I got the call from Liam just before dusk, and the sun shut down by the time I made it back to Times Square, to that bar with the tiny sagging stage, where Liam and I stood waiting for the first joke, Short, the six-foot-seven owner of the club who had pink tattoos and a mean resting glare. (This is a comedy club? I’d asked Liam when we’d walked in days before. No, it’s a comedy cellar, he’d corrected with a smirk.) Short had been the one to call Liam, and the point of their conversation was that none of it could wait, that coming back was urgent. “Urgent” was the word I’d have used to describe the conversation I’d been trying to have with Liam for months, a conversation he had avoided with some real talent before we took our seats in that same cellar days before. For a moronic moment I thought the whole reason I was back in this place seventy-two hours after drunkenly yelling You’re not David fucking Sedaris! in the post-punchline quiet at the man I claimed for sixteen years to love was to turn back the clock and find a way to save it all. To save us. To follow Liam to the broken plate of our relationship (which okay, I had thrown), and put it back together so I could keep laughing at his archive of jokes over dinner, which were somehow both colder and deader than whatever discount bass he’d brought home from the market.

“It’s the footage,” Short said. “Come on back, I’ll show you.”

I waited for Short to walk out of earshot, his head ducking under a low partition and into the other room. I looked at Liam, who looked away.

“Do either of you need anything?” Short yelled. “A drink?” The real joke, and I let myself laugh.

The back had the feel of a photo darkroom—just enough light to see, the caustic smell of something like bleach making it hard to breathe and harder to focus on the small television monitor Short was looking into, the pixelly blue glow of it on his concerned face. I had spent the entire train ride down to 42nd avoiding the idea that I was obviously the one to blame, which had begun to metastasize out of nowhere, blunt and irrefutable, into a fact.

The video showed the audience, and sure enough, there were Liam and me, at a table in the far corner. After thirty seconds, I heard Short inhale sharply and pause the tape.

“There,” he said quickly. “You see that? On the wall—”

Liam gasped.

“I don’t see anything,” I said. I had been intently watching myself, my face, to see if it gave away my disgust about midway through the set, catching the petering trail of laughter after a few efforts at a punchline.

“Watch the wall,” Liam said. “Rewind it, watch the wall.”

Short cut the footage back fifteen seconds; I watched the wall. After a few deep breaths, in the clip, three white marks appeared over our heads, clawing in jagged lines up for a few seconds before turning a blood red hue, then vanishing.

I looked at Liam. “Do you remember this?”

“I was right next to you. I didn’t feel a thing.”

“What do you want us to do about this?” I said, turning to Short, who held one hand over his mouth, though his demeanor was oddly calm, as if he might have realized it had been nothing at all.

“Well, we saw what happened afterward,” Short said. He cut forward on the clip. “It doesn’t come back. The marks I mean. But a few lights burned out. We caught it because we were gonna put it online, the show.”

“Sorry, what?” Liam and I said, in different iterations.

“We were going to, and then we saw this, so we’re not going to. I want to know what happened the rest of your night.” Short sat back, then stood, his head hitting a hanging bulb; its flicker made us jump. “If this place is haunted we aren’t renewing the fucking lease.”

Short clicked off the small television with a fresh expression of concern. What had happened later that night, moments after those marks, was coolly blurred by the martinis the host had served, one after another, and only barely memorable now: the speeding cab howling up the interstate alone, the high pop of a cork echoing quickly in my kitchen, and somewhere among all of this, or between it—before it?—whatever lines I had said, the point of which were that I no longer loved Liam, that wasn’t it time to get honest about our lives, and give up the act? Give up the act was the phrase that hooked on me as I had uncorked that old bottle of port, a sickly sweetness sliding down my throat, like sugary blood. And later that night I was sleeping so well, but when I turned over in bed, my arm had reached instinctively for Liam and landed on a pillow, startling my body awake. As if I’d encountered a ghost.

