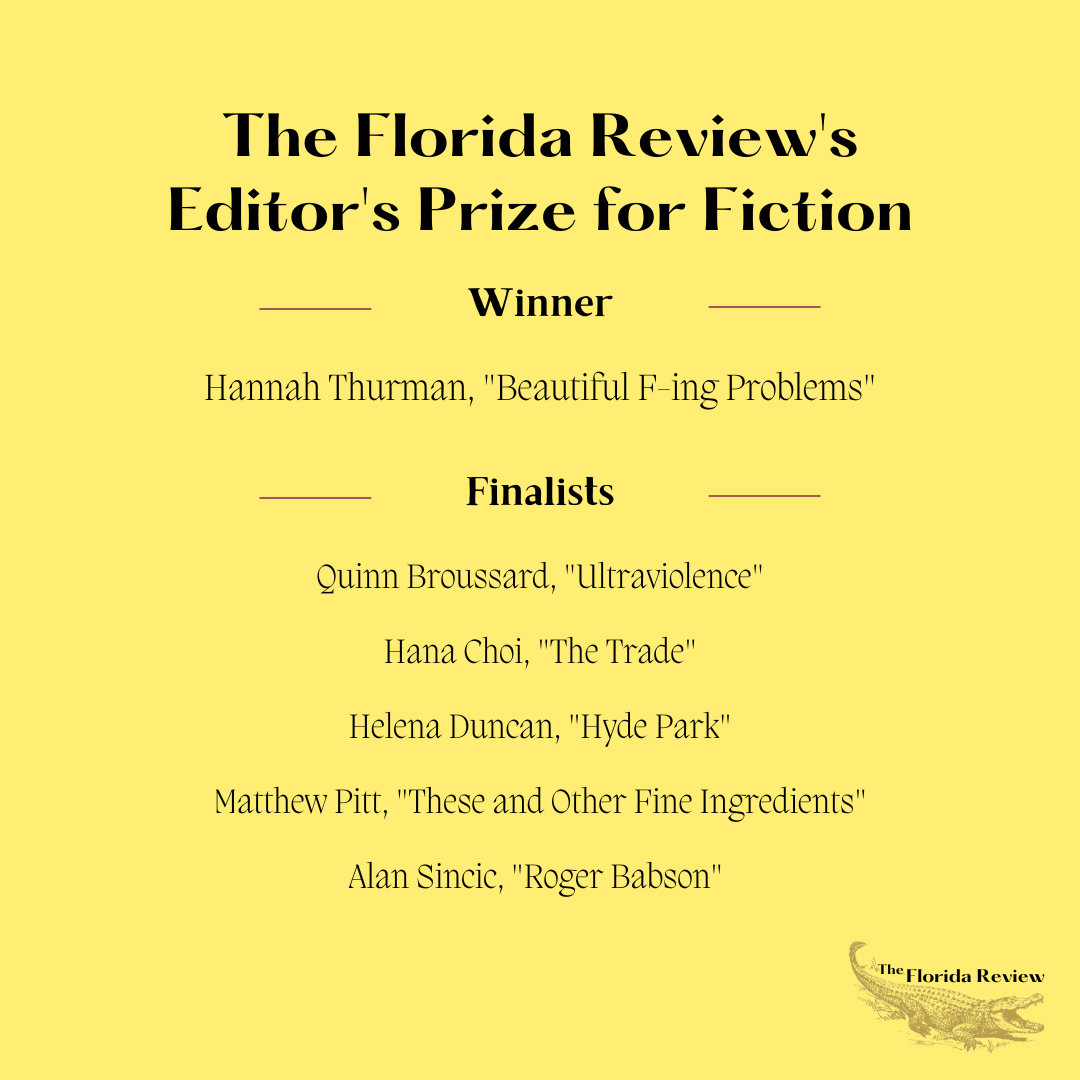

We are thrilled to announce our 2023 Editor’s Prize for Fiction! Congratulations to our winner, Hannah Thurman, and to our finalists, Quinn Broussard, Hana Choi, Helena Duncan, Matthew Pitt, & Alan Sincic.

