Tag: Aquifer: The Florida Review Online

Forthward: Guy Psycho and the Contemporary Epic

Guy Psycho and the Ziggurat of Shame by John King

Beating Windward Press, 2019

Paperback, 206 pages, $17

Epic heroes are traditionally paragons of the societies that invent them, extolling the virtues that those societies find most desirable. Guy Psycho, aging rock star and titular hero of John King’s debut novel, Guy Psycho and the Ziggurat of Shame, is no exception in that regard. He’s a hero for the postmodern era, and so he’s somewhat different from his classical counterparts: He’s tall and thin, in black lipstick and eye makeup. He wears Wayfarers and wingtips (size 14). He has a surgically implanted voicebox that occasionally goes on the fritz, causing him to blat certain syllables with a tinny, synthesized version of his otherwise golden pipes. And, far from being the sole agent of fulfilling his quest, he gets through most of his adventure due to the unfailing support of his band mates: from the musicians, to the discretely differentiated backup-dancing Postmodernaires, to the band’s new manager and accountant. Their adventure, like their professional lives, is something that they all do together.

The book doesn’t only evoke epic literature stylistically and thematically, but literally. The story itself is a wild romp through the tablets described in The Epic of Gilgamesh, as Guy and the crew are plunged into a dreamlike prehistory in search of the lost thirteenth tablet, which they have to find before an angry Ishtar and the other Sumerian gods destroy the world. King lovingly deconstructs the larger-than-life deeds of the original Gilgamesh and gives us a different, almost surreal reinterpretation—or, really, a reiteration—of them.

Along the way, he relies on several distinct elements of each character that quickly become their own sort of nods to traditional heroic epithets: Guy Psycho of the size-14 wingtips and Gaultier gauze, Lulu of the auburn hair and motorcycle boots, Trudy of the black ringlets and silver-ruffled party dress. This also helps further differentiate the various characters (there are eighteen) in a relatively short amount of time, as all of them are far more complex and interesting than they initially appear—the musicians are more than the instruments they play, and every single one of the Postmodernaires has something more than mere dance steps that informs their voices and characterization.

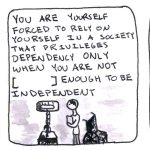

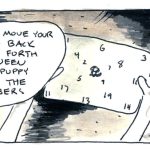

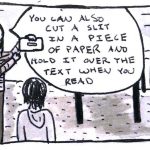

Despite the book’s clear love for the classics, the rest of its presentation is a playful, joyful rejection of convention, as King enjoins the text itself to participate in the narrative. Pages go black as characters are plunged into darkness, punctuated on the next page by cones of onomatopoeic flashlight. Lines of narration from characters lost in a maze spiral around the page in neat right angles, helping drive home the sense of uncanny disorientation. Far from seeming distracting or gimmicky, this quintessentially postmodern acknowledgement of the text as an ontologically distinct artifact reminds the reader to enjoy not just the book, but the experience of reading the book. King includes small moments of explicit and implicit intertextuality, as well, that drive home the point that the book doesn’t exist in a vacuum; the astute reader is rewarded for Googling the serial number on the otherwise nondescript crate in Mr. Youngerman’s curio collection, for example, or for noting the title of the book one of the guests at the Bull of Heaven’s party is reading (which, with any luck, is the tacit promise of a sequel).

The language, too, at the sentence level, is a melodic free-form jazz of excellent description, fluid and rich in metaphor, that whisks the reader effortlessly along through the book’s two-hundred-or-so pages. For example, during a reminiscence, Lulu, a Postmodernaire with a background in archaeology who helps guide the crew through ancient Mesopotamia, reflects on when she hit rock bottom:

Lulu remembered, in a single flash, a time when her face was mashing her nose down against a tabletop, her sweaty, auburn hair crawling with sticky airs, in some murmuring necropolis of a bar in the underside of Tangiers. . . [H]ere she was, across the globe, a cipher in a ledger that no one would ever read, an empty egg cracking in the back of the fridge.

The visceral detail, the vibrant verbs, the fresh and interesting figurative language—all are typical of King’s prose throughout the novel.

In addition to the quality of the language, the passage above also illustrates one of the things that makes the novel work so well: while it never loses its spirit of fun and adventure, King isn’t afraid to treat his characters seriously, to let the reader in on their doubts and vulnerabilities. The nagging problem with many of the ancient epic heroes is that they were portrayed with precious few real faults, few true weaknesses, save a near-ubiquitous hubris. This worked for the societies who birthed them, who seemed to desire these larger-than-life supermen. Guy Psycho and his coterie, however, are products of the contemporary (or postmodern) age, so a big part of their heroic nature comes from their courage in the face of their own faults and personal tragedies. The result is a story that not only has a harmonic resonance with the ancient adventure tales—in a way, the forebears of the craft of fiction itself—but a story that still has a melody all its own, that doesn’t hesitate to march “Forthward!” in an attempt to excavate a new niche in the bedrock of myth—and turn it into a rock-and-roll stage.

Two Poems

To My Caring and Worried Mother

There are sliced carrots in the shape of a cowbell,

because I understand

that great food should sing to you.

There’s a movie we’ve never seen before

and a Japanese instruction manual.

There’s a novel about Alzheimer’s

and some magic memory pills for your mother.

There’s an automatic food dispenser

so you don’t have to bend down to feed the dogs anymore.

There’s a travel bag with a Bible

and a plane ticket to Paris.

There’s a color-coded flow chart

describing the best way to carry a conversation with Grandma.

In the bottom right hand corner, in fine print, it explains

you may have to adopt new tactics on the fly.

I caught Grandma watching

The Hulk in Spanish today.

I just flipped to the English version.

To my caring and worried mother:

raising your voice won’t help,

there is no cure.

All the Post-It notes

on all the cabinets

should say: open with caution,

eat with intensity,

remember,

we love you

and we’ll help you

find the watch

you stuffed in the cookie jar.

Elegy

The horse

nuzzles the back of my hand

as if the damp home of its nose

could stand not one more dark

second of this unfettered freeze.

What of it,

she asks after we’ve had our hot

meat and stale versions of drug,

sitting in lotus pose

facing my grandfather’s headstone

where every engraved sentence

curved tinsel of truth

into the steaming mouth of myth.

This barrel-bellied man

made a small southern town

seem like a place God had visited

and forgot to bless.

He was that damn bold,

that unforgettable.

Before & After the Pinnacle of Happiness

The Truce: The Diary of Martín Santomé by Mario Benedetti

Translated by Harry Morales

Paperback, Penguin UK, 2015

“In only six months and twenty-eight days I’ll be in a position to retire.” So begins Mario Benedetti’s The Truce—a novel that takes the form of the brief and intimate diary of the forty-nine-year-old Martín Santomé, a Uruguayan widower living in Montevideo in the 1960s. Martín’s attention to life’s mundane details, like the shapes of strangers’ legs and his coworkers’ nervous sneezes, combined with his frequent accounts of exhaustion, are what make him feel real and familiar right away. Although his world is small and provincial, his reflections are universal.

The novel was originally published in Spanish (Editorial Nueva Imagen, Montevideo, Uruguay ,1960) and was published in English by Penguin UK Modern Classics in Harry Morales’s English translation in 2015. Readers should be grateful to Morales for not only capturing the contradictory nuances of Benedetti’s resigned-yet-open voice so perfectly in English—but also for inviting a wider audience to enjoy this timeless story of love and sorrow. The translation in today’s context gives the novel a fresh, new meaning. The novel is about learning to appreciate the present, but the way in which it approaches the present is charmingly old-fashioned.

Early on in the novel the protagonist’s daughter, Blanca, laments to her father, “Sometimes I feel sad, over nothing more than not knowing what I’m missing.” The girl’s sentiment is one that hardly exists today. On the contrary, modern readers tend to be acutely aware of what we are missing; we are inundated with online images and texts that remind us of what-could-be on a daily basis. It’s amusing to think that the very reality we have now is what Blanca might have been yearning for. Yet it’s precisely this feeling of Blanca’s desire—a desire her father also shares—that serves as the emotional premise for the entire novel.