—

I had moved to the West Village with Liam halfway through our twenties, in a middle-of-the-night stunt that I felt would change us. And to seem like the kind of people we in truth already were back in Western Mass: well-off, well-dressed, well-poised to, on any given Friday night, blink and find ourselves among affable investment bankers and lawyers and their children, whose idea of danger was wearing white pants to a catered fundraiser they playfully called a barbecue.

I did not return until nearly sixteen years later, after my father simply stopped breathing in a reclining chair after drinking one too many bourbons, heart racing from one too many arguments. What I’d heard from a family friend, the pitiful gossip, was that his brain had gone to dementia, and he’d spent the last few years spinning family histories, weird, incoherent stories about his grandparents; his death was a shameless relief, the small home he had left me a burden.

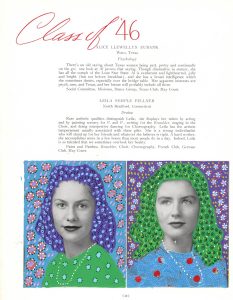

After a long morning drive north, Liam and I stood with a man named Greg, whom we’d hired to help with the take/toss for my father’s rusted shovels and peeling horseshoes, whose dumb obliviousness to our gayness made him seem vaguely bisexual. The oil paintings had been done on expensive white canvas and fell with a loud wooden clatter to the ground when I first pried open the old door to the shed in my father’s backyard. Liam took each painting out of the shed and laid it very gently in the grass, a few dozen squares gridding the lawn. Greg took hold of a wheelbarrow in the back and made a surprised “oof.”

“Unlucky guy,” Greg remarked at the carcass. He screeched something metal along the floor. “Raccoon, maybe possum. When’d you last get in here?”

“Few years,” I lied. I’d last been in the shed as a child, when I caught my finger on one of my father’s deep sea fishing hooks, bleeding a line of red to our front door.

The gallery of paintings growing on the lawn—their swirling browns and blues, psychedelic neon reds splashed across cream, the loud pops of yellow like splatters of blood—puzzled me. My father decorated his bedroom with heads of bucks mounted on the walls with rifles and flags. There was a long pause, punctuated by the sound of Greg sweeping up the remains. A pigeon shit on a shingle. For a while, I tried to let the purging register as cathartic, but ultimately I felt nothing. It was like helping a friend move from one side of town to another, if that friend had decided to cut out the hassle of propping their life back up someplace else.

“These all say LT, in the corner,” Liam said. He squatted to the ground, eyes flashing from one painting to another. His body registered the name, shocked alert. He looked up at me. “Oh my god, Mark. Laura. Your mom did these!”

—

The next morning I shuddered awake, as if shaking something off me. I washed my hands. I avoided my reflection in the bathroom mirror and then stared intently into it, two bulls locked by invisible horns. I called Liam and hung up after one ring, two rings. I texted him to be sure he knew it was an accident. I waited for him to reply. I asked him if he had noticed anything strange. I watched, from the window, a man dressed in a tuxedo walk slowly into the foggy park. I tried to make sense of this. I waited for the man to return. I sat down on my bed and noticed a long scratch on my arm. I panicked. I made a note of every trio of things in my apartment, which held their haunted charge. I became suspicious of soup bowls. I vigorously cleaned my counter and sink. I drank a bottle of cheap, caustic wine. I wrote a note apologizing to Liam and dramatically burned it with a lighter, the flame singeing my fingertips. I called Short at Comik. I listened to him tell me he was scared. I missed Liam terribly. I missed him with an addict’s love, in a way outside my own body. I sensed myself cooling, like ice. A knock came at my door—a young man holding a handle of vodka, looking for a party. He apologized and left.

For a long while I stood at the sink, my face unrecognizable in the shining metal, and then I slept on the couch. I knew Liam wasn’t coming back.

