In the ninth grade my face got all trucked up in a car accident. The next year my high school let me be a judge at their annual chili cook-off. Ever since, on the eve of the season’s first freeze, I make a big pot, the beginning of two months of competition. I find the process soothing. My recipe changes from year to year. I’ve never written it down and being prone to heavy drink, I invariably forget something. My maxim is to keep it simple. This is Omaha. Don’t need to be showing up at the American Legion Hall with braised short-rib chili.

The onset of winter around here is a curious thing. There’s excitement in the air despite everyone knowing that in a month we’ll all be begging for spring. My chili season routine goes as such: on Wednesday I hit the grocery store. Thursday, I dice everything up: onions, peppers, garlic, and tomatoes. Fix a drink. Brown the meat. Refill my drink. Add everything to the stock pot, stir it real good, and let it rest in the fridge overnight. All day Friday I cook it down, adding beer/coffee/broth as needed. On Saturday I bring it to whatever cook-off is happening. Sundays I’m hungover. Monday and Tuesday are pretty inconsequential.

I’ll be up front about it, one of the buddies I was in the car wreck with didn’t make it out. He was sixteen, two years older than me, and he was driving. The other buddy, Tim Slobowski, was my age. We were on a rural stretch of road, what we called out north. Slobowski was ejected from the car. His brain went without oxygen for forty-five minutes, and he spent the next six weeks in a coma. After that they moved him to the Madonna House Rehab Hospital, where he doesn’t know who he is or where he’s at. I used to visit, but it’s been a while.

People at the Hy-Vee see what’s in my cart and give me looks of approval, the man making midweek chili. Such jaunt in my step. My go-to protein is a mixture of Italian sausage and ground beef (1:3). In the past I’ve done some wild experimentation, depending on how frisky I’m feeling. Have used everything from elk to pulled pork to brisket. Where I draw the line is chicken, white chili, which I won’t do. In a few weeks my hunting buddies will start getting last year’s venison out of their deep freezes and I’ll make a few batches with that, but until then, I’ll keep it simple. Italian sausage and ground beef.

As I exit the store, the Salvation Army bell ringer is going at it like he’s John Bonham. I wasn’t planning on donating (no idea where the money goes), but I admire his tenacity. I stop the cart and fish around in my pocket. The drummer does a triplet. He’s wearing fingerless leather gloves. The bell is vise-gripped to a hi-hat stand. He goes at it like a trap set. I bend down with my dollar. He looks at me. We recognize each other. He grins in a way that says he knows it’s me, and yeah dude, it’s him: my old friend, Doogie. He stops mid-song, looks in my cart. “Whoa motherfucker,” he says. “You making chili?”

Aside from family, I’ve known Doogie longer than anyone else. His stepdad coached our little-league team, this mustached dude who’d pitched collegiately and was obsessed with bunting. Later, Doogie and I did drugs and played in punk bands together, which is when he dropped the name William and took on Doogie.

“Doogie,” I say. “What the fuck man, I thought you were in Denver.”

“Made it nine months out there, but I’m back. Been so for a few weeks.”

I nod at the tithing bell. “The hell is this?”

“The fuck’s it look like? Denver’s not cheap.” He lowers his voice. “You still…”

“Gave it up,” I say. “Coming on two years.”

“Congrats. That’s why I moved. Worked for a while too, but you know that junk is everywhere.” He puts a hand on the case of beer in my cart. “Haven’t kicked this, I see.”

“Technically that’s for the chili.”

“Fuckin A.”

“Hey man,” I say. “Is this what it looks like?”

“Not really.” He looks around. “Actually, maybe.”

Ninety percent of my friends from his days are gone. Some left to reinvent themselves and some passed away and some got married, had kids. I spent a decade moving around. Whenever things came close to falling in place, something came up. Emergency dental surgery or a bad breakup or x, y, and z. I pull a twenty from my billfold. Doogie pockets it on the sly and gives the bell a thwack, thanks me for being a good friend.