The novel embodies the thrill one feels when finding something he never even knew could happen. It’s about the retrospective discovery of a hole—a discovery made only after that hole has been unexpectedly filled. In the case of our protagonist, this hole is romance. Romantic love is the last thing Martín Santomé expects or even wants to find. He is tired. He seeks only leisure and some rest, yet at the same time is depressed by the prospect of a blank agenda. The love affair he begins with his twenty-three-year-old assistant, Laura Avellaneda, just before he enters his retirement, is hardly original. But it’s the way in which this experience moves and reinvigorates him, that is so potent and inexplicably memorable.

Martín’s celebration of his own surprising happiness is made all the more intense by his keen acknowledgement and understanding of the fragility of life and its transcendence. In a small moment midway through the novel he narrates:

She had got out of bed, just like that, wrapped in a blanket, and was standing near the window watching the rain. I approached, also looking at the rain, and we didn’t say anything for a while. All of a sudden, I realized that that moment, that slice of everyday life, was the highest degree of well-being, it was Happiness. Never before had I been so completely happy than at that moment, but still I had the cutting sensation that I would never feel that way again, at least at that level, with that intensity. The pinnacle of happiness is like that, surely it’s like that.

Martín Santomé’s unexpected bliss is poignantly balanced with an underlying fear of loss: “Are we burning?” he asks his lover. The novel beautifully explores the frightening contradictions that are inherent in love, and it’s easy to see why the book still stands as such a revered classic in Latin America, and why it deserves to be read everywhere else. Harry Morales’s translation of La Tregua is a novel you will read without stopping and will never forget. It will be a physical experience that marks you, twists you, and pulls something out of you. It will make you weep and narrow your eyes at details you’d never before noticed: the wood of a table, a dog outside a window. It will make you think about your own emotional life like a chart on paper: where do the peaks and the valleys lie? And, most importantly, what happens in between them?

Love Like Orange

My father’s love was orange. It could be warm and milky like summer Creamsicles, boisterous and magnetic as a dancing flame, or deep and foreboding as the morning sunrises sailors avoid. Every Saturday morning, he clocked in, arriving at my grandmother’s house at nine in the morning. My brother, Justin, and I waited at the front screen door, fidgeting and rocking in our criss-cross-applesauce positions, my mother standing in another room biting her nails.

We only needed our ears to alert us of his arrival: the slow whir of a car driving past the house followed by the crunch of gravel as it made a U-turn. The barely detectable squeak of brakes as a car came to a stop. The slam of a heavy door closing, the clap of footsteps, and, finally, the chirp of the car announcing the locking of its doors.

Sometimes he arrived bearing gifts of the stuffed bear variety or a chocolate orange wrapped in bright tinfoil that, to us, was as valuable as real gold. And other times he arrived in ghoulish masks to terrify Justin.

“For Christ’s sake, stop being a baby,” he barked in irritation, removing the Alf mask as my brother sobbed and hiccupped from fright.

“He’s only three; of course he’s scared,” my mother cried, stroking Justin’s back.

“You’re always babying him.”

These standoffs between my parents could last for as few as thirty seconds and as long as weeks. Tears could quickly turn to laughter as we climbed the apricot tree, bright green with orange fuzzy polka dots hanging from limbs and littering the grass.

In the backyard, Justin giggled while swaying forward and back in a swing fashioned out of a splintered four-by-two plank and manila rope as course as sandpaper.

“Higher,” he laughed. Our father obliged.

He was ours until sunset when he clocked out just as swiftly as he’d arrived. While walking to his car, we sent him off with a parade of waves, parroting “Bye! Bye! Bye! Bye!” back and forth as if he were leaving for war and we didn’t know when he’d return. The bright orange sky bounced off his car as it pulled out onto the road.

We waved with our apricot-stained hands until his car disappeared down the street. These days escaped us in a blur of tickles and laughs and tears and shouts and sweet coos of love. We would forget almost everything except the tang of orange that sat bitterly on our tongues.

—

My father’s love was indigo, as deep and distant as the continental slope we feared would swallow us whole. Sitting on his shoulders, I levitated five feet and nine inches above the ground, scanning the ocean for whales we’d never see this far south.

“Be careful,” my mother warned, which only instigated him to run.

I bounced on his bony shoulders, and then slipped forward and onto the sand. My mother and Justin screamed, and my father scowled, an electrical current of smoky, rich blue pulsating from his veins. Above me, furrowed brows and wide eyes collided, but all I saw were their indigo shadows wrestling on the sand. My mother surrendered, but my father’s palms were stained electric. He stormed ahead of us at a gait our legs couldn’t match.

We called for him: “Wait! Wait! Wait!”

He was too far ahead and could only hear the waves and seagulls, or so he said later. We lost him among the sea of beach umbrellas and Styrofoam coolers and barbeque smoke and waxed surfboards.

On the pier, we had a better view, and we each claimed a direction to survey. We spun around hoping to pinpoint the man with dark hair, dark eyes, and tanned skin. My mother always said he looked like a Greek fisherman, so we looked to the ocean beyond the end of the pier for the dark shadow of a man who’d had enough of life on land and all that comes with it. We felt for his currents of indigo that connected him to us like an invisible leash that tied families together.

“Frank!” my mother shouted.

“Papa, papa, papa,” Justin and I repeated.

And then, as always, he materialized behind us.

“I’m right here; you can stop making a goddamn scene with your hysterics.”

If there’s one thing my father hated more than life among mortals, it was attention from them. We followed him back to the car, our legs marching in double-time to keep up with his long strides. He fought in Vietnam, but the leave-no-man-behind warrior ethos did not apply here. Our feet sunk as the sand grabbed at our ankles, and we hoped we wouldn’t be left behind.

—

My father’s love was cherry—tart and sweet in the same bite. It was layered with unexpected gestures we loved and hated and from which we ran away only to return and beg for more.

On Christmas, we saw life through cherry-stained glasses. Our living room transformed into New York City, with the dozens of crimson-wrapped gifts as its skyscrapers. It took hours to unwrap everything, and when it was over, we hunted for more and painted our father red with tinsel and kisses.

With flushed cheeks and dilated pupils, we ran in circles, incapable of exhausting ourselves. We scrambled up couches like Mount Everest and excavated cardboard boxes for buried treasures, stopping only for a bite of chocolate from our stockings.

“That’s enough,” my father warned us. He was jubilant until he wasn’t.

I always received half a dozen warnings, but Justin was only given two, which was never enough for him.

“That’s two,” my father barked, standing from his seat.

Justin screamed and ran for shelter. When they returned from the back bedroom minutes later, one of Justin’s wrists matched the scarlet of my father’s right palm; it was what inadvertently linked them, like father-and-son tattoos that faded and then returned weeks later.

Justin’s eyes were carmine from crying, and I wondered if everything he saw was the color of Christmas. He rubbed his wrist while I connected the constellation of kisses left behind from my mother’s ruby lipstick that stained his cheek and forehead.

—

My father’s love was white—silent and opaque, hovering in a corner just above our reach. When it wasn’t bright and all-encompassing, it was the very absence of light, siphoning its warm comfort that engulfed us moments ago.

While Justin and I lived with our mother and grandmother in a rugged and familiar landscape of chipped paint, peeling wallpaper, and nail polish–stained quilts, my father lived in a glass castle, off limits except for today.

His house was a museum with carefully placed breakables that toed the edges of shelves. There were white ceramic vases with silk flowers, bronze elephants that, at the right time of day, sparkled under the skylight. There were hand-painted boxes from Russia, miniature Chinese floral vases, a globe made from rare minerals, and a cream-colored bust of Poseidon. They were untouchables we stared at with open jaws and wide eyes while on tip-toes, stroking the invisible barrier that hovered around each one.

We ran in the white glow of this castle until my father’s forty-five-year-old hands caught Justin’s three-year-old neck and forced him to the ground.

“How many times have I told you to be careful? You can’t just run around like a goddamn monkey. This isn’t a zoo!”

His booming voice had the incredible ability to vibrate through our bodies and cause our bones to shake in fear. Justin’s face turned white and, with wide eyes, looked pleadingly at my mother.