—

Twenty-three paintings, stacked neatly in the garage. As Greg pulled out of the driveway for a last haul to the garbage dump and we both sat down to a discount lemon cake for Liam’s thirty-fifth, Liam asked which I wanted to take. The question felt like a test. What I wanted Liam to know of my mother was what I knew: almost nothing. She was sweet, and motherly, in what I could remember of her. It seemed like a lie, that this was all I could recall. There had to be something more, underneath so much else I did not know either. Clues under clues, and all I had were a few photos in their silver frames, tinted slightly with age.

“Keep the blues, the quieter ones, the forest green?” I asked him. “The others are so loud. I still doubt she did them, by the way.”

“LT,” Liam said, communicating again the obviousness of the attribution.

“Anyway, I vote blues, maybe greens.”

“They’re nice,” he said.

“You don’t sound impressed.”

“I have secret hobbies too,” Liam said.

I’d later learn the secret hobbies included hoarding VHS tapes of old standup comedians’ late night sets, which played with a fuzzy static so many years later behind the confession that this was what he wanted to do: pursue comedy. When it finally came out of him, it was in this seriously unfunny way, so desperate it nearly made me laugh. The pursuit of anything held the edge of the ridiculous. In that kitchen, Liam embodied the pitiful warmth of someone who thought I was on his side, who would let us grow together.

I rejected the playfulness by asking about the cake. Liam said it was fine. Greg showed back up with his empty pickup, and we took three of the paintings with us—two deep ocean blues with fine gray lines as if to indicate breaking waves, a green with translucent ovals, a forest seen through raindrops—clacking against each other as we began the hundred miles or so back to the Village. When we got home, I couldn’t sleep. I walked to the kitchen and took a slice of cake from the fridge. It was awful, and when I went to spit it out, Liam was behind me, his eyes closed in sleep. As I dropped the plate, he woke from a trance. He hadn’t sleepwalked before, or since. We went back to bed. Liam lay awake as I regarded the fine waves, rising in their dark block from the corner of the room, until I could smell a salty breeze, until I felt the sun shimmer sweetly on my closed lids, until finally, at last, I slept.

—

Liam and I met our first day at Granite High, a collection of brick buildings that at night resembled the hospital both our dads worked at, without the orbit of screaming sirens or freak deaths from the nearby ski resort. Liam was shy in an easily ignorable way, and we successfully ignored each other often: during phys ed and pre-calculus and lunch, but both found ourselves in the same mindlessly easy home economics class junior year, taught by a jittery, white-haired woman named Suzie who frequently stopped class to talk about a summer in Paris that seemed to exist outside of time. The elements were almost absurd in their inconsistencies. The selection of Paris was the sort of desperately romantic lie you really couldn’t help but pity, and Liam got to making various references to his Parisian upbringing whenever Suzie was within earshot, testing the limits of her patience.

“These cookies remind me of the croissant I had on the top of the Eiffel Tower,” Liam said one day while stirring a bowl of over-floured dough, powder spitting from the bowl with each stir. “That time the wind blew off my beret onto the Louvre, and I was wearing black and white stripes for no reason.”

I only joined him in detention to ask him if he ever got the beret back. He told me it was run over by a wheel of brie. It felt as if I’d met someone entirely new, and later that day, we stood next to each other washing our hands in the bathroom, avoiding the dangerous desire we eventually confronted the night after prom the next year. College together, the same dorm, down the hall, roommates, all the late nights with pizza and cheap vodka that burned our fingernails and turned our eyes bright red. And then the day after that Liam was stepping out of the shower and asking if I planned to make the bed before we headed down for his set at Comik.

Sometimes, when I was in a good mood, I told him I couldn’t hear him from across the Atlantic.

—

A week passed since that night with Short, without Liam, and each time I began to forget, or heal, or complete whatever transformation was required of me to get from life with him to someplace where this was all behind us, something appeared, briefly and cruelly, to remind me of his gentleness, his sweetness, his love of ducks and the color purple, the way the subway doors shut so suddenly they can trap you in their grip, as they’d done just years ago with one of Liam’s leather photo bags, dragged down to Soho exposed to the dirty, frozen air. My heart spun back days, or weeks, a stranger to the breeze outside my apartment, the snow falling on the familiar trees.

