1. Consider not reading the e-mail from your cousin Tommy, but then read it. Discover that your Uncle Dave has died. Of an embolism. Very unexpected, as is the case with these things. The e-mail notes the date, time, and location of the funeral. It is signed “best, Tommy.” Struggle with how this makes you feel. It’s been at least ten years since you’ve seen any of your relatives. Your mother’s funeral was the last time. You can’t believe how long it’s been. Ask yourself what you’ve even been doing in all that time. Decompressing is the only answer that comes to mind.

2. Take a Greyhound to Harrisburg to share Tommy’s grief as well as the grief of your Aunt Joan and Tommy’s twin sister Linda. Your own grief is of course less severe than theirs, but you are family and are grieving in appropriate amounts. Think about how your mother would have admonished you if you told her that the funeral were being held at a particularly bad time in your life, making it very inconvenient for you to attend.

3. Struggle to maintain your composure during the service, which is as anxiety inducing as anyone could have purposely arranged. Wonder who these people are. Assume they’re probably wondering the same about you. Shake hands with Tommy but don’t approach Linda or Aunt Joan, who seem almost too bereft at the cemetery, under a purpling sky that feels so close you could touch it. Imagine yourself being carried off by birds.

4. After the service, just as it begins to rain, accept a ride to the house from one of the other funeral attendees, a solemn man in his 50s, perhaps a business acquaintance of Uncle Dave’s. Tell him that you are the nephew. Smile and nod when he says, “Oh, the one from the city.” Thank him for his kindness when he offers his condolences. In the car, a twenty-year-old Acura kept in good trim, when he asks whether you mind if he smokes, ask him whether he minds if you vomit. Drive the rest of the way in silence.

5. Stand in the living room eating finger foods and drinking cocktails. The rain is falling in unbroken sheets, white noise humming in the background like classical music played at low volume. The boyfriend or fiancée of one of Linda’s friends, Dom or Don or something, hovers by the rolling bar and threatens with a drink anyone who ventures too close. Due mostly to these predations you’re on your third gin and tonic, which he keeps calling G&Ts. “Need another G&T?” he asks, you’re sure only trying to be of help in your family’s time of need. “Looking a little dry there, my man.” Watch him pick up some ice cubes with his fingers, which someone really ought to talk to him about—the tongs are right there. But, trying not to think about vectors of germ transmission, accept the drink, thank him, and then stand inconspicuously in front of a cluster of family photos. The largest photo is of Linda and Tommy at Epcot Center in their 90s clothes, lorded over by Uncle Dave and Aunt Joan. Picture their teenage resentment as a heavy, opaque liquid oozing right out of the photo.

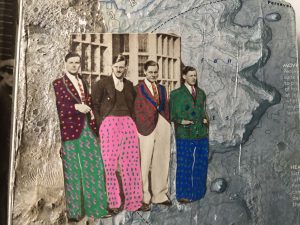

6. Notice how the house feels like a place of pretty negative juju. Likewise Harrisburg in general, which you haven’t visited since you yourself wore appalling 90s clothes. You’ve come to associate both the house and Harrisburg with many painful instances of youth. Recall the day in 1992 when Uncle Dave body shamed you in front of basically the whole family. How afterwards you’d imagine him stealing away into the night to gleefully commit crimes. You did this to deflect his criticism, to make these the savage words of a vile criminal rather than the casual insults of a family member. But also, if he had no compunctions about reducing his only nephew to tears, imagine what he must have been capable of doing to complete strangers. Or his children. Looking at the raggedy group of mourners, wonder what they actually know about him. Walk to the buffet table to gnaw on a baby carrot.

7. While gnawing, try to remember past instances of positivity and bonding with your cousins since they are currently consumed by grief. Or so you imagine. Your uncle was not a warm man. No one would ever have said that about him, yet here people are in his home, or more correctly former home, celebrating his life. Recall a weekend visit when Uncle Dave pulled Tommy’s arm behind his back at a cruel angle for some offhand comment he’d made about the Penguins. How Linda had tried to intervene while you only sat there frozen to the spot. Remember how she yelled, “Let him go, Dad!” and the speed with which he then turned his anger on her for merely trying to defend her brother. Over hockey, no less!