In the three years I’ve been back in Omaha, I’ve entered forty chili cook-offs. Placed in the top three at thirty of them, fifteen of which I won. I know it’s a weird hobby, but if my biggest proclivity is an obsession with making chili, I consider myself healthy. It’s Thursday morning and my stomach is weightless in anticipation. Been since March that I last made a batch. I hone the chef’s knife, ready the cutting board. The tips of my fingers get prickly. I start my audiobook: Stephen Covey’s The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. It’s been my soundtrack for the last two chili-cooking seasons. Over the next couple months I’ll take it to the house three, maybe four times. Put it away for the year, recharged.

I am in control of what defines me. Covey hammers that. Don’t have to be defined by my past. Humans have the power to choose. That’s why I moved away. Fuckers all saw me as the dude that had been in the car accident. For many years I was erratic. Covey helped me regain control. It’s like he says, so much about who we are is determined in the split seconds between stimulus and response. And never forget that you have the power to choose.

The baseball team that Doogie and I played for—the Omaha Tornadoes—the summer after sixth grade we made a run at the Little League World Series, the event that’s televised on ESPN. All season we used the thought of ourselves on TV as motivation. A communal fantasy that grew out of control. We made it to the final round of regionals in Wichita, KS. One more and we were in. We could practically see ourselves in the nation’s living rooms, dominating with small ball. The hope for a better tomorrow. We ended up losing in the last inning of the championship game and shortly thereafter found out that we hadn’t even been competing in the tournament that climaxes on ESPN. We’d been in some rinky-dink knockoff version, lied to by our parents and Doogie’s stepdad, who knew we’d be motivated by TV. The whole experience ruined baseball for me.

I love waking up on chili cook-down Friday. Last night it was hard to fall asleep, similar to the last day of school as a kid, a memory I barely remember, but it was embryonic, the windows open to perfect weather. I put the pot on the range and slowly bring it to a boil, stirring in cumin, cayenne, and paprika. Half a Hershey bar. A quarter cup of cold brew. Couple tablespoons of Mexican coke. Last year I fucked around with soda syrup as the sweetener. It was close to what I wanted, but the line to toe was thin and it made me feel like I was trying to be something I’m not, unbearably pretentious.

All told I spent a decade away from Omaha. Went from Tampa to Lake Charles, Asheville and Pensacola—once for love, once for a bar, and the others for no real reason, reinventing who I was every few years. One of the things I consistently missed were the chili cook-offs, nothing like they are in the heartland. To the credit of Lake Charles, they had a bunch of well-attended gumbo cook-offs around Mardi Gras, but I only like that stuff in extreme moderation. At the last one I attended I was eating a bowl in front of the guy that made it—duck and andouille—and on my second spoonful I bit square into a piece of buckshot. I pulled the BB from my mouth and the guy started laughing like a goddamn maniac. I didn’t think it was funny, though. That incisor is still chipped.

I bring the chili to a hard boil and kill the heat. Add in some bone broth and work it to a simmer. I can’t stress enough the importance of a quality stock pot. I’ve got a top-end chef’s knife as well, German forged steel. Those Japanese brands look sweet, but I’ve heard they require a ton of maintenance. Even though it’s been years since my last relationship fell apart, I still fantasize about the gift registry she and I put together, sorry we didn’t stay together long enough to see it through. The kitchen we would’ve had.

The cook-off they let me judge after my accident was our high-school’s big annual fundraiser, climax of the blue-and-white weekend. The three judges are usually big-time alumni. It’s considered an honor. That’s what my mom kept harping on after I was invited. I was hesitant, but she insisted. And she was right. Whole crowd gave me a standing-o when I took my place. I was seated next to a famous movie director, class of ‘79. He’d just finished filming something with Matt Damon. It’d been the talk of our high school. The emcee put two flights of chili in front of me. The director noticed my shaking hands, leaned in and said that Matt Damon had found my story very compelling. By the time I reached the next taster, I’d settled down. I took a bite and pretended to gag, real cartoon-like. At that moment everyone in the audience knew I’d be fine. They beamed up at me, proud of the way they’d rallied around the poor kid. Helped him overcome adversity. Many years later I drunkenly tried getting in touch with the director to see if he could help me out. His people said he was on location in Hawaii, and that if he didn’t get back to me in a few months, to follow up. But he didn’t and neither did I. The whole thing was stupid. What was I expecting, him to cast me in some fucking Jason Bourne movie?

