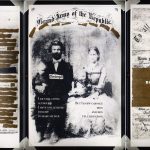

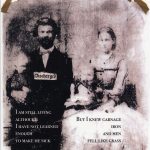

“To All Whom It May Concern” is a triptych of documents from the Civil War that includes: 1. An erasure of the first page of a four-page letter written by Lyman Jones to his parents while he was held a prisoner of war in 1863; 2. A later photo of him with wife and two children; 3. His discharge orders, over which a second erasure is pasted—words cut from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” as published in his 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass.

Category: Aquifer

Two Erasures

In a few months another baby will get to the internet

Still sore and broken

after its husband did wrong

betrayed by the woman

the world.

I was secretly hoping

that his eggs made a litter

because the meltdown didn’t happen

there is new news

that years

will soon spit

newborn shit on their hands

To cover that it’s a ‘man’s world’

I’m certain, therefore delighted.

We are expecting a November

named yesterday.

From his yes and into his sound

like the name of a California town

Somebody spiked the table

with fertility.

Either knocked up or out

and now

that grumbling might be Jesse James

It might be America

baking in her.

“In a few months another baby will get to the internet” is an erasure from a Dlisted.com blog post on 7/9/14 titled “In A Few Months Another Baby Will Get To Call Robert Downey Jr. ‘Daddy.’”

We choose to smile in the face

1.

We choose. We choose to look at time.

We choose fives. We choose zig, else zag.

We choose a lot of things, but,

choose us.

Happiness is enough.

We choose to live—

purpose.

Your scent, your style: try these fragrances.

Secret escape.

Everything is better with purpose.

Find out why.

An empty box is filled with possibilities

(find the bottom).

This box is full.

100%.

Don’t throw it away, it’s too pretty:

a light manufactured by Saint Louis,

owned by

société de produits

or used with permission in a dry place in the USA.

2.

Go.

With absolutely everything.

3.

Purpose in 3 simple steps:

Step 1.

Step 2: pour purpose in a box. Refresh.

Step 3: Unwind. Throw some shoes.

You want to worry.

Trust us. You’ll love it.

“We choose to smile in the face” is an erasure from the text on the back of Purina Purpose Clumping Cat Litter 23-pound box.

Plum Trees, Astray, Verso, A Little Croquis, and Snow Still

Wory Gardn

Seduction

One House Back from One House Down

One House Down by Gianna Russo

Madville Publishing, 2019

Paperback, 96 pages, $17.00

The majority of the fifty-three poems that populate One House Down, Gianna Russo’s second poetry collection, are set in and around Tampa, Florida. As the poet guides us through a bit of Tampa’s history—the noisy streets, the voices of a hundred years and more—we locate the growth of a community. The constant is Russo, a poet of Tampa—remarkable and protean, not unlike the city itself. Russo’s poems are an honest record of a city’s quick evolution, but most importantly, these poems are a love song for the family, friends, and neighbors who inhabit Tampa with her.

One of the collection’s standout poems, “Where Letha Lived,” addresses the value of the places we get to call home. The speaker’s father begins the poem: “You know she helped raise you, says Dad. / They were lovely people. If you went by, she always invited you in.” For the father, it is important that his daughter understand the privilege of acceptance, the willingness of another family to open their home to her. As the poem builds momentum, the speaker declares: “I don’t know how to feel about all this now.” The poet is on the cusp of discovery, and the early placement of the poem in the collection elicits expectation in the reader—will the poet discover how she feels about all this now?

The charm in “Where Letha Lived” lies in how we come to know Letha. About a third of the way into the poem, Russo re-introduces lines and images, and this process of doubling continues to the poem’s end. In a coy bit of plotting, the poem initiates the engagement of our memory. The stories Russo re-tells us about the life of Letha establish a sense of familiarity. Our memories become the speaker’s memories. Letha becomes recognizable. Russo’s use of memory, her coaxing us into our own memories of Letha is not coincidental. Lethe is the river of forgetfulness in Greek mythology. Russo is reaffirming her own fading memory of an important person in her life. The speaker says of Letha, “She must have had a kitchen garden. / Do I remember? No.” The poet also points out the cultural boundaries during this time in her youth: “One end of the street, a clutch of tickseed. / The other end, the Italians, their tomatoes and greens.” She sees, as an adult, the invisible lines of division we are ignorant of in youth—a part of how she feels about all this now.

Russo works in free verse, but she also employs other poetic forms with similar, deft skill. There is an ekphrastic poem, a pantoum, a poem in the form of a cookbook recipe, and a poem in the shape of a standardized test, but the literal centerpiece of One House Down is “Pecha Kucha for Big Guava.” There are interesting and unlikely cultural connections in that title alone. Big Guava is a nickname for Tampa, and pecha kucha is a Japanese presentation method involving twenty slides, each accompanied by twenty seconds of dialogue. American poet Terrance Hayes adapted this storytelling technique for poetry, and Russo puts the form to great use, galvanizing the collection.

Russo’s pecha kucha consists of twenty photographs of Tampa. Similar to the narrative construct of One House Down, the photographs move through time (1920–1954). The photographs are necessary for the poetic form, but the poems that accompany the photographs stand on their own. These poems are so exquisitely written; the photographs are rendered moot. Here, you’ll see what I mean—the poem without the photograph:

She’s standing there like a ghost, but really

it was her house first. Those cabbage palms,

bougainvillea, white gardenia, beauty bush.

Her crone of a house wreathed in cracker rose. Now:

sandspurs, boarded up windows, a locked door.

One House Down is a deep map of Tampa and of the poet’s familial connections to its neighborhoods. It’s not quite written to the scope of Ulysses, but this collection reads like a peripatetic narrative. What the reader discovers is a southern landscape replete with oaks, azaleas, and magnolias. “In the Midst of Magnolia” is a singular, southern poem that is dedicated to Joelle Renee Ashley. Russo conjures the aroma of the magnolia: “Your stories buried in the blooms, the creamy bowls of magnolia.” The alliteration is wonderful. But the speaker struggles to get it right—this poem in dedication: “The fading house on Rainbow Road / where voices ping-ponged in your brain,” or “A raunchy clause where the sexy you stretched herself out.” These descriptions lead to the poem’s conclusion:

The poem I wanted for you has failed me. Here:

On long drives out to your house stars made a cliché of the sky.

There was a gateway to grief and you walked through it.

Magnolia perfume is the gist of it.

The speaker wants us to believe that these final lines are what exist on the other side of failure—how all of us feel, or should feel—about love, about friendship and family, but especially about the places we call home.

The collection ends with “Somewhere Jazz,” a poem of exuberant reflection. Russo writes, “I wanted this to be about the house.” It’s easy to believe the speaker is referring to the poem, but Russo has made this move before—directly telling us where her narrative intentions have gone off the rails. The speaker is talking about the book itself—the house of the book holding all of her loves, “The house where you called down all your ancestors. / Much before the house I thought was me was thrumming— / pure inside with jazz.” And there’s the turn, the moment where the poet figures things out. Russo has become the house she peers out from as the collection begins, and the house she dances within as the narrative of these endearing poems refuses to end, but instead plays on.

Please also see “After the Poetry Reading: A Condom” by Gianna Russo.

November Nineteenth [On Erasure]

This erasure is from Donald Culross Peattie’s An Almanac for Moderns, a book of daily essays on the natural world written in the Midwest and published in 1935. Moore uses the book as part of a daily erasure practice, erasing the correspondent day and seeking to radically transform Peattie’s meditations, dramatically shifting the topic and focus of the original entries.

Peattie, Donald Culross. An Almanac for Moderns. Editions for the Armed Services, 1935.

Of extinction

The Mueller Report, Vol. 2, Page 147 Fairy Tale

Selections from VIOLETS

Voicing Ghosts

MOTHERBABYHOME by Kimberly Campanello

zimZalla Press, 2019

Vellum paper and oak box or readers’ edition book, 796 pages, £47.00 GBP

A vexing problem for the poet is how to write for the dead. Inherent in the endeavor is an appropriation, a betrayal, and a reduction. I know this dynamic well as my first book of poetry, The Sunshine Mine Disaster, was an attempt to speak to/for the 91 miners who died from carbon monoxide poisoning in the most productive silver mine in the United States in 1972. There’s a point where the dead unveil the poet’s futility and hubris, where the dead say “not enough,” where the dead say “too much.”

