Anne McGrath’s “Modern Ancestors,” is a series of pieces constructed from mixed materials. See more of Anne’s work on Instagram @TheAnneMcGrath.

Anne McGrath’s “Modern Ancestors,” is a series of pieces constructed from mixed materials. See more of Anne’s work on Instagram @TheAnneMcGrath.

Catherine-Esther Cowie, Heirloom, Mixed Media Collage

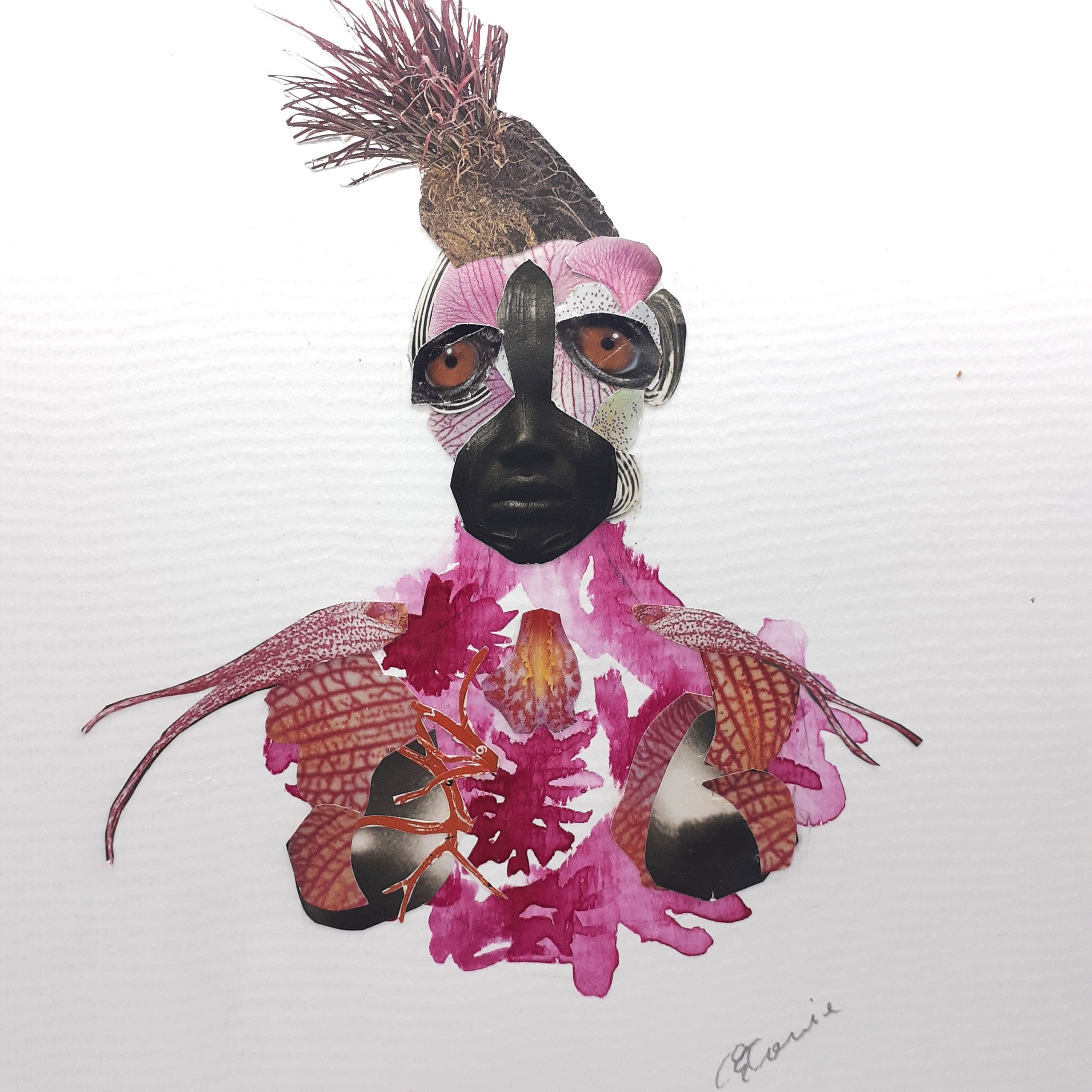

Catherine-Esther Cowie, Auntie G. My Dahomey. My Amazon., Mixed Media Collage

Catherine-Esther Cowie, Hello Again, Blès, Mixed Media Collage

Catherine-Esther Cowie, The Queen of All the Dirt, Mixed Media Collage

I work in collage for its accessibility, for its infinite possibilities beyond working solely in paper but incorporating ink, watercolor, textiles and 3D elements. This series features cut-outs from fashion magazines, images of orchids and magenta India ink. I seek to map the emotional landscapes of my subject matter, women, immigrant women, Caribbean women and the complexity of emotions/states that simultaneously exist: shame and pleasure, loss and strength, beauty and ugliness.

The portraits in this series began as a form of play: I wanted to see how paper and ink could work together. They represent fears, griefs, memories, self-perceptions etc. The piece titled, “Hello Again, Blès” explores how I experience trauma. A sneaky buried wound…then a trigger…through a body now. “Blès” means internal wound in St. Lucian Kwéyòl.

Naming this collection “Heirloom” gestures to a writing project that I am working on that explores what we pass on or give to another generation: ruin and/or redemption. What was carried in the bodies of my mothers: their fears, trauma, loves, afflictions, histories. How some of it is transmitted through story, through their bodies— their way of moving and being in the world. These portraits explore what I carry around in my body…what I may or may not pass on…

These are pages from a book I have been working on from 2003 to the present. This work has slowly revealed itself to be about water, rising water, and human impact on the planet and is part of a larger project called The Sea Museum. The found book that I am altering to make these photomontages was about destroying icebergs, the problem of icebergs, and appears to have been made for children’s education (Danger! Icebergs Ahead! by Lynn Poole and Gray Johnson Poole, Random House, 1961). I’ve always been interested in the absurd, and was feeling a homage to Hanna Hoch, the great Dada artist. I began adding water and related images. I wasn’t working consciously in the beginning, just covering the pages with water. The subject matter feels prescient now, fifteen years in, and I am still altering the book. Like the oceans, this project continues to exist and change.