Category: Literary Features

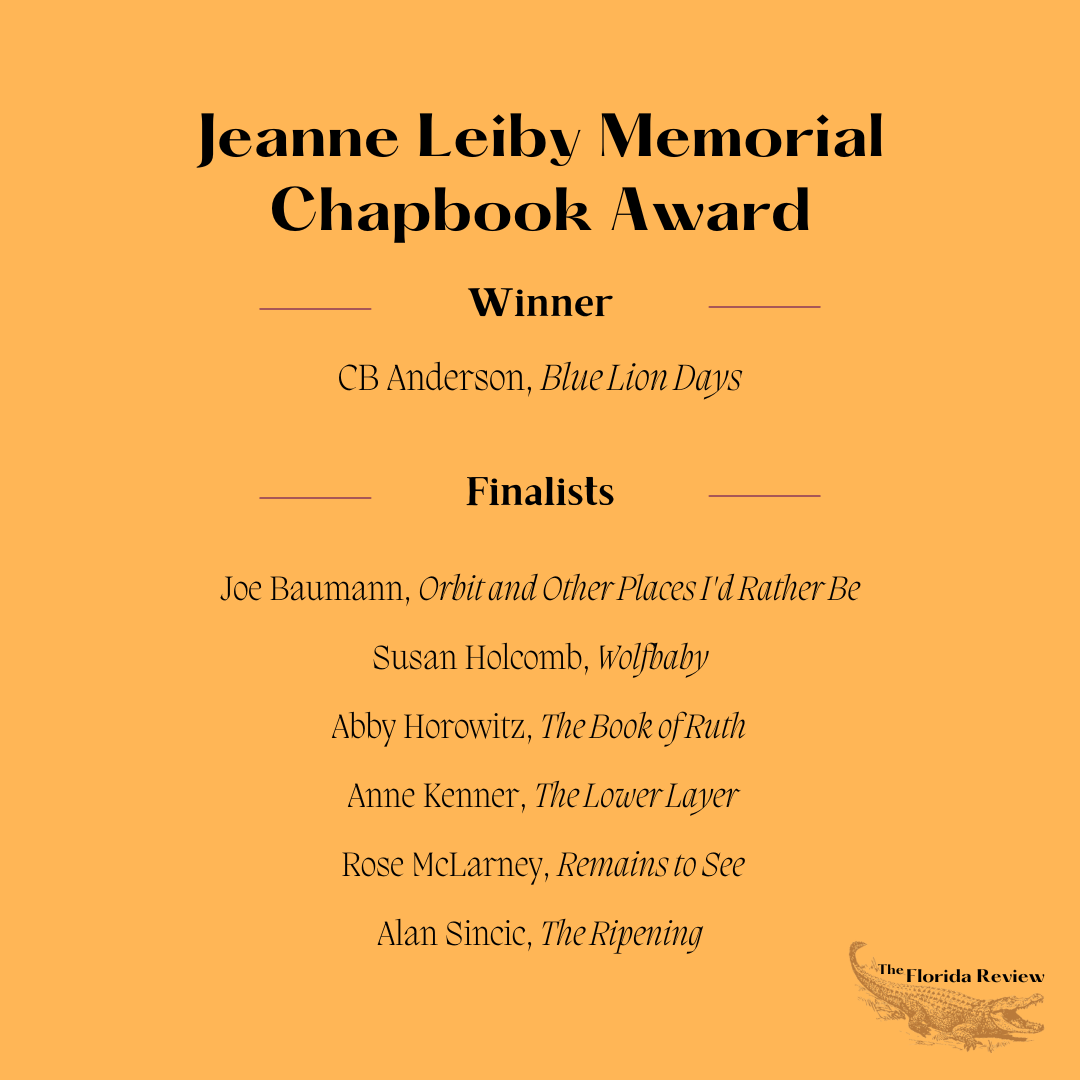

Announcing the Winner of the Jeanne Leiby Memorial Chapbook Award

We are thrilled to announce the Winner and Finalists of the 2022-2023 Jeanne Leiby Memorial Chapbook Award! This award celebrates the life and work of Jeanne Leiby (1967-2007) who served as Editor of The Florida Review from 2004 to 2007. The winning entry will be published as a standalone chapbook in April, 2024. To learn more about Jeanne’s legacy, visit our pages here and here. Thank you to all who submitted pieces for consideration.