Or I think of Muriel Rukeyser’s attempt to capture the thousands of deaths caused by silica exposure from the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel disaster in the 1930s. There, she traveled with photographer Nancy Naumburg to study, document, and capture the suffering of the laborers and their families. The result was an abbreviated, incomplete section of U.S. 1, “The Book of the Dead,” where the project resisted containment.

Thus, I come to Kimberly Campanello’s MOTHERBABYHOME, an excavation into the deaths of some 796 infants and children, who were housed from 1926 through 1961 by the St. Mary’s Mother and Baby Home under the administration of the Bon Secours Sisters, on behalf of the Irish State in Tuam, County Galway. These children were lost and buried in unmarked graves. Perhaps thousands of others were illegally adopted. They were, in essence, shame-ridden chattel of the Irish State and the Catholic Church; neither they nor their mothers had bodily autonomy.

Campanello’s work is a 796-page compilation of conceptual and visual poetry, of great expanses of nearly blank pages, disruptions of language and fragments, poly-layered type, explosions of text, all on large, letter-sized sheets of lightly transparent paper. In a brave collaboration with Tom Jenks of zimZalla Press, Campanello constructed both a reader’s edition, a bound paperback volume with a map of the institution grounds on the cover, and an “avant object” edition, a small set of individual copies made on loose sheaths of vellum paper housed in a hand-made oak box. Physically, both editions approximate the size of a coffin that could very well hold the skeletal remains of an infant.

The fragments—while highly manipulated by the poet, as they contort and bleed and reiterate on the page, as they communicate with other fragments visible through the layers of paper—are all external to the poet. They come from contemporaneous letters, documents, reports, decades of anguished cries and discomforting disavowals. They also come from current expressions voiced on the internet and in newspapers in response to the disclosures of the deaths by historian Catherine Corless in 2012. And so, among the fragments are harrowing words of mothers, rationalizations by priests, legalistic dodges by the government, and angry protests by Catholic apologists.

On one hand, it mimics the chatter of our currency—these could be tweets lost in the algorithms—and on the other hand, it channels the dead, directly, in their own words, buried, misaligned, and decomposing on layer, upon layer, upon layer of page. And as an anthropological record, the one lineal linkage is the chronological listing of the identified dead, the infants and children, all in impossibly tiny font (4-point, perhaps), with the years punctuating the individual sections.

One poem is a repetition of a single fragment, “programme of DNA,” reprinted three or four dozen times, overlaying one another, to form tiny stars, coalescing signifiers. Another poem is a four-page catalogue of diseases, ailments, and medical conditions. Clinically, the work on any single page may echo some early 1980s L*A*N*G*U*A*G*E experiments, a flashy and active deconstruction of language. But there’s a source content to Campanello’s work that goes deep and has absolute essence, and there’s an argument that challenges the reader to do the exhumer’s difficult and soul-demanding work. This book is a distressed artifact.

The final tenth of this book is a study of the word “delay,” a point that is amplified by the delayed report of the Mother and Baby Homes Commission, which was supposed to have been released this February (after one extension), and will not release its findings until early 2020. The deferral of accountability continues, remains suspended. MOTHERBABYHOME is clear and uncompromising in its keening.

Campanello herself acknowledges antecedents to her task in M. Nourbese Philip’s brilliant Zong! and in Thomas Kinsella’s Butcher’s Dozen, in honoring the voices of the unjustly dead. That is, from them, she has learned to put aside her own voice, to contend directly with the recorded voices themselves, and to cull through the officially sanctioned narratives. But it is in her indebtedness to H. D., who re-positions the poet as ritual maker, where Campanello’s considerable genius and courage come to the fore. Here, she compiles these documents and records, captures and releases all the noise among the living and the dead, and in composing upon ghostly translucent sheets, she builds a coffin and a monument. Each page is prayer. Each page is holy.

I need to say two more things.

First, the book, in its entirety, overwhelmed me. Its weight, these ghost voices and their truths, has the heft of the remains of one baby and her mother, times nearly 800. I feel that weight looking at just one page, which reads, “reverence / for / the grave / may / Dunne Patricia 25/03/1944 2 mths / derive / planting / centuries.” The grief expressed, released, is not individual, not of a single lifetime, but what will require centuries of collective work. There is no easy reconciliation.

Second, Kimberly Campanello’s steadfast commitment in this avant object is breathtaking and humbling. This is the work of a great, great artist, and of a single, attentive human being who listens with intelligent receptiveness and with full love.

Milk Glass Serenade

I cannot see what flowers are at my feet, nor you,

not yet born, your eyes and body of milk glass.

Here, let me

tell you an old saw:

A county of men filled a valley with lake, shaped

like an urn. They bestowed on it

a spillway, baptized The Glory Hole.

The surprising dark. A tunnel to the very center.

The oldest say you can see the steeple

in a dry year, impaling serous sienna.

For months, these men excised canned goods, locomotives,

the dead. Every Beware of Dog, gazebo, five-and-dime—

but left all ambitious underwater elms, which above-surface

had dropped off from Dutch elm disease.

Please become born, baby,

so I have someone to serenade. In kindness,

I’ll lie: lullabies moved from the valley,

with the children to whom they belonged.

When you lose your fresh pearl teeth

I’ll draw parallels to caverns in the hills.

And should you be unlucky enough to be beautiful,

I will tell you of the trees in this novel lake:

the forced dance, the bend

and break, trunks as carefully preserved as crow’s feet

in a wax museum grin. Trapped in line so thin, so dear

you cannot see it: the mobile of refuse, waving hello baby.

Interior

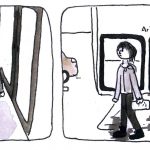

In this series Mary Tautin Moloney’s poems are inspired by and paired with photographs taken in the subway stations of New York by photographer John Moloney. The work captures the desire to connect alongside the alienation that can come with being alive; how these forces bear on one another and affect us. Mary Tautin Moloney is inspired by what she hears and observes in everyday life: the character of a place; linguistic quirks; her children and motherhood. Her collaborator, photographer John Moloney, is drawn to taking the familiar and making it unfamiliar. In both rural and urban landscapes, he plays with scale, light, and texture to create moments of seeing something for the first time. As one poem leads to the next, a journey emerges through an entirely new landscape, one of the emotional life lived. A touchstone for this project, and Tautin Moloney’s writing in general, is to “cleave to the legendary,” advice once given by Stanley Kunitz to Mark Doty. With this series, photography becomes the entry point for speaking to our larger, shared emotional existence.

bluebeard’s servants

I ran out on the sidewalk

under the broken streetlight

dry leaves chuffing overhead

like someone rubbing their palms in a black room

a muffled radio from a parked car

blue drool dribbling from its tailpipe

the green needle of the radio dial

like a knife’s edge in a dream

I heard you calling my name

like I was in trouble

like you were right there beside me

with an unwashed cup in your hand

but I knew you weren’t outside

I watched you leave the yard

barefoot in your robe of fireflies

I knew the house was empty

the lukewarm sleeping flank of the drier

the dishwasher’s matted pelt

the long black velvet box of the hall

blood on the keys

I was always the child who had to look

who went in the study with the torn chairs and stuffed birds

who upended the trinket box and found your fob

my breath rattling in my throat like bones shaking in a dice cup

I saw the hot coil a carful of blue smoke

why didn’t the driver help me

Mother shrugged as you led me away

to the inevitable chamber

where dead girls moulder in velvet gowns

locked in like wives

Pushing against the Familiar

Termination Shocks by Janice Margolis

University of Massachusetts Press, 2019

Paperback, 258 pages, $13

Famous Children and Famished Adults by Evelyn Hampton

FC2, 2019

Paperback, 160 pages, $13

Sooner or Later Everything Falls into the Sea by Sarah Pinsker

Small Beer Press, 2019

Paperback, 288 pages, $17

There is a familiar and sort of empty phrase that we come across from time to time in blurbs and reviews. This book left me wanting more. It’s an odd notion. Applied to novels, it’s essentially unfathomable: what more could be asked of Moby-Dick—Ishmael’s intervening years? Or Invisible Man: do we need “Part 2: Still Down Here in the Coal Bin”? Perhaps, while only seeming to laud, the critic-reviewer is giving a sneaky backhand, and that I want more actually implies there’s not enough here.