8. Recall how you dissociated from the scene, even though back then you lacked the word for it. How you saw it instead as a tableau, not anything you were involved in or even necessarily present for. Witness it from a remove, as though watching it on TV or through the illuminated dining room window of a house you are walking past at night. Note your uncle’s hair, how the word that comes to mind is “yellow” rather than “blond.” See Aunt Joan smiling nervously—but at who? At you?—as though this gesture would exonerate Dave, excusing his behavior—his violence towards his children, to call it what it was—as a small peccadillo, as “Oh, you know how Dave gets sometimes.” See Tommy, dark haired like his mother, thin still at the time, having not yet started to lift weights in the garage, something you only now realize might have had to do with his father. See brave Linda, who looks like a beautiful and young female version of Uncle Dave, which she did her best to rid herself of at some point in her twenties when she got a wholly unnecessary nose job and began dyeing her hair red. She is the one to challenge him, not Joan, not Tommy, certainly not you. Note your relief and surprise when Uncle Dave suddenly lets the whole thing go, drops Tommy’s arm and reaches quickly, automatically for his beer, and how you all eat in silence until, finally, Aunt Joan turns to you and asks if you’re looking forward to seeing Santa at the mall the following day.

9. No. That’s not it. You weren’t a Santa-visiting child then. You were older. You and Tommy and Linda were in your early teens. Instead of Santa, you would have gone on long aimless walks together with some of their friends and smoked cigarettes and shared a small bottle of pilfered peppermint schnapps, you always on the outside of the group, the interloper, unable to really talk to anyone except for Linda. Recall their Harrisburg idioms, the slang you struggled to make sense of. The inside jokes you were not privy to, because Tommy made it abundantly clear that bringing you along was an obligation and not something he would have preferred to do.

10. Take a moment to acknowledge your gratitude for Dr. Becky and the tools she has given you for addressing and processing your trauma. Recall the body shaming incident again, only now recall it without the shame. You did not deserve that. Let it go. See? See how much processing you’ve done already? Take another sip of the G&T.

11. Also acknowledge that, despite the processing and healing, your current level of distress is exacerbated by the realization that Tommy has surely inherited some of these traits from his father. Things like that are passed down, cycles perpetuated, etc. Dr. Becky insists that part of what we must do to achieve healthy personal growth is to identify and nullify negative patterns. Tommy is clearly the victim of very powerful negative patterns, as evidenced by the time when, as kids, he deliberately pushed you into a patch of nettles. Recall your mother holding a cold washcloth to your lower back.

12. Wander back to the photos. On the same wall is a shelf on which sits an award statuette engraved with Uncle Dave’s name. Realize there is a lot you didn’t know about him. We are, after all, complex animals. Wonder what you could do in your own life to one day be worthy of an award. Consider doing something for children. Or better yet: orphans. You yourself are an orphan, which strikes you as an odd thing to be at 37.

13. Turn around when someone clears their throat behind you. Discover that Tommy has snuck up on you, which you take as further proof of his dilapidated mental state. “Gary, what are you doing with Dad’s award?” he says. You’re surprised to see that you’re holding the award—a hunk of Lucite in the shape of two hands doing a handshake bearing the words Harrisburg Order of Civic Friendship, Dave K. Lowry, 1997. Even with Tommy standing there with an accusatory look on his face, take a moment to run your fingers over its delicate edges. “You know Dad loved that award,” he says, “so maybe don’t mess around and break it, huh?” This could be a humiliation technique, but he’s not entirely wrong. There are some clearly flimsy parts sticking out at the ends of the Lucite arms. They could snap off. “You think I need this today?” Tommy says, eyeing your G&T. He holds out his hand and you put the award in it. “The glass, Gary,” he says and hands back the statuette. “Back on the shelf, and watch the drinking, okay?”

14. Mentally replay one of Dr. Becky’s DVDs, the one in which she says that inner growth often results from placing oneself in unfamiliar surroundings and seeing how one gets on under the duress of not knowing anybody or even knowing where to go for a decent sandwich. Here you are in Harrisburg, which has grown unfamiliar over the many years of your absence, trying to glean positivity at a funeral. You’ve read that this is how boys become men in Africa. Not by traveling to Harrisburg, but rather by going off into the wilderness to fend for themselves and possibly entering into combat with a lion, and additionally without the convenience and security of their houses and families. And when they return to their houses post-wilderness, they are changed. Positive, Growing Change. Although more likely they live in huts.

15. Careful to avoid detection by Tommy, head to the rolling bar and accept Dom’s (?) offer of another G&T. Then, in need of some peace, sneak off to the pantry where instead of peace you discover Linda crying into a large sack of flour. Wonder briefly about appropriate levels of grief and about catharsis and the various ways in which we as damaged human animals express our many emotions. It’s been years since you’ve given any thought to Uncle Dave’s penchant for casual cruelty or whatever his specialty was, but being here now, supporting your family, you can feel in your bones that he has misused people in bad ways. Wonder if there’s a sense of relief in Linda’s tears. Could a human even discern that? Maybe one of those cancer-detecting dogs could. Gulp down the last of the G&T and pat her reassuringly on the shoulder. When you do this, she jumps like a frightened kitten and looks at you with huge red eyes. “Oh, Gary,” she says, her shock giving way to arms being thrown around your neck.

