The Florida Review is pleased to announce a new award focused on poetry with environmental themes and concerns. An anonymous donor is providing funding for the new Humboldt Poetry Prize in honor of Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859). A winner and two runners-up will be chosen each year from work published in the previous year in The Florida Review and Aquifer: The Florida Review Online. Each winner will receive an award of $500, and each runner-up $250.

2019-2020 Recipients

We are also pleased to announce our first-ever winner and runners-up for the Humboldt Poetry Prize:

- Bethany Schultz Hurst for “Notes on Pet Monkeys and How to Handle Them,” winner (TFR 43.2, Fall 2019)

- Doug Ramspeck for “Long Marriage (Parable of the Skull),” runner-up (TFR 43.2, Fall 2019)

- Jacqui Zeng for “Natural Order,” runner-up (Aquifer 25 February 2019)

This year’s judge was David Keplinger, author of six collections of poetry; winner of Rilke, T. S. Eliot, Cavafy prizes; the Colorado Book and Emily Dickinson awards; recipient of two NEA fellowships; and Professor of English at American University. About the winning poem, he had the following to say:

Bethany Schultz Hurst’s exquisite response to an 1888 colonialist manual on the “management” of captured animals uses the erasure form in concert with the rigor and formal limitations of the sonnet to study the mistreatment, ailments, and murder (“with an iron bar a sharp and heavy blow”) of the monkey transplanted from its natural environment into a human menagerie, and whose existence there plays out like some profane translation of a sacred text. In the final sonnet in this sequence, the skinning and posturing of the dead conclude with the instruction to “Keep him in full light.” What a brilliant use of artifice to reverse that spell; to bring atrocity to light; to classify the crimes of colonialism; to speak out against what Empire has enacted in the name of power and spectacle.

The Humboldt Poetry Prize

Each year, one winner and two runners-up will be chosen from work published in The Florida Review and Aquifer: The Florida Review Online during the previous calendar year. Candidates will be identified from all categories of works published—those that stem from general and contest submissions, as well as from solicited work that we have published.

The Florida Review was chosen by the donor to administer the Humboldt Poetry Prize due to our long-standing commitment to and appreciation of poetry along environmental themes. We hope that the existence of the prize will encourage even more and stronger submissions of such work, but we chose not to create a separate submissions category for it because we hope not to segregate such submissions. Writers should feel free to identify in their cover letters whether they believe their work includes an environmental component. But all work must first be considered alongside our other submissions and published in the journal before it will be considered for the Humboldt Poetry Prize. Poems will be selected based on the criteria listed above, and an external judge will be selected by the editors to make final decisions.

Criteria set for the prize include:

- Probing the capabilities and needs of wild animals and challenging their exploitation;

- Exploring wild animal/human relationships;

- Experimenting with and imagining the subjective life of wild animals;

- Interrogating the poetic use of animals simply as metaphors;

- Investigating natural processes, biospheres, and their complexity; and/or

- Pondering awe in the face of nature and/or how to inspire such awe.

Each winner will receive an award of $500; each runner-up an award of $250. In addition, with each poet’s permission (or that of any subsequent book publisher), the poem will be reprinted. Works originally published in Aquifer will be reprinted in the print Florida Review, and vice versa.

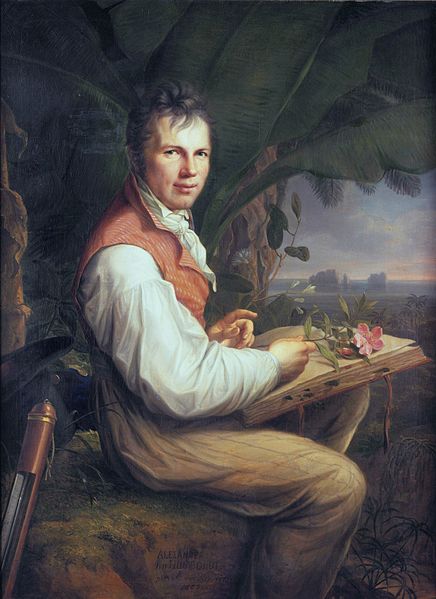

Alexander von Humboldt

The new prize commemorates the legacy of the visionary German naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859). Humboldt’s fascination with natural processes started in childhood, when he earned the nickname “the little apothecary” and continued throughout a fifty-year career as a famous public figure, in which he investigated the fields of botany, minerology, geology, isothermal mapping, meteorology, and geodetic and geomagnetic measurement. During the Napoleonic Wars, he set off to explore Central and South America and, with a French botanist, covered 6,000 miles by foot, horseback, and canoe, studying astronomy, topography, flora and fauna, and the Earth’s geomagnetic field and barometric pressure, as well as mapping 1,700 miles of the Orinoco River. They measured the river phenomenon now known as the Humboldt (or Peru) Current.

Humboldt also succeeded in marrying science and aesthetics, promoting the belief that every element of nature is dynamic and interconnected, and that these forces should be apprehended with both head and heart. In thirty volumes published during his lifetime—and filled with detailed illustrations and lyrical descriptions—Humboldt taught that nature, properly understood, stimulates the imagination as well as the intellect and is a source of beauty and consolation. His close friend Goethe noted that “with an aesthetic breeze” Humboldt lit science in a “bright flame.”

As the first scientist to identify climate zones and view the Earth’s ecology as interconnected and ever-changing, Humboldt anticipated the deleterious impact on wildlife and the biosphere, and he frequently decried the careless environmental destruction of Europe in the colonies. Even as his fame and wealth diminished later in life, Humboldt assisted many young scientists in embarking on their careers. References to his ideas appear hundreds of times in Charles Darwin’s writings, and he profoundly influenced John Muir and generations of conservationists and nature writers.

We at The Florida Review hope to continue to encourage those writers concerned with the human relationship with our planet and with the beauty and power inherent in the Earth in the tradition of the writing of Alexander von Humboldt.