Maybe when applied to collections of short stories and poems, the phrase “this book left me wanting more” has somewhat sturdier—if still wobbly—legs. Perhaps the reader–critic enjoys the author’s use of language or metaphor so greatly that reading even more would simply be lovely . . . so, really, all that’s happened is that the critic–reader has tapped into his pleasure principle. Or maybe it’s something else; maybe it’s the setting of the scenes or the fascinating characters that entrance our reader–critic: a bit dulled by his own daily life spent watching baseball and eating Doritos, he’d prefer to linger in the well-imagined fictional setting, in a space richer and with people more interesting than those in his own poor surroundings. But if that’s the case, it’s not so much that the critic–reader wants more of the book—the poor fella just wants less of his current existence.

Left me wanting more. When describing authors’ first books, it takes on even trickier meaning (because if we don’t want more now . . .). As luck would have it, under review here are three such debuts: Termination Shocks by Janice Margolis, Famous Children and Famished Adults by Evelyn Hampton, and Sooner or Later Everything Falls into the Sea by Sarah Pinsker. Having read all three, I can honestly say one thing. I want more.

Quick admission: a few years ago, a collection of mine received the Juniper Prize. While Termination Shocks has also received the Juniper Prize, I don’t know Janice Margolis, and my current ties to UMass Press are more or less non-existent. That’s not a complaint, just a fact. UMass is an academic press, and it doesn’t have the family feel that many literary presses strive for. My point is that there’s no conflict of interest in my discussion of Termination Shocks.

I began Termination Shocks with hopeful anticipation. Here was a book chosen for its prize by Sabina Murray, a talented writer interested in language, tone, and structure. And the book begins strong—the first of its five stories, “21 Days,” is impressive in its reach. The story is a feverish first-person history of Liberia as told through the point of view of an orphan stuck in her family hut for Ebola quarantine in the days following the death of her mother. The title refers to the length of her quarantine, and the story foregrounds language, form, and meaning (social commentary) over plot and even characterization. Here a rat has as complex a characterization as the narrator’s romantic interest, or her teacher, or her mother (it’s a cool rat). Margolis relays the narrator’s experience cleanly and beautifully:

Everything crackles inside me. I could be made of lightning. A dying bird beats against my brain, swoops between my ears, pecking songs Mama sang me. It makes the notes bleed between my legs, and I cut the gold-and-green dress into beautiful rags to catch the falling sounds.

Of course, the situation Margolis has chosen to write about is one of intensity, sorrow, and fear, and the narrator’s feverish reveries lead to wonderfully revelatory moments, such as, “[My teacher] tells me how animals groom each other in the most vulnerable positions. How humans groom each other with language. Miss Browne grooms me for hours.”

“21 Days” is a beautiful work. And it does raise questions of appropriation, too—a white American author writing about a Liberian girl possibly stricken with Ebola. But to my reading, the story seeks authenticity, and it tries to dramatize the moment in brutality more than in beauty; the only villains are, if anyone, the white medical staff. It’s a challenging story to read and a challenging story to write, and credit goes to Margolis for taking the challenge on.

After “21 Days,” I read the second story in the collection, “Being Tom Waits.” This is a story narrated by a person who has become Tom Waits. I know very little about Tom Waits. He seems to need a shave. And I like the song about Singapore. But I also feel that what I enjoy about Tom Waits is not what fans of Tom Waits enjoy. This did not interfere with my enjoyment of the story. If you want to read a story version of Being John Malkovich transferred to the mind of Mr. Waits, here you go, minus the scheming plot. We are immersed fully in the head of the fictional Tom Waits. The story is plotless, but no matter—it’s funny, irreverent, referential, absurd, and loving:

Speaking of Normal Mailer, he and I had a brief correspondence in the ’70s. For some reason, a fan letter I’d written gave him the impression I was a tall dirty blonde. I didn’t disabuse him of his mistake, and allowed a non-existent part of my body to be described in a particularly lascivious exchange he later insisted was meant for Gloria Steinem. As requested, I destroyed the letter, which, as a lover of history, I deeply regret.

Incidentally, am I the only one who notices that incessant ringing?

The story veers between confused recollection, wanderings of Los Angeles, Waits’s frustrations, paranoias, conceptual albums, lost genitals, and more. Between it and “21 Days,” my expectations for the final three stories in Termination Shocks were considerable, but the returns diminish a bit. The fourth story in the collection is narrated by the Berlin Wall, an interesting concept that becomes a bit static (and very removed from the present day). The concluding title story is another structural experiment, wedding the stages of rocket liftoff with personal relationships; by the story’s end, the design feels more scattered than accumulative. The collection’s middle story, “Little Prisoners,” is an interesting outlier: a 170-page novel-length piece written as straight realism, even as historical fiction, following an archaeology student in Syria who falls in with government protesters and becomes accused of spying, which leads ultimately to a big reveal about her past.

Termination Shocks is an odd collection that creates, at its best, wonderful literature. It features two challenging, strange stories—one risky and rewarding, and the other inanely effusive and immersive. While the final two stories also lean toward innovation—of structure, of concept—they, and certainly the very long “Little Prisoners,” don’t quite match the sheer ambition and exuberance in the first two pieces. It’s fair to say that the collection left me wanting more.

In her debut Famous Children and Famished Adults, recipient of the FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovation Fiction Prize, Evelyn Hampton includes quite a few stories: twenty-two that collectively span just 160 pages. Given the stories’ relative brevity, it’s only logical that this is a very different book from Termination Shocks, especially in terms of the foregrounded fiction elements. Rather than progressive narrative tensions (“plot” is a four-letter word here), or characters existing over long periods of time feeling the deep impacts of upsetting life events, the stories in Famous Children and Famished Adults are swifter, stranger, and more concerned with language and the mindsets of their many strong-voiced narrators. These stories are elusive in terms of being plot-reducible; that the collection was chosen as FC2’s Sukenick prize-winner by Flournoy Holland is no surprise, since she is a writer as much immersed in mood and the line and deep evocations of point of view as anything else. Hampton’s fiction seems very Holland’s type of fiction.

Which is great. It leads to the publication of stories like Hampton’s, works that push against the familiar. It’s hard to group the collection: these are stories as glimpses, hints at strange characters in stranger relationships—and we’re only ducking in to watch them a few moments. This is seen often, in stories such as “Choo and Cream” (a couple joined together by a “a nearly transparent child who clapped its hands not out of glee or approval, but because of the awkward way its body was dangling”); “The End of History” (a nameless female narrator “wants to discover . . . a framework for her content”); “Every Day an Epic” (among other things, we learn that the narrator has “been looking at the world through a lens,” enters into it, and “open[s] intervals and unravel[s] across them”); and many more.

There’s a slightly tendency in Famous Children and Famished Adults toward the surreal parable in metaphorical situations that explore more mundane experiences (“Choo and Cream” could be read as a metaphorical description of what it’s like to have a newborn). But even that tendency isn’t very pronounced; more than anything, it’s easier to say what isn’t in the collection. Throughout, Hampton shows an impatience for context and clarity, which makes the normal experience of fiction—enjoyment, emotional impact—a bit hard to come by. One piece, “At the Center of the Wasp,” goes thusly: someone who bottled and sold scents has died; there’s an island that is either literally or figuratively made of shit; the dead person has to be buried; the narrator doing the burying (and complaining all the while about the shit and the island and the smell and burying) is related to the dead person. The story is an effusion of frustration with context barely provided; it’s like stepping onto an elevator with a person on a cell phone engaged in a furious conversation you cannot quite piece together. Which can be enjoyable and meaningful, especially if you sit back and enjoy the lines, the point of view, the strangeness.

“At the Center of the Wasp” lies at the far end of the collection; most of the stories have a bit more clarity, and the strangeness shines rather than muddies. In “Cell Fish,” the narrator learns that her significant other is dying, and Hampton tells this story through elision rather than a more predictable head-on style. Her patience and ability to let white space do work is admirable, as is her ability to let small gestures convey tone, character, emotion: “The doctor pressed her fingers together, enclosing the space in front of her face. When she spoke, the voice seemed to come from the space enclosed by her hands.” Rather than pursuing the story into the territory we might generally expect—hospitals, progression of disease, the impact on day-to-day life—Hampton more often keeps us caught in the impending doom rather than stepping into the more familiar literary ground of the doom itself. This is a harder task; with most writers, it’s not intuitive. That Hampton prefers in her fiction to move us into—and to remain in—those quiet spaces before the dam breaks is impressive and admirable.