16. Take this embrace as a sign that the healing can begin. Linda must acknowledge the awfulness of the past in order to begin the rebuilding! Over her sobs, say, “That’s right, Linda. Let it out.” And boy, does she. Soon she’s practically having a seizure. Recall how Dr. Becky says that sometimes when our pain has been sublimated for too long an inner dam must first break before we can allow the river of our emotions to flow once again at a healthy rate. Tell her she’s not alone. Tell her you know all too well that her father was a monster.

17. Feel how, with this avowal of solidarity, her sobs lessen. Her river resumes its correct path! Feel proud that you’ve taken the first beautiful step of an important journey, together as family. She pulls away. “What did you just say?” she asks.

18. Say to her, “We can overcome our trauma!” Say to her, “Your dad can’t make you—or anyone—suffer anymore!”

19. Smile as she calls out for Tommy. Maybe you’ve misjudged your own cousin. Surely he’s suffered as well. Been victimized at great length and intensity, etc. He must be in need of some dam-breaking, too. Identify and nullify, is what you will tell him. This is where it begins! Tommy arrives in seconds.

20. Listen as Linda says, “Gary, tell Tommy what you just said to me.” Here’s your chance. You’ll do Mom proud in terms of familial supportiveness! Put a hand on each of their shoulders. Say to them, “I know how hard this is. The complex emotions, the years of trauma. But we can change this.” The looks they’re giving you? These are grateful looks. Say to them, “Whatever awful things your dad did, we are not hopeless! We can heal.”

21. Take note of Tommy’s confusion, as though conflicting sentiments are waging an important inner battle. Ask him, “He body shamed me, do you remember that?” Ask him, “Did he beat you?” Turn to Linda, knowing that no amount of hurt and damage is unrecoverable from, and ask her, “Did he…touch you?” Watch her eyes go glassy with tears. The healing starts here, is the message you are getting in huge neon letters even as Linda again erupts into sobs.

22. Wonder how you should react when Tommy says, “That’s it. Get the fuck out of here, Gary.” And before you realize it, he’s got you by the arm, painfully jostling you out of the pantry.

23. Protest as he drags you through the house, but do it quietly so as not to bring up family skeletons in front of strangers. But even so, everyone turns to watch this parade of misunderstanding, because that’s surely what this is. Experience genuine confusion when the buffet table gets knocked over. Look in the direction of the breaking China, and as you’re being pushed out the door, see Aunt Joan’s questioning expression. Resist the urge to struggle as Tommy hands you off to Dom, who gives you a weak smile as he escorts you down the driveway. Accept that he’s just trying to be the good guy here, but he doesn’t understand. He’s not family. Up on the porch, see Tommy with his arms around Linda and Aunt Joan who are both crying, clearly in the midst of catharsis, now framed by a bunch of moochers and gawkers.

24. Yell to them, “We need to address underlying traumas! We have to acknowledge these things in order to heal!” Dom, you’re almost certain it’s Dom, pushes you into the passenger seat of his Nissan. Accept that leaving is for the best. You’ll mend fences later, at a less fraught time. Tell Dom that you’d like to go to the Greyhound station.

25. Be surprised to find yourself, again and again, thusly on fire, despite your widely acknowledged talent for flammability.

26. Consider worrying about how Dom drives, because surely he’s driving too fast for the road conditions. You don’t know how safe a driver he is on a good day, let alone now, in this downpour. His instincts could be way off.

27. “Look,” he says, “it’s a rough time for everybody right now. You gotta let the family work through their grief without adding to it, is what I’m saying.”

28. Doing your best to conceal your fury, say to him, “The family? I am the family. I am facilitating! What about you, Dom? You’re a stranger picking up ice cubes with your fingers!”

29. Accept the rightness of your argument when he doesn’t respond, and instead turns on the defrost. Listen to the whooshing air. “It’s actually Don,” he says after a while.

30. Unbuckle your seatbelt when you arrive at the station. As you open the door, Don says, “Seems like you’re carrying around a lot of sadness, man. I hope you can work through that.”

31. The gall of this guy. The absolute nerve. Let this remark go, however, because what are you going to say? What could you even say to this kind of gross oversimplification? Who isn’t carrying around lots of stuff, Don? Exit the car and walk through the rain with your dignity intact.