Disgust washed over my father’s face.

“Go. Run to your mother.”

“Go to him. You need to go with him,” my mother whispered to me.

I shook my head.

“Go, or he’ll just get angrier,” she pleaded.

I was the only one who could placate my father, a badge of honor I would have done anything to shed. After my father died, these memories felt traitorous. I would spend years repainting my past, searching for new hues, but I always returned to the same four, ending with this blinding white that would never fade.

Refusing to look back at my mother or brother, I stomped toward my father who snarled like a mountain lion in his cave of an office. My brother and mother retreated to a corner, licking their wounds. I cajoled my father with pleas for mercy and, eventually, guided him back to the living room where we lapped up his renewed love like milk.

Two Poems: 2001 & Barbie

2001

There was no space odyssey.

Instead, more than towers fell

in the city where I live.

People were still counting

paper scraps in Florida

for the sake of a flawed process.

People were still dying

in Gujarat’s earthquaked cracks

in Ghana’s stampeded stadiums

and in the summer of the media

calling shark attacks on Santa Rosa

a national security threat.

The Taliban’s advent, McVeigh’s execution

for destroying what seemed an entire city.

I had just turned seven.

For my birthday, my mother

bought me a Beatles CD.

Later that year, George Harrison died—

my favorite one, the one

who sang about how all things must

come to an end. But

how were endings possible

in a new millennium? New

Wikipedia, where we learned

how to summarize. New Nokia,

new Madonna, even language felt

refreshed: A.I., iTunes, OS X, Xbox.

It was the first time I broke my arm

in two separate places. I visited the zoo

and watched the animals roar at each other,

and at themselves. My mother dispelled

Santa Claus, perhaps a year too soon

for my imagination to take. I cried

until I received extra presents

for keeping the secret from my sister.

I saw myself in the Backstreet Boys,

in the highest rated Super Bowl in history,

as Harry Potter, whether philosopher

or sorcerer. Everything still felt possible

to a seven-year-old, who had just

heard about the first tourist in space

and thought it was an odyssey.

Barbie

I comb my hair with a small hairbrush.

I no longer walk in nature. And when

I sit on the front porch, sipping

whatever’s left from the mason jar

filled with all that last night, I flick

the maggots from my skin.

The parked car outside the house

sits with its tarped over cover since before

I remember. I remember

playing dolls with my sister

while my father wedged a football

into my hands, and said

you must throw as far as you can.

Open wide, my arms onto the wheel

where I learned how a man

drives five miles above the limit.

It was cold that first Kentucky,

where I first kissed masculine lips,

wet as leather, chapped the way

we hid from what we learned

in locker rooms. We grazed the sides

of our heads against the Cypress bark.

While we leaned against its trunk, I saw

pigs in the distance, wrestling

in the nightmud. They cannot know

how soon they will be separated, then skinned.

I Wake at Four & Drive to the Mountains

To leave the inner critic on the empty street beneath my windows.

To outride the arrows, or slings at least, of civic life.

To put the forces separating me from my daughter—the moderator

in elastic-waisted slacks, the decree signed

by the liver-spotted judge—in the rear-view.

To look ahead and see the world’s impersonal love song again

lifted from night.

To know the song is about the attention we give the wild,

unfixable everything we love yet is always already

indifferent to us.

And yet to see the sun rise, like a couched friend, from blankets of fog

in the lowland orchards.

To see the fields of our anxieties cut and gathered in silos.

To hear the wind wrap us, undeserving, in the sun’s resolve

to sustain us another day.

To stuff a campsite into my backpack and somehow walk ten miles.

To feel the weight of our basic needs shouldered across streams,

over hills, up crevices.

To remember having walked the home-forsaken trail before.

To realize I’d compressed memory of all this pain—all but the sacrament

of red, gold and orange leaves

above river bluffs.

Only here do I realize I must have forgotten just how many uphills,

just how fucking much elevation hurts.

Here I think such thoughts as our sapiens ancestors ground as many miles

over mountains each day.

I wake and drive and walk to think: Perhaps the downhill mortar and pestle

of our patellae almost crushes recall

of profane elevation.

And to meet the inner critic, somehow already at the top, and

to accept his message:

You wake at four and drive to the mountains

to accept the body’s pain as the cost of all the beauty there is to see.

To My Fellow Submitters

A found poem from sample rejections saved in “My Submissions,”

completed in response to a writing prompt given at

the Sandhill Writers Retreat, May 2019

Dear

Dear

Dear

Our poets’ community is lucky to have you

Good fortune in all your future writing

Declined

Cannot offer

We enjoyed having the chance to read

Many excellent entries this year

The team wishes you

We wish each of you the best in finding publishers

All the best

Unfortunately

The sweat and the perseverance it takes to put together a submission and send it out, naked

Declined by

Not Selected

A strong and competitive batch

A complimentary copy of this year’s

We regret

We are grateful for your ideas

We encourage you to submit again in the future

We are unable to provide individual feedback

Thanks

Best

Appreciate the dedication to craft

Thank you for choosing us

Hope that you and your work succeed in finding a home

You’re now one step closer to getting that acceptance you’ve been looking for

Sincerely

In peace and poetry

The Ball Spun

I arrived at the playground with Armin. It was a late afternoon in June; the rays of sunshine broke through the thick white clouds in places, illuminating patches of the tramped grass. Armin’s parents had sent him another package, a brand-new soccer ball in it. It was yellow with blue spots. He held it close to his chest as we sauntered down the street to the playground.

Armin and I hung out regularly. He lived in my neighborhood with his grandma. Armin’s parents worked in Austria as guest workers. Most of his life he spent with his grandma, seeing his parents once a year. Armin had toys I’d never seen before: remote-operated cars built of high-quality steel, model planes, and handheld video games. He brought to school all sorts of foreign candy, neatly wrapped, colorful, with pictures of cartoon characters.

Armin talked a lot, while I was a quiet type. He talked so much on our way to school that we often ended up being late. When I stopped by his place before school, I’d find him in the bathroom in front of the mirror, looking at himself and combing his blond curls. “What do you think, Edi?” he’d say. “Looking good, man. That schmuck, Sinan, is a goner. Selma is my girl. Hey, let me show you a new thing I got.” He was never ready on time, and the school was three kilometers away—a long walk.

The playground was deserted. We started kicking the ball from one rusted goal post to another. A few minutes later, we noticed a group of boys walking towards us. They were in their late teens. As soon as we saw them we knew we were in trouble. After all, two eleven-year-olds stood no chance against a gang of high-schoolers. Their ring leaders were two brothers. The older brother, Kasim, was as dark as the asphalt on the road he’d just crossed. He was skinny and long—all limbs. His round head bobbed on top of his body like a ball with two black eyes perched above a bulbous nose. Kasim’s brother, Vedad, was a year younger. He had long, brown hair he’d always tie into a ponytail. Vedad was notorious for his vicious smile that revealed two long canines. He was short and sturdy, his legs sinewy and fast. He was the best soccer player in town.

Kasim intercepted our pass and took the ball. Vedad shouted, “Come on, man! Be nice and share.” Kasim kicked the ball hard to the other three boys trudging behind him.

“Give the ball back, assholes!” Armin blurted out, and before finishing the sentence he looked at me, surprised by his own words.

“Whoa, man! The kid’s got a foul mouth.” Kasim sniggered. “Isn’t that Aunt Zinka’s grandson?”

“Time to teach him a lesson,” Vedad said. He picked up the ball like a pro, bouncing it on his knees, his ponytail prancing up and down. “Tell me, little punk!” he said. “Whose ball is this? It’s damn good. Real leather. Made in Germany.”

“It’s mine,” Armin said.

“Of course, little chicken shit.” Vedad said. “Did your mama send it from Germany?”

“From Austria,” Armin shot back.

“Would you, please, give us the ball back?” I interjected.

“This one here is a nice boy.” Vedad nodded towards me and balanced the ball between his foot and his shin.

“Listen, nice boy,” he said. “I have an idea. You get the ball and we let you play if you two show us your kung fu skills.”