The Chili Cook-Off

In the ninth grade my face got all trucked up in a car accident. The next year my high school let me be a judge at their annual chili cook-off. Ever since, on the eve of the season’s first freeze, I make a big pot, the beginning of two months of competition. I find the process soothing. My recipe changes from year to year. I’ve never written it down and being prone to heavy drink, I invariably forget something. My maxim is to keep it simple. This is Omaha. Don’t need to be showing up at the American Legion Hall with braised short-rib chili.

The onset of winter around here is a curious thing. There’s excitement in the air despite everyone knowing that in a month we’ll all be begging for spring. My chili season routine goes as such: on Wednesday I hit the grocery store. Thursday, I dice everything up: onions, peppers, garlic, and tomatoes. Fix a drink. Brown the meat. Refill my drink. Add everything to the stock pot, stir it real good, and let it rest in the fridge overnight. All day Friday I cook it down, adding beer/coffee/broth as needed. On Saturday I bring it to whatever cook-off is happening. Sundays I’m hungover. Monday and Tuesday are pretty inconsequential.

I’ll be up front about it, one of the buddies I was in the car wreck with didn’t make it out. He was sixteen, two years older than me, and he was driving. The other buddy, Tim Slobowski, was my age. We were on a rural stretch of road, what we called out north. Slobowski was ejected from the car. His brain went without oxygen for forty-five minutes, and he spent the next six weeks in a coma. After that they moved him to the Madonna House Rehab Hospital, where he doesn’t know who he is or where he’s at. I used to visit, but it’s been a while.

People at the Hy-Vee see what’s in my cart and give me looks of approval, the man making midweek chili. Such jaunt in my step. My go-to protein is a mixture of Italian sausage and ground beef (1:3). In the past I’ve done some wild experimentation, depending on how frisky I’m feeling. Have used everything from elk to pulled pork to brisket. Where I draw the line is chicken, white chili, which I won’t do. In a few weeks my hunting buddies will start getting last year’s venison out of their deep freezes and I’ll make a few batches with that, but until then, I’ll keep it simple. Italian sausage and ground beef.

As I exit the store, the Salvation Army bell ringer is going at it like he’s John Bonham. I wasn’t planning on donating (no idea where the money goes), but I admire his tenacity. I stop the cart and fish around in my pocket. The drummer does a triplet. He’s wearing fingerless leather gloves. The bell is vise-gripped to a hi-hat stand. He goes at it like a trap set. I bend down with my dollar. He looks at me. We recognize each other. He grins in a way that says he knows it’s me, and yeah dude, it’s him: my old friend, Doogie. He stops mid-song, looks in my cart. “Whoa motherfucker,” he says. “You making chili?”

Aside from family, I’ve known Doogie longer than anyone else. His stepdad coached our little-league team, this mustached dude who’d pitched collegiately and was obsessed with bunting. Later, Doogie and I did drugs and played in punk bands together, which is when he dropped the name William and took on Doogie.

“Doogie,” I say. “What the fuck man, I thought you were in Denver.”

“Made it nine months out there, but I’m back. Been so for a few weeks.”

I nod at the tithing bell. “The hell is this?”

“The fuck’s it look like? Denver’s not cheap.” He lowers his voice. “You still…”

“Gave it up,” I say. “Coming on two years.”

“Congrats. That’s why I moved. Worked for a while too, but you know that junk is everywhere.” He puts a hand on the case of beer in my cart. “Haven’t kicked this, I see.”

“Technically that’s for the chili.”

“Fuckin A.”

“Hey man,” I say. “Is this what it looks like?”

“Not really.” He looks around. “Actually, maybe.”

Ninety percent of my friends from his days are gone. Some left to reinvent themselves and some passed away and some got married, had kids. I spent a decade moving around. Whenever things came close to falling in place, something came up. Emergency dental surgery or a bad breakup or x, y, and z. I pull a twenty from my billfold. Doogie pockets it on the sly and gives the bell a thwack, thanks me for being a good friend.

In the three years I’ve been back in Omaha, I’ve entered forty chili cook-offs. Placed in the top three at thirty of them, fifteen of which I won. I know it’s a weird hobby, but if my biggest proclivity is an obsession with making chili, I consider myself healthy. It’s Thursday morning and my stomach is weightless in anticipation. Been since March that I last made a batch. I hone the chef’s knife, ready the cutting board. The tips of my fingers get prickly. I start my audiobook: Stephen Covey’s The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. It’s been my soundtrack for the last two chili-cooking seasons. Over the next couple months I’ll take it to the house three, maybe four times. Put it away for the year, recharged.