I opened Liam’s bedside drawer one night to discover The Standup Standup, an annotated paperback guide to becoming a comic. I tore ravenously through the different steps one is meant to take to find themselves as a comedian. Again and again the author advised that the whole point of any joke is to flip expectation, as extremely as possible. Most of the advice to this end seemed to boil down to various broadly applicable platitudes, but Liam’s earnest notes suggested he took the text to heart. Most interesting to me, though Liam hadn’t marked any of it up, was the glossary, all these terms. A “roll” was when a comedian delivers jokes in rapid succession for sustained laughter, a “topper,” alluding to and building off a previous setup that itself had to be assembled with just enough strength to be memorable, without requiring extensive explanation. The “first story”—what the audience imagines based on a joke’s setup—and the “second story,” what they see after the punchline, when the joke is complete. I presumed Liam had not noticed the glossary or felt it was not of great value. He had scrawled the beginnings of presumably original material on the margins throughout the chapter “Getting to Know the Comic in You.”

I was driving down the interstate and I saw a [illegible]

New York apartment prices [crossed out]

And then:

My ex’s mom was a painter, let me tell you something about painters

—

The lemon cake disappeared from the fridge, which we forgot about easily enough. It seemed possible one of us had disposed of it, just tossed it, unthinking. But then came the nightmares for Liam, of hearing dirt fall over the thick wood of a coffin, of waking in a cold forest of pines that glowed with low, white mist when he walked. His dreams, as I began to refer to them, seemed to possess a certain unspeakable vividness that made me uneasy.

We set the paintings on the curb one night. By morning his visions were gone, and so, by lunchtime, were they.

—

And I had begun to think of his friends. Liam’s closest was a psychic and medium whose string of messy relationships Liam had occasionally disclosed. I’d met him several times, despite frequent efforts at avoiding him—Adaem, lanky and spikey-haired, who had amended his own name at thirty-six, “for intrigue,” and enjoyed a high-paying client roster of gay men who needed healthy friendships and wives who desperately needed to know if their second husbands were really attending this many corporate retreats. (They really are, Adaem had told Liam. It’s quite absurd.) His services were highly rated, and as much as Liam liked to play off his divinatory powers, Adaem had once been featured on a popular morning show with a grieving widow who gasped at each vague, perfunctory message from the beyond, and though I once could only ever roll my eyes at his ordering from a cocktail menu, I found I now could not summon the slightest skepticism of any potential prophecy. Whatever had repulsively magnetized me from him had suddenly, unstoppably flipped, and now, I was pulled to him. I needed to know what he knew, urgently. I found myself awake late, watching clips online entitled “Walk into your soul’s mist.”

“Oh sweetie,” he said, regarding the space he’d seen before. “I’m just going to say it. You know it. I know it. You have terrible energy. What’s been in here? This place is full of rot.”

“I don’t agree with that?” I said, certain he was right. “Can you fix it?”

He gave me a look, slow, as if to say he was getting to that.

“I was getting to that. No.”

“I’m paying you fifteen hundred dollars.”

“I couldn’t do it for five times that. Can’t. Your heart is not pure. It is, however, as I am sure you know, a very reasonable rate.”

“My heart is ‘not pure’?”

“No.”

“How do you purify a heart?”

“Have you ever been in love, dear?”

“What?”

He put a hand on the counter, then lifted it quickly off, as if it were a metal hotter than he had expected.

“That was acting, the marble is nice; it’s really held up. Other people will wow you with theatrics, not me. Love, my dear!”

“Yes. I’ve been in love.”

He eyed me skeptically. “I don’t think that is true. Be careful what you call things, dear.”

“Then what?”

“Listen.”

“I’m listening.”

“What did I tell you just a moment ago?”

“You told me to listen.”