“No way,” Armin cried. “You guys will mow the lawn with us.”

“Who said we’d do anything?” Kasim said. “We don’t fight little pussycats. We want you to fight each other.”

“Why would we do that?” I said.

“Because that’s the only way you get the ball back. And if you beat this mama’s boy, the ball is yours. Isn’t that so, mama’s boy?”

Armin looked at me, then at Vedad and Kasim. “The ball is mine,” he said.

I held my gaze on Kasim and nodded hesitantly. As long as I could remember, the only soccer ball I ever had was a bubamara, which meant ladybug. The bubamaras were often the only choice for the working-class kids in Yugoslavia. They were made of cheap rubber and lasted only for a few weeks. After a couple of good games, bubamaras turned into sad-looking, egg-shaped spheres, their innards dangling through the ripped outer layer.

I was bigger than Armin and stronger. Armin was all mouth, that cocky fool. We both knew I could take him out easily. I walked over to where he stood and looked at him up close.

“Let’s do this,” Armin said and jumped on me, climbing on my shoulder. He got me in a choke hold and held me down with all his might. Everybody lined up around us, grunting, yelling, and laughing—Kasim and Vedad in the opposite corners. I steadied myself, not letting him push me down on my knees.

I wiggled out of Armin’s hold and was about to strike him, but Vedad and Kasim grabbed us and pulled us apart. I felt Kasim’s firm grip on my elbows.

“Listen,” he shouted over my head. “You two start when we say.” He shook my whole body as if to reset me and said, “Now you go.”

I was fast this time. I tackled Armin to the ground and shoved his face into the grass. Kneeling on his back, I bent one of his arms backwards and held it tight, twisting and bending it towards his shoulder blades. After a few minutes he stopped wriggling.

The brothers pulled us apart again. Vedad laughed and said, “Man, that was ugly. But fun.”

Gasping for air, I gaped at his wolf teeth. He’d drawn his lips up to his ears.

Armin was in tears. “Asshole!” he screamed at me. “You’ll pay for this.” He ran towards home.

Kasim took the ball in his hands and spun it on his forefinger. “Get lost, nice boy,” he said.

—

Three years later, Armin and I were on the playground again when eight-year-old twins, Mirza and Kenan, saw us from across the field and ran over to our side. They were both dark and so skinny that they looked like two roosters—their noses stuck out like two beaks, their small eyes peered from creased, dry skin. The boys looked like two old men trapped in children’s bodies. They were Roma kids. Their mother worked at the textile mill; their father was rarely around, but when he was home he’d wave at me and smile if he saw me walk by their house. We could never tell the twins apart, but this time one of them had scabs all over his head. His brother had only a few on his neck and elbows. The scabby one was Mirza.

“We want to play too,” Mirza croaked.

“Really, you little toad?” Armin raised his blond brows and smiled. “You want to play with the big boys?”

“Yes, of course,” Mirza said. His brother stood by him quietly.

“What can you give us for it?” I asked. I knew they had nothing to offer, but I liked to joke with them. The twins were dear to me.

“Nothing.”

“How about you put on a nice show for us?” said Armin. “You just have to fight a little, like in the movies.”

“You’re too big for us.”

“No, you chicken shit, you fight each other. The winner gets this ball.”

I looked at Armin askance. I couldn’t believe he’d give them the ball.

“We’re brothers.”

“Brothers fight,” I said.” You sometimes fight, don’t you?”

“Yes, we do. But Mama says if she sees us fighting again, she’ll break our arms.”

“Your mother is getting off work in an hour,” Armin said. “The ball is yours if you win.”

By now, Armin had six soccer balls and counting. His parents had brought him a ball every time they came to visit from Austria. Three years earlier, he had told his grandma about our fight. The day after he told her, I got a whipping from my father. A few months later, after we got over our fight, I asked Armin if he’d gotten his ball back. He shrugged and said he couldn’t care less. He was quiet all the way to school that day.

Mirza looked at his brother. Kenan was still silent. “Let’s do this,” Kenan said and

leaped onto Mirza.

They alternately held each other in chokeholds at first, squirming around like two hungry worms. We pulled them apart. “We’re taking a break,” I said, restraining Mirza from jumping on his brother again. I held him tight in my arms, his scabs close to my face.

“Let them go,” Armin said and pushed his twin into the middle of our circle. I released mine and he lunged ahead. We stepped back and watched them. I glanced at Armin. His lips were stretched into a smile, his foot resting on the ball.

The twins battered each other with their bony fists. Their knuckles found their heads and faces. Soon they both were bleeding. Kenan’s lip was cut open. Mirza’s nose was oozing blood. I ran over to Mirza and yanked him away. The scabs on his head were cut open and bloody too. He left red streaks on his brother’s shirt. They both were crying now. “I’ll kill him! I’ll kill the bastard,” Mirza hissed through tears and blood.

I pulled up the hem of Mirza’s shirt to his face, took his hand, and pressed it on his nose to stop the bleeding. In a calm but threatening tone, I said, “Go home, right away, before I beat the shit out of you.” His brother held his lip and mumbled something about cracking Mirza’s scabby head open. Mirza started running. Kenan scrammed after him. They both ran towards their home, their shirts torn and bloody.

I turned to Armin. His mouth was agape, his lips moving, but there was no sound. I looked down at the ball in front of him. It was unblemished, sparkly white with black spots and a large Adidas sign on it. An intense burn welled up from the pit of my stomach. I sprinted towards the ball and kicked it with all my might. The ball soared high into the broad blue sky.

Things You Left in Accra before Moving to the Bronx

Grandma and her weak leg,

your sister at 18, still with one good iris,

your mother’s British jewelry hidden under the bed,

the places in the carpet you soiled with urine,

all the red dust,

your seat at Calvary Methodist Church next to Marie

who’d always chat with you when someone talked

about Jesus and his power to bring you all the things you needed,

your gymnastic booty shorts (your mother sent

them from America because the heat in Accra overwhelmed

you but you still wish you’d saved some for America’s winters),

warm Tea Bread sold at the YMCA between 6:30 am and 7:30 am,

the scent of air conditioning and ice cream at the SHELL gas station,

Grandma with her good English,

Mercedes and Pamela, your neighbors who borrowed everything from salt to ladles,

Asaana, Yooyi, Aluguntuguin, Nkontomire,

Living Bitters, Mercy Cream, Lion’s Ointment &

a Saturday listening to wind turn on pawpaw leaves.

Two Writers at Alligator Point

Poet, essayist, and publisher Rick Campbell and nonfiction writer Bob Kunzinger have published a combined fourteen books. Campbell’s include The History of Steel, Setting the World in Order, and Dixmont, many poems in countless journals, and for more than twenty years he was the publisher at Anhinga Press in Tallahassee, Florida. Bob Kunzinger’s volumes include Borderline Crazy, Penance, and Fragments as well as hundreds of works in journals and magazines, including several notations by Best American Essays.

Now both have new books from Madville Press of Texas. Campbell’s Gunshot, Peacock, Dog premiered last fall, and Kunzinger’s A Third Place: Notes in Nature in August of 2019.

These two old friends—both writers and professors with a penchant for sharing their wisdom—sat down for a chat about writing:

Kunzinger:

I always found the relationship between poetry and memoir to be closer than either of those and fiction. That’s why I think you find many poets writing essays or other forms of memoir, but not too many fiction writers (though I can suddenly recall many) who bother with nonfiction, or even poetry. I have an easier time reading poetry than fiction because it sends me back into my own senses, and I like that.

Ironically, I’m as influenced by poets as I am prose writers. You’re both, so there’s that. In fact, I enjoy your poetry, for which you are known, but I’m especially fond of your essays—the two in History of Steel are among my favorite nonfiction prose. Who influenced you, do you think? Where are you more comfortable?

Campbell:

I have no interesting answer, no matter how many times I am asked. In poetry, Richard Hugo, James Wright, Philip Levine. I’ve read and liked, even loved, hundreds of poems, but those three poets influenced me the most because I read them first, when I was poetically young. It’s possible that I have been more influenced by Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen and so many song writers than I have poets. I am a listener. For years I have listened to music far more, for far more hours a day, a week, than I read poetry. I hear music and rhythm more than words. I am, I believe, more moved by songs than poems. I am a poet because I wanted to be a songwriter.