32. In the station, watch as a man chides several children while attempting to wrangle an old woman displaying all the classic signs of dementia; watch a teenaged boy hiss racial slurs into his phone; watch an elderly couple carrying garbage bags and disintegrating suitcases held together by peeling duct tape. But regardless of this cavalcade of misery, the station is a relief. It’s times like this when you are thankful that you do your shopping almost exclusively with a Citizens Bank Mondo Mileage Card. Travel-related purchases are easily reimbursed with bonus miles, and, thanks to this, attending Uncle Dave’s funeral has cost you only $14 round trip. Change your reservation to the next available Pittsburgh-bound bus, another thing that’s a snap with Mondo Miles. Luckily, there’s a bus leaving in 40 minutes.

33. After retrieving your ticket, hold a free weekly newspaper over your head and step back into the rain to find a liquor store. Circumstances being as they are, you can justify a pint of bourbon. Allow only a small amount of guilt to creep in. There’s actually a whole DVD chapter devoted to stress-propelled intoxication (Disk 4, chapter 2: What Not to Do [Although We Desperately Want To]!). Your sense, however, is that Dr. Becky would understand the need for the occasional drink, given that what you’re aiming for is incremental progress. Going “cold turkey” would be a bit much to ask of anyone, despite Mom’s near constant assertions to the contrary. So allow yourself a drink when necessary and ask quietly for understanding. You can’t be too hard on yourself all the time, is the thing.

34. Back in the station, stealthily sip bourbon from the bottle, which is camouflaged in your backpack. Count the minutes until you’ll be at home and can process the day’s events in a productive manner. Listen to a garbled voice spit out departure information from an overhead speaker. Watch the other Pittsburgh-bound passengers make their way to the gate. Take your place at the end of the line. Sip bourbon from your backpack.

35. Notice, just as the line starts moving, a sudden and insistent discomfort in your bowels. Run, they instruct you with grave seriousness, evacuate with all possible haste.

36. Clutch your stomach as you rush past a row of urinals. Observe each one flushing in turn—a salute to all the times you have communed with toilets! Consider how urine is sterile when it leaves the body—the purest part of you escaping. Bright like liquid sun hitting the gleaming white porcelain and slowly dissolving the innocent pink of the urinal cake. Then the flush. Water rushing your urine seaward in subterranean rapids. Part of you joining the biggest thing in the whole world, the sea, and it is changed by you, not you by it.

37. Attempt not to dwell on the condition of the stall. Refuse to dwell. Think instead of the kind and thoughtful inclusion by the restroom designers of a dispenser full of hygienic seat covers. But then, before you can even make use of them, an announcement crackles through the speaker: Final boarding, 12:45 bus to Pittsburgh. Last call. Since you cannot fathom missing the bus, continue clenching and run.

38. Step carefully onto the bus. Shuffle down the aisle. Notice the other passengers looking at you, possibly sensing some inherent weakness of character for being the last person onboard, for being so borderline irresponsible. Go directly to the toilet but stop when the driver says sternly through the intercom that passengers must remain in their seats until the bus is moving. Find a seat and try to ignore the rumble of the engine. The driver lists all the stops you’ll be making, really taking his time with it, but then, mercifully, pulls out of the station. Get up and lurch down the aisle while the driver casts his evil eye at you in the mirror. Decide that you don’t care. Let his curses come for you! Lock yourself in the claustrophobic’s nightmare masquerading as a toilet. Breathe through your mouth as you drape the seat with hygienic covers and then drop your pants and sit. Briefly consider thanking God for small miracles such as this. Allow yourself a few sips of bourbon.

39. Wake to an insistent knocking at the door. You can’t deny that you are quite drunk. Slap the life back into your legs. Exit the bathroom to discover half a dozen surly passengers waiting. Consider apologizing but don’t. A man in a western shirt with a braided goatee sneers at you. Does he know what you’re going through? Of course not! This is another life lesson: Reserve your judgment! You do not know how hard others have it! Walk back to your seat. The duo of teenaged girls sitting across the aisle look at you and giggle. They have no idea what unpleasantness awaits them, and you don’t want to be the one to tell them of all the heartbreak and job loss and stretch marks in their futures even though you are feeling more than a little pained by their behavior. As you approach Pittsburgh, take solace in watching the landscape grow familiar and soothing, the aqueous quality of the light that is particular to the Steel City.

40. Let your thoughts turn to Tommy, Linda, and Aunt Joan. You have to believe they’ll eventually be able to acknowledge their pain. They’ll see that your actions, even if perhaps the timing could have been a bit better, were only in service of ripping the Band-Aid off to allow the healing to begin.