I am in control of what defines me. Covey hammers that. Don’t have to be defined by my past. Humans have the power to choose. That’s why I moved away. Fuckers all saw me as the dude that had been in the car accident. For many years I was erratic. Covey helped me regain control. It’s like he says, so much about who we are is determined in the split seconds between stimulus and response. And never forget that you have the power to choose.

The baseball team that Doogie and I played for—the Omaha Tornadoes—the summer after sixth grade we made a run at the Little League World Series, the event that’s televised on ESPN. All season we used the thought of ourselves on TV as motivation. A communal fantasy that grew out of control. We made it to the final round of regionals in Wichita, KS. One more and we were in. We could practically see ourselves in the nation’s living rooms, dominating with small ball. The hope for a better tomorrow. We ended up losing in the last inning of the championship game and shortly thereafter found out that we hadn’t even been competing in the tournament that climaxes on ESPN. We’d been in some rinky-dink knockoff version, lied to by our parents and Doogie’s stepdad, who knew we’d be motivated by TV. The whole experience ruined baseball for me.

I love waking up on chili cook-down Friday. Last night it was hard to fall asleep, similar to the last day of school as a kid, a memory I barely remember, but it was embryonic, the windows open to perfect weather. I put the pot on the range and slowly bring it to a boil, stirring in cumin, cayenne, and paprika. Half a Hershey bar. A quarter cup of cold brew. Couple tablespoons of Mexican coke. Last year I fucked around with soda syrup as the sweetener. It was close to what I wanted, but the line to toe was thin and it made me feel like I was trying to be something I’m not, unbearably pretentious.

All told I spent a decade away from Omaha. Went from Tampa to Lake Charles, Asheville and Pensacola—once for love, once for a bar, and the others for no real reason, reinventing who I was every few years. One of the things I consistently missed were the chili cook-offs, nothing like they are in the heartland. To the credit of Lake Charles, they had a bunch of well-attended gumbo cook-offs around Mardi Gras, but I only like that stuff in extreme moderation. At the last one I attended I was eating a bowl in front of the guy that made it—duck and andouille—and on my second spoonful I bit square into a piece of buckshot. I pulled the BB from my mouth and the guy started laughing like a goddamn maniac. I didn’t think it was funny, though. That incisor is still chipped.

I bring the chili to a hard boil and kill the heat. Add in some bone broth and work it to a simmer. I can’t stress enough the importance of a quality stock pot. I’ve got a top-end chef’s knife as well, German forged steel. Those Japanese brands look sweet, but I’ve heard they require a ton of maintenance. Even though it’s been years since my last relationship fell apart, I still fantasize about the gift registry she and I put together, sorry we didn’t stay together long enough to see it through. The kitchen we would’ve had.

The cook-off they let me judge after my accident was our high-school’s big annual fundraiser, climax of the blue-and-white weekend. The three judges are usually big-time alumni. It’s considered an honor. That’s what my mom kept harping on after I was invited. I was hesitant, but she insisted. And she was right. Whole crowd gave me a standing-o when I took my place. I was seated next to a famous movie director, class of ‘79. He’d just finished filming something with Matt Damon. It’d been the talk of our high school. The emcee put two flights of chili in front of me. The director noticed my shaking hands, leaned in and said that Matt Damon had found my story very compelling. By the time I reached the next taster, I’d settled down. I took a bite and pretended to gag, real cartoon-like. At that moment everyone in the audience knew I’d be fine. They beamed up at me, proud of the way they’d rallied around the poor kid. Helped him overcome adversity. Many years later I drunkenly tried getting in touch with the director to see if he could help me out. His people said he was on location in Hawaii, and that if he didn’t get back to me in a few months, to follow up. But he didn’t and neither did I. The whole thing was stupid. What was I expecting, him to cast me in some fucking Jason Bourne movie?