Kunzinger:

I think that’s why we are very much the same when it comes to influence, and even a bit with my short prose and your longer poems. We were both musicians at some point—you still are—and the music of our youth was as much our literature as Salinger or Hemingway. For me, early Springsteen, Jackson Browne, Dylan. If I’m screwing around with a longer piece and listen to Neil Young or Browne’s “Sky Blue and Black,” it’s like getting a hit of something that fires me up.

Campbell:

I suppose I am more comfortable as a poet, but identity is a strange thing for me. For many years I think I was better known as a publisher than a writer, and I kept wanting to tell people I’m a writer too. I spend more time thinking about and writing prose than poetry, even though I’ve published six books of poetry and not even one prose collection. I don’t think about poems—I get an inspiration and I write a poem. I never say I’m going to write a poem about ducks or love or something. Poems come quickly, and then it’s over. But I do think about and sketch prose ideas. I have about thirty essays that are finished or nearly so, and it’s taken about twenty years to get this far. If I start a poem, for whatever reason, I write it in a matter of minutes. I don’t bend it or play with it. I don’t even think of it as narrative, as if it’s going somewhere. It’s a bubble that rises over my head like in a cartoon. If I have a prose idea it usually takes longer to be born, but prose ideas go into one box and poetry into another. They don’t get mixed up. Sometimes I might take a finished poem and expand it into an essay, but rarely.

Your flash prose pieces and my longer poems often have much in common. I think your work and mine tends to move horizontally—sliding and leaping from subject to subject. I think it’s called accretion. We layer ideas, but more horizontally than vertically.

Kunzinger:

I am not sure the material is horizontal—maybe in as much as there is some recognizable narrative arc in many pieces—but I think of the tangents within a piece as the real work more than the apparent direction. What’d you call it? Accretion? I tend to think of what we both do in writing as “digression.” I like the digressive nature of some of the pieces—“Flip Flops,” for instance, where the direction of the piece turns out to be little more than a vehicle for the deeper purpose. I think Tim O’Brien does that best, but I think he stole the style from Ernie Pyle, or maybe Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal.

Campbell:

I think I mean that our subjects are layered in a way that one idea isn’t privileged over the others. No dominant idea with the others subservient. Not much hierarchical structure. Your essay “Sliced Bread” does that. When I still used to workshop my poems, I was often told that I had too many subjects. I think that’s not possible as long as I leap and land properly. You and I think in associations and see lots of connections. This might also be why I have trouble finishing essays. Why or when should I stop leaping? It’s a process of montage. a palimpsest, a highway built over a trail, a road that follows a river. Accretion and digression might be the same thing. Tangents, too, but they go toward the essential subject not away from it.

Kunzinger:

I had to look up “palimpsest.” But, yes, exactly. The tangent is the point to begin with. I guess we layer ideas. That’s why I like longer pieces. I can layer it to the point where people will find more to relate to. It is hard for me to do short work. My short prose was developed for the sole purpose of reading to an audience, and some of it has been published, but they were meant to be read in the amount of time it takes to read a two- or three-page narrative poem, so that when I read with poets we’d share the same amount of time. What that did, though, was teach me the art of diction. I reached back to my journalism roots for that and stole from poets like Tim Seibles and Richard Lax. But I’m still way more comfortable in weaving ideas in longer form. That doesn’t mean it always works! Can you tell? I mean, how quickly can you tell if something’s working?

Campbell:

If I finish a poem, then it works. If it fades out partway through, then it’s over. I don’t go back to it. We have music in common and probably also that we never intended to be scholars. I saw my college studies more as vocational school, and my vocation was to write poetry.

Kunzinger:

My vocation is still to be determined. Our “occupational hazard” being that our occupation’s just not around.

Campbell:

Did you ever hear of the JBACC—the Jimmy Buffet Air Conditioning Club? It’s cooler than a fan club.

Kunzinger:

Oh, shit.

Campbell:

Back to writing. I very much give a shit about being read. I like to publish, and I like to have readers. Maybe I don’t care as much anymore about being famous and making it. Does that make us defensive of our work? As in we might still think we have not received the recognition the work deserves? If any?

Kunzinger:

I used to wonder or worry where I fell in the scheme of writers. I’ve published a lot, but I usually feel that is the result of their being not a whole lot of nonfiction writers out there compared to poets and fiction writers. Also, it might be subject-related. I might be the only one writing about Siberia in short form. I don’t know. In the few workshops I have taken, my work was always slammed. I know there are some “subjects” which are going to work and some which I write just for me. But the pieces which get the most attention are the ones that have universal themes buried in some digression. That light went on about twenty years ago when I was at lunch with Tim Seibles and he happened to read something I wrote which I had with me, which is unusual since, like you and me, he and I generally never talk about writing, and he tossed it back to me and said, almost off the cuff, “Don’t show me your pain, Bob. Show me mine.” It was like he flipped on a switch. My writing completely changed then or, I should say, found some new level, and I started not worrying about where I fit in the writing world; I just wrote.

But I can’t avoid the comparison thing. Sedaris still pisses me off. We both did an identical themed piece, his about standing in line at Starbucks and his impatience, and mine—written a few years before his, I might add—about standing in line at a grocery store with no ability to make small talk (“Small Talk”). His stays in the impatient mode whereas mine digresses into memory and something else. How can I not look at the success of his and wonder what I can do differently so the work gets more attention? I simply prefer that first thing we talked about—a piece not be the point of the piece—if that makes sense.

For instance, I love your idea that it doesn’t matter how many “subjects” are in a piece so long as the leaps from one to the other work and the reader lands with us. For me, though, I’ll hit a dead end about, say, geese, but then a few weeks later—or a few months—I’ll be working on the fifteenth piece since the geese one and stumble upon a concept—say people who follow others without understanding where they are going, or the players on a baseball team who spend the better part of their careers on the bench, making a living but ultimately not doing what they planned to do when they were in Little League, and I’ll remember the geese and somehow marry the two.

Campbell:

Richard Hugo wrote about the triggering subject and the true subject; that we need to give up the triggering subject when the true subject shows up. Funny, I think he used geese in his example, too. But as for my insecurities, yes, I still have them. Now that I am older, I tend to worry about the lack of offers I get to headline conferences or compare myself to those who seem to have plum positions in MFA programs. I’m a working-class late bloomer who “chose” to spend his academic/writing life at a small college in a small town. Sometimes I feel sorry for myself, and then I hope I realize that I am doing that and try to get over it. That’s where music, baseball, and fishing come in handy. A poet friend once wrote that I was the best poet few readers had ever heard of. I guess that’s a compliment. All whiny shit aside, I think a lot of my poems and a few of my essays are as good as any other writer’s. I don’t want to be better than other writers, I just want to be good. At this point I should just say “so it goes.”

Kunzinger:

Vincent van Gogh is my inspiration for not worrying about what others think, which can be frustrating when I attend readings where people are paid thousands of dollars, and their work, in my not-humble-enough opinion, is not as good as ours, and our publishing record is so much deeper, and I wonder how the hell do I get gigs like that? Van Gogh painted for himself, completely and unapologetically for himself, to the point where other painters and critics called him a bum and a waste of space in the art world, but he persisted, confident he knew what he wanted to do.

But I still wonder if I’m too simplistic, the writing equivalent of knowing the three chords from which you can play any pop song. It is popular, but it has no staying power. And I fear I finish too soon, in the piece I mean, not time-wise.

Campbell:

Finished is a weird thing. I say a poem’s finished when I feel it’s as good as I can make it. Then I might let it sit a little while longer before I think it’s ready to send out. But the essays baffle me; they are harder to finish, maybe just because the more words, the more possibilities. My real problem is that I forget that I have essays to send to journals. Even if I spend the good part of a day sending out poems, I will forget to send out the essays. Is this some Freudian lack of confidence? Did Freud ever talk about this? My knowledge of Freud is just some shallow pop-culture reading.

