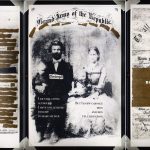

In the spring of 1982, at the end of my senior year in high school, I was admitted to a mental hospital in Hartford, Connecticut, named the Institute of Living and was institutionalized there for two years. The Institute was founded in 1823, the first private mental hospital in the country. It was named the Hartford Retreat for the Insane and sat on thirty-acres on a hilltop above the Connecticut River. The first medical director was a brilliant young doctor, recently graduated from Yale, named Eli Todd. Whereas before, the mentally ill had been viewed as possessed, had been shackled, warehoused, or worse, Todd had a revolutionary vision for the humane treatment of the mentally ill: what he termed “moral treatment.” In Todd’s view, the mentally ill were citizens deserving of care and treatment and, ultimately, capable of rehabilitation and recovery. The key tenets of his treatment were “pleasant and peaceful surroundings, healthy diet, kindness, an established regimen, activities and entertainment, and appropriate medical attention.” “The great design of moral management,” Dr. Todd once said, “is to bring those faculties which yet remain sound to bear upon those which are diseased.”

I grew up in Hartford, often passing the Institute on Retreat Avenue in our wood-paneled station wagon. Driving by its imposing six-foot-high brick walls, my mother would comment, “There’s the country club.” And looking at those walls that surrounded the entire campus on all sides, I could imagine that it was a sort of English Tudor, turreted type of place. “There’s the country club,” I would echo.

I had broken down at school after I received an offer of admission from Yale University, scratching the inside of my arms with a razor blade as tears bled down my cheeks. I didn’t deserve Yale, I thought. I could never make it there. In fact, I could never make it anywhere. I had been a student at a small boarding school for girls in northern Connecticut. I had friends there, and teachers who encouraged me in an environment that felt like love itself. My school home was the opposite of the home in which I had grown up, in which I was despised as a disgrace, a lumbering, teeming, obese, and greasy monstrosity, a source of shame and disgust for my attractive parents. The love I had felt at school was all illusory, I realized that day in April, the thick envelope from Yale in my hands. I was not deserving of the kindness and care I had received during my years at the school. I could never make it at Yale. I could never make it anywhere. The fact that I had been admitted when my beautiful friends had not was an outrage, a cosmic wrong that could only be made right by taking a razor blade to my arm. When the cuts were discovered, the school psychiatrist recommended admission to the Institute. The recommendation came as a relief. A mental hospital would be a far more appropriate place for me, I secretly believed, than the hallowed halls of Yale.

And this mental hospital had a reputation that was equally hallowed, a cross between a country club and a vaguely dangerous sanitarium. I was taken on tour of the grounds a few days before my admission, the first time I had been inside the six-foot brick walls. It was a sunny, beautiful day in May and the campus was almost gleaming. The green sloping lawns, an aqua swimming pool (unused), and the largest flowering dogwood tree in Connecticut lent the impression of a hospital more spa-like than Bedlam.

I, of course, had read The Bell Jar, and I could easily imagine Sylvia Plath’s fashionable, intelligent and humane Dr. Nolan here, wearing “a white blouse and full skirt gathered at the waist with a wide leather belt, and stylish, crescent-shaped spectacles.” I had a brief consultation with a psychiatrist at the Institute’s Children’s Clinic. He wore a corduroy jacket with suede patches at the elbow. He puffed on his pipe as I sat in his cluttered office and tried to describe why I had cut my arm.

“I think it would be best for you to come to the Institute for the summer,” he told me, “so you can be all fixed up and strong for Yale in the fall.”