After three hours of simmering, I give the chili my inaugural taste. Swish it around like a wine snob. As anticipated, there’s something missing. Always happens with the season’s first batch. Last weekend I emptied my pantry, which I do at the beginning of every October, keep the spices and toss the rest—hard to innovate while constipated with yesterday’s shortcomings. The pitfall is that this chili needs something I don’t have. It’s no problem, though. Hy-Vee is close and maybe I’ll get to see Doogie again. Been thinking a lot about how I got off the path we were on and he didn’t. The emptiness he must be feeling. I’ve been there.

After the dust from the car wreck settled my parents hired an attorney. The hairpin turn we wrecked at wasn’t labeled. No guard rail either. Everyone’s assumption was that we’d been drinking, but we hadn’t been. My buddies and I were just out for a joy ride, Nebraska in early April, looking for sandhill cranes. When we launched off the road my stomach shot through my throat. Time elongated into milliseconds I could see and touch. There wasn’t any calm or clarity, or whatever people tell you they feel in the moments before death. It’s all a lie. I only felt terror and all I wanted was to be alive. Then we crashed in a soy field and started rolling. My attorney was a real bulldog. The county was on the hook. My folks put my settlement money into a trust. Every month until I turn forty I get two grand. It’s been a blessing and a curse.

This time when I approach the entrance to the grocery store there’s no Salvation Army bell ringer. Honestly, I’m disappointed. The vision of Doogie’s face has been in the back of my mind. How worn down it looked, like an old catcher’s mitt. I shouldn’t have left him in the lurch all those years ago when I up and moved away, cutting ties with who I was. From eighteen to twenty-five, he and I travelled the country pursuing punk-rock fantasies. Taught a bunch of shit-hole bars a thing or two about having a good time. Made caricatures of ourselves and called it profound. Swore we were pursuing the life we wanted, fast and hard. Paycheck to paycheck. Then the pixie dust wore off and I moved away without saying much. Just needed a change.

I meander through the grocery store. Grab some high-end bone broth, a couple ghost peppers, another can of tomato paste. An orange (for the zest). When I’m leaving the store I hear someone wailing on the bell. I’m thrilled. Can barely contain myself as I turn toward him. He’s wearing a necktie as a headband, Judas Priest long sleeve under the Salvation Army vest. Drums a line of blast beats.

“Doogie!”

“My dude. Back again.”

“Needed a few things for my chili,” I say. “How’s it going, man?”

“Nice as shit out today. I’ve been trying to figure out if there’s any correlation between weather and generosity. Far as I can tell, it’s random.” He swings the donation kettle back and forth. “Bunch of fucking cheapskates.”

“Dude, you know what I was thinking about after I saw you the other day? Remember that year we almost went to the Little League World Series?”

“Twenty-three years ago,” he says. “It’s like they say, time flies when you’re having fun.”

“You want to ditch this and come over for some chili?”

He fidgets around. “Got any of that beer left?”

“Eighteen at least.”

He removes his vest and says, “I’ll hop in with you.”

The neighborhoods we used to live in are nice now, full of street tacos and cocktail bars. Our drug house was gutted and turned into a vinyl-listening library, $79 a month, one of the best record collections in the Midwest. When we lived there, we were constantly having to scrape together extra money to get the utilities turned back on. Place had revolving doors. My room was on the top floor. Doogie’s drum set was in the basement. Despite sound proofing it with egg cartons and junked mattresses, I heard every beat of his practices, and he was always at it. Ever since I’ve needed a box fan to sleep, that dump was so loud all the time. Makes me glad it’s something pretentious now.

Immediately upon entering my house, Doogie says, “Good fuck. It smells fantastic.” He checks out my trinkets. I’m a collector of several things. Bobbleheads and postcards and koozies, most extensively. When I started accumulating them, I stopped getting tattoos. Win-win. I’ve got koozies from all over the country. Some from places Doogie and I went together, like the bar in the lobby of the heart-shaped hot-tub motel in Jackson, MS. First time we tried meth.

“You really hate having a warm beer and a cold hand,” he says, looking at all of them. “I’ll give you that much.”

“See the one from Slims in Raleigh?” I say. “That place was insane.”