My artworks and projects focus on ecological subjects, expanding the uses of technologies and capturing environments that escape our sight. These images are samples of two bodies of works. One of titled Paradis, 2018-2019, and the most recent one Dusk/Daybreak, 2020. The images depicted in Paradis make us—the viewers—reconsider ideas of “paradise” with the use of images derived from tropical vegetation that intersect and overlap. Each print is carefully crafted through an experimental digital printing process. In Dusk/Daybreak, there’s an exploration of the landscape through a nontraditional photographic medium. Each print is made through a layering digital printing process. The images make account for the daylight transitions that allow for the visible and the invisible, uncovering mysteries along the Caribbean coast.

I create large-scale audio and visual installations, experimental digital prints, sound arrangements in space, and videos to recreate spaces, memories, and experiences using imagery of natural spaces as a metaphor to understand the complex and interconnected realities we all live. The sources that generate the artworks are mostly research-based in a digital form or archival material that serve to create the installations themselves. Images of obscure natural spaces and elements that define our intimate relationship to spaces—storage containers, sounds, voices, and songs of proclamations in the void—become the aesthetics of the work. Through my artworks and practice I am constantly confronting geopolitical issues, ecology, technology, the act of speculation about the relations that we create to spaces and natural environments. I am always underlining a conceptual framework that comes from my experiences as a Caribbean colonial and post-colonial being as it is in dialogue with the rest of the world.

27 Years, 42 Years, Backbone, and Stitched belong to the Bird Journal Series, a body of work exploring movement and migration due to climate change. As the human impact on the planet increases and pushes the world toward ecological disaster, both animals and people begin to move around the globe in new ways. Birds’ migratory patterns, and even their bodies, are changing in reaction to rising global temperatures.

It is important to me that each drawing, sculpture, or process work be able to stand alone, yet it is in unifying them as one installation that they become stronger still. Similarly, we as humans can and must work together, acknowledging our interconnectedness with each other and with nonhuman beings, to protect the future of the planet.

My endeavor is to pursue a photographic image that embodies natural and immediate expression. My aim is not to produce the sensational or the intellectually novel, but to validate a point of encounter, a tenuous fragment or impression.