It seemed a reasonable, even hopeful plan. The prospect of Yale loomed like a leviathan in my mind; a place full of students as disciplined and serious as my father, frugal and ascetic and fiercely intelligent. I on the other hand was gluttonous and hedonistic, a disgrace—too loud, too voluptuous, too greedy, too fat, too emotional, too funny. I had thick eyebrows and fat lips and a tiny, ridiculous voice. I ate and ate and ate and ate. I would be much more appropriate in a place populated by the people of Robert Lowell’s poem about McLean Hospital, “Waking In the Blue.” I didn’t understand the poem then, not really, but it was so extraordinarily lush and generous and almost loving about all those Mayflower screwball patients like Bobby, “redolent and roly-poly as a sperm whale in his birthday suit.” I wanted (naively and stupidly) to be in Lowell’s place, where azure day broke, where I could feel safe, where that overwhelming pressure to hurt and punish myself could be lifted, maybe, just an inch, like in Plath’s The Bell Jar, and the fresh air could come rushing in.

What I didn’t know then was that the Institute, in its ambitious expansion, had become a far larger and more menacing institution, a hospital of last resort for patients who had failed or been expelled from other treatment facilities. It routinely performed a rudimentary form of electric shock therapy and bound patients in ice-cold sheets called wet packs for hours at a time when they acted up. There was an entire five-story “research” building constructed for the purpose of performing icepick lobotomies on patients from all over Connecticut, as such cruel and brutal operations were illegal in nearby Hartford Hospital. The advent, in the 1950s, of anti-psychotic drugs—like Thorazine—enabled the hospital to control unruly and disturbed patients with chemical restraint using doses of these powerful drugs that far exceeded the therapeutic range. Moreover, and most importantly, the insurance policies of the day, in the city known as the insurance capital of the world, often covered months and years of hospitalization, so an extended stay at the Institute was no longer the purview of the very wealthy.

By the early 1980s, when I was admitted, the hospital was taking full advantage of an adolescent population whose parents had good insurance. At the time I was admitted, the Institute had more than four hundred inpatients, nearly all of them hospitalized for long-term care (often called custodial institutionalization), and nearly always paid for by insurance policies. This was also the case with me. When I was admitted, I was covered under my father’s policy, which provided full coverage up to $1.5 million dollars—the equivalent of thirteen and a half years at the Institute. And I was stepping into an Institution whose financially savvy (or cynical) directors were more than ready to take advantage of an insurance policy that covered everything for a long-term stay and a family that wanted their troubled adolescent off their hands, and even out of their lives.

The Monday following my consultation, my parents and I drove through the black wrought iron gates for our admission appointment. An aide helped my father with my suitcase and then took it away. We sat across from each other on upholstered chairs in the mustard-colored lobby, my parents silent, holding hands. My mother was wearing a beige suit with gold buttons and sling-back spectator pumps. There was an air of excitement, almost giddiness about her, her hair glistening and her legs crossed prettily at the ankles. She had shopped carefully for her new outfit, spending Saturday at Lord & Taylor’s while my father and I watched old episodes of Hill Street Blues my mother had recorded on VHS tapes. My dad had been silent waiting for my mother to return, sitting next to me in front of the television, his pipe in his mouth, watching one tape episode until its end, and then replacing it with the next, in our old machine that ground and clicked.

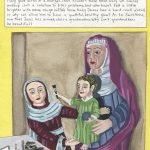

My parents were instantly infatuated with my doctor, a tall, lovely Norwegian psychiatrist named Erna Mugnaini. She had blue eyes, wavy blond hair, and a daughter my age who was going to Smith. She spoke with a mesmerizing Nordic cadence that seemed intrinsically kind. My father dubbed her, “The Good Doctor.” She would speak to my parents first, she told us, while I got settled in the unit. Later that day she would come and talk to me.

I have the record Dr. Mugnaini wrote of her first meeting with my parents. It is telling that her first impression of me came from my parents, rather than from me or from any of my teachers. I had been in boarding school for four years and saw my parents only on breaks. I had not lived with my father, at all, for more than six years, not since I was twelve years old. She did not hear from any of my teachers, or my friends, or my house-parents, or any of the people I had been living with for the past four years. My parents, whom I seldom spoke to or saw, became instant authorities on my condition and adjunct therapists.