After three hours of simmering, I give the chili my inaugural taste. Swish it around like a wine snob. As anticipated, there’s something missing. Always happens with the season’s first batch. Last weekend I emptied my pantry, which I do at the beginning of every October, keep the spices and toss the rest—hard to innovate while constipated with yesterday’s shortcomings. The pitfall is that this chili needs something I don’t have. It’s no problem, though. Hy-Vee is close and maybe I’ll get to see Doogie again. Been thinking a lot about how I got off the path we were on and he didn’t. The emptiness he must be feeling. I’ve been there.

After the dust from the car wreck settled my parents hired an attorney. The hairpin turn we wrecked at wasn’t labeled. No guard rail either. Everyone’s assumption was that we’d been drinking, but we hadn’t been. My buddies and I were just out for a joy ride, Nebraska in early April, looking for sandhill cranes. When we launched off the road my stomach shot through my throat. Time elongated into milliseconds I could see and touch. There wasn’t any calm or clarity, or whatever people tell you they feel in the moments before death. It’s all a lie. I only felt terror and all I wanted was to be alive. Then we crashed in a soy field and started rolling. My attorney was a real bulldog. The county was on the hook. My folks put my settlement money into a trust. Every month until I turn forty I get two grand. It’s been a blessing and a curse.

This time when I approach the entrance to the grocery store there’s no Salvation Army bell ringer. Honestly, I’m disappointed. The vision of Doogie’s face has been in the back of my mind. How worn down it looked, like an old catcher’s mitt. I shouldn’t have left him in the lurch all those years ago when I up and moved away, cutting ties with who I was. From eighteen to twenty-five, he and I travelled the country pursuing punk-rock fantasies. Taught a bunch of shit-hole bars a thing or two about having a good time. Made caricatures of ourselves and called it profound. Swore we were pursuing the life we wanted, fast and hard. Paycheck to paycheck. Then the pixie dust wore off and I moved away without saying much. Just needed a change.

I meander through the grocery store. Grab some high-end bone broth, a couple ghost peppers, another can of tomato paste. An orange (for the zest). When I’m leaving the store I hear someone wailing on the bell. I’m thrilled. Can barely contain myself as I turn toward him. He’s wearing a necktie as a headband, Judas Priest long sleeve under the Salvation Army vest. Drums a line of blast beats.

“Doogie!”

“My dude. Back again.”

“Needed a few things for my chili,” I say. “How’s it going, man?”

“Nice as shit out today. I’ve been trying to figure out if there’s any correlation between weather and generosity. Far as I can tell, it’s random.” He swings the donation kettle back and forth. “Bunch of fucking cheapskates.”

“Dude, you know what I was thinking about after I saw you the other day? Remember that year we almost went to the Little League World Series?”

“Twenty-three years ago,” he says. “It’s like they say, time flies when you’re having fun.”

“You want to ditch this and come over for some chili?”

He fidgets around. “Got any of that beer left?”

“Eighteen at least.”

He removes his vest and says, “I’ll hop in with you.”

The neighborhoods we used to live in are nice now, full of street tacos and cocktail bars. Our drug house was gutted and turned into a vinyl-listening library, $79 a month, one of the best record collections in the Midwest. When we lived there, we were constantly having to scrape together extra money to get the utilities turned back on. Place had revolving doors. My room was on the top floor. Doogie’s drum set was in the basement. Despite sound proofing it with egg cartons and junked mattresses, I heard every beat of his practices, and he was always at it. Ever since I’ve needed a box fan to sleep, that dump was so loud all the time. Makes me glad it’s something pretentious now.

Immediately upon entering my house, Doogie says, “Good fuck. It smells fantastic.” He checks out my trinkets. I’m a collector of several things. Bobbleheads and postcards and koozies, most extensively. When I started accumulating them, I stopped getting tattoos. Win-win. I’ve got koozies from all over the country. Some from places Doogie and I went together, like the bar in the lobby of the heart-shaped hot-tub motel in Jackson, MS. First time we tried meth.

“You really hate having a warm beer and a cold hand,” he says, looking at all of them. “I’ll give you that much.”

“See the one from Slims in Raleigh?” I say. “That place was insane.”

“Oh man, I still feel bad for that guy. Dude who put us up. He didn’t deserve that from us.”

“Yeah,” I say. “I forgot about that. Certainly not my proudest moment, but he had money and was an asshole to begin with.”