“I asked,” he said, barely concealing a deeper annoyance than he wanted known, “for you to be careful what you call things. Return in half an hour. I am starting in the bathroom. I will do what I can.” I opened the door to leave, and he added, “I really should charge you more for this, hun, but. He’s not coming back.”

“Excuse me?” I hesitated in the frame, shocked by his boldness. “Who are you to be giving me advice?”

“Ah, Liam filled you in. You know, it’s true. There’s such a thing as saying too much.” He paused for a moment, and ran the sink. Over the sound of rushing water, as I closed the door, he added, as if just to himself, “And, of course, knowing too much.”

—

The reorganization project was Adaem’s idea, or his prescription, to cement the bond I shared with this new space. He suggested, very briefly, that I place the old life behind me. Have I changed the lighting? My morning routine? Have I changed the shower curtains, the laundry basket, the meals I make at dusk? I’ve tried it, I had told him, but in fact I had not ever thought about abandoning those habits which were mine all along. There was no difference, or if there was, I was not aware of it, and I began to obsess over the way I had been unpacking boxes with Liam at twenty-six. The candles without their holders, the cheap bulbs busted in their box. The way I could recall in an instant the scene of that empty living room and shining wood hallway, the vine growing in through a crack in the brick, but could not remember his face then, or when I had last seen my mother, and what’s worse, very nearly did not care, as if the life I’d yanked us into had been her parting gift to me, penance for her absence, an inheritance I was owed.

I put the television on the other side of the room. I moved the desk drawer, placed the espresso machine and blender opposite their usual spots on the marble counter. I set the small fig tree with its wilting leaves in the kitchen and the steel trash can in the living room. When I was done, it looked as if I’d tossed the contents of my apartment randomly about the space.

Later, I realized the porcelain Madonna Liam had forgotten to take lay in its regular spot on the mantle. I laughed until it hurt to smile.

—

It was hard to make out Short’s voicemail. It sounded as if he was laughing through strangulation. When I rang him back, it was that same voice.

“Buddy,” he said, though we were in no way friends. “Buddy, too funny.”

“What’s going on?” I asked. A nervous break—I’d feared one myself.

“You know that video? Those marks.” He paused very deliberately to take a breath. “One of the interns fucked with the tape. Final Cut Pro. Can you believe. We’re all dying here.”

I heard boisterous laughter from the bar. “You can’t be serious.”

“Tell your boyfriend,” he said. “I tried to call him but he’s recording something for radio. NPR? He hung up before I got to it. Big shot. After that set we did not see that coming.”

I thanked Short and hung up. I imagined him replaying the tape, a joke behind our heads each time. I clicked open the DVD player I’d rarely used, removed an instructional cooking series Liam must have been watching, and replaced it with an intense at-home fitness plan someone had gifted me years ago during the peak of the fad. The console made a loud crunch as it processed the disc. A tan man with synthetically blue eyes appeared on the screen. “Heya,” he barked off the main menu, thrilled by his own energy. “I’m Rick. Today is the first day of the rest of your life.” He said this while striking his knees against downturned palms.

For the next forty-five minutes I pressed my body to the floor in increasingly straining positions at Rick’s command, lagging every so often behind what seemed more like backup dancers than athletes. Rick never broke a sweat, but at the end of my last set, I felt a hard cramp up my chest, a tightness just under my heart. The living room clock struck midnight. I lay on the floor, pleasantly sore. A gust of wind made a fast ghost of the curtains. I fell asleep there, with the same effort I had used to punish myself into another set of pushups. I made myself think, as I watched that porcelain figure, at least now it’s the second day of the rest of my life.

—

Later that night, I waited on my sofa with an old radio turned to the station, listening to eccentric, lonely people phone in with wrong answers to sports trivia, eager to hear Liam’s voice come through over the air. At last, he was introduced, and the sound of applause came through behind him, one of the audiences from a recent show. I wanted to know, insanely, if Liam would mention me, if an inflection might offer a tell. But he was different. He was solid, unwavering, and warm. He sounded as if all his years had been leading to this moment, and I was shocked to find that beyond all jealousy, all the ruthless memory I could drudge up from the rotting detritus of our past, I was proud of him for what he’d accomplished, and more than that, I believe he deserved all of it.