In the intake summary, Dr. Mugnaini writes: “Dolly’s emotional difficulties date back to childhood. According to both parents, she has always been a moody, demanding, oppositional and jealous child.” She describes my father: “Mr. Reynolds is an attractive, slim, healthy-looking man in his middle forties. He is friendly and polite but does not reveal many emotions and was rather factual in his account about the daughter.” About my mother, she writes, “Mrs. Reynolds is an attractive, slim, forty-year-old[note]Actually, on that day, she was forty-one. I don’t know whether this is a small typo by Dr. Mugnaini, or, more likely, a small vanity on the part of my mother.[/note] woman, looking younger than her age, well-dressed, pleasant and cooperative.” My younger sister, Kitty, was described by my parents as, “outgoing, friendly, easy to get along with, a bright girl but not particularly interested in schoolwork.” She goes on, “Kitty was born when Dolly was almost two years old. Mrs. Reynolds believes she ‘catered’ to Dolly to prevent her from feeling jealous, as both parents describe Dolly as moody and attention-seeking since early age.” Clearly there was only one problem in this family, soon to be behind locked doors.

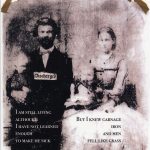

Later, when my parents came to say goodbye to me on the unit, my mother told me excitedly that they had all come up with a name for all my problems: “no brakes.” I had never been able to stop myself; I had insatiable appetites for food and love and attention and jealousy and rage and despair and hopelessness. “No brakes,” they would repeat throughout my life, when they described the enormity of my appetites and emotions. But “no brakes” is what happened to the Institute, my doctors, and my parents as I rapidly descended into the world of an institutionalized patient and my father’s insurance company mailed the Institute reimbursement checks for my care, regularly, on the first of every month.

Dr. Mugnaini placed me on an intermediate unit, meaning the doors were locked but most patients were allowed on the hospital grounds in scheduled, supervised visits. The aide, Patty, who escorted me from the reception area, had a set of keys clanging from a chain she wore around her waist like a belt. Patty was tall and soft-spoken, knock-kneed in her white Levi corduroys, a kind and patient young woman who wore tinted glasses and treated us patients with compassion and gentleness. I could sense this on that first day, and I was not afraid, even as I saw that the entrance to my unit was a double door with a small pane of prison glass at eye level. Patty unlocked each door with a series of clicks, and then barked at Debby, a patient who was peering out as we were peering in. The name of my unit was “Todd,” for the great and humane Dr. Todd, the Institute’s founder.

The unit itself was quite dingy—walls covered with chipped mustard paint, mismatched, sagging couches, a brown carpet badly stained. It was hot and muggy, and all the windows were closed. In the center of the long hall was the nurses’ station, walled off from the patients by a double layer of thick Plexiglas, with a small opening at waist-level through which the staff passed medication at four scheduled intervals each day. Next to this Plexiglas window the cigarette lighter was mounted on the wall, a small burner with an on-button the patients could press and then light their cigarettes off the hot orange circle, a mental patient’s kiss. Patty, whom I would come to know over the next two years, was one of the most humane and accepting aides in the entire hospital. It was fitting I met her first, when I was still a person on the outside. Stepping through those Todd doors with her was like stepping slowly into the pool, step after step, as the freezing water moves up your body little by little, until you are submerged.

Nancy, another aide, showed me into my room across from the nurses’ station. Nancy was what I would have then called prissy, her hair permed into perfect waves around her face, her lips pursed in vague disapproval or disgust. She blinked constantly—a tic. She had me remove my clothes and stand naked while she emptied my suitcase and searched through every crevasse. She took my driver’s license and cash and returned my empty wallet. After snapping on two layers of latex gloves, she had me bend over so she could pry open the lips of my most private parts, to search inside.