I get us a couple cans of beer. The chili is simmering on the range. I prepare the fixins: a bowl of Fritos, Crystal and Tabasco hot sauce, fine-shredded cheddar. In Nebraska it’s customary to serve cinnamon rolls with chili—they get us started on it in elementary school—but I don’t play by those rules. Fuck that. I put the chili in front of us, normal fixins. Before taking his first bite, Doogie wafts it under his nose. “What’s that I detect,” he says, “nutmeg?”

“Maybe.”

He wolfs the bowl down without another word. I’d go so far as to say I knocked it out of the park. Again.

“Well,” he says. “Pretty decent.”

“Pretty decent? Variations of this recipe are going to win a ton of cook-offs.”

“I’m no chef de cuisine, but it seems like you over handled it a bit. Folks want a robust, simple chili. This tastes like it doesn’t know what it wants to be. You know what I mean? It lacks an identity.”

“Yeah?”

“The fuck do I know, though, I’m a Hormel man.”

“Get out of here with that. Seriously?”

“You like what you like.”

The guy’s got dirt under his fingernails, sniffles a lot. Almost forty-years old and still rocking a Judas Priest shirt. He’s as lost as I once was, an addict. I shouldn’t fault him for the Hormel comment. He doesn’t know any better. I grab us another couple beers. “Listen,” I tell him. “I think I’ve got something that could help you out.”

“Less cumin in the chili?”

“Funny,” I say. “I’m trying to be serious for a second.”

I keep several copies of Seven Habits around the house for this very occasion, a friend in need. I hand him the multi-disc audio edition. He holds it like a problem child with the body of Christ. “You might think it’s bullshit,” I say. “But it worked for me.”

“Worked like how?”

“Helped me get in control of everything. I had a victim’s mentality for pretty much my whole life. Bad things kept happening to me because bad things always happen to me. You know what I mean? That type of philosophical outlook.”

“Fuckin A,” he says.

“Friend to friend, I’ve been where you’re at.”

“Look, man,” he says. “I thought we were here to eat chili. If I wanted to be proselytized, there’s any number of people more qualified than you that I could’ve gone to. No offense.”

“Trust me, I was the same way. This shit, it can take a load off.”

“That’s not the point.”

“What is the point?”

“I don’t want unsolicited life advice. Especially from someone like you.”

He’s the same way I was, hardheaded. Covey helped me realize that.

“Just take it,” I say. “Do whatever you want with it. Doesn’t matter to me. But take it, just in case.”

—

I won the first two cook-offs of the season. Spent three weeks honing my recipe and then boom, I took O’Leavers on the first Saturday in November—$100 bar tab—and The Winchester the following weekend, where this biker in his seventies finished second. By the time they announced the results the biker was damn near incoherent, prison-sleeved and in the throes of what appeared to be a psychedelic trip. For winning that one I got a toilet trophy and fifty bucks. The biker got a bottle of blackberry brandy. He had a tough time figuring out what it was.

I am a well-oiled machine. My house smells delicious all the time. If they made a chili-scented candle, I’d be the target demographic.

I kicked the shit out of The Sydney’s cook-off. They never stood a chance. Two different yahoos had chickpeas in their chili. To them I said, “Why does the sexual deviant like your chili so much?”

Huh?

“Because the chickpeas.”

And I rode off into the sunset, gift card in my pocket.

Bribery and ass kissing are rampant in the competitive chili scene. It’s always better to have a panel of judges than audience voting. No telling whose team folks are on. Another pro tip: invest in a decent crockpot. Nothing too expensive, but nothing too shitty. People judge at either end. What can I say, they eat with their eyes. And if the cook-off benefits charity, do a little research first. Or just avoid them altogether. They bring out some serious amateurs. The ones at old-school bars are where it’s at.

Oh, and don’t show up with bean-less chili. Whenever someone does, we talk shit behind their backs.