“The show is called Three Strikes,” the host said.

“Well,” Liam said. “I am out.”

“In all seriousness, it really is uncanny,” the interviewer said with genuine admiration. “Your knack for this vulnerability that just… explodes into something hilarious.”

“Expires even,” Liam said. I was relieved to feel Liam come across charming but, ultimately, basic. The host laughed, then thought aloud—“I’m trying to think of someone with your style for this, and I’m coming up empty. But of course, my colleague and I were reminded of Sedaris.”

“I’ve found,” Liam said with a thoughtfulness that verged on condescending, “that it’s about extending the set up past its obvious punchline, its easy resolution. The joke is always someplace you didn’t think at first. Usually, if you just keep going, it’ll come to you.”

I think we need to talk, I texted Liam. I found something.

I knew his thrill at the segment made him susceptible to engagement. He replied a moment later: I can come by around nine.

—

Liam arrived a half hour late, proving his ability to act like me. Cold, hard rain had begun to fall, knocking the roof. If it had been a few degrees cooler, it would have been snow, melting against the warm window. Instead, brown leaves shook violently with the wind, thunder growling across the dark sky.

He hung his raincoat and sat down across from me, the formality set, like an interview. I hoped something would loosen the knot in the air between us, but each of our movements seemed to tighten it like a noose. I stayed perfectly still. A branch cracked loudly outside.

“You got all your things?” I said.

“Oh, yeah. Or I could live without them. Thanks. That was a rainy day too,” Liam said. “But not like this.”

“It was.”

“I was so freaked out. The thunder made me jump into the bathtub.” Liam laughed.

“I slept with the lights on,” I said, pretending this no longer humiliated me. “You left stuff though. I read the joke book. I still have it if—”

He grimaced. “I read a lot. Used to at least. Something to learn in the mess, you know.”

“I like the thing about the Second Story. About building up to a punchline,” I said. “How you can give it a name like that. I didn’t know there’s terminology. Comedy’s a science too.”

“Yeah,” he said. “It’s storytelling. It’s really not easy.”

“Almost hard,” I said, with a recuperative edge of rudeness.

Liam smiled, very kindly. “Did you invite me here to insult me?”

“Incredibly, no,” I said. “In that book you wrote this joke, about my mom, and painters.”

“The ex comment, god,” he said, flush with genuine apology I couldn’t pretend was something else. “I’m sorry.”

“How did you know?”

“The same way you did,” he said.

This felt true but I rejected it. Whatever happened that night had been my mistake, though I wasn’t ever able to fully recover it. I felt nauseous from the idea he had wanted it too.

“I just keep thinking. That day, in home ec,” I started, frazzled and unraveling. “Like what even was that? You never even spoke before then. I had never noticed you.”

“I noticed you,” Liam said, a bit too sadly. He wet a cloth and began to wipe down the sinkhead, then the blender in its corner. “God, I can’t believe I remember it. It’s like, embarrassing.”

“Oh, come on,” I said.

“Well, I did.”

“Why did you say that stuff?” I asked. “It was like a whole different person. It was amazing but, I don’t know. I didn’t know you at all, and I wouldn’t have, if it weren’t for that day.”

“Honestly? I knew you’d like it.”

“What?”

“I wasn’t being funny,” Liam said, swiping the marble counter where he’d already polished it to a reflective shine. He turned to look at me. “That day? I know you don’t believe anything I say, but Mark. Honest to God, I was just being mean. Anyway, I need to go, but I had something to tell you. I’m moving. Sydney, next month. New job.”

“Wow,” I said. “Congrats. Kangaroos punch, by the way.”