41. Transfer to a city bus that stops three blocks from your apartment. Ride with your forehead resting against the window and feel the grease of the last forehead to rest there, but accept that the soothing coolness of the windowpane is more important than any potential forehead bacteria. Downtown on a weekday afternoon is so awful you can hardly stand it and yet there are people all over the place, completely at ease, closing business deals or whatever, all without a single thought to the probably impending cataclysmic events in their lives. Or maybe they’re not worried about that. Maybe they’ve already found Positive, Growing Change. At a red light, watch a man kiss a woman on both cheeks as they meet crossing the street. Right in the middle of the crosswalk! It’s the most European thing you’ve ever seen.

42. Arrive at your apartment and acknowledge your gratitude that you have not, to your knowledge, been burglarized. Lock the door behind you, slide the deadbolt shut, and plop down into the comforting embrace of your sofa. Open your backpack for the bourbon and, along with the bottle, find Uncle Dave’s award. Become aware of the hot buzzing in your head, the grotesque cramping in your stomach: the hallmarks of an impending shame-spiral. This is not due to the guilt of having “stolen” a cherished family keepsake, but due to the embarrassment at being thought of by the family as someone who would steal a cherished family keepsake. Become sickened by the idea that you might be judged so unfairly. You can offer no explanation for the appearance of the award in your backpack—this alone should exonerate you! Accept the overwhelming need for a drink. The bourbon is all gone except for a doleful little swish. Drink it and hope for the best.

43. Dr. Becky says it’s good to have a support system in place for when we are handed lemons. Look at the clock. Almost 6:30pm, which is too late to call Gil Zwieback at the counseling center to ask for advice on alternate support strategies. You’ve called him at home before and he seemed genuinely surprised by it. But you told him his phone number was there on the internet as a matter of public record. He said that you should probably talk about boundaries.

44. Become aware of your growing anxiety. You need to find your center, reevaluate, and concentrate on how to return the award unnoticed and unblamed. Put on the Your Power to Heal! DVDs, starting right at the beginning—Disk 1: You Are Also Worthy of Love and, By the Way, Your Emotions Are Valid, Too. Notice your anxiety already beginning to ebb during the opening credits. Dr. Becky is a godsend. Feel a pang as she appears on screen. A pang of what? Comfort? Desire? Can it just be a non-specific pang? A slight but not unpleasant pain in your side.

45. Follow Dr. Becky’s guided meditation and gradually feel a renewed sense of calm. You will find a way to address the award. Even though at this very moment Tommy is surely impugning your character to anyone within earshot, even though your family is surely already referring to you as a petty thief, deepening their suspicion that you are the “black sheep,” you will find a way to fix this. Do the focused breathing exercises and a round of affirmations. With each wave washing over the rocks (the DVDs are filmed on an inspiring Hawaiian beach), feel your desire for calmness manifest itself. Repeat Disk 1’s mantras: I am alive in this moment! I am present! I will persevere! She speaks softly but confidently over the crashing waves, but not in a sexual way, although who can say what other people find arousing? Repeat aloud: I am here, and no one is any more deserving of happiness than me.

46. Meet Dr. Becky on the beach. The waves lap at your bare feet and together you intone mantras over the roar of the ocean, drowning out all the cataclysm and disharmony that the world holds in store for anyone. Then, just as the sun dips into the water: a swell of fiery Hawaiian drumming!

47. Wake up in the dark, the weight of the Lucite hands on your chest, the sunset replaced by the DVD player’s logo slowly floating across the screen, caroming from wall to wall. Note the discomfort in your head. Your phone chimes. Six voicemails from Tommy. In addition to the hangover, find that your right ear is completely stopped-up. This has happened before. Thanks to a mishap in the bathtub a few years ago, you have a perforated eardrum, and this, coupled with chronic sinus issues, sometimes leads to your ear becoming stopped-up, plunging you into temporary partial deafness. It’s maddening—the deafness, the loss of equilibrium, the pressure in your sinuses that feels like a leather strap being tightened. There’s also nothing you can do about it except take a handful of Mucinex, put a hot washcloth over your ear, and wait it out. But that can take hours to have any effect. Stand up a bit unevenly and pace the length of your apartment. Rap your knuckles along your upper jaw hoping to loosen the clog of fluid. You’ve been here before. Every time this happens you’re sure it’ll be permanent. Panic overtakes any rational part of you and even Dr. Becky’s mantras can feel useless.