“Oh man, I still feel bad for that guy. Dude who put us up. He didn’t deserve that from us.”

“Yeah,” I say. “I forgot about that. Certainly not my proudest moment, but he had money and was an asshole to begin with.”

I get us a couple cans of beer. The chili is simmering on the range. I prepare the fixins: a bowl of Fritos, Crystal and Tabasco hot sauce, fine-shredded cheddar. In Nebraska it’s customary to serve cinnamon rolls with chili—they get us started on it in elementary school—but I don’t play by those rules. Fuck that. I put the chili in front of us, normal fixins. Before taking his first bite, Doogie wafts it under his nose. “What’s that I detect,” he says, “nutmeg?”

“Maybe.”

He wolfs the bowl down without another word. I’d go so far as to say I knocked it out of the park. Again.

“Well,” he says. “Pretty decent.”

“Pretty decent? Variations of this recipe are going to win a ton of cook-offs.”

“I’m no chef de cuisine, but it seems like you over handled it a bit. Folks want a robust, simple chili. This tastes like it doesn’t know what it wants to be. You know what I mean? It lacks an identity.”

“Yeah?”

“The fuck do I know, though, I’m a Hormel man.”

“Get out of here with that. Seriously?”

“You like what you like.”

The guy’s got dirt under his fingernails, sniffles a lot. Almost forty-years old and still rocking a Judas Priest shirt. He’s as lost as I once was, an addict. I shouldn’t fault him for the Hormel comment. He doesn’t know any better. I grab us another couple beers. “Listen,” I tell him. “I think I’ve got something that could help you out.”

“Less cumin in the chili?”

“Funny,” I say. “I’m trying to be serious for a second.”

I keep several copies of Seven Habits around the house for this very occasion, a friend in need. I hand him the multi-disc audio edition. He holds it like a problem child with the body of Christ. “You might think it’s bullshit,” I say. “But it worked for me.”

“Worked like how?”

“Helped me get in control of everything. I had a victim’s mentality for pretty much my whole life. Bad things kept happening to me because bad things always happen to me. You know what I mean? That type of philosophical outlook.”

“Fuckin A,” he says.

“Friend to friend, I’ve been where you’re at.”

“Look, man,” he says. “I thought we were here to eat chili. If I wanted to be proselytized, there’s any number of people more qualified than you that I could’ve gone to. No offense.”

“Trust me, I was the same way. This shit, it can take a load off.”

“That’s not the point.”

“What is the point?”

“I don’t want unsolicited life advice. Especially from someone like you.”

He’s the same way I was, hardheaded. Covey helped me realize that.

“Just take it,” I say. “Do whatever you want with it. Doesn’t matter to me. But take it, just in case.”

—

I won the first two cook-offs of the season. Spent three weeks honing my recipe and then boom, I took O’Leavers on the first Saturday in November—$100 bar tab—and The Winchester the following weekend, where this biker in his seventies finished second. By the time they announced the results the biker was damn near incoherent, prison-sleeved and in the throes of what appeared to be a psychedelic trip. For winning that one I got a toilet trophy and fifty bucks. The biker got a bottle of blackberry brandy. He had a tough time figuring out what it was.

I am a well-oiled machine. My house smells delicious all the time. If they made a chili-scented candle, I’d be the target demographic.

I kicked the shit out of The Sydney’s cook-off. They never stood a chance. Two different yahoos had chickpeas in their chili. To them I said, “Why does the sexual deviant like your chili so much?”

Huh?

“Because the chickpeas.”

And I rode off into the sunset, gift card in my pocket.

Bribery and ass kissing are rampant in the competitive chili scene. It’s always better to have a panel of judges than audience voting. No telling whose team folks are on. Another pro tip: invest in a decent crockpot. Nothing too expensive, but nothing too shitty. People judge at either end. What can I say, they eat with their eyes. And if the cook-off benefits charity, do a little research first. Or just avoid them altogether. They bring out some serious amateurs. The ones at old-school bars are where it’s at.

Oh, and don’t show up with bean-less chili. Whenever someone does, we talk shit behind their backs.