After I had gotten dressed, she handed me a small plastic cup containing three pills, two small tablets and a bright red capsule. After I had swallowed the pills, she had me open my mouth again and probed my cheeks and under my tongue with a wooden tongue depressor. Satisfied, she left me alone.

I found out later that the three pills were: 1) an antidepressant called Asendin (an older tri/tetracyclic no longer prescribed. Also, what a name!), 2) a catastrophically potent anti-psychotic in the same class as Thorazine called Trilafon, and 3) a drug called Symmetrel which is now used to treat Parkinsonian movement disorders. It was prescribed at the Institute because the older anti-psychotics like Trilafon have a terrible side effect: dyskinesia, which causes uncontrollable muscle movements, twitches and rigidity.

Most of the patients at the Institute looked like they had Parkinson’s. Those terrible drugs—Thorazine, Stelazine, Mellaril, Navane, Haldol, and Trilafon—were liberally and universally prescribed, in very high doses, and not only to patients with schizophrenia, but also to nearly all adolescents in the locked units, especially if they were unruly or acting out, which was also fairly universal. The discovery of these drugs in 1950s is considered a revolution in psychiatric care, allowing schizophrenic and other psychotic patients the possibility of an actual life. The way those drugs were prescribed at the Institute had the exact opposite effect.

Of course, I didn’t know any of this when Nancy handed me that first cup of pills, offered on a tray so that our hands would not touch. I had never heard of any of these medications. I had no idea that depressed people would be treated with medication instead of what I had imagined: kindness, insight, rest, and poetry workshops led by Robert Lowell and Anne Sexton, as had happened McLean’s and the other asylums I had read about.

I also didn’t know what my own initial diagnosis was, and didn’t learn of it until years later, when I read Dr. Mugnaini’s intake summary and discovered the catastrophic sentence: atypical mixed personality disorder with borderline, narcissistic, and histrionic traits. This very rococo description was, I’m sure, a result of Dr. Mugnaini’s conversation and collaboration with my parents and meant there was little hope for me in the world. My prognosis: “very guarded.”

Over the course of the my first few days and weeks in Todd, the medications were increased incrementally. I was lining up at the nurses’ station to swallow pills four times a day, until I was taking the maximum dose of the anti-psychotic drug Trilafon. With each swallowed dose, I lost progressively more control over my consciousness and my body. It was so sedating at first that I began to count the minutes to the next time I could sleep. I would get into bed one second after swallowing my 9:00 p.m. meds and fall into a black hole until Nancy woke me the next morning, rapping loudly on the wall above my head with a flashlight, her clipboard in hand.

I got to know some of the other patients. They were all women, and young, from age fourteen to about thirty. They introduced themselves with their diagnosis, the self and its affliction inseparable. Many of these women suffered terribly. There was Brenda, a lovely dark-haired woman a few years older than me, with violent manic-depression, cycling disastrously from psychotic mania to catatonic depression.

“My doctor can’t regulate my meds,” Brenda said to me, her hands shaking, a light sheen of perspiration across her forehead. Her doctor was Mavis Donnelly, the scion of one of the Institute’s previous luminaries, John Donnelly, a chief psychiatrist with a building erected in his name during the expansion in the 1950s and 1960s. Dr. Mavis Donnelly was young herself, a few years older than her patients, brutal and profane. One terrible day Brenda was out of control, wild with mania, and the nurses called Dr. Donnelly to the unit. When the doctor arrived, striding in in her tall black boots and wrap-around skirt, Brenda was jumping on and off the side tables next to the sagging couches in the dayroom, flapping her trembling arms unevenly like mismatched wings and laughing hysterically. When she saw her doctor, she cried out, “Dr. Donnelly! Dr. Donnelly! I can fly! I am flying right now! Look at me! Look at me!”