A great thing about story collections is that they rest on their strongest pieces. For me, the greatest works in Famous Children and Famished Adults are the ones that, perhaps begrudgingly, do allow more narrative context. A bit of familiarity, for me, makes strangeness even stranger, as it allows situation, voice, and language to become more uncanny rather than entirely uprooting the reader. The story “Jay” is the easiest example: the narrator’s friend, a possible spy, has vanished from her life, and we see the impact of the two’s strange interactions play out over a longer period of time. Other stories, too, give us more context: “Fishmaker,” “Cell Fish,” “The Slow Man,” “Since All the Cats have Vanished,” for instance, let the reader in a bit more and so, at least for me, have greater impact. At its best, Famous Children and Famished Adults is a successful, unique, and commanding collection, though sometimes it’d be nice to get a larger picture of a given story’s disaster, a larger sense for how it plays out on the characters’ lives. Just a little more.

Sarah Pinsker’s debut, Sooner or Later Everything Falls into the Sea, is less like the other two collections here under review. Foremost, it’s not a contest winner chosen by an academia-established literary author; rather, it’s published by Small Beer Press, an indie known for works that, while literary, lean toward the fantastic. It’s no surprise that the stories in Sooner or Later Everything Falls into the Sea were previously published in genre-aligned journals including Asimov’s Science Fiction and Lightspeed. While Hampton and Margolis certainly feature experimental-leaning fictions, their works are, at least to me, a more familiar type of literary experimentation—more academic than commercial.

I opened Sooner or Later Everything Falls into the Sea with a feeling I had when I was much younger and reading books not as a writer but simply as a reader, with no expectations, no hopes or skepticisms, no begrudging or apprehension. Pinsker’s stories only magnified my childlike sense of excitement and wonder: the worlds they contain are imaginative, vivid, and well-designed, almost like Cornell boxes—vividly adorned and other-worldly while still being tilted versions of our own. “A Stretch of Highway Two Lanes Wide,” about a young man who loses an arm in a work accident, sadly and poignantly captures the longing, interestingly, of his replacement robotic arm:

It didn’t just want to be a road. It knew it was one. Specifically, a stretch of asphalt two lanes wide, ninety-seven kilometers long, in eastern Colorado. A stretch that could see all the way to the mountains, but was content not to reach them. Cattleguards on either side, barbed wire, grassland.

Other stories throughout the collection twin the surreal with the poignant ordinary. “Remembery Day” features an annual parade for military veterans; the twist is that on this day, the veterans vote whether or not to lift their “Veil,” a perpetual forgetting of their war traumas. In “No Lonely Seafarer,” a genderless narrator confronts sirens who have laid waste to a town’s shipping industry. “Wind Will Rove” asserts the need for people to hang onto the seemingly unimportant textures of their shared history—especially while stuck on a spaceship adrift in the universe. The title story features a scavenger who finds a woman stranded ashore in a boat; we learn from a slightly unwieldy narrative style that the lost woman was living, as many do in the story’s world, on a cruise ship, playing bass in a house band that exists to entertain the privileged wealthy. In the quietude of the scavenger’s abode, we see a collision between consumerism (the musician) and being a hermit (the scavenger), between a life of accumulation and a life, if lacking in material things, more attentively lived.

The stories in Sooner or Later Everything Falls into the Sea remind me in style, tone, and world-construction of the stories collected in Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man; this is true of their thematic underpinnings, as well. If Evelyn Hampton’s stories lean toward the parable, Pinsker’s don’t lean so much as announce meaning via loudspeaker. As with Bradbury’s, these are message-driven works of fiction. Their intricate architectures are often overlaid onto moralistic messages, and at times this serves to reduce the stories’ emotional valence. There are cautioning moments, as well. “The Low Hum of Her” is implicitly a Holocaust story in which a father has built for his daughter a replacement robotic grandmother; this story, too, is poignant, as the daughter begrudgingly comes to love the robot, but as the story doesn’t once mention the horrible sufferings of the Holocaust, the fraught setting seems almost whimsically chosen.

Of course these aren’t boxes—they’re stories, ranging from as brief as three to as long as forty-plus pages. But to carry the Cornell comparison further, as with the artist’s famous boxes, the stories in Sooner or Later Everything Falls into the Sea rely on the reader to infer from or project emotional complexity upon their dazzling arrangements, and as we gaze at the design elements, some of the more literary elements—especially character complexity—get shorter shrift. For a debut collection, Sooner or Later shows remarkable promise—if only the real complex human stuff of it were given a little more attention.

One last side-note: while these three collections are very diverse in terms of form and craft, it’s important to observe diversity of both voice and represented experience, as well. Other than “21 Days,” I’m not sure these collections are expanding diversity in those ways. These are three very white collections, very middle class. That’s just an observation, not a criticism. Of course, writers can only write best what writers can only write best, and Janice Margolis, Evelyn Hampton, and Sarah Pinsker are writing awfully damn good fiction. There is plenty here—plenty to admire, to envy, and to praise. These three collections are pushing against the ordinary, pushing against the familiar (if imaginary) line that wraps neatly around what fiction, what literary fiction, should be.

And they should be pushing against that line; they should be pushing against any expectations. That’s what we should expect from these books given to us by such innovative and important presses. While the reader–critic in me thinks, I really hope Pinsker/Hampton/Margolis goes out now and writes a greater novel with more emotional impact, the teacher–writer part of me rolls his eyes and disagrees. Shut up, critic–reader. To hell with your notion that fiction should conform to your expectations. You’re not in charge. They are, these three talented authors. Let them keep on doing their work. They’re doing a great job—well more than enough.

The Mother, the Bee, the River’s Edge: A Story from The Kalevala

This comic strip is an adaptation of part of the first Lemminkäinen cycle in the Finnish epic, The Kalevala. The Kalevala is an adaptation of the oral folklore of Karelia and Finland written by Elias Lönnrot and is considered a major cornerstone of Finnish identity and culture. I started reading The Kalevala to get a better context for some of the metal music I listened to and found myself drawn to the women in these narratives. To me, they were as interesting (if not more so) than the male heroes. Lemminkäinen’s mother, in particular, is my favorite character, despite not being given a name herself. In this comic, I hoped to capture her own heroic journey and how her son’s happy ending did not necessarily lead to her own.

Not Enough

I Live in Grandma’s Kitchen

I live in Grandma’s kitchen. The walls are the blue and white she painted them a few years ago. The cabinets have the tiny white knobs I reached for when I learned to walk. Through the window above the deep sink, tonight’s overcast sky creeps its way over the setting sun and into the chilled gray room.

While pouring a bag of beans in a pot to boil, and before I grab a jalapeno and cut an onion in half so that I’m just on the verge of tears, I hear Grandma yell from the living room.

Don’t be dumb, you’re making them wrong. Rinse the beans before you boil.

I stop what I’m doing and rinse them or else she’ll make me keep doing this until I do it the right way.

—

I’m washing the dishes. They’re all perfectly matching, off-white and no chip in sight, except for one plate. It’s brown, bigger than all the rest, and has this sketch of a cottage in winter on the face of it. It’s the only one she will eat off of. It’s covered in the remnants of food that she didn’t end up finishing off with her tortilla. The little cottage’s windows are coated in the marks of beans refried with Manteca. As I rinse off the plate, with the rough side of the small yellow and green sponge, I see the windows open and the snow-covered photo pop amongst the sea of off-white in the silver sink. The dishwasher is full. I bully around the bowls, shift the silverware, and arrange the cups so that I can fit this one last dish in before I pour the detergent and finish off the sink with my pruned fingertips. Scouring for something sweet after dinner, I hear her shout from the pantry.

That’s not how you’re supposed to wash dishes. If you break a plate or my washer, you’re going to pay for it.

I pull out her dish and wash it by hand. It is her favorite.