The beginning is often a highly chaotic and kinesthetic activity in the process of discovery. I acknowledge a kind of readiness for images more so than the existence of a muse or the notion of inspiration. This readiness requires looking intently at my surroundings; a humility of purpose and acceptance; and a quiet, though often exasperating patience. I do not seek a particular image but rather encourage the image to arrive at my threshold. I allow the light, shadow, color and composition to form organically, in a place somewhere between a vibrant reality and the recesses of my unconscious. I relish this elusive aspect of emergence and honor this transient beginning.

Each photograph evolves in its own unique manner. There is no delineated, predictable order or destination; there are few preconceptions. The initial inception is expanded, combined with newly discovered associations, and gradually finds a voice of intent. Even though I encourage states of intuition, ambiguity, and randomness, I must acknowledge that defining formal or aesthetic decision-making occurs; my creative process is not purely automatic. Formal devices are employed to clarify and strengthen that emotion which first compelled me to photograph. However, any analytic construction is subordinate to the original gestural responsiveness.

In the final image, when the photograph is delivered to the viewer, it is transformed into a new, autonomous existence. And, at its best, the image retains the freshness and spontaneity of the original vision.

My work is contemporary and figurative. Through image-making, I explore what it means to be a human being and to be part of the universal human experience, touching on relationships between people, with nature, and with the environment around us. I see myself and others in a constant cycle, always fracturing, fragmenting, and reassembling ourselves over time. All my work—both art and writing—falls somewhere on this experiential spectrum.

When I begin to paint, I imagine myself walking on a beam of light. I work completely intuitively and without reference to anything around me. I look at the blank canvas and simply begin to draw what I “see.” After sketching the image in pencil, I patch in color. I choose acrylic paint because it dries quickly so that I can paint out and paint over, working in a collage-like fashion. I can also use acrylics to create a stained-glass effect by hand-rubbing areas with very, very thin layers of color.

I know I am on the right track when I feel the presence of some energy, then come into relationship with the canvas as it begins to communicate itself to me. As I transform the original vision, the final piece emerges. I never begin a painting with an idea. The ideas come later.

These 9” by 12” paintings, part of a larger series titled Relationships, are the result of a special challenge I set for myself in 2019. I’d been working on much larger canvases, and I wanted to make smaller, more intimate, almost miniature works. I hoped to prove that a small painting could have as great an impact as a large one.

This digital painting series, “Dispersion,” focuses on the influence of shape on both boundary and color. In all my works I have a “central shape”—an abstract form more or less centered in the composition. I always leave it to the viewer to determine how these shapes read; I don’t dictate meaning. In “Dispersion,” these central shapes are either transparent or teeter on transparency, which infuses them with the surrounding color. This surrounding color extends to the edges. The viewer is therefore invited to participate in a two-part experience; they’re simultaneously introduced to the central shape and the surrounding color, and through that pairing, “disperse” themselves—perceptually, spiritually, intellectually—out to the edges of the image (and maybe beyond them, into infinity). Whether that happens or whether everything stops abruptly depends on the viewer’s initial response to the central shape. In 2001: A Space Odyssey there’s a monolith that emits an ear-piercing tone. These pictures should suggest something similar. Whether they are considered infinite or finite, and despite their four edges and the very specific character of their colors, the viewer should be able to hear them in the mind in a private, interpretive spiritual harmony that Kandinsky called “audible to the soul.”

In this series Mary Tautin Moloney’s poems are inspired by and paired with photographs taken in the subway stations of New York by photographer John Moloney. The work captures the desire to connect alongside the alienation that can come with being alive; how these forces bear on one another and affect us. Mary Tautin Moloney is inspired by what she hears and observes in everyday life: the character of a place; linguistic quirks; her children and motherhood. Her collaborator, photographer John Moloney, is drawn to taking the familiar and making it unfamiliar. In both rural and urban landscapes, he plays with scale, light, and texture to create moments of seeing something for the first time. As one poem leads to the next, a journey emerges through an entirely new landscape, one of the emotional life lived. A touchstone for this project, and Tautin Moloney’s writing in general, is to “cleave to the legendary,” advice once given by Stanley Kunitz to Mark Doty. With this series, photography becomes the entry point for speaking to our larger, shared emotional existence.