I open the year six for eight. Lost two to charity, but what the hell, they were for good causes. Not like it’s my fault that the parents of the Kingswood Athletic Association have unsophisticated palettes. Keep your crown, you well-done assholes. And never again lie about how the baseball season could end. None of those cook-offs matter anyways. My green jacket, the creme de la creme, is this weekend at the Homy Inn. Culmination of the season. The place is an institution, beloved by the types of lawyers/doctors/rich folk who give big at my high school’s annual fundraiser. While most cook-offs get between ten and twenty entrants, the Homy will have upwards of fifty, judged in stages. $500 on the line. I’ve never won. Last year I took third. For it I’m breaking out the big guns. I started my prep work a week ago. Went and bought a pork butt that I cut into inch-thick strips. They’ve been curing in crab boil and canning salt in the fridge, a cup of sugar. I’ll smoke the slabs into tasso a few weeks from now. What I’m after in the meantime are the shoulder blades. Left a good amount of meat on them. They’ve been in the curing solution. I’ll add them to the chili at the very beginning, let them season everything. All told it’s a two-week process.

They ought to crown me champion now, Friday afternoon. This batch is incredible. The pork bones worked wonders. After a few hours of simmering, I was able to shred the meat right off. It’s got a feathery texture, packed with flavor. Perfect complement to the Italian sausage and ground sirloin. I should’ve been writing down my recipes all along. For posterity. Maybe open up a chili parlor someday. Write a cookbook and have Matt Damon blurb it. At the very least, I’d be able to see what the changes say about who I became, no longer the brooding dude on the verge of an episode. I am the chili master now.

On Homy Inn Saturday I wake up at the crack of the sparrow. Begin the day with thirty minutes of yoga on YouTube. Follow that up with fifteen minutes of mindfulness, guided by YouTube. Then I take a hot shower. After the shower I pull the chili from the fridge and put it on the range, slowly bring it to temperature. I eat a bowl straight up, no garnishes. Phenomenal stuff.

The cook-off starts at two. I show up at one, bring it in the front door. The bartender takes it to the back, where they’ll transfer it to a quarter tray, to be labeled and served from steam tables. The right way to do things. Total anonymity. I settle into the bar, have a beer and a shot. My chili might be superfluous, but when it comes to drinking, I’m a meat and potatoes guy. More and more people arrive with chili. Some look like straight-up yokels. I rule them out. The rough looking ones are the ones I’m worried about. That old-timer with the neck tattoo, for example, he ought to get a first-round bye. Respect for the lifers. The bar’s capacity is a tight 175. Today they’ll reach that. The bartender brings me another beer and addresses me by name, asks how my chili turned out.

“Pretty good,” I say.

I’m tempted to tell him how awesome it is, but I’ve overheard a bunch of contestants running their mouths and in this arena I want to be the strong and silent type. As Covey would say, the choice is mine.

Forty chilis have been entered. The bar is wall-to-wall. A couple sore-thumb tourists pump money into the claw machine, nothing in it but a big pink dildo. What a dive, they laugh. Folks always act surprised when they realize said dildo is greased, which should probably be a given. The Homy has been putting this on for over twenty years. They’ve got it down pat. Chilis have been separated into groups of ten. The first round will be judged by the audience. Every attendee has been assigned a flight and given a scorecard. Top three from each will advance.

Minutes before it’s about to start, the front door swings open. Standing in the gust of frigid air is my old friend Doogie. He’s carrying a greasy crockpot, balances it against his stomach with one hand. Fist bumps the door guy with the other, who then hustles it to the back. Doogie catches sight of me. I raise my glass. He gives me a stern-faced thumbs up, goes and registers with the event coordinator—the octogenarian proprietress who takes absolutely no shit from anyone. For the past fifteen years she’s made a pot of chili for people to eat during Monday Night Football and for my two cents, it’s pretty good. I expect her to give Doogie a hard time, but she doesn’t. In fact, they seem to have a rapport. He comes to my side and orders a drink and I say to him, “Didn’t know you were into making chili. Which number is yours?”

“You know it’s against the rules for me to divulge that information prior to the completion of first-round voting. I may be a fuck up, but I’m no cheater.”

“What do you say we get a little side bet going?”

“I don’t approach making chili with a results-based mindset. I trust what I cooked. For me, the joy is in the process.”

“You listened to the book,” I say. “Awesome, man.”