—

I fill a bucket with Clorox. I feel the bleach burning the insides of my nose as it swims with the tiny bit of hot water and soap. I push all the kitchen chairs into another room, pick up the mat from the sterile grey linoleum and sweep away the red-brown pine needles I tracked in after school with my boots. The mop slushes around in the suds as it prepares to douse the floors. I roll up my jeans to avoid the splash the little gray braids will make when they hit the floor. I will feel the warm water underneath my now bare feet and move my way from one corner of the kitchen where the cabinets meet the wall, all the way to the tiny forgotten space where the refrigerator just barely misses touching the ivory-colored baseboard. From the TV room, I hear the sounds of her Mexican soaps go silent.

Stop being lazy. Just scrub the floors on your hands and knees.

I listen because I’m tired.

—

I turn off all the overhead kitchen lights but keep the dim stove-top light on. I rest. The kitchen table is small, tan, and the chairs have no cushions on them. The hard oak starts to hurt if you sit for too long, but it feels better than standing does right now. I sigh and pitter my fingers, reaching for an orange in a basket to squeeze and play with so that I don’t need to think anymore. The hall out of the kitchen is dark, but I can make her figure out, shuffling to bed, dragging her slippers on the dark, plush carpet. With her hands stuffed warmly in her robe, ready for bed, she says.

It was all delicious. Good job, Mijo.

I smile and tell her I love her because… well, because.

—

Now I’m sitting here, and I finally have nothing to do. The food is all done, the dishes are dry, and the floor is sparkling in the tiny bit of light that’s left in the room. I ask her what to do now, but there’s no response because hospice came and took back their oxygen machine, the shelves of her medicine cabinet are free of pills, and a bottle of Chanel is sitting on her vanity unmoved for four years now. Now all I do is live here in her kitchen and wait for her to yell again.

Interview: Charles Simic

A Serbian-American poet and former co-poetry editor of the Paris Review, Charles Simic was born in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, and immigrated to the United States in 1954 and started publishing poems by the age of twenty-one, around 1959. He earned his bachelor’s degree from New York University in 1967, and within the year published his first full-length collection, What the Grass Says. He has since published more than sixty books in the United States and abroad along with numerous translations of French, Serbian, Croatian, Macedonian, and Slovenian poetry. He is the author of several books of essays and has edited several anthologies. He has won numerous awards, among them a MacArthur Fellowship and the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1990 for The World Doesn’t End. He was poet laureate of the US from 2007 to 2008.

Simic has taught American literature and creative writing at the University of New Hampshire since 1973 and is now professor emeritus there. The following conversation took place at the Miami Book Fair shortly after the publication of Scribbled in the Dark (Ecco, 2017).

Judith Roney for The Florida Review:

When your family first moved to the US, they settled in Chicago? I felt a connection to that because was born and raised in Hyde Park, Chicago.

Charles Simic:

Actually, it was New York, then Chicago, in Oak Park. We moved because my father’s job had moved to Chicago. I finished high school in Oak Park, then my parents broke up. I left home and was on my own, and got a job in the city on the Near North Side. Then I picked up and went to New York City.

After that, I came back to Chicago, but the family had fallen apart, and there was no money, so first I worked during the day at the Chicago Sun-Times. Not a fancy job, just a lowly job. I started going to school at night, at the University of Chicago. It took a couple of years because there weren’t too many courses at night, but it was an interesting time. I lived on the Near North Side because that’s where the Chicago Sun-Times was, by the Chicago River, so I’d go off to work, finish, then have to catch the . . .

TFR:

The L?

Simic:

Yes! The L train! You know, you’d go down south, to Hyde Park where the university was, and it was a different world there, in Hyde Park. And I was just saying to someone last night how Anglophiled it was at University of Chicago—all the professors wore tweeds and affected a British accent—even though they were born in Wisconsin or wherever.

TFR:

So, they put on fake accents?

Simic:

Yes, yes. And they would say to you, “Charles, if you like poetry, you must read Andrew Marvell.” And I’d say, “Sure, sure.”

(laughter)

TFR:

I’ve lived in Florida for nearly two decades now, but when I started in on the poems of section two in Scribbled in the Dark, the images grabbed me and took me back to my childhood. There’s “Bare Trees,” “January,” “In the Snow,” and “The Night and the Cold,” so many northern images that I felt I was back in wintertime Chicago. It was “Bare Trees” that reminded me of my lost period after high school when I wanted to attend the University but didn’t understand the process. I would go walk the grounds, wander the Oriental Institute, and just hope someone would ask, “Hi, want to take a class?” If I may, can I read you the lines that I felt the speaker was addressing me quite personally?

Simic:

Sure!

TFR:

“The bare branches moving in it, / Are like the fingers of the blind / Reaching to touch the face of someone / Who’s been calling out to them / In the voice of geese flying over, / The shots of a hunting rifle, / And a dog barking outside a trailer / For someone to hurry and let him in.”

Thank you for those words, I mean, yeah, that’s what it was like for me at nineteen.

On a larger subject, I’d like your opinion about the so-called state of poetry in the United States today.

Simic:

In the US there is more poetry being written than in the rest of the world put together. It’s an amazing, amazing thing. There isn’t a huge audience for poetry, but the number of poets now writing compared to when I started out in the fifties and mid-fifties has grown huge. I mean, in the city of Chicago, we knew the aspiring poets and contemporary poets. We knew about Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, and all the others. I would say there were fifteen to twenty at a given time. It was like a cult!

Everybody was interested in literature, mostly fiction, of course, and not just American but European modern fiction as well. But poetry, well it was really an activity that was marginal, especially in Chicago—always like it had a chip on its shoulder culturally.

(laughter)

TFR:

That’s a colorful way to put it. I’m thinking of [Carl] Sandburg’s description in his poem “Chicago”—“the City of Big Shoulders.”

Simic:

It was such a small poetry community for a while, but then the Beats were the ones who made a big difference. It started with giving free poetry readings with [Allen] Ginsberg and everybody else. They were very, very popular. Then they were at colleges and universities giving readings, and a whole generation discovered this was a lot of fun! Both students and adults showed up to readings, so they started this thing in the sixties, and all of a sudden it caught on. I know my generation of poets profited from this—we were getting invitations from all across the country to come read. This was followed by the beginning of writing programs.

TFR:

Aaah, and now we have the “explosion” of writing programs.

Simic:

Yes, yes. They keep turning out poets. So you see, it’s really impossible to get a clear picture of what’s going on. There was a time until about ten to fifteen years ago, when someone like me who was real passionate about poetry, and others who were passionate, could get a clear idea who the poets of the generation were, even by region, East Coast, West Coast, etc. But now, with the proliferation of poetry on the Internet—I mean, you used to go to bookstores to find out about new poems and poets! There were so many everywhere, each town had a bookstore, and you went to the poetry section, and you could see who was doing what. Sure books are still coming out, but not so easily displayed. They aren’t as “seen.” So now, as I say, it’s beyond anyone’s ability to answer confidently where poetry is going.

TFR:

Tell me your thoughts on something I heard on NPR. It was a comment on poetry, and how in Europe three to four hundred will gather for a reading, but in the US only a few dozen.

Simic:

No, that’s not true.

TFR:

I’m glad to hear it!

Simic:

Years ago, in Russia, when poetry was read, there used to be a lot of people, in Paris maybe a few more, in Germany a little better, and in Spain even more, but here in the United States, there are readings even in remote areas at state universities, in the Dakotas, in Oklahoma, and Kansas. Perhaps because there’s not as much to do, as many activities all the time, they’ll have a poetry series each year which they alternate with fiction, and anyone with respect for literature will come and listen. Hundreds show up! Now, in New York City there’s too many other things going on, so only a few dozen may attend. And now, more recently, it’s just impossible to tell. There’s live reading groups online, and YouTube readings. It’s just impossible to grasp.

TFR:

I wonder, in hindsight, what will we see? I mean, as far as schools of poetry, movements of poetry, eras of poetry. We had the Symbolists, the Modernists, the Black Mountain Poets, and as you mentioned the Beats. What will this era be called, if anything? The Onliners? The Techs? My students go to poetry slams, and most participate, too. That’s kept poetry vibrant for them. I just wonder what this era will be—there’s a lot of political and social justice work out there bringing awareness to the art. Poetry still has a job to do.