I open the year six for eight. Lost two to charity, but what the hell, they were for good causes. Not like it’s my fault that the parents of the Kingswood Athletic Association have unsophisticated palettes. Keep your crown, you well-done assholes. And never again lie about how the baseball season could end. None of those cook-offs matter anyways. My green jacket, the creme de la creme, is this weekend at the Homy Inn. Culmination of the season. The place is an institution, beloved by the types of lawyers/doctors/rich folk who give big at my high school’s annual fundraiser. While most cook-offs get between ten and twenty entrants, the Homy will have upwards of fifty, judged in stages. $500 on the line. I’ve never won. Last year I took third. For it I’m breaking out the big guns. I started my prep work a week ago. Went and bought a pork butt that I cut into inch-thick strips. They’ve been curing in crab boil and canning salt in the fridge, a cup of sugar. I’ll smoke the slabs into tasso a few weeks from now. What I’m after in the meantime are the shoulder blades. Left a good amount of meat on them. They’ve been in the curing solution. I’ll add them to the chili at the very beginning, let them season everything. All told it’s a two-week process.

They ought to crown me champion now, Friday afternoon. This batch is incredible. The pork bones worked wonders. After a few hours of simmering, I was able to shred the meat right off. It’s got a feathery texture, packed with flavor. Perfect complement to the Italian sausage and ground sirloin. I should’ve been writing down my recipes all along. For posterity. Maybe open up a chili parlor someday. Write a cookbook and have Matt Damon blurb it. At the very least, I’d be able to see what the changes say about who I became, no longer the brooding dude on the verge of an episode. I am the chili master now.

On Homy Inn Saturday I wake up at the crack of the sparrow. Begin the day with thirty minutes of yoga on YouTube. Follow that up with fifteen minutes of mindfulness, guided by YouTube. Then I take a hot shower. After the shower I pull the chili from the fridge and put it on the range, slowly bring it to temperature. I eat a bowl straight up, no garnishes. Phenomenal stuff.

The cook-off starts at two. I show up at one, bring it in the front door. The bartender takes it to the back, where they’ll transfer it to a quarter tray, to be labeled and served from steam tables. The right way to do things. Total anonymity. I settle into the bar, have a beer and a shot. My chili might be superfluous, but when it comes to drinking, I’m a meat and potatoes guy. More and more people arrive with chili. Some look like straight-up yokels. I rule them out. The rough looking ones are the ones I’m worried about. That old-timer with the neck tattoo, for example, he ought to get a first-round bye. Respect for the lifers. The bar’s capacity is a tight 175. Today they’ll reach that. The bartender brings me another beer and addresses me by name, asks how my chili turned out.

“Pretty good,” I say.

I’m tempted to tell him how awesome it is, but I’ve overheard a bunch of contestants running their mouths and in this arena I want to be the strong and silent type. As Covey would say, the choice is mine.

Forty chilis have been entered. The bar is wall-to-wall. A couple sore-thumb tourists pump money into the claw machine, nothing in it but a big pink dildo. What a dive, they laugh. Folks always act surprised when they realize said dildo is greased, which should probably be a given. The Homy has been putting this on for over twenty years. They’ve got it down pat. Chilis have been separated into groups of ten. The first round will be judged by the audience. Every attendee has been assigned a flight and given a scorecard. Top three from each will advance.

Minutes before it’s about to start, the front door swings open. Standing in the gust of frigid air is my old friend Doogie. He’s carrying a greasy crockpot, balances it against his stomach with one hand. Fist bumps the door guy with the other, who then hustles it to the back. Doogie catches sight of me. I raise my glass. He gives me a stern-faced thumbs up, goes and registers with the event coordinator—the octogenarian proprietress who takes absolutely no shit from anyone. For the past fifteen years she’s made a pot of chili for people to eat during Monday Night Football and for my two cents, it’s pretty good. I expect her to give Doogie a hard time, but she doesn’t. In fact, they seem to have a rapport. He comes to my side and orders a drink and I say to him, “Didn’t know you were into making chili. Which number is yours?”

“You know it’s against the rules for me to divulge that information prior to the completion of first-round voting. I may be a fuck up, but I’m no cheater.”

“What do you say we get a little side bet going?”

“I don’t approach making chili with a results-based mindset. I trust what I cooked. For me, the joy is in the process.”

“You listened to the book,” I say. “Awesome, man.”

It’s vintage Covey. Always act with the end in mind.

“The hell I did,” he says. “What’s the bet? I’ll take your action all day.”

“Forget about it. You’re right about being process based. It’s all in good fun. I’m glad to see you’re doing well.”

“Five-hundred,” he says.