It’s vintage Covey. Always act with the end in mind.

“The hell I did,” he says. “What’s the bet? I’ll take your action all day.”

“Forget about it. You’re right about being process based. It’s all in good fun. I’m glad to see you’re doing well.”

“Five-hundred,” he says.

“You’re good for that?”

“Here he goes again, Mr. Shit-Together.”

He does look healthier. Not as strung out.

“Fine,” I say. “Five-hundred it is.”

I’ll take this dickhead’s money. Kickstart him into helping himself.

“I don’t even care for chili,” he says, “but having tasted yours, I know I can beat it. Someone has to put you in your place.”

“Yeah?”

“See you at the finish line, asshole.”

I’m starting to remember why we had a falling out. Dude’s kind of a prick. Only reason he started at second on our little-league team was because his stepdad was the coach, the mustached man who orchestrated the whole ESPN lie. I’m sorry to say it, but his stepson is about to lose five-hundred bucks.

Will I make him pay?

Goddamn right.

The emcee starts the event. First round will take an hour. It’s warm in the bar, spirited. These things aren’t really about winning. They’re about Midwestern camaraderie. The shared misery of another winter, born to die in Nebraska. This bar regular I’m friendly with, Rat-faced Johnny, plays Motörhead from the jukebox. He knows I’m a fan. “Here’s to pissing in the wind and shitting where you eat,” he says. Motörhead ends and Iron Maiden comes on. Rat-faced Johnny does it again.

I sample all ten chilis I’ve been assigned. Have a sip of Aperol spritz between each. Don’t care if the drink looks ostentatious, it’s a great way to cleanse the palette. Three of the chilis are decent. Four are palatable. And three are downright lousy. If they’re any indication as to how these people eat at home, I feel sorry for them. No doubt I’ll advance to the next round.

Doogie shuffles to my side and says, “I know which one is yours. Heavy on the cumin again.”

Before I can retort, the bartender cuts the jukebox—Rat-faced Johnny is not amused, middle of his favorite Black Sabbath song—but they’re ready to announce the first-round results.

“You think you made it through?” I ask Doogie.

“At this point,” he says, “it’s outside my control and therefore, I am unconcerned.”

Another of Covey’s tenets. Even if he’s mocking it, at least he listened.

“By the way,” I say. “That was a bullshit move your stepdad pulled. Convincing us we were going to the Little League World Series.”

“You’re telling me,” he says. “I had to live with the fucker.”

The emcee fumbles around with the PA system. People are mirthful. Days are getting longer. We’re past the peak of winter. In no particular order, the emcee calls the numbers of those that have advanced into the finals. Of course I am among them. Doogie stays calm throughout. “You make it through?” I ask.

“Man,” he says. “Why’d you have to bring up my stepdad? I’m not trying to think about that guy right now. Fucking ruined my day. That’s a bullshit move.”

The last thing I expected was tenderness. “You’ve been a prick all afternoon,” I say. “I was just giving it back.”

“I know why you’re obsessed with this chili cook-off bullshit. It’s because they let you judge that one in high school after the accident went down. Got me thinking, man, when’s the last time you’ve been out to see Slobowski?”

He knows not to go there. I shake my head.

“Just a question,” he says. “I’m genuinely curious.”

“You know the answer.”

It’s not a conversation I care to have with anyone, let alone an old junky buddy.

“Anyways,” he says, eagle eyeing the barroom. “I’ve got to go catch up with some folks. Good luck with the next round.”

The bartender kicks the jukebox back on. Rat-faced Johnny raises hell, says it skipped his songs and ate the remaining credits. Now it’s playing some bullshit Aerosmith song and everybody in the state of Nebraska knows he hates them. Johnny’s nickname isn’t flattering, but it sure does fit. The bartender tells him to settle down. Not like the jukebox is going anywhere.

The judges take their places at the head table. Two of them I recognize, the chef from the Boiler Room and this stout guy named Dario, owner of Dario’s. Best steak frites in town. The third judge I’ve never seen before, some lady who teaches culinary arts at the community college. Over the years I’ve learned not to overthink what the judges might be thinking. There’s nothing their reactions can tell me about chili that I don’t already know. I lean back and enjoy my spritz. Peace be the journey. I order a refill on Doogie’s tab.