Simic:

Yes, yes.

TFR:

Let’s get back to Scribbled in the Dark. When I read the title poem, I knew I wanted to ask you about it.

Simic:

This is a kind of big city experience in this poem. Up until a few years ago, I used to teach at both the University of New Hampshire and NYU, which gave me an apartment. One summer night, late, the Village is full of people, it’s 3:00 a.m., and I hear shrieks in the street, and I wonder, is it joy or fear? Is someone arguing? It could be anything! So I’m in bed, and I get up and look down at the street because it’s dark, and I’m up then—you see, I’m an insomniac, so was my father, it runs in my family, but it’s no big deal, and so if I lie there in the dark I get rest to a degree but no sleep. But, if I turn on the lights it feels like a struggle. And if I have an idea that comes to me, I don’t want to turn on the lights, but I can’t help myself, I have to write the idea down, so there I am, scribbling in the dark, but (laughs), often it’s quite hard to read what I wrote in the morning. But it works—I’ve been doing this for years, because, you know, you’ll forget in the morning.

TFR:

I love that.

Your poem “The White Cat,” where you say “the one who disappeared,” is profound to read.

Simic:

That’s actually kind of a true story.

I’ve lived in a little village in New Hampshire for forty-five years, and I know all my neighbors, a long time, and you get to know each other, and get to chatting, and someday someone says, “I wondered what happened to so-and-so,” and that’s how it starts.

TFR:

It resonates. I like your line, too, “my childhood, a silent movie.” What a metaphor.

Simic:

This was in my childhood in Belgrade. They were still showing silent films. My grandmother and mom would take me, and I’d fall asleep. My mother would nudge me and wake me up during a scene and say, “Look, look, a horsey!” And I’d say “Horsey!” The city was occupied then, and we had a curfew. We had to be home by 10:00 p.m. or we could end up in a camp.

TFR:

Wow. That’s experience, and your experience is, of course, unique, but it’s the commonalities that fascinate me, that span generations, that are ageless. I was raised by my grandmother, who was born in 1892, and she played the piano at the local theater playing silent movies when she was a young girl. We’re still those children, aren’t we? We remember so much.

Simic:

If you want to have a perfect memory of childhood, I don’t know, I had bombs falling all around and worried they’d fall on my head. It wasn’t perfect.

TFR:

I know. As instructors we joke “no one wants to read a happy story.” Some dark material makes the best poetry. I want you to know that I mention two quotes of yours at the beginning of all my poetry course sections.

Simic:

Yes?

TFR:

The two that I always refer to are “Don’t tell the readers what they already know about life” and “Don’t assume you’re the only one in the world who suffers.” I hear these two when working on my own writing, every time, and students struggle so with these concepts.

Simic:

You must out-write yourself. You have to find the way to make it interesting for the reader. You can’t say it in the same old way. You must work to captivate the reader.

The Strangers

The day of his daughter’s arrival, Daniel cut back the Marilyn Monroes. He’d pruned them every January for the past ten years. The roses were a true victory—he’d been called a gambling man by a horticulturist who warned Daniel he wouldn’t be able to keep Marilyn Monroes alive. They were too finicky, they required a frost in the winter and the temperature didn’t drop low enough in Tampa. But Daniel knew he could keep any plant alive.

Daniel wasn’t sure why Hayley was coming home. Hayley’s email had said: “I want to say goodbye to the house.” Why? How was it possible to tell a house goodbye? If his wife, Olivia, had still been alive, she would’ve explained it.

The house was packed, and the movers would be there the following week. Daniel had already shipped most of Hayley’s belongings to Los Angeles. Daniel knew never to throw away anything Hayley owned. When she was a little girl, Daniel had made the mistake of throwing away a headless Barbie he found by the pool, and Hayley grieved the loss of the doll for weeks. Olivia had been livid. She’d called him heartless and ordered him to never touch his daughter’s possessions again. For Daniel, objects had little history or future. He couldn’t understand why Hayley and his wife had gotten so upset. But Daniel remembered Barbie when it came time to pack up Hayley’s things. He tossed everything from her room into boxes without examination. Just a few packages remained to be sent to her in California.

He finished tidying the roses. There was still enough time for a Gatorade and a shower before Hayley arrived. He’d just stepped into his bedroom when there was a loud knock at the door. He found his daughter on his steps. It was the first time she’d been home since his wife’s death a year back. She smiled up at him.

“Hello, Daddy,” she said, shyly.

Despite the fact he knew nothing about her—favorite color, movie, food—still, his chest grew warm at her smile. The same smile she’d had all her life. He was shocked by how much he wanted to pull her to him. He remembered the satiny feel of her skin when she was an infant, the way she’d kicked her feet when he said her name.

“I got on an earlier flight,” she said. “I tried to call you.”

Damn iPhone. Since his retirement, he forgot to even turn it on.

“It’s so weird here,” Hayley said, her voice an echo in the cavernous dining room. Olivia had wanted the drafty old house. Daniel couldn’t wait to sell it.

“Do you really want to move?” Hayley asked, trailing a finger across the top of the buffet, the only piece of furniture he was keeping because it had been his grandmother’s. When she looked at him again, the smile from the doorway had disappeared. There were dark circles under her eyes, creases on her forehead. How old would she be now? He did the math. Born the year he’d made partner. She’d be forty in June. There were small patches of grey at her temples, her hair the color of chestnuts now instead of purple.

“I don’t need the space now that it’s just me,” he said.

“It’s so weird without Mom,” she said. “Isn’t it weird?”

It had been. For a little while. No rattle of Olivia’s old Mercedes. No smell of lemon in the morning. Now it felt normal. And good. Of course, he couldn’t say he didn’t miss Hayley’s mother, that he realized at sixty-seven he’d never been in love, and probably never would be.

He said, “Yes. Very weird.”

“I’d like to lie down,” she said. “Long flight.”

He’d left her twin bed in her room, and he led her there.

“I’ll be up in a few hours,” she said.

—

He ate at the deli for most meals now and his cabinets and fridge were bare. While Hayley slept, Daniel went to the grocery store and stocked up on all the things Olivia kept around: Stouffer’s frozen lasagna, bananas, whole wheat bread, butter, coffee. He remembered Hayley eating a cereal called Lucky Charms, so he bought a couple of boxes, happy that he remembered one thing about his daughter.

At just after seven that evening, Daniel knocked on her door. He’d heated up a lasagna, and it was getting cold. Hayley didn’t answer and, when he poked his head in the room, she said she needed to keep sleeping, that she’d had a “rough few weeks.” Should he ask her if anything was wrong? Was sleeping a bad sign?

On one of her last days in the hospital, Olivia grabbed him by the wrist and pulled him to her. So close he could see the red veins intersecting the whites of her eyes. This was the closest they’d been in many years.

“Promise you’ll talk to Hayley. She’s in a bad way.”

Daniel hadn’t been able to tell she was in a bad way. In fact, he hadn’t seen her looking so good in years. No purple hair, no bitten fingernails. The way she looked, it was hard to believe she was mentally ill, though Daniel wrote a check for $2400 every month to pay for her therapy.

When had his daughter become bipolar? It made his jaw clench to remember the promise Hayley had possessed—acting lessons, school plays, her declarations that she wanted to be the next Nicole Kidman. And she’d been so pleasant—squealing with laughter when he chased her in the pool, making up dances, using the cabana as her stage.

Since Olivia’s death, Hayley had called once a month, always on a Sunday night. They talked about rain. The lack of it in Los Angeles, so much in Tampa. If Olivia were around, she’d ask Hayley questions: Are you taking your meds? Going to bed at a reasonable hour? Working? But she had the right to ask. Daniel didn’t ask questions. What would he do if Hayley gave him answers he didn’t understand? Olivia and Hayley had their own secret language. Olivia bought a ‘best friends’ necklace and gave Hayley the ‘best’ half for her tenth birthday. The one time Daniel wondered if Hayley should have friends her own age, Olivia’s eyes filled with tears.

“My daughter is here for me. Which is more than I can say for you. You’re a stranger to us.”

No, Daniel would let Hayley sleep. He would leave her alone.

