Graphic Rage, by Aubrey Hirsch

Graphic Rage, by Aubrey Hirsch

Split/Lip Press; $24.00; softcover

October 7, 2025

Review by: Nathan Holic

In 2017, we had the great privilege here at The Florida Review to publish “The Language of Trauma,” a graphic essay from an author named Aubrey Hirsch. Hirsch had already published widely by 2017, but she was (from what I understood) only beginning to dabble in the comics form. As the Graphic Narrative/ Comics Editor since the George W. Bush administration (my crow’s feet just deepened, typing that), I’ve always loved when poets and prose writers who’ve previously worked only in alphabetic text try their hand at sequential art. When such writers create something new and bold, it brings me a profound joy to publish this work side-by-side with established comics artists.

Hirsch is a fantastic traditional-text essayist, and she immediately made the leap to becoming a fantastic comics essayist. The transition was so adept as to feel preordained—from the first panel, you could see she was meant for this. Rereading the piece today—and I hope you will, here—remains an arresting experience, and I’ve found ways to assign the essay in several of the courses I teach at the University of Central Florida, from first-year writing courses, to courses focused on personal essays, to courses in comics and the emerging field of graphic medicine.

So, it’s tough to feign anything like objectivity as I begin this review of Aubrey Hirsch’s first collection of comics essays, Graphic Rage: Comics on Gender, Justice, and Life as a Woman in America. I’ve been reading her text-image work since 2017, and you could say I’m a fan. Can a fan even write a review? The invitation to read and review an advanced copy of the text felt less like a chore than a reward, a chance to follow in one manuscript the progress and career of an essayist and comics artist who is emerging as one of the finest practitioners of the graphic essay form, consistently producing timely text-image pieces that respond to the political traumas of the 2020s with humanity, reason, and (yes) understandable anger. Most impressive: collected here, these essays do not feel as if their thematic and emotional weight will diminish as newsworthy events fade from the spotlight. It’s a timely collection, given our current moment, but I’ve got to imagine that the book will be readable and impactful for years to come.

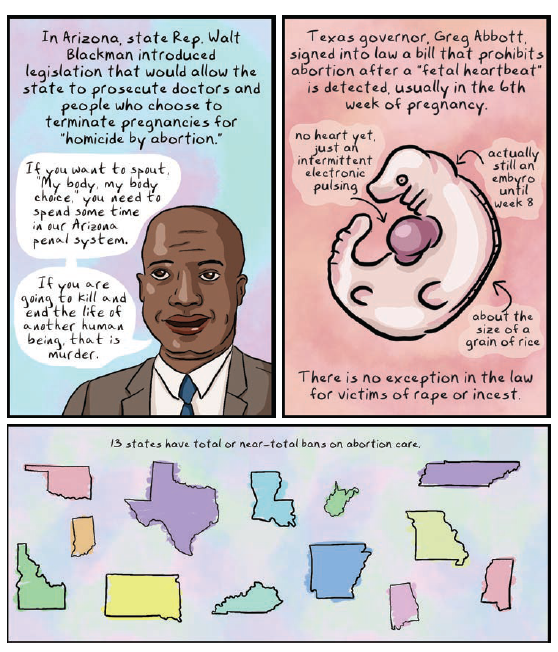

Releasing in October 2025, and published by Split/Lip Press, Graphic Rage is a collection of what various readers, critics, and creators might alternately term “graphic essays” and “comics essays,” short commentaries and op-ed style arguments on timely issues, communicated in some combination of text and sequential image, generally employing the grammar of the comics page—panels, word balloons, emanata, sound effects.