I was never diligent about sending work out. I also know that I have never worked hard enough, never hustled enough, to garner fame. I don’t work as hard as you do. I respect how much you write.

Kunzinger:

Yeah, I am better than you. [Laughs.]

Campbell:

This is my virtual porch.

Kunzinger:

Seriously, I still hesitate a long time before actually sending something out. I’m always fighting the triteness. I have to go back and “get the trite out,” as I like to think of it. That reminds me of the idea that Rupert Fike told me once that an ending must both be a complete surprise and totally obvious at the same time. I’m okay with ending. No, for me, it’s when I start that I struggle to find something familiar but not at all trite. I can conceive an essay okay. It’s not unusual for me to stumble across one moment in my day, maybe in conversation with someone, or something I overheard in a hallway somewhere. “Flip Flops” started like that. The piece all hangs on one line the doctor said to me at a check-up: “It’s a good thing you whacked your ankle.” I had no idea where I was going in a completely separate piece about 911 until that line, and I joined a stale work with a new direction. Sometimes, though, the direction is so obvious.

Campbell:

When we are nonfiction writers, we promise to tell the truth as well as we can, given the limitations of memory and vagaries of time, given the influx of new information. I am thinking about when you found out that you had Italian ancestry and then saw your “new” family name on a building in Tampa. Actually, I think I saw it first. Discoveries like that change what we know and maybe what we have written. But poetry is neither true nor false, not fiction or nonfiction. I mean it is or can be one or the other, but there’s no rule, no category. There’s no nonfiction shelf for poetry. And yet readers, despite often having a high level of poetic sophistication, assume that a poem is “true.” They want poetry to be autobiographical. Most of my poems are, and I assume that lures readers into thinking that all of my poems are true. I guess that’s the readers’ problem not mine.

Kunzinger:

If I’m reading or writing journalism, I expect absolute adherence to some form of objective truth; that is, verifiable information. But as a nonfiction writer—which is such a huge term covering everything from personal memoir to documentaries, and as a term literally means, simply, “What I’m writing is not fiction”—I find a massive gap can exist between “truth” and “accuracy.” In my Siberian essays, I can guarantee—that is prove—the “truth” of the pieces in that I was on the train with my son heading east toward the other side of the country. The people I met are all real, the stories of almost missing the train, as well as the floods on the Amur River, are all real, but I can’t guarantee accuracy. I don’t remember the conversations word for word or if they were in the day or at night or sometimes exactly which station we were at when we bought dried fish, but the essential narrative, a father and son traveling across Siberia together, sharing these experiences, is true, because that is the point of the piece; I’m not writing a guidebook.

I was reading some of your unpublished essays and I was not concerned with how accurate you were as to which highway you were on—I’m never going there—or when it was, and even the details of what happened; my focus was on the truth of the “spirit” of the places, and the nonfiction elements of remembering. Poet JT Williams described my work as, “This is a bunch of shit that happened to you and how you best remember it all these years later.” I think that’s an accurate definition of the truth. Tim O’Brien still has the definitive explanation for “truth” in insisting something that “seemed” to happen is often “more true” than what really happened, even though the accuracy might be questionable.

Campbell:

What I find interesting is trying to tell the truth, to be honest, in nonfiction. I write a lot about how what I remember might not be exactly what happened. I try to be honest, try not to lie, but it’s clear to me that capital-T Truth is often not attainable.

You are more of a nonfiction writer than I, and you were trained in journalism, so how do you feel when accuracy and truth prove to be elusive?

Kunzinger:

I do my homework; I try and unearth the validity of what I’m writing, but if I keep reaching various “truths” because the foundation of what I’m writing is already subjective, I let “accuracy” go and just lean back on personal take.

My Siberian work takes place in Siberia, but it is about fathers and sons, about sacrifice and journey. It was the ultimate metaphor—my son and I on the same train going the same distance across an unknown wilderness, and his perspective is different than mine, which I tell through letters to my father. That isn’t a travel essay, I don’t think, nor is my work on the Camino or in St. Petersburg. If someone asks me what I write about, I don’t think of myself as a travel writer—the new book from Madville, A Third Place, is about nature, but it isn’t a guide. Ian Frazier and Colin Thubron both wrote extensively about Siberia and, honestly, their books aren’t guides either. That is why I left journalism. A journalist would write a guide; an essayist such as myself writes about the spirit of place, and a poet, well, they just ride the train into the distance and someone else writes about their death. That’s Russia.

Campbell:

I agree completely with your take on your writing: your memoirs are framed by travel. Travel is, metaphorically and spatially, your vehicle.

When my essays overlap with my poems, it’s almost always that the poem came first. Sometimes years before the essay. Those poems are often more narrative than lyrical (though I don’t really believe in or understand a hard distinction). The poems are condensed, and the essays are expanded, but the subject is the same. Sometimes it’s a travel topic but more likely it’s about family. Family is such a twisted and complicated subject that the poem, even a series of poems, just sometimes does not allow me to say what I want to say. There’s an essay that was in The History of Steel (and first in Kestrel) about my father’s death that is clearly an expansion, or a gloss, of a shorter poem from some years before.

I like to make a distinction between true and honest. I want my work to be honest—either as true as I can make it, or an honest attempt at accuracy. And, yes, the spirit of the work is the most important element. Still, I do like to get the highway numbers right. I have an essay, “On Not Going to Vietnam,” in which I claim this guy I met got #2 in the Vietnam War draft, went to war, and might have died. I accidentally found out twenty years or so later that he did not do any of that. I was being honest, though, it turns out, very, very inaccurate. The last part of my essay explores how I might have come to believe these inaccuracies, but I can’t even explain that.

Kunzinger:

When we discuss memoir vs. travel essays, we both seem to lean toward the memoir side, and the sense of place is important, but only in as much as it serves as a foundation for something else we respond to. A Third Place is a compilation of short essays, mostly in nature, but not about nature; most of the writings—particularly the digressions—were not conceived together. I heard an interview with Billy Joel, and when asked about “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant,” he said the three different parts to that were written at three different times and none with any thought to being connected to the others. It was only later that he found a common thread and tied them together. I write like that. So if I “finish” a piece about missing a train in Russia, I already know in the back of my mind I’m going to write something else later, or maybe already have written it, that at some point I’ll realize would make a good fit for it, and then go back and tie them together or, sometimes, lace them. Often, I find the “truth” of the piece later, after the bulk of the “narrative” is complete. When you found the truth about the dude who didn’t go to Vietnam, it sounds like you thought you needed to explain yourself to the reader, like some Waltons epilogue—“Mary Ellen eventually moved to Richmond and is living as a prostitute.” I think what really happened to the guy not going to Vietnam is irrelevant—in that essay anyway. Maybe another one later will be solely about that. Tim O’Brien does that. I love reading his essays which later became parts of books—like those in “The Things they Carried.” If you read them carefully you see some significant differences between the original essay and the form it took when complied with other essays which he wanted to somehow connect. I see that in your work too.

Campbell:

Did I ever tell you my O’Brien story? It’s the late 1980s, and my friend and I drove up to Augusta, Georgia, to hear Tim read. We didn’t leave till after noon, so we had to bust through rural Georgia. We got there just as he was being introduced and made a commotion by trying to come in quietly. My friend Judith Ortiz Cofer was hosting the reading, and after Tim was done she took us up to meet him. I was worried about how road ragged I looked, but Tim, as always, looked just as ragged. As we were talking, a man came out of a room behind us, and Tim says, “This is my friend Kiowa.” I just stand there looking dopey and then say, “Man I thought you were dead.” Kiowa shakes his head and says, “It was fiction.”

O’Brien intentionally blurs the line between fiction and nonfiction, and he certainly twisted me up. We have yet to mention the New Journalism. As in Norman Mailer quoting the inner thoughts of Gary Gilmore that he could not have possibly known. Mailer, Truman Capote, Tom Wolfe changed what we can say in nonfiction forever.

I used to tell people that I didn’t write fiction because the only character I am interested in is me. Then I blew it and published a short story about a kid nailing his father to a cross. I didn’t like my father, but, God, I never crucified him.