48. Spin in circles in the middle of the living room. You don’t know why or how spinning ever became a coping mechanism, but when the sinus/ear thing happens it’s never long before you find yourself doing it. It must have helped on some unremembered occasion. Peeking over the top of your panic like it is a wall, think that if you just spin quickly enough the centrifugal force will eject a globule of mucus and you won’t end up being discovered deaf and dead of a panic attack, alone in your apartment.

49. If Dr. Becky has any plans for another DVD installment, which you sincerely hope she does, realize that she’d do well to address this intersection of emotional and physical discomfort. She could even include you as an expert on the subject. Return to the beach. She’ll say something like, “Friends, with me today is a very special guest. A man who is no stranger to suffering and in fact has met his own personal demons head on to come out the other side like a phoenix rising from the ashes of personal trauma!” And you will nod wisely along.

50. Say to the camera, “Trust me when I tell you that no matter how bad you have had it or are currently having it, I can empathize! Do you want to talk about negative life-changes coupled with physical ailments? Let us not even talk about that! Let us instead talk about our ability to surmount these challenges! Let us instead talk about how no amount of suffering is too great for us to overcome!”

51. Think about how you’d act if you were ever to meet Dr. Becky in person. Would her hair smell like you’ve imagined, like coconut? Her face is the very embodiment of inner calm and personal fulfillment. Consider how you’d thank her for her DVDs, acknowledging how helpful they’ve been for you. Although it’s not as if you were some basketcase slob before the DVDs. You were simply in need of some extra tools. You’ve been through a lot. Your mother’s death, for instance. Recall her in those final months. Mostly she was this zombie presence in the house, lying like a small bundle of sticks in her rented hospital bed, out of her senses with morphine. Recall the occasional lucid moments in which her eyes became unclouded and she was able to lament all the things she would never have the chance to do now, like visiting her favorite beach in Maine again, like the bird painting class she’d looked up online. Recall how you became thankful for the morphine because, at least, it dulled those regrets for her.

52. Remember going to Darlene’s apartment, who, even though you hadn’t seen her for years, was still kind enough to obtain marijuana for you, which you then baked into a batch of cookies and fed your mother tiny bites of. She could hardly swallow anymore because of the tumors, but smoking it would have been impossible. Recall how, after she choked down a few bites, nothing happened for a long time, but then just when you thought the marijuana would have no effect on her she asked to be taken for a drive. So you bundled her up in her heaviest coat, although by then you could have fit two of her in it, she was so small, and you half carried her to the car and drove. It didn’t matter where, she told you, she just wanted to look at the clouds. They were so interesting all of a sudden, she said.

53. Think back on how grateful you were later that night once she was asleep and how you called Darlene to thank her for the marijuana. But she couldn’t talk, she said, because her baby needed to be bathed.

54. Recall your rage at your mother’s pancreas. That bullshit little organ. Wonder if it’s even an organ. What does it do? How can something so seemingly inconsequential—does anyone aside from doctors even know what the fuck it does?—decimate a body like that? What goddamn right does it have?

55. Continue spinning, continue hoping to dislodge whatever is clogging your ear. As you gain speed, marvel at how the meager interior of your apartment is transformed into a wonderful pattern of horizontal stripes. The room blurs, close your eyes and keep going, gaining speed.

56. Hit the wall with your head and collapse. As you look around, confused, watch the room gradually right itself. You’ve knocked a photo off the wall. The glass is intact so you pick it up. It’s you as a little kid, Mom and Dad on either side, arms thrown around each other and you, too, in some approximation of a group hug. Look at yourself and wonder who this smiling little doofus even is.

57. Touch the right side of your forehead and locate a hot, tender bump. Your head is chirping like it’s alive with grasshoppers, and for a moment all you can think of is mid-summer and Darlene, and the time you went to that bed and breakfast in the Poconos. There were grasshoppers chirping everywhere at night, so loud you’d have to raise your voice to make yourself heard. But then you got used to the chirping, you got used to Darlene, to her lying on the four-poster waiting for you, and now here in your apartment the chirping fades as well and you hear only a dull noise like some piece of metal that’s been clanged and left to ring itself out. A distant, imperfect bell.

58. Recall Uncle Dave and Aunt Joan welcoming you into their home once, when Mom and Dad were fighting especially badly. They’re both smiling at you as Mom drops you off and without a word gets back into her old yellow Malibu to return to Pittsburgh where she will fight some more with Dad and then leave him at the end of the summer and then you and Dad will spend the fall alone together, him sitting often in brooding silence staring out the window, until Mom comes back to get you and you move into an apartment with her and then Dad eventually moves to Scranton. Wish that you’d had Dr. Becky back then.