Visually, Hirsch generally lays out her pages in four (mostly) equal panels, a reminder that many of these comics were originally published in online spaces that favor this sort of uniformity; you can picture yourself swiping through these comics on Instagram, perhaps, one panel at a time, easily able to read the entirety of the text without pinching and zooming:

While this is the general structure of most pieces, some of the essays forgo traditional panel borders and four-panel layouts to assume either a looser, “journey of thought” quality where the text flows down the page into an image without panel borders—

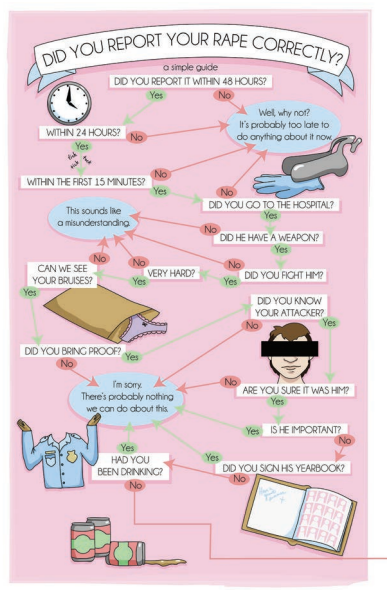

—while other pieces adopt different forms and genres entirely, as in this flowchart-based piece:

But for the most part, the visual layout is important to Hirsch’s purpose. Unlike graphic novels created for print distribution, these are urgent pieces that she has created for immediate online dissemination, and the function dictates the form. Only now are we finally seeing them in print.

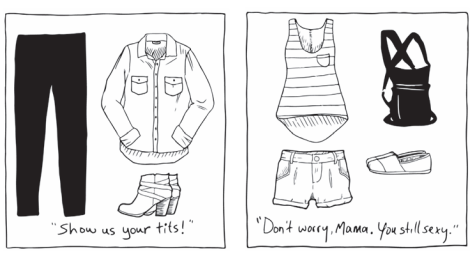

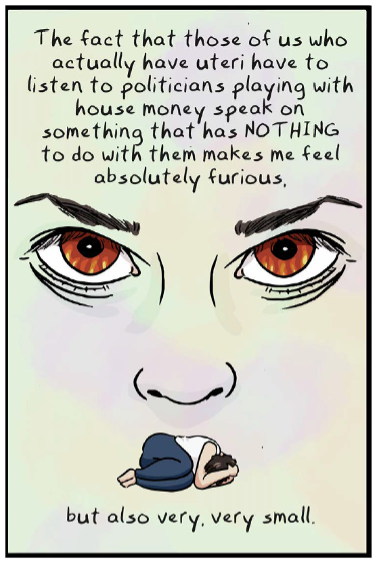

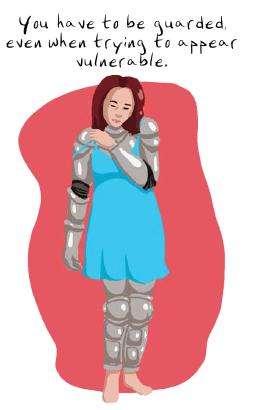

This uniformity of layout is not a criticism. Yes, the artwork is often iconic rather than photo-realistic (or—on the other end of the spectrum—abstract or stylized), the most distilled version of the image imaginable. No, there are no painstakingly detailed splash pages of the sort that we find in mainstream Marvel or Image comics. But I couldn’t have imagined these essays drawn in any other style. The visuals are restrained, patient, and always crafted in service of the message. When I’m looking for excellent comics, I ask myself one question: Has the artist chosen the right visual style for the message? Take, for instance, the black and white panels of “What I Was Wearing,” a sequence in which Hirsch illustrates her everyday outfits, coupled with the catcalls and sexual harassing threats that accompanied said outfits. There is a plainness to the artwork, but that horrifying plainness serves the essays.

I’ve read too many comics that beg obnoxiously to be taken seriously, artwork over-stylized to the point where it looks like a CGI sequence in a Hollywood blockbuster, panels crowded with text as if the only way to be literary or important is to stuff the page with words. It’s all very “look at me!” And it doesn’t demonstrate a synergy between text and image: the right choice image, the right style of artwork, the right amount of text to pair with the image so that they can both do their own separate (but cooperative) work.