Kunzinger:

I have no fiction DNA; it’s that simple. Tim first wrote If I Die in a Combat Zone, which is the nonfiction predecessor to the stories in The Things They Carried, which he wrote about twenty years later. I can’t even pull that off. I was in a fiction seminar once with Sheri Reynolds, and we had to write a fiction story—I wrote about a twenty-four-year-old who worked in an exercise club and the people he met, which is completely me. It sucked. When we went over my piece, the other people in the seminar crucified me!I left and drank something like four margaritas that night.

Like now. See, this is why I hate talking about writing. I just remembered just how bad I can be at it. Dammit. Let’s get some oysters. Damn. Let’s get some beer.

Summer III

Across the forest, we sit

in a deer stand shaped like a heart.

A cry comes from the center of the woods

like wind blowing through a doll’s head.

There are birds that come out at night

just to be devoured by other birds.

I can’t make things happen faster

than they’re going to happen.

I know that now.

If your thick arms come out

of the shadows only to light smokes

or hold my hand expertly in yours,

I need to accept it.

when I stopped fearing ghosts

I learned about ghost hunting from my mom. When I was in elementary school, she drove me down to Louisiana every summer, and we’d stomp around the boggy summer heat in old cemeteries, reviewing etched tombstones, trying to find the names and death details for her ancestors.

We slogged through swamps, heavily forested areas where the heat bugs hissed so loud, I could barely hear when she called to me. We went all over the state—Mansfield, Baton Rouge, Grand Chenier. We stayed with friends in between, drinking sweet tea and eating collard greens, cornbread slathered with slices of cold butter. I was never quite sure what my mom was looking for, or why we needed to find it out there in the heat.

My mom was bad at picking up on things. That’s why she didn’t notice at first when a spirit latched onto her one summer in Louisiana. It just slipped out of the gravestone and sunk its claws into her, like a bad smell. The thing held tight to her all the way back to rural Vermont where we lived. I didn’t notice it at first. But then, a month or two later, it made itself known when she and I were alone at her office building one night.

The office building where my mom worked was four stories—a first floor, second, an attic, and a basement. I hated the second floor. It was dark and full of offices, crowded and narrow. Whenever I stayed late with my mom, I lingered on the first floor in an open office space, next to a large row of windows.

Sometimes she worked upstairs, and that night, she was working out of her boss’s office when I went upstairs to ask her for food money. It was dark, and the lights were off in the hallway. “Mom, can I get food money?”

“For what?”

“I want to go across the street.”

She hesitated, then rustled around, appearing in the doorway at the other end of the hall. There were at least five doors between us—five different offices along the hall. Some were open, some partially, one closed. I stood at one end of them. My mom was at the other. We looked at each other for a moment, and then I got the sense that something was wrong. I remember my skin prickling, like getting goosebumps in the cold, and then one of the open doors slammed shut.

My chest tightened. I felt the fear in my chest before my brain could register what happened. A second later, I went running for my mom.

+++

Twenty years later, I move from Vermont down to St. Pete, Florida, seeking the heat of my childhood. I get a tiny studio apartment and a new job working in development at a legal aid firm.

My ex-boss from Vermont texts me once a week. I keep the selfies she sends me saved in my phone and look at them when I miss her. I’m still in love with her, even though she’s married now, and I’ve moved two thousand miles away. In her texts, she tells me I’m pretty. She asks about the grants I’m writing at my new job, the beach, my friends. You’re pretty AND smart, she says, when I send her a selfie at my office. Her paragraphs always include winky faces. She doesn’t say much about herself.

After settling into my new office at my new job in St. Pete, I decide to decorate my desk. It’s black and chic and empty, so I print out pictures of me with my four best friends and tape them up on one of the monitors. There’s an empty space at the bottom. I leave it for a day, then print one of the selfies Lauren sent me and tape it up.

Back when I worked with her, Lauren and I spent eight to ten hours a day together. We went on field trips—to Stowe, to the islands, to happy hours. She told me once, on a longer trip, that things weren’t so easy for her as a child.

“But you’re so good with your dad,” I said. “You guys are like best friends.”

“It wasn’t always like that.”

“What was it like, then?”

Her mouth tightened. She was always doing weird things with her mouth – pursing her lips, parting her lips when she concentrated, these uncomfortable, awkward things that I loved watching. Sometimes, I felt her face moved on its own, like something else was guiding her that she couldn’t see or understand. “One time my brother and I were fighting, and Dad came up and,” she gestured with her hands, “wham. Knocked our heads together.”

“What was it like with your brother?”

“We hated each other,” she said. I asked why. She told me he could never forgive her for something. I waited for her to tell me what. She never did.

After two or three days of having her picture up at the office, I take it off the computer monitor and tuck it away inside my desk. I don’t look at it often, but sometimes, when I get out tea to brew, her face will come into view—the blonde hair, the freckles. Every time I see it, I think about those months I spent listening to her plan her wedding, talking about bridesmaids and dinner menus. I think about all the times I cried in the bathroom. How her face tightened when I told her I liked her. How inferior I felt standing next to her fiancé. How she looked at him like I wasn’t even there at all.

Yet every time I get close to throwing her picture away, she’ll text again.

I miss you, pretty, she’ll say and send a new selfie. I hope you’re enjoying your new life.

+++

The ghost that followed my mom home wasn’t malevolent, but it liked attention. It tapped on the walls at her work when she stayed late with me, large knocks on the plaster, as if someone were stuck in there from the other side. It ran up and down corridors and through the hallways. It smelled like cigarette smoke. The scent would balloon out, linger, then move. I’d sit there alone at night and all of a sudden the scent would creep up, eerie as a cold night wind, slipping its arms around me.

The next year, I started staying home alone at night instead of going to work with Mom, and the sounds disappeared. The spirit went away.

“You didn’t hear from her?” I’d ask my mom, day after day.

“Nothing,” she said. “Must’ve gone home with somebody else.”

I thought about the ghost off and on, wondering where it went, but as I grew, my interests diverged outward, and I thought about it less and less. Other things began taking up my time—basketball, grades, friendships.

In the seventh grade, I fell in love for the first time. Gina was short with long hair and a crooked smile. She was also my biology teacher. I hung around with her after school every day, and she paid special attention to me. I thought it was because she loved me.

It wasn’t until later that I found out she had a sexual relationship with a boy only a year older than me. She was fired immediately and, in the following months, lied to me repeatedly, begging me to help her get her job back, telling me she loved me. She missed me, she said. She asked about school, about sports, like nothing bad had ever happened.

After months and months, I stopped emailing her back. It hurt to be in contact with her. I felt creepy and weird, and thought there was something wrong with me for loving someone who’d done something so bad.

Still, even after cutting off contact, I thought about her. My thoughts eventually became less about missing her, and more about trying to understand what she had done. Why had she done it? Why did she lie to me? Why did she pretend she cared?

That’s the part that haunted me. I thought she loved me like I loved her. But she never really did.

+++

After I finally stop talking to Lauren, I go on my first date in over a year. I walk downtown in a button-up shirt and skinny jeans, sweat pinching under my arms as a cool breeze snakes in through my shirt sleeves. I’m early, so I grab a beer across the street at a local gay bar and watch the crowd around the coffee shop across the street where I’m supposed to meet my date.

We’ve been talking for a few weeks now, and I really like her. She’s in her early forties, and a therapist. She communicates well and gives me space when I need it. I like her boundaries and her maturity. I like how she looks and what she does for a job and how giving she can be.

I spot her walking in and finish up my beer, then head over. She recognizes me immediately and opens her arms for a hug. We sit at a porcelain bar, and she orders a fancy coffee while I get a beer. We make small talk at first, then ease into a conversation. I try to keep my mind on the present and not the worries burbling in my stomach. Everything seems to go well. After two hours, she heads off to a dinner with her friends. I visit a friend, too, at a bar down the street, and we talk until it’s pitch black outside and the wind gets too cold for sitting outside anymore.

It’s on the walk back that I start to panic.