—

Just after eleven the next morning, Daniel heard the click of her doorknob. He was at the sink, rinsing a bowl when she padded into the kitchen. Bare feet, wearing a faded blue T-shirt and a pair of jeans. Her hair stuck out in a million directions. She looked the way she had in high school, after a night dancing, her hair reeking of smoke, making him wonder why he was spending thirty thousand a year on private school when she partied with the public schoolers and brought home Cs.

They said “good morning,” and he gestured to the box of cereal on the table.

“Your favorite, right?”

She smiled. “I don’t eat sugar anymore.”

Hayley grabbed a bottle of water from the counter and picked up a banana from the bowl. He waited for her to say something else. She didn’t. She left the room and, a few minutes later, he looked into the backyard to find her sitting beside the drained pool, her legs pulled up against her chest. The half-eaten banana was by her side. Her face was turned away. Was she saying goodbye to the pool?

After a few minutes, Hayley stood and went over to the steps. She walked into the empty concrete basin. She walked to the center and then stared up at the sky. Daniel craned his neck and looked up, too. Seagulls, a whole flock of them, flew in a V shape across the sky. A memory: feeding bread to the seagulls with Hayley when Hayley was a child. Hayley loved to chase the birds, and he had laughed and encouraged her to run faster. There had been good times. A few of them. Daniel considered walking out to the pool, bringing the loaf of bread with him. But Hayley might want to be alone. She might’ve come home for the peace she never got when his wife was around.

When Hayley came home for Christmas, Olivia made sure they had a packed calendar: ringing the bell for the Salvation Army outside of Publix, a carol sing-a-long at the nursing home.

“The worst thing she can have is quiet,” Olivia always explained. “I must keep her busy so she doesn’t focus on her sadness.”

But what if this wasn’t true? What if peace was exactly what Hayley needed? Daniel had been to Los Angeles once, and the traffic and smog had been as much of a shock as the coffee shop where Hayley worked, a den of tattooed and pierced people who huddled over laptops all day. Didn’t people in LA work? Why weren’t they at offices?

A few minutes later Hayley came in the house. He walked to her room. She sat on her twin bed, her back to him. He thought he saw her shoulders shaking.

“The new people are going to fill the pool in,” he said. “I had to drain it.”

“You never used it anyway,” Hayley said. “Mom and I were the only ones who ever went in.”

The cold tone of her voice was a shock. Better to give her space. Daniel shut the door.

Hayley didn’t come out again until dinner. He heated up another lasagna, and they ate it on paper plates. The only sound was when he blew on the noodles. After they finished, he asked her if she’d like to go for banana splits, a peace offering since she’d sounded angry about the pool.

“No sugar,” she said, eyes glued to her plate. “Remember?”

She picked up her iPhone and began typing, probably a text about what an idiot he was. Daniel cleared the table.

—

The next day Hayley sat out by the pool again. For hours. When it rained, she sat under the awning. He thought he saw her crying, but he couldn’t be sure. He wished his roses were still blooming. He could’ve shown her each one. She’d liked the garden a long time ago. She’d helped him add just enough aluminum sulfate to the soil to turn the hydrangeas blue. Seagulls, ice cream, flowers. The memories served as proof there’d been times when he knew things about Hayley. If only he’d tried harder, they could’ve been closer. But when Olivia was alive, it was like she and Hayley were the only people in the house. His presence was more like a shadow, lurking, ready to be dismissed, a stranger indeed.

Daniel took a nap and woke just before dinnertime. Hayley wasn’t in the backyard and she wasn’t in the kitchen. The door to her room was closed. He heard talking. He walked past, not wanting to disturb her, not wanting to eavesdrop. But what if something was really wrong with his daughter? What if her trip home was a cry for help? Was he being too dramatic?

He tiptoed back down the hall and pressed his ear against Hayley’s door. Murmuring.

He couldn’t make out words. But then: “I burned all those bridges,” Hayley said, shrill enough that he could make out each word. “I have nothing to go back to in California.” A cry. A moan.

Daniel gritted his teeth. He retreated into the darkness of the hallway, to his bedroom. He didn’t sleep for hours. He kept hearing his daughter’s words. “I have nothing to go back to in California,” she’d said. What did that mean? Had someone broken her heart? Had she lost her job? Who was on the other end of the call? He wished he could contact that person and get the story. Asking Hayley about it felt impossible.

He pictured her apartment in Los Angeles, the one time he’d been. The cactus in the windowsill. She explained it bloomed at Christmas. He’d taken her to the local nursery and bought her more cacti. “They don’t need much attention,” she’d explained. “I can always keep them alive.”

He’d thought that was weird then, another way they were different, another way he didn’t understand his daughter. Daniel loved that his roses needed him. They depended on him for water and food. They flourished under his care. Hayley and Olivia hadn’t flourished under his care. Olivia told him no amount of money could ever make up for the fact that he never laughed at her jokes, that he didn’t appreciate her thoughtfulness.

One Valentine’s Day she bought candy apples etched with hearts for him to bring to the office. Whoever heard of a grown man, the head of a law firm, bringing in candy apples for his employees, the same employees who were supposed to be terrified of asking him for time off at Christmas? He said he wouldn’t bring them in, and, one by one, over the next few weeks, Olivia ate the apples, crunching loudly, glaring at him.

Olivia wasn’t thoughtful. She wasn’t kind. But maybe she was right about their daughter. Maybe Hayley was in a bad way. But what could he do?

—

Sometimes, when clients were in town from far away, he took them to Palm Valley Fish Camp because the restaurant was famous for its fried shrimp. Would Hayley like fried shrimp?

He knocked on her door the next morning and, when she opened it, he suggested the dinner nervously. He expected by her swollen eyes that she would say no. But to his surprise, her face lit up the way it had when she saw him the night she arrived.

They decided on seven, and twenty minutes before she walked down the hallway wearing a cherry red dress with a puffy skirt and shiny black high heels. An outfit too fancy for Palm Valley Fish Camp, which was out by the marsh, and a place where the staff looked the other way if you smoked on the porch. Daniel always bought cigars for clients.

“Mom bought this for me to wear to prom, but I didn’t go. I chickened out. I never got a chance to wear it. Do I look okay?”

The dress was too big—the sleeves drooped off her shoulders and the bodice gaped at the bust and waist. How was she so much smaller at forty than at fifteen? She wore too much red lipstick—there were smudges below her mouth. The white powder on her face made her look like a ghost, reminding him of Olivia in her coffin. He wanted to tell Hayley to change. He didn’t like being embarrassed. But he forced himself to smile. “You look nice,” he said. Then he opened the door, and she followed him outside.

—

Daniel had forgotten it was Friday, and they had to wait a long time for a parking spot. Hayley hummed beside him, tapping her fingertips on her knees. He clutched the steering wheel, wondering if he’d made a mistake by inviting his daughter to dinner. But Olivia’s words reverberated in his head. “Promise me you’ll talk to Hayley. She’s in a bad way.”

—

They had to put their name on a long list and there was nowhere to sit to wait. They stood by the porch, where the air smelled like smoke and beer. Mosquitoes hummed in Daniel’s ears and he smacked the bugs away. Hayley kept curling a lock of hair around her finger, letting it go, and doing it again, a habit from her teen years. Daniel could feel the stares of the other patrons when they noticed Hayley’s dress. He kept a smile on his face, praying no one would comment. It wasn’t likely he would see anyone he worked with at the restaurant. They frequented the places in town or the club, where hush puppies weren’t an option.

Finally, their name was called, and they struggled through the knot of people to the hostess stand.

A girl in jean shorts smacking gum led them to a table in the middle of the restaurant, beside a table of guys wearing baseball caps. Daniel felt their eyes on them, and he glared at the biggest one, a burly guy in a Gators sweatshirt. Hayley said she needed to use the bathroom as soon as the hostess set their menus on the table.

It was so loud that conversation wouldn’t be possible. Daniel was grateful for this because his daughter was acting so strangely and he didn’t know how to find out why. Seeing Hayley twirl her hair brought back bad memories of sitting across from her at the dinner table. A typical night: Olivia chattered about the candlesticks she’d just bought from QVC while their daughter twirled her hair and didn’t say a word.