He laughed sweetly. I believed everything he said. I wanted him to keep talking. The knot tightened one last time, and he shrugged on his raincoat and left me there with it, along with those drying bootprints I followed, later that night, pointless and imbecilic, to the foot of the elevator. He might as well have been across the ocean.

—

The part I have to underline is that I had intended to break up with him, in public, which I thought (I recognize the irony now) ran the least chance of having us make a scene. A few weeks before those marks at Comik, before terror streaked bright red onto the walls of our lives, I had met Liam after work at the bar next to his office, where suited men and their wives spoke over each other until the sound of a full plate dropping on the floor was rendered inaudible in the din. I had felt my desire to see him waning, inventing excuses and then dismissing them, cowardly, throughout the day. Breaking up with Liam would require, in the space, a degree of shouting that was sure to unnecessarily escalate whatever conflict was to follow, and the apathy into which I had settled became comfortable whenever I wasn’t actively considering it, like a splinter that had begun to live in skin.

After three cocktails, we stepped outside, the cold wind howling around us down to the Hudson. We walked, and he told me jokes that he hoped to try out at some open mic. They were offshoots of previous jokes he’d told at the few mics I’d attended, ones that made audience members loudly and uncomfortably “ha.” Liam confessed that he’d been placed on a performance improvement plan at work, was caught in a recent meeting smirking at something he’d written, which had then turned into something else. The casual way he disclosed these things, as if they were the setup to a joke, astonished me. He had worked for years to be at those meetings, to sit where he did at those tables, and now, he could not be bothered to care. There was an agreement here, unspoken if hard as the concrete we walked, that for as long as we were together (and it didn’t matter what I’d been about to do), we would incur the suffering and indignity and pain of the lives we’d chosen without discussion or even recognition.

The memory of alcohol stung me from the inside, lashing the back of my throat. We walked until we found ourselves in front of the Whitney, its bright lobby crowded for a newly returned Warhol installation. Liam and I maneuvered through the clusters of families inside, numb from the cold. The lights grew dim near a glow-in-the-dark installation, before our eyes adjusted to a loud pop of light. We moved from room to room, avoiding then re-seeing each other, when I heard Liam gasp. On a far wall behind red velvet rope, those three paintings. A small plaque on next to the blue: Original Lana Tristan (b. 1880). Work of the painter and murderess, who was rumored to have been buried alive. Discovered next to garbage, West Village, New York, 2019.

Bile-coated laughter rose in my throat. “OK, you have to admit,” I said to Liam, whose face had gone pale. “Now that’s kind of funny.”

—

Comik didn’t renew the lease, something I learned on my way to meet Clark, an overdressed friend of a friend visiting from Miami who owned a string of condo complexes and posted jokes about eviction on his social media. We were supposed to meet at a place a few blocks away from my stop; I took an accidental left out of the subway onto that wrong street. Of course I thought of the club often (cellar, I sometimes corrected on Liam’s behalf), but hadn’t expected to see it now. Its exterior looked usual but advertised a large sign in bright yellow script: Improv now! An acting school. One large room through the window, a streetlight reflecting off a long mirror, my silhouette standing dumb in the back of a laughless room.

Later than night, over a third cocktail, while Clark went on about a tenant’s cocker spaniel that had gleefully leapt into the community pool from a third floor balcony, I found myself thinking of that room with its oak floor, the groups of students learning to make each other laugh. All those years. I blinked and saw myself in front of that dark mirror, waiting—wanting?—for those marks to appear behind me, and finally mean something. I blinked again, and Clark asked me if I was okay. At his place, while he slept, I watched the ceiling change from yellow to black as the cars passed from headlights bright on the interstate. After a few hours, I got dressed and left, careful not to wake him, and rode a jostling subway home next to a discarded plastic bag that read I LOVE NY. I could see it caught between the doors, flapping wildly. I could feel Liam’s laugh inside me, or maybe it was my own.