59. Feel the inexplicable need to go outside. Maybe the nighttime air will let you work on positive solutions. Maybe being outside will give you the necessary space to process everything that happened at Uncle Dave’s funeral and the unpleasantness associated with trying to foster an environment conducive to healing. Maybe you’ll be able to address the accidental theft of the award and the shame surrounding that. Maybe the stopped-up ear too. Identify and nullify!

60. Marvel at Pittsburgh at night! Dark and humid and quiet. There’s no one on the street, not even raccoons. Feel grateful for the solitude. Walk unevenly, which is now partly due to the ear and partly due to the head konking. Notice that within a block the cool air is already working its magic! Keep walking. Feel the blood rushing around inside of you. Think: If walking is this beneficial, imagine what running will do!

61. Run. Soon there’s something happening. Your hearing isn’t back yet, but over the rush of blood in your head tell yourself that you can hear your footsteps. Tell yourself that you can hear the control boxes at each intersection clicking over to change the traffic lights as you pass. You haven’t run in years! It’s wonderful. Think back on other times you’ve suffered from the ear thing. Wish that you’d thought to run then. Watch as scraps of litter blow along the street seemingly under their own power. Look down Franklin Street and see the broken discs of light from streetlamps where they spill from the sidewalk onto the asphalt and wonder if this is all simply what God, in whatever personal way we each conceive of a higher power, has planned for you. Perhaps these trials are yours to endure and this suffering will eventually make you a better person; no more need for coping mechanisms or mantras. But until that day comes, if it comes, tell yourself that you’ll go on bearing your specific crosses with hopeful dignity. You will repeat your mantras and, when necessary, run. Your ear hasn’t drained yet, but it will. The pressure will lessen with a long triumphant squeal. You’ll spit the mucus, tinged with iron-tasting blood, victoriously into the sink and that marbled glob will slide down the white porcelain into the drain and be gone. Another part of you joining the water, rushing seaward, home. And likewise, at some future point your family issues will be resolved.

62. Notice Uncle Dave’s award in your hand.

63. As you run, holding the shaking hands, think about how maybe you could still return it unnoticed. Tommy’s voicemails might be unrelated. They might be his guilt manifesting itself at having treated you so unfairly. Maybe he’s been calling you over and over (six times!) to apologize. You could take the next bus back to Harrisburg, slip into the house, and put it back. Tommy probably hasn’t even noticed that it’s gone. Things are never beyond repair. Maybe you could all go for brunch!

64. Allow yourself to be buoyed by the sudden thought that despite the feeling of permanence in each individual moment, eventually things may change. The idea that things will never change is something that’s been ingrained in us since birth. You know this for a sad fact, just like you know there are hands at the ends of your arms—you’re not saying that will never change, who knows? Your hands could get chopped off tomorrow! You’re just using it as a point of reference. But through lots of hard work utilizing Dr. Becky’s system you’ve learned that things frequently do change, although more often than not in ways we don’t like. For one, you’re not getting any younger. Kid yourself and say, Your hair’s not thinning up top! No one you’ve ever loved has left or died! These are changes you could do without. Ask God to let you keep your hands, let them stay, let them not leave you at an inopportune time!

65. Look about 100 yards ahead of you—someone, a young woman, is standing on an overpass looking down onto the train tracks. Could she also be suffering unjustly from some manner of panic or injury? But even if so, what can you do? Interact somehow? Place a sympathetic hand on a stranger’s shoulder? That didn’t even work so hot with cousin Linda earlier! But still, slow down and walk cautiously her way. Sharing even just a small moment of human interaction might help during whatever personal life issue she’s undoubtedly facing. Maybe just a quick nod? As in: Even though we are both in this moment alone, in a different but equally valid sense we are also not.

66. Become struck, the closer you get, by this woman’s resemblance to Dr. Becky. It’s uncanny. Reconsider approaching. Decide to just watch for a moment from a discreet distance because, after all, despite any desire for commiseration you recognize that sometimes the best thing is simply to be left alone with your thoughts. She might even lash out, misunderstanding your intentions, irascible and confused as God knows we all have every right to be. She really does bear Dr. Becky a striking resemblance despite how you’ve never once seen Dr. Becky standing on an overpass at night. But even lacking the proper context this is somehow comforting. You’re not thinking of the stopped-up ear or Tommy’s yelling or even your guilt about the award. You’re simply aware of your heartbeat and breathing and how both are now slow and even. This isn’t either how you would have imagined Dr. Becky being dressed in her private, off-camera life. You’d have thought she’d be wearing perhaps a skirt and blazer. A power suit. Or is it called a pantsuit now? The woman on the overpass has on frayed jeans and a sweatshirt that’s several sizes too big.