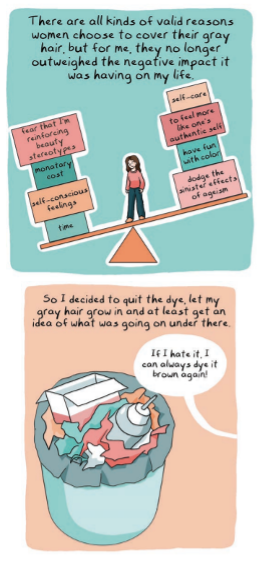

In Graphic Rage, Hirsch has created short pieces that are individually consumed in five to ten minutes, and easily shared, yet they resonate long after the read. Too much text, and we might tune out, or we might wonder: Why isn’t this just a traditional essay? But throughout this book, I marveled at how much these comics could communicate in a single page, or even a panel. Take a look at the following panel from “Going Gray,” and imagine how many words this might take to convey in a traditional essay:

Hirsch takes us through a full internal monologue in that first panel, as she weighs the reasons for allowing her hair to go gray. Another essayist might have spent several pages on this internal debate! She deftly braids personal narrative, charts, diagrams, and outside research, sometimes in a single page, and even visualizes the researchers she cites, allowing us to connect with researchers as humans rather than faceless names:

But it’s not just the efficiency of the text and image. Hirsch consistently creates striking visual metaphors that reinforce her ideas, or that offer new ways of seeing those ideas. The balance beam (above) is an easy example, but we see these visual metaphors on nearly every page of the book. Here’s another (and this might someday become the most reproduced image in the book):

These visual metaphors build upon the literal text, extending meaning, and (this is crucial for a comics nerd and comics teacher) illustrating the possibilities of the comics essay form. Why choose to write a comics essay when we could write traditional-text essays? See above!

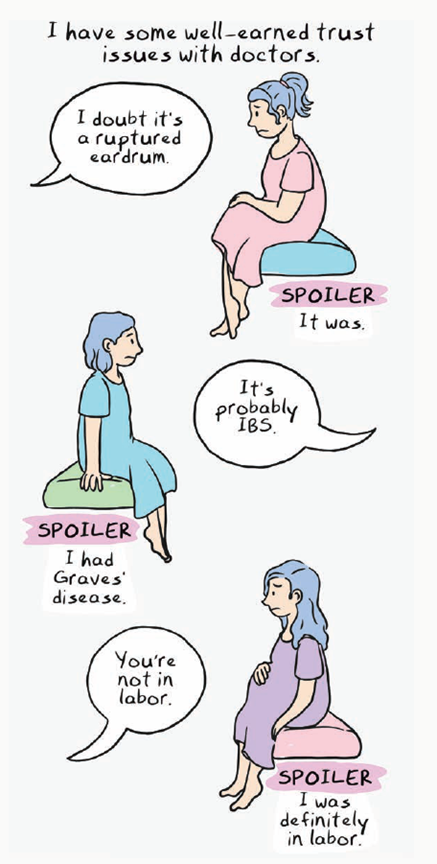

In this book, individual panels tell a full story. Individual pages beg to be shared, or (call me old school) clipped and tacked to your bulletin board like we used to do with Far Side cartoons. As readers, we might initially perceive some of the artwork as “simple” because it is not highly detailed, but we are frequently fooled into processing and remembering far more than we thought:

What an amazing image. What an amazing visualization.

What’s left to say about Graphic Rage? Have I geeked out enough about the visuals? Let’s talk content, then.

The subject matter of these essays can be gleaned from the book’s subheading, “Comics on Gender, Justice, and Life as a Woman in America,” and most of the essay titles preview an essay’s subject and Hirsch’s attendant gallows humor. See “Women Are People, Believe it or Not” and “How to be a Woman on the Internet,” for instance. Even “How to Correctly Report Your Rape” adopts a question (“Did you report your rape correctly?”) and a flowchart that leads the reader to the same inevitable, doomed answers. The collection is not ha-ha funny; when we laugh, it is from the same release as when we flip the bird or block someone from our social media account.