—

Rick with the fake blue eyes was right; the next day it really was the rest of my life. I started visiting my mom in her cemetery, driving up the interstate late, listening to weather reports, adjusting the dial whenever the host attempted a joke. I brought her pink and yellow tulips in spring, wreaths that collected snow like sugar as it fell late one January, headlights veering out behind me, breaking the view as the headstones cut one after another with their long shadows for me to be with her, alone. I spent time looking up Liam on the internet—the little photos I could see on his profile of him with a short, wide-mouthed man named Tom whose integrity felt evident in his selection of polos and lack of online footprint. Photos of koalas and sunsets, so many memories. Then suddenly, one day, as if it were just the next, the marriage, Liam’s hand, which I was chilled to find I could recognize, on a shining silver blade making its clean cut into a large white cake. And the flowers on Valentine’s Day, all the kindnesses I withheld from him, or offered at a belated time, proof he had never been enough for me to remember, cursing me now that I could not forget him.

And that was around the time I met you, yellow crocuses and melting snow in Central Park, catching each other on the wide lawn. Coffee followed by drinks, a lifting feeling that made me aware of my body. Like thawing out, madly. I waited months for you to return, to meet you at this hotel, to be in this bed. And even though I know you’re leaving for Boston tomorrow, and to Chicago with your wife after that, I wanted to try to tell you, in this hotel room, maybe just to practice it in front of a mirror, this first story of how we never know what’s really true, or maybe just get to decide what is by living with it, or through it. And even though maybe it’s something people just say—When did you know you were in love?—you were the one who asked, and for once I want to answer. For once I know.

When you went to the bathroom for a towel, I watched the hairs on my forearm stand up in the sudden cold, the churning air conditioner compensating for that crazy heat outside making gray mirages of the street, joyful screams around a broken fire hydrant gushing water, neon lights from Times Square turning the curtains blue, then orange, then a bright, holy red. My second story—well, I guess it was easy to see now, impossible as it was to explain. It was the story of me—the man who fell in love and out of it, the whole time without a clue of what love really was, not the faintest idea he was living it. And feeling the real force of that love hit him in the gut, like a fit of uncontrollable laughter right now, out of nowhere from across the sea, all these years later. And the funny part is that even though in a moment you’ll be right next to me, and even though you asked, I won’t be able to tell you. From now on it will always be the one story, and then it’s three: you and me, and the him behind the mic—a ghost just out of my vision, shapeless marks I can’t quite see.

Hurricane Season is a noir thriller about fighting and addiction, prison and drugs; but more than that, it is a love story set in the carnage of an America wrecked by inequality.

Hurricane Season is a noir thriller about fighting and addiction, prison and drugs; but more than that, it is a love story set in the carnage of an America wrecked by inequality. Mark Powell is the author of seven novels, including Lioness, Small Treasons–a SIBA Okra Pick, and a Southern Living Best Book of the Year–and Hurricane Season. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Breadloaf and Sewanee Writers’ Conferences, and twice from the Fulbright Foundation to Slovakia and Romania. In 2009, he received the Chaffin Award for contributions to Appalachian literature. He has written about Southern culture and music for the Oxford American, the war in Ukraine for The Daily Beast, and his dog for Garden & Gun. He holds degrees from the Citadel, the University of South Carolina, and Yale Divinity School, and directs the creative writing program at Appalachian State University.

Mark Powell is the author of seven novels, including Lioness, Small Treasons–a SIBA Okra Pick, and a Southern Living Best Book of the Year–and Hurricane Season. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Breadloaf and Sewanee Writers’ Conferences, and twice from the Fulbright Foundation to Slovakia and Romania. In 2009, he received the Chaffin Award for contributions to Appalachian literature. He has written about Southern culture and music for the Oxford American, the war in Ukraine for The Daily Beast, and his dog for Garden & Gun. He holds degrees from the Citadel, the University of South Carolina, and Yale Divinity School, and directs the creative writing program at Appalachian State University.