This woman is beautiful, successful, and healthy. What could she possibly want from me? I worry about what I said during our date, how I acted. I worry I’m going to end up liking her too much and then she is never going to like me back the same way.

After crawling into bed, I start to cry. The wind is strong and cold in a way I never expected Florida to be. I stay huddled in the blankets, my face pressed to the pillow.

I didn’t stop dating just because Lauren broke my heart. I stopped dating because it’s just too hard. I can’t like someone without immediately wondering how they will hurt me, like Lauren hurt me, and Gina. It’s been fifteen years now since she was fired, but she still pops up sometimes, slipping out somewhere from the shadows, this little voice telling me that she is going to leave. She is going to hurt you, like all the women you love. I don’t know how to shut it off or make it go away.

+++

After leaving Vermont, I spent five weeks on an “art farm” in rural Nebraska to work on my writing. There, I learned how to install drywall, build survival fires, and cohabitate with field mice. The house I lived in was more than a hundred years old and had been transplanted to Nebraska without its foundation, then built back up into something that could stand alone.

The bones of the house had potential. They were wood, weathered and old, but with moments of stark beauty. The house was slightly crooked, too, and with the additions that had been made on the western wall, it looked like it had a face—two eyes, a nose, and a zippered mouth.

When I first arrived, I was terribly uncomfortable in the house. There were too many people there, too much going on. But after it started getting cold, and everybody left, I transferred bedrooms and began liking the space much better.

I started noticing the phantom noises during the afternoons. I’d sit downstairs in the kitchen drinking tea and writing, and I’d hear footsteps above me. My roommates had work studios elsewhere, and I was alone. I’d call out. Listen to the silence. Then it would start up again. It went away when my roommates were there, but on several occasions when I was nestled in bed, I got the distinct feeling there was something else in the room with me, standing at the edge of my bed.

One night, I had a dream that I was a little boy away at a boarding school in Greece. I saw everything from his perspective—the cliffs above the sea, white foam crashing, the old school uniforms, the sunlight. I’d never had a dream from someone else’s perspective before. I told my roommates about it the next morning.

“Could’ve been a past life dream,” one of them said.

We all sat downstairs, sipping tea and coffee as the sun burned in through the windows. The smell of buttered toast hung in the air. “Or it could’ve been a memory from someone who died in here,” the other said.

I went about the remainder of my time in Nebraska believing there was a lonely child ghost in that house, just looking for a friend. I played music in the afternoons to cover up his stomping. Before I went to bed, I said goodnight to him. I told him to rest while we were all asleep.

Nebraska was where I stopped fearing ghosts. Nebraska was also where I unfriended Lauren on Facebook because I couldn’t stand to see any more of her wedding pictures. It was where I cried in my sleep, and dreamed about her, and tortured myself wondering what I had done wrong, what I could’ve done better to make her love me.

Most days, I woke up scared she would text me something about her new life with her new husband and I’d have to pretend, like I’d already done for a year, that everything was fine, and it didn’t tear me to shreds. Most nights, I went to bed afraid I would keep Lauren inside of me forever.

+++

A week after my date in St. Pete, I dream I’m living in a haunted house. It’s a large mansion with thinly made plywood on the outside, but with grandiose, Victorian-style decor on the inside. I go from room to room in the house with a feeling of dread at the back of my neck. I know something’s behind me, but I don’t want to turn around to look. The entire mansion is riddled with shadows, and I keep throwing open the curtains only to have them fall shut again when I move away.

Finally, I realize I have to go. I can’t stand it anymore. I pack up my car with all my things. I place some stuff on top of the car, twining rope around the door handles to keep everything in place. I hurry. I can feel the thing behind me, to the side of me, all around me.

After getting in the car and starting to drive away, my tension begins to ease. I look around at the trees. The pines hang low, their needles brushing the windshield as I drive.

Suddenly, the car engine sputters. I know then that the ghost is still with me, even though I’ve driven away. It’s hanging onto the car, trying to keep me from getting away. I fight with the stick shift, but the car slows. I’m driving downhill and hope the momentum will keep me going, but then I lose control of the steering. The car fishtails. I take a turn into some bushes and then for a second, it’s all green and moss and branches scraping at glass. At the end of the underbrush, my view clears. I’m at the edge of a cliff. Rocks kick up under the car. Panic grips my chest, but there’s nothing I can do. It’s too late.

I open my mouth to cry out and then I’m airborne, soaring over a hundred-foot fall, a rush of rapids waiting to devour me below.

+++

I wake up in the morning with that familiar feeling—that something else is in the room with me. It’s never happened in the St. Pete studio before, and the sensation is slightly different than it was in Nebraska. This morning, it’s more like this thing was with me and, as I woke, it slipped away.

I rise and make the bed. Shower. I bustle around in the tiny space, heating tea and stir-frying potatoes and eggs with onion and pepper. It’s cool out, and the sun peeks in through the blinds, falling in strips across the kitchen tile. I don’t have the sense of anything lingering anymore. It all faded as the sleep washed away from me.

My childhood was all about finding ghosts, about hunting them, and understanding them. I never learned how to get rid of them, though. It seemed like they were always just there, until they decided to go away, or I left wherever they were haunting. I want it to be like that with Lauren and Gina. I want to just wake up one day and they’ll both be gone from me.

That morning, I think a lot about my time in Nebraska. I think about how calm I was in that house, even knowing something else was there with me. I remember the cold mornings and the afternoons when the sun shined in, warming my cold feet. I remember turning the light off at night and looking at the outline of the room, my vision blurred without my glasses, dipping over rounded spots and shadows. “Good night,” I’d say to the room. “Rest now, so we can all get some sleep.”

The Funhouse Mirror of Humanity

The Internet Is for Real

Chris Campanioni

C&R Press, 2019

534 pages, Paper, $25.90

Imagine the internet told your life story and fucked it up. That is the unspoken thesis behind Chris Campanioni’s The Internet Is for Real. Although it becomes clear early on that, while Chris will spend time discussing his family history and other autobiographical details, the life story he is really telling is that of the modern world, as filtered via internet culture. His work views the internet as humanity’s id: sometimes charming, sometimes profound, but mostly idiotic, vain, and vapid. While large portions of the book are dedicated to celebrity worship and the distracted nature of internet communication, he also turns his attention to the way our political past and present has been affected by this new technology. A winding discussion with his father about his relationship to his native Cuba after fifty years melds into a meditation on dreams versus reality versus nostalgia, the distance between his father’s recollection of his youth becoming a cipher for Campanioni’s own distance from his father’s homeland.

My father dreams in Spanish. I am writing this down in English.

Where are the gaps and slips, I wonder, as I hold the tape recorder with

my left hand, and with my right, scrawl the notes that will eventually

re-constitute this story.

Where are the gaps and how can I make them wider, instead of trying to

fill them; how can I make them wider so I can breathe within them, in

and out, out and in, and make song from all those unknowable breaths?

He recognizes that the memories and dreams he uses to feel a connection to his ethnic heritage are for a place that no longer exists, that may have never existed, but one which he cannot escape. This could very well describe social media, where we hold on to, document, and obsess over memories and the image of ourselves those memories conjure. The way people communicate with us on social media is through a manipulated, nostalgic view of ourselves that polishes the rough edges of our personalities. In turn, complete strangers come to relate to us in the same way the child of an immigrant relates to the memories of their parents’ homeland—we know it is a myth, but we can’t bring ourselves to ask the tougher questions that arise from that myth.

Another instance where Campanioni uses the internet to make larger statements about world affairs is his chapter on ISIS as an online creation. The piece is a tour de force that demonstrates the way that terrorist groups can promote themselves using the same sort of branding and merchandising as a clothing line or television show. A new video of a beheading, for instance, is treated the way the new trailer for a Marvel movie might be. The violence is a show, and, for people seeking meaning, a global conflict is incredibly appealing, as is the hierarchical society offered by ISIS. This impulse for meaning and fighting for a cause is as old as humanity itself, but because of the internet a cause can reach an unprecedented scale by utilizing the tools of consumerism.

YOU

Senior media operatives are treated as if they’re emirs.

ME

Emirs?

YOU

(sharply)