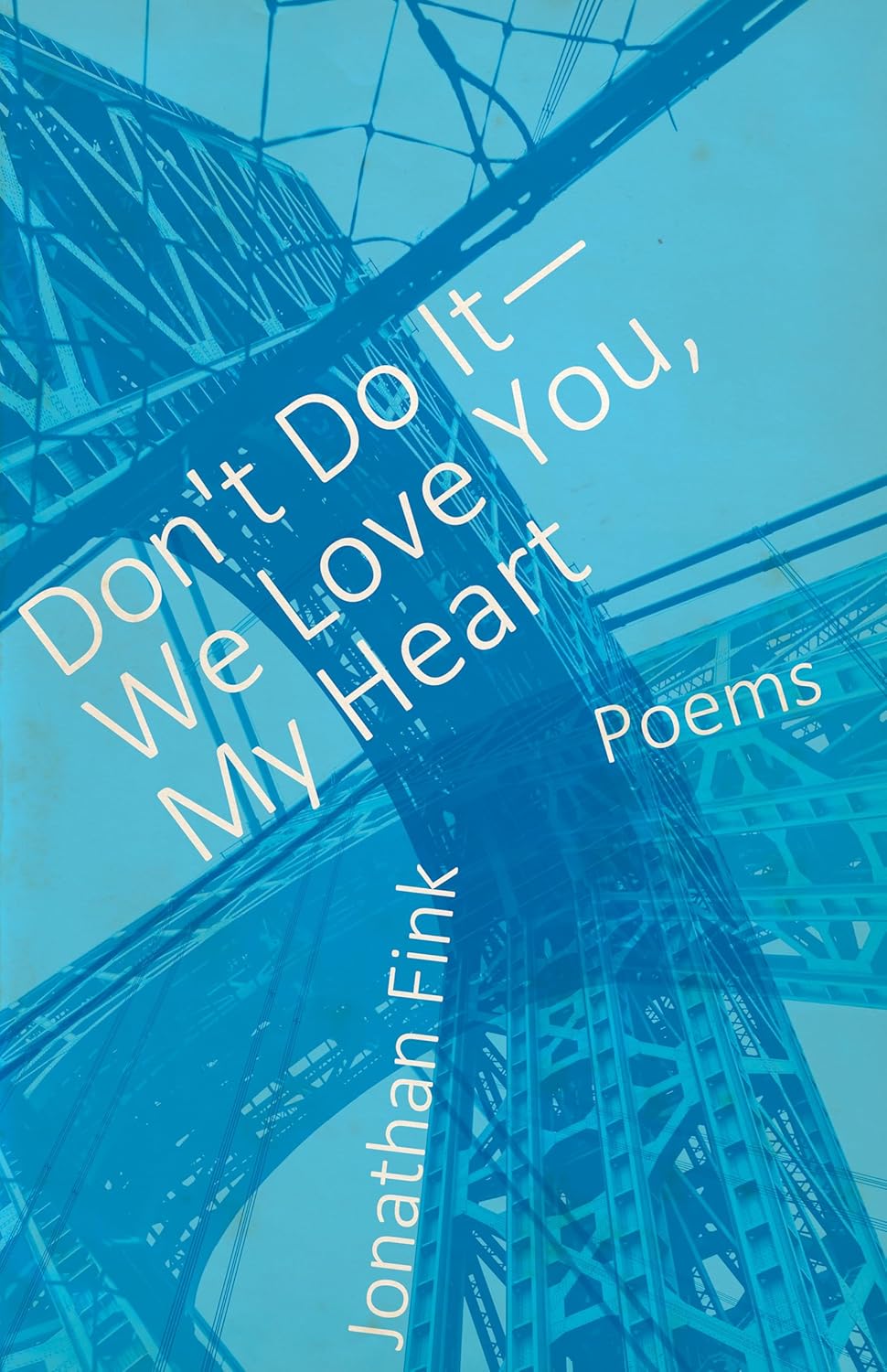

Jonathan Fink is Professor and Coordinator of Creative Writing at University of West Florida. His most recent book of poetry is Don’t Do It—We Love You, My Heart (Dzanc, 2025). He has also received the Editors’ Prize in Poetry from The Missouri Review, the McGinnis-Ritchie Prize for Nonfiction/Essay from Southwest Review, the Porter Fleming Award in Poetry, and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Joshua Tree National Park, the Florida Division of Cultural Affairs, and Emory University, among other institutions.