I was scared; scared for Brenda, scared she would hurt herself, scared for how wild her mind had become. I looked to Dr. Donnelly to help, but what she did instead was point her finger angrily at Brenda and scold her as loudly as she could. “Get down!” she yelled, her voice a guttural growl. “Get down RIGHT NOW!” I saw her snap her fingers at the nurses, and suddenly the aides were pushing us all into our rooms.

“What’s happening?” I asked my roommate.

“Brenda’s getting Gooned,” she answered.

And then I heard it, the thunder. When the staff hit the “Goon” alarm, five or six burly male aides came charging onto the unit and tackled the unruly (or offensive to staff) patient onto the ground. My roommate cracked open our door, and I watched as the Goon squad held a screaming Brenda face down on the unit’s filthy carpet and bound her wrists and ankles with leather straps. One of the Goons knelt with his fat knee in the small of Brenda’s back while she pleaded, “Please sir, please sir,” trying to catch her breath. Another Goon lay down a long black canvas bag with handle-straps next to her body. He pulled open a zipper that ran the entire length of the bag.

“What’s that?” I whispered.

“Body bag,” my roommate answered. “Like, for dead people. They’re taking her to Thompson.”

Thompson, the lowest of all the units, actually underground, in the basement, next to the steam room. Thompson contained the seclusion and restraint rooms, each bare except for a vinyl bed, like an exam table, in the center of the room, cemented to the floor. There were straps at each of the four corners, where patients were tied into “two-point” (wrists only) or “four-point” (wrists and ankles) restraints. The seclusion rooms were also where hysterical patients were “wet-packed,” a brutal and archaic form of “hydrotherapy,” abolished in nearly all modern hospitals[note]None of the psychiatrists I have seen in California, over more than twenty years, has ever even heard of wet packs, and had no idea that such practices were ever used on mental patients.[/note] but still raging away at the Institute. In wet packs, patients were bound, naked, between freezing sheets that had been soaked in ice water. The patients were left between these icy sheets and tied down for hours or even days. These descriptions now sound so baroque, unbelievable, even laughable, like some dark dungeon feature of a Gothic novel. But this barbarism was very much real and alive in Todd with a terrifyingly ill young woman and her angry doctor who could not tolerate seeming not in control of her patient. I watched as the Goons zipped a bound Brenda into the bag, lifted the bag with its handles, and carried it through the unit’s double doors, single file, like pallbearers. I also saw that Dr. Donnelly had been watching it all, her face frozen, impassive, her arms crossed tightly across her chest. It seemed incredible that ten minutes ago I had been happy to see her on the unit, thinking that she had come to help.

Where were the brakes then?

Brenda did not come back that night. I didn’t see her for another month, until I had been moved to Thompson myself. Brenda lay face down on her cot, immovable, nearly catatonic, as menstrual blood ran down her naked legs and soaked the sheet she was lying on. The Thompson aides screamed at her to stand up and clean herself up. Brenda was gone, unresponsive, unmoving, almost unconscious but still alive, her private blood sticky and red, a rebuke for all the world to see. But I was still in Todd when the Goons packed Brenda into the body bag. It was still early days for me at the Institute. I didn’t know any of what was yet to come as the unit doors in Todd slammed shut and the Goons disappeared. Dr. Donnelly walked into the Nurses station to write her report. That night I swallowed my meds and let the blackness fall.

—

The incident with Brenda had left me badly shaken, and there were other things that scared me as well. I asked Dr. Mugnaini about the side effects of my medication. My vision had become so blurry that I couldn’t seem to read. It felt like my eyeballs were quivering back and forth in their sockets. I had been a voracious reader, but now that I had lost the capacity to see the words I had lost a part of the world that had defined me. My teachers at boarding school had given me books to read outside of class, Chekhov and Ann Beattie and Toni Morrison and Eugene O’Neill, and then had talked to me about what I read as they drove me back to the dorm on a Saturday night after I had babysat for their children. My English teacher would even ask me what I was reading and what I would recommend. My father, when he came to visit me at the Institute on Sundays, would bring the Sunday New York Times for me to read, the Book Review thoughtfully pulled out and placed on top. It is hard to think of this now, my sense of my father and his gift of a life of the mind. I didn’t tell him I couldn’t read; I was ashamed. I carried the paper around the unit on Sunday nights, opening the pages and folding them back, holding them in front of my face and refolding them from time to time, a mechanical image of the person I had been just a few weeks before.