The judges head to the backroom to deliberate. I sample all ten of the finalists. Seven are solid. Sometimes I get too cocky and underestimate my competition. Wouldn’t be the first time hubris has fucked me. Three of them even, I wouldn’t be ashamed to lose to. One seems to have hit exactly what it’s going for. Perfect combination of heat and flavor. This brilliant texture to it. Oh wait, it’s mine.

Nice.

The judges emerge with their results. The emcee has an envelope in hand. He delivers a little hoopla. Thanks us for being here. Says they couldn’t have asked for a more qualified panel of judges. And what a way to kick off the homestretch to Spring. My nerves ratchet up, suspended in the in-between while this guy finishes his spiel.

No matter the outcome, I know in my heart of hearts that I am a winner.

I advance into the top five. Those that have been eliminated go and collect their consolation ribbons. The emcee whittles out two more. I’m in the top three. Soon they’ll be etching my name on the plaque, forever part of something bigger than myself. Doogie is stone-faced. I have no idea if his chili is still alive.

Just name the goddamn winner already.

And then they do.

William “Doogie” Donahue.

The audience gives it up for him.

Son of a bitch.

He tries to accept it stoically, but has a teenager’s sheepishness when he takes the trophy. Looks out into the crowd and raises his arms. I’m pissed off, but oh well. I’ve got to admit, his chili, #6 of the finalists, was good. Nice and hearty. Midwestern. I put my hands together for him, my old friend.

There’s always next year and the next year and the one after that. Adapt and survive. Maybe I’ll open a chili parlor when my two-grand allowance runs out, call it Slobowski’s. I’ll go out to the Madonna House to see him soon. It’d be nice to catch up with his mother as well. I know she was bummed when I quit visiting, disappeared in pursuit of something I never found. Didn’t even bother returning her calls. But I’m back in control now, helping old friends win chili cook-offs. Some much-needed meaning in Doogie’s life.

The bar settles down. Empties by about half. It’s 4:30 now. In an hour it’ll be dark. For finishing second I got a $200 tab, which I’m putting to good use. Gave rat-faced Johnny permission to drink on it until it’s gone. Would’ve thought he won the lottery when I told him.

“It was a well-fought battle.” Doogie comes up and shakes my hand.

“You showed me,” I say. “I apologize. Got ahead of myself.” It’s important that I be the bigger man. “You do Venmo?”

“Cash only, bucko.”

He follows me to the ATM. I hand him the five hundred and say, “I guess we’ll see each other when we see each other. Until then, be well.”

“You know what my chili was?”

“What?”

“Just Hormel that I doctored up a little bit, you self-righteous son of a bitch.”

“Motherfucker.”

He walks away—middle finger up—out into the dregs of winter, a champion.

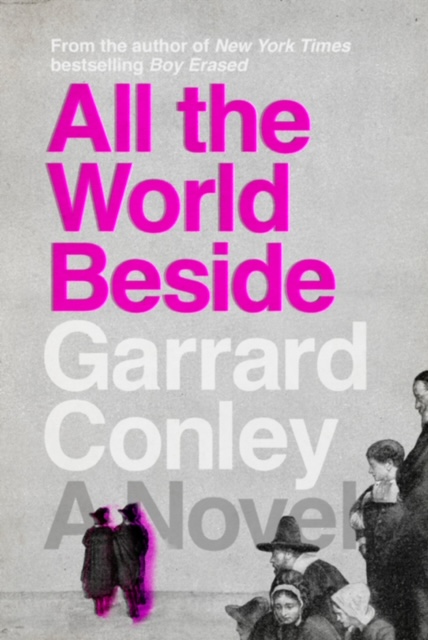

Though Garrard Conley’s transcendent debut, All the World Beside, is ostensibly about an eighteenth century gay love affair between Arthur Lyman, a physician, and Nathaniel Whitfield, a reverend, the novel is chiefly concerned with the nature of desire and the salvation of the soul.