67. The thing is, the look on her face is just awful. Your heart goes out to her. Despite whatever personal shortcomings you’re plagued with, or even perhaps because of these shortcomings, you can recognize suffering in others and feel that someone should help alleviate that suffering if the opportunity presents itself. Realize that in this moment you want nothing more than to be the cause of this woman feeling any amount of, you guess, less aloneness. If you can do something to affect any kind of Positive, Growing Change for her, it would also surely lessen your own burdens. That must be how Dr. Becky feels. Approach her with a deep sense of calm and purpose, pushing all your feelings of reluctance down into a tiny ball that you will address later at an appropriate time.

68. Watch as she cranes her head to look further down the tracks, perhaps even hoping to alight on some small background detail that will provide her with solace. A bird taking flight, a cloud teased into a pleasing shape. But instead of that you see what she’s actually looking at. An approaching train. As it gets closer she swings a leg over the overpass’s low wall.

69. Overcoming whatever social constraints exist in cases such as this, shout at her: “Hey!” She looks at you with you don’t know what in her eyes, but is maybe fear? Drop into a sprint as she looks down at the tracks again. Shout: “Wait!”

70. She’s got both legs out over the tracks now, the laces of her dirty white sneakers dangling untied. With maybe 30 yards between you still, you can finally see her face clearly. She’s young but her forehead is crisscrossed with lines. Her lips are pale and thin. Her eyes glow dully under stringy bangs. Realize that she looks nothing like Dr. Becky. She looks like Dr. Becky post-hunger strike. Dr. Becky’s cousin on her third round of chemo. Yell, “No, wait!” She looks up again. Yell, “Hey, no!”

71. Run. Close the distance between yourself and this woman as she scoots tentatively forward. Take this as a sign that she hasn’t made up her mind yet. Feel your heart beating wildly. Ignore it. 20 yards. You’ll throw yourself forward and catch her because you have no choice. See yourself doing this: Leaping, diving, grabbing hold of her and pulling her back onto the overpass. Because if you do this, do only this one thing, then it will be okay. Then so much will be okay. You’ll lie together on the sidewalk and she’ll realize what a mistake it would have been. She’ll cry on your shoulder, probably getting snot all over your shirt in the process. You’ll stroke her dirty hair and gradually it will get better. Your ear will drain and your family will be healed and whatever wound has driven her to this will begin to scab over. Whatever fluids you need to expel, you will expel and send home. You’re thinking so clearly now as you fly across those last few yards. It’s almost dawn. The sky brightens, the streetlamps click off, and all your apprehension melts away like frost on a windowpane. Her hands tense on the wall to push herself off. You follow.

72. Manage just barely to make a fist around the shoulder of her sweatshirt. And yes! Yes! She’s heavier than you thought, or maybe you’re weaker than you thought, but you’ve got her. The sweatshirt’s pulled tight but she’s squirming. You have to get a better grip. The collar’s choking her, she’s spitting and gasping but you can hear her clearly over the sound of the train that’s now just beneath you. “Let me fucking go! I want to go!” Think: No way, José! You have to get a better grip. Look down at your other hand.

73. Let go of Uncle Dave’s award and then reach over. Pull with both hands. She’s fighting, squirming, punching. Her wounds must be so deep that this seems like the only way out. But that’s not true. This is just her dam breaking, it has to be. Strain, with every ounce of strength you have, to pull her the rest of the way back as the train finally passes. Collapse together onto the sidewalk. Gasp for air. Your lungs are burning. Your heart, beating its way out of your chest. See Uncle Dave’s award on the ground next to you, broken into pieces. The hands still whole, doing their handshake, but the rest in shards.

74. Look at the woman. She’s on her feet now. You want to tell her about Dr. Becky, about mantras of perseverance, but before you can do this she spits on you, calls you an asshole, and runs off with an arm raised high throwing a middle finger in her wake, her sweatshirt pulled all out of shape, hanging off her like a tarp.

75. Stay where you are and work to get your breathing under control. It’s okay. There it is. You can do it. Notice that your ear is unclogged. You can hear everything. So many tiny miracles! A car alarm down the street; the retreating train siren—both suddenly miracles. Look up as a car drives along the overpass and slows near you. See the man driving it roll his window down. Hear—hear!—him laugh at you and then watch him speed away. But what is this if not evidence of his own personal trauma? And what is trauma if not the opportunity to heal?