There were other things happening to me in what felt like from the inside out. My muscles felt rigid, my fingers splayed out and my hands held out in front of my waist, like a Tyrannosaurus rex. I shuffled and sweated and felt anxious all the time, like the area inside my body wall was quivering, being tickled unbearably by some internal torturer. These feelings were probably a result of my anxiety, Dr. Mugnaini told me, pen in hand, bending her blonde head to write the orders increasing my meds.

“You can have an extra Trilafon as a PRN,” she told me.

“A PRN?” I asked.

“A little extra medication you can take to help you when you feel upset,” she answered. I was already on 40 milligrams of Trilafon a day, but I had the capacity to take 8 additional milligrams, which would bring me to 48 milligrams, near the daily maximum and a very, very high dose of powerful elephantine drug. The Trilafon had knocked my brain with the force of a two-by-four. I did not have thoughts anymore, not in the way I had at school, and the thoughts I did have seemed to take forever to cross from one side of my brain to the other. It was becoming harder and harder to speak, both the act of moving my increasingly slack lips and the mental capacity to find something to say.

“You are quite ill,” Dr. Mugnaini told me. “You will need the support of the hospital for quite some time.”

And there were also other, more intimate shames that I was also keeping from Dr. Mugnaini. When I stood under the warm water in the shower at night, something was coming out of my breasts: a thick, milky yellowish fluid I thought was pus. It seeped and even squirted from my nipples, staining my towel, my nightgown and my bra with this unspeakable fluid.[note]Later I would find out that this was a bizarre side effect of the Trilafon called “galactorrhea.”[/note] And even worse, it was becoming harder and harder for me to urinate. It seemed to take longer and longer for my bladder to unclench. It was like I no longer knew how to send the signal for the muscle to relax. I had always, always been ashamed of my too chubby body, from the time I was in kindergarten and was not allowed to wear pants because people would see how fat my legs were. I had large breasts and thick lips and fat fingers; I believed that everything about me was grotesque and the filth on the inside of me was now seeping out as well. What kind of animal doesn’t know how to urinate? I was too ashamed to tell anyone what was happening.

By this point I was barely speaking at all. I had lost the capacity to read, I could barely think, I drooled when I opened my mouth, and unspeakable things were happening to my body from the inside out. I was eating almost nothing. It was the end of the world. I asked Dr. Mugnaini repeatedly if this could be from the medication. She looked at me thoughtfully and shook her head.

All brakes were gone.

—

All these years later, all these miles away, I think about what had happened to me as an eighteen-year-old, how I became an institutionalized, backward patient, sitting on the filthy floor of the basement unit Thompson, shaking and drooling and praying to God for each moment to pass, for two endless years, until the insurance company cancelled my policy and I was released, blinking, into the sun. I think about how the good Dr. Mugnaini kept increasing my Trilafon as I increasingly devolved, mistaking the side effects of the medication as symptoms of my ever-worsening pathology. I think about how this was all allowed to happen in an institution founded on the most humane and revolutionary treatment of the mentally ill, and how this institution lost the brakes on its greed, happily depositing the reimbursement checks from my father’s insurance policy as my life seeped slowly away. But most of all, I worry that I have lost the brakes on my own memories, that I can slip from being a mother and writer three thousand miles and three decades away from this experience, right back to the drooling and tortured mental patient I had become, and, in my most secret places, am still. And what I cannot seem to fight is the sense that my slim and attractive parents, mother in her spectator pumps, my father with a legal pad on his lap, the good doctor listening attentively, had been right all along. There are no brakes for that.

———————————