Though Garrard Conley’s transcendent debut, All the World Beside, is ostensibly about an eighteenth century gay love affair between Arthur Lyman, a physician, and Nathaniel Whitfield, a reverend, the novel is chiefly concerned with the nature of desire and the salvation of the soul. Carolyn Forché is the author of five books of poetry, most recently In the Lateness of the World(Penguin Press, 2020), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and also Blue Hour (2004), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, The Angel of History(1995), winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Award, The Country Between Us(1982), winner of the Lamont Prize of the Academy of American Poets, and Gathering the Tribes (1976), winner of the Yale Series of Young Poets Prize.

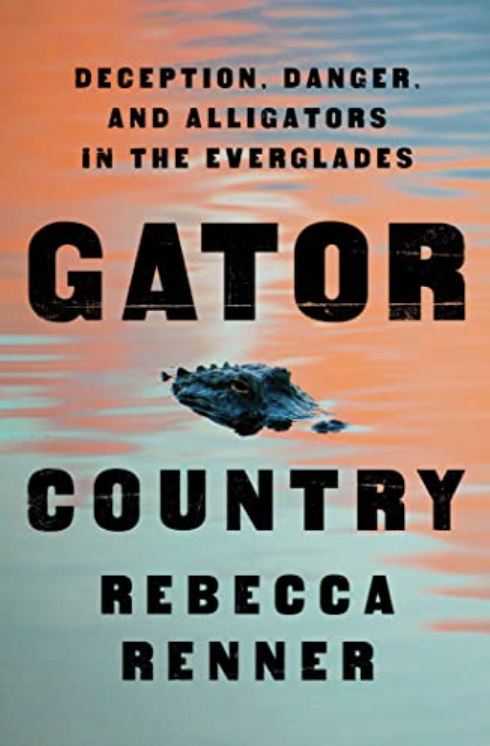

Carolyn Forché is the author of five books of poetry, most recently In the Lateness of the World(Penguin Press, 2020), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and also Blue Hour (2004), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, The Angel of History(1995), winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Award, The Country Between Us(1982), winner of the Lamont Prize of the Academy of American Poets, and Gathering the Tribes (1976), winner of the Yale Series of Young Poets Prize. Equal parts true crime and an exploration of Florida folktales, veteran journalist Rebecca Renner weaves together a thought-provoking nonfiction debut with Gator Country: Deception, Danger, and Alligators in the Everglades. Renner quickly delivers on the promise of the book’s provocative title, sharing truths more thrilling than fiction as she intertwines impassioned narratives and dispels myths surrounding conservation.

Equal parts true crime and an exploration of Florida folktales, veteran journalist Rebecca Renner weaves together a thought-provoking nonfiction debut with Gator Country: Deception, Danger, and Alligators in the Everglades. Renner quickly delivers on the promise of the book’s provocative title, sharing truths more thrilling than fiction as she intertwines impassioned narratives and dispels myths surrounding conservation.

Hurricane Season is a noir thriller about fighting and addiction, prison and drugs; but more than that, it is a love story set in the carnage of an America wrecked by inequality.

Hurricane Season is a noir thriller about fighting and addiction, prison and drugs; but more than that, it is a love story set in the carnage of an America wrecked by inequality. Mark Powell is the author of seven novels, including Lioness, Small Treasons–a SIBA Okra Pick, and a Southern Living Best Book of the Year–and Hurricane Season. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Breadloaf and Sewanee Writers’ Conferences, and twice from the Fulbright Foundation to Slovakia and Romania. In 2009, he received the Chaffin Award for contributions to Appalachian literature. He has written about Southern culture and music for the Oxford American, the war in Ukraine for The Daily Beast, and his dog for Garden & Gun. He holds degrees from the Citadel, the University of South Carolina, and Yale Divinity School, and directs the creative writing program at Appalachian State University.

Mark Powell is the author of seven novels, including Lioness, Small Treasons–a SIBA Okra Pick, and a Southern Living Best Book of the Year–and Hurricane Season. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Breadloaf and Sewanee Writers’ Conferences, and twice from the Fulbright Foundation to Slovakia and Romania. In 2009, he received the Chaffin Award for contributions to Appalachian literature. He has written about Southern culture and music for the Oxford American, the war in Ukraine for The Daily Beast, and his dog for Garden & Gun. He holds degrees from the Citadel, the University of South Carolina, and Yale Divinity School, and directs the creative writing program at Appalachian State University.