Hirsch’s voice has certainly been sharpened from years of steady publication in online journals and sites (Salon, Vox, etc), and the accompanying online toxicity that has been heaped upon her for her perspectives. (Several of the essays directly address these online threats.) Her work will no doubt appeal to readers of Roxane Gay, who is listed in the acknowledgements and blurbed the book. I feel compelled to make this comparison for a very specific reason: If you do not consider yourself to be a reader of comics, don’t be put off by the idea of a collection of comics essays. This book will make you a believer.

In fact, reading Graphic Rage, I felt much the same as when I finished Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist (2014). Here was an author whose work I’d been reading and enjoying online for years, and who—finally, you could sense it—was about to break through with her first major essay collection, about to dramatically expand her audience. She had been unleashed, the wider world was about to get a good kick in the teeth, and a whole lot of people would have a trusted voice that they could count upon. What a feeling that was. Aubrey Hirsch’s Graphic Rage gives me the same feeling. It’s a kick in the teeth, and I’ve got to imagine that her audience will only grow from here.

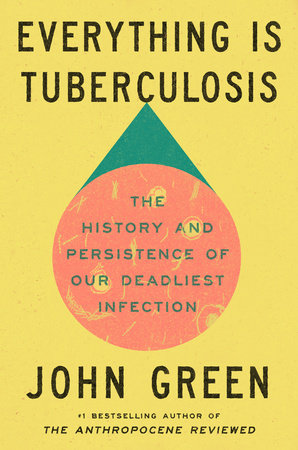

Review of: Everything Is Tuberculosis, by John Green; Crash Course Books; $28.00; 208 pages; March 18, 2025

Review of: Everything Is Tuberculosis, by John Green; Crash Course Books; $28.00; 208 pages; March 18, 2025

Despite the limitless expanse of the mind, the body is a woefully constrained vessel. In Garth Greenwell’s new novel, Small Rain, a mysterious illness seizes, reduces, and ultimately enlightens a poet. While the medical dilemma of the protagonist is harrowing, his rich, compassionate interiority provides succor. “I became a thing without words in those hours, a creature evacuated of soul.”

Despite the limitless expanse of the mind, the body is a woefully constrained vessel. In Garth Greenwell’s new novel, Small Rain, a mysterious illness seizes, reduces, and ultimately enlightens a poet. While the medical dilemma of the protagonist is harrowing, his rich, compassionate interiority provides succor. “I became a thing without words in those hours, a creature evacuated of soul.” Though Garrard Conley’s transcendent debut, All the World Beside, is ostensibly about an eighteenth century gay love affair between Arthur Lyman, a physician, and Nathaniel Whitfield, a reverend, the novel is chiefly concerned with the nature of desire and the salvation of the soul.

Though Garrard Conley’s transcendent debut, All the World Beside, is ostensibly about an eighteenth century gay love affair between Arthur Lyman, a physician, and Nathaniel Whitfield, a reverend, the novel is chiefly concerned with the nature of desire and the salvation of the soul. Equal parts true crime and an exploration of Florida folktales, veteran journalist Rebecca Renner weaves together a thought-provoking nonfiction debut with Gator Country: Deception, Danger, and Alligators in the Everglades. Renner quickly delivers on the promise of the book’s provocative title, sharing truths more thrilling than fiction as she intertwines impassioned narratives and dispels myths surrounding conservation.

Equal parts true crime and an exploration of Florida folktales, veteran journalist Rebecca Renner weaves together a thought-provoking nonfiction debut with Gator Country: Deception, Danger, and Alligators in the Everglades. Renner quickly delivers on the promise of the book’s provocative title, sharing truths more thrilling than fiction as she intertwines impassioned narratives and dispels myths surrounding conservation.