Jonathan Fink is Professor and Coordinator of Creative Writing at University of West Florida. His most recent book of poetry is Don’t Do It—We Love You, My Heart (Dzanc, 2025). He has also received the Editors’ Prize in Poetry from The Missouri Review, the McGinnis-Ritchie Prize for Nonfiction/Essay from Southwest Review, the Porter Fleming Award in Poetry, and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Joshua Tree National Park, the Florida Division of Cultural Affairs, and Emory University, among other institutions.

Amy Stuber has published fiction in New England Review, Missouri Review, Copper Nickel, and elsewhere. She’s a flash editor at Split Lip Magazine. Her debut collection, SAD GROWNUPS, comes out October 8 from Stillhouse Press.

Amy Stuber has published fiction in New England Review, Missouri Review, Copper Nickel, and elsewhere. She’s a flash editor at Split Lip Magazine. Her debut collection, SAD GROWNUPS, comes out October 8 from Stillhouse Press.

Pat Spears is the author of three novels and numerous short stories. Her second novel, It’s Not Like I Knew Her, won the bronze medal for Foreword Review’s Book of the Year in LGBTQ Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in numerous journals, including North American Review, Sinister Wisdom, Appalachian Heritage, Common Lives, Lesbian Lives, and Seven Hills Review, and anthologies including Law and Disorder (Main Street Rag), Bridges and Borders (Jane’s Stories Press), Saints and Sinners: New Fiction from the Festival 2012, and Walking the Edge: A Southern Gothic Anthology (Twisted Road Publications). She is a sixth generation Floridian and lives in Tallahassee, Florida with her partner, two dogs, and one rabbit.

Pat Spears is the author of three novels and numerous short stories. Her second novel, It’s Not Like I Knew Her, won the bronze medal for Foreword Review’s Book of the Year in LGBTQ Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in numerous journals, including North American Review, Sinister Wisdom, Appalachian Heritage, Common Lives, Lesbian Lives, and Seven Hills Review, and anthologies including Law and Disorder (Main Street Rag), Bridges and Borders (Jane’s Stories Press), Saints and Sinners: New Fiction from the Festival 2012, and Walking the Edge: A Southern Gothic Anthology (Twisted Road Publications). She is a sixth generation Floridian and lives in Tallahassee, Florida with her partner, two dogs, and one rabbit. Carolyn Forché is the author of five books of poetry, most recently In the Lateness of the World(Penguin Press, 2020), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and also Blue Hour (2004), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, The Angel of History(1995), winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Award, The Country Between Us(1982), winner of the Lamont Prize of the Academy of American Poets, and Gathering the Tribes (1976), winner of the Yale Series of Young Poets Prize.

Carolyn Forché is the author of five books of poetry, most recently In the Lateness of the World(Penguin Press, 2020), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and also Blue Hour (2004), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, The Angel of History(1995), winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Award, The Country Between Us(1982), winner of the Lamont Prize of the Academy of American Poets, and Gathering the Tribes (1976), winner of the Yale Series of Young Poets Prize. Hurricane Season is a noir thriller about fighting and addiction, prison and drugs; but more than that, it is a love story set in the carnage of an America wrecked by inequality.

Hurricane Season is a noir thriller about fighting and addiction, prison and drugs; but more than that, it is a love story set in the carnage of an America wrecked by inequality. Mark Powell is the author of seven novels, including Lioness, Small Treasons–a SIBA Okra Pick, and a Southern Living Best Book of the Year–and Hurricane Season. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Breadloaf and Sewanee Writers’ Conferences, and twice from the Fulbright Foundation to Slovakia and Romania. In 2009, he received the Chaffin Award for contributions to Appalachian literature. He has written about Southern culture and music for the Oxford American, the war in Ukraine for The Daily Beast, and his dog for Garden & Gun. He holds degrees from the Citadel, the University of South Carolina, and Yale Divinity School, and directs the creative writing program at Appalachian State University.

Mark Powell is the author of seven novels, including Lioness, Small Treasons–a SIBA Okra Pick, and a Southern Living Best Book of the Year–and Hurricane Season. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Breadloaf and Sewanee Writers’ Conferences, and twice from the Fulbright Foundation to Slovakia and Romania. In 2009, he received the Chaffin Award for contributions to Appalachian literature. He has written about Southern culture and music for the Oxford American, the war in Ukraine for The Daily Beast, and his dog for Garden & Gun. He holds degrees from the Citadel, the University of South Carolina, and Yale Divinity School, and directs the creative writing program at Appalachian State University.

![Cover of Danez Smith's [insert] boy](https://cah.ucf.edu/floridareview/wp-content/uploads/sites/34/2018/09/cover-of-Danez-Smiths-Insert-Boy-257x300.jpg)