Then there were all the absences in high school. Olivia made excuses. “She’s not like the other girls. She’s sensitive. I can’t make her go when she’s sad.” But why was Hayley sad? He’d never understood. She had everything: diamond stud earrings that matched Olivia’s, an Audi TT when she turned sixteen. But more than material things. Daniel had given his daughter promise. Possibilities. The perfect start to a perfect life. Much more than he ever had, growing up in rural Alabama with a single mother who could barely scrape together enough money to put tuna fish on the table.

Hayley could’ve gone to any college in the country if she’d just kept her grades up. But she hadn’t. The only college that accepted her was a tiny one in North Carolina, which she returned from on holidays eager to read them poems she’d written. He remembered one in particular—she said her heart had been attacked by tigers and there were teeth marks in the aorta. The poem was titled: “Mother.”

Olivia had started crying when Hayley finished. Daniel’s first impulse was to comfort his wife, but she’d jumped to her feet, clapping her hands. She called Hayley a genius, framed the poem and hung it on the bathroom wall. It looked at him while he brushed his teeth. “She hunts me nightly. She never wants to let me go.” Hayley’s poem seemed to be a negative reflection on his wife. So why did Olivia like it so much? Daniel couldn’t fault his daughter for her feelings—after all he would’ve liked to write mean poems about his wife, too. Daniel didn’t understand poems. And he knew then he would never understand his wife and daughter. He’d always be on the outside, walking by the den where they huddled on the sofa, sharing a bowl of caramel popcorn.

Hayley returned to the table, her lips redder, her face paler. She sat down and the waitress appeared, barely glancing at them, scrawling their orders down on a pad. Fried shrimp for both of them. Hayley wanted a glass of white wine. He wanted a scotch and soda.

The drinks didn’t take long and thankfully, the food didn’t, either. While they ate, Hayley twirled her hair and stared past him or studied her phone. He played with the dial on his Rolex, watching the time creep past.

When the waitress passed by to ask if they wanted key lime pie, Daniel handed her his American Express.

He met his daughter’s eyes across the table, and she smiled. She seemed to be on the verge of saying something, but then her smile disappeared and she stared at the half-eaten coleslaw on her plate.

“Still making cappuccinos?” he asked, searching for something to say. And then to his horror, Hayley began to cry. So, she had lost her job again. One second she was smiling and now her shoulders shook, quiet sobs wracking her body. Daniel remembered Olivia’s words again: “She’s in a bad way.” What should he do? He thought about client dinners, but no client had ever cried before.

Eyes on them. The men at the table nearby. Theirs was not the kind of community where you had a breakdown over coleslaw. “The land of the raised pinky” is what he’d told his wife once and she said: “We’re lucky to live somewhere so beautiful. Don’t complain.” Daniel had to get them out of the restaurant. The waitress returned—thank God—he signed the bill and grabbed his daughter’s arm.

He was grateful to be outside again. It meant the night was almost over. He breathed in the chilly air and thought of his roses. The cold would do them good. He hoped the person who bought his house would care for them the way he had. He should probably pass along his tricks: eggshells and tea bags in the soil, olive oil rubbed onto the leaves.

They were almost to the car when Hayley’s name was called. Oh no. Who could it be? Had someone seen her crying? The caller was a pregnant blonde woman in a floral dress.

“I thought that was you,” she said to Hayley, whose eyes were wet and frightened. “This your father?”

She stuck out her hand, and Daniel shook it and introduced himself.

“Elizabeth,” the woman said. “Hayley and I went to high school together.”

She told them she practiced obstetrics at Baptist Medical, that she was on her way to the hospital because one of her mothers was going into delivery early, much to her husband’s dismay since they’d been celebrating his birthday.

“My drunk husband can’t drive me to the hospital, and with my belly I can’t fit behind the steering wheel—could you give me a ride to the hospital? It’s less than a mile away,” Elizabeth asked.

This was the last thing Daniel wanted to do. He needed to get Hayley home, rescue them from the awkwardness of the night. Who was this Elizabeth? Couldn’t she call a cab? He could feel his daughter’s eyes on him.

“Okay,” he said.

Hayley went back to twirling her hair. She walked behind them. Elizabeth got into the front seat. When he pulled out of the lot, Elizabeth looked over her shoulder and smiled at Hayley.

“What are you doing these days?”

Daniel glanced in the rearview mirror. Was Hayley crying again? He didn’t want her to answer. She was a middle-aged woman who’d been hospitalized for bipolar disorder following a suicide attempt. This Elizabeth—she was the kind of woman Daniel had imagined Hayley would turn out to be. A doctor, pregnant, happily married. Assertive enough to ask an old schoolmate for a ride.

“I’m so proud of my daughter,” Daniel said, the lie falling out of his mouth so fast he couldn’t keep up. “She’s a brilliant writer. A poet. She lives in Los Angeles now, and I don’t see her enough.”

How had he come up with this so quickly? Five minutes ago, he’d been unable to think of a single word to say to his daughter, and now he was expertly lying to a total stranger. Maybe it was all those years convincing juries. He didn’t know but he felt proud of himself for jumping to Hayley’s rescue. He’d saved them both from embarrassment.

Elizabeth snapped her fingers. “I remember,” she said slowly. “We were essay partners in American Literature. Your papers were always the best.”

Hayley stopped chewing her cheek. “Really?” she asked.

“Oh yeah,” Elizabeth said. “I’m not surprised you’re a writer now.”

“I wrote a book,” Hayley said proudly. She opened up her purse and pulled out a worn copy. She passed it to Elizabeth. Daniel had never read his daughter’s book. He’d been too freaked out by the title, which had been the name of a song he wrote in college for a class. The only time he’d ever done something creative. He had no idea how Hayley got her hands on the song—he’d assumed it had ended up in the trash, like all of his college papers.

“Broken Nightingale,” Elizabeth said, staring down at the cover. “That sounds good.”

“Thank you,” Hayley said.

Elizabeth handed the book back and gave Hayley her business card. She suggested they have lunch the next time Hayley was in town.

“This is my last trip here,” she said. “My father’s moving to Jacksonville.”

“Shame,” Elizabeth said and then: “You look great.”

Hayley’s eyes grew wide. Daniel turned into the hospital parking lot and drove to the entrance. Elizabeth thanked him for the ride, and they all said goodbye. Daniel was certain now that the sadness inside of him was written all over his face, and he clenched his jaw as hard as he could. When Elizabeth got out, Hayley didn’t take her place in the front seat. They were quiet on the ride home.

When he pulled into the driveway, Hayley said, “I’ll be out of your hair in the morning. I booked an early flight.”

She was leaving? But she said she had nothing to go back to? She’d bawled at dinner. For the first time Daniel missed Olivia. She’d do something, even if it was the wrong thing.

They went into the house. Hayley went to her room. Daniel stood in the kitchen, staring out at the dark backyard.

—

Daniel got out of bed just as the light in his room turned pink. He went to Hayley’s room. He wanted to look at his daughter one more time before she left. She slept on her side, the covers down by her ankles. She’d slept like that as a little girl. Now her hair was short, but she looked just as peaceful. He wished she could know that peace, that her brain wasn’t so mixed up, that she didn’t get sad enough to want to die. Maybe her brain would’ve been different if he’d been a different father. If Olivia hadn’t been her best friend.

Hayley stirred. She opened her eyes.

“Daddy,” she said hoarsely.

Daniel’s heart pounded. He might never see his daughter again. She’d have no reason to come home now that there was no home to return to. She wouldn’t travel all the way back to Florida just to see him. The yard was beautiful in the morning. Maybe she’d like to see it one last time.

“Come outside,” he said.

She rubbed her eyes and sat up. She followed him, in bare feet, in her old T shirt and boxers, to the backyard. Now the sun was higher. Dew sparkled on the grass, made the tips of the blades look like diamonds.

Hayley turned to him, tears in her eyes. Should he hug her? Maybe she didn’t want to be touched. He tried to choose a word, any word, but his mind had gone blank like it always did with his daughter.

“I’ll have a balcony at the condo,” he said. His voice sounded strange to him, far away. “Would you help me pick out plants for it? A cactus maybe?” He wasn’t sure what he was saying, only that he was heading somewhere when a few moments ago he’d been at a dead end. How could he speak to packed courtrooms but not his daughter?

Her brow furrowed and she seemed on the verge of saying something. But then she stopped. This was a terrible idea. He should let her go. All of his earlier efforts had been futile. Why did he think he could help her now?