“You’re good for that?”

“Here he goes again, Mr. Shit-Together.”

He does look healthier. Not as strung out.

“Fine,” I say. “Five-hundred it is.”

I’ll take this dickhead’s money. Kickstart him into helping himself.

“I don’t even care for chili,” he says, “but having tasted yours, I know I can beat it. Someone has to put you in your place.”

“Yeah?”

“See you at the finish line, asshole.”

I’m starting to remember why we had a falling out. Dude’s kind of a prick. Only reason he started at second on our little-league team was because his stepdad was the coach, the mustached man who orchestrated the whole ESPN lie. I’m sorry to say it, but his stepson is about to lose five-hundred bucks.

Will I make him pay?

Goddamn right.

The emcee starts the event. First round will take an hour. It’s warm in the bar, spirited. These things aren’t really about winning. They’re about Midwestern camaraderie. The shared misery of another winter, born to die in Nebraska. This bar regular I’m friendly with, Rat-faced Johnny, plays Motörhead from the jukebox. He knows I’m a fan. “Here’s to pissing in the wind and shitting where you eat,” he says. Motörhead ends and Iron Maiden comes on. Rat-faced Johnny does it again.

I sample all ten chilis I’ve been assigned. Have a sip of Aperol spritz between each. Don’t care if the drink looks ostentatious, it’s a great way to cleanse the palette. Three of the chilis are decent. Four are palatable. And three are downright lousy. If they’re any indication as to how these people eat at home, I feel sorry for them. No doubt I’ll advance to the next round.

Doogie shuffles to my side and says, “I know which one is yours. Heavy on the cumin again.”

Before I can retort, the bartender cuts the jukebox—Rat-faced Johnny is not amused, middle of his favorite Black Sabbath song—but they’re ready to announce the first-round results.

“You think you made it through?” I ask Doogie.

“At this point,” he says, “it’s outside my control and therefore, I am unconcerned.”

Another of Covey’s tenets. Even if he’s mocking it, at least he listened.

“By the way,” I say. “That was a bullshit move your stepdad pulled. Convincing us we were going to the Little League World Series.”

“You’re telling me,” he says. “I had to live with the fucker.”

The emcee fumbles around with the PA system. People are mirthful. Days are getting longer. We’re past the peak of winter. In no particular order, the emcee calls the numbers of those that have advanced into the finals. Of course I am among them. Doogie stays calm throughout. “You make it through?” I ask.

“Man,” he says. “Why’d you have to bring up my stepdad? I’m not trying to think about that guy right now. Fucking ruined my day. That’s a bullshit move.”

The last thing I expected was tenderness. “You’ve been a prick all afternoon,” I say. “I was just giving it back.”

“I know why you’re obsessed with this chili cook-off bullshit. It’s because they let you judge that one in high school after the accident went down. Got me thinking, man, when’s the last time you’ve been out to see Slobowski?”

He knows not to go there. I shake my head.

“Just a question,” he says. “I’m genuinely curious.”

“You know the answer.”

It’s not a conversation I care to have with anyone, let alone an old junky buddy.

“Anyways,” he says, eagle eyeing the barroom. “I’ve got to go catch up with some folks. Good luck with the next round.”

The bartender kicks the jukebox back on. Rat-faced Johnny raises hell, says it skipped his songs and ate the remaining credits. Now it’s playing some bullshit Aerosmith song and everybody in the state of Nebraska knows he hates them. Johnny’s nickname isn’t flattering, but it sure does fit. The bartender tells him to settle down. Not like the jukebox is going anywhere.

The judges take their places at the head table. Two of them I recognize, the chef from the Boiler Room and this stout guy named Dario, owner of Dario’s. Best steak frites in town. The third judge I’ve never seen before, some lady who teaches culinary arts at the community college. Over the years I’ve learned not to overthink what the judges might be thinking. There’s nothing their reactions can tell me about chili that I don’t already know. I lean back and enjoy my spritz. Peace be the journey. I order a refill on Doogie’s tab.

The judges head to the backroom to deliberate. I sample all ten of the finalists. Seven are solid. Sometimes I get too cocky and underestimate my competition. Wouldn’t be the first time hubris has fucked me. Three of them even, I wouldn’t be ashamed to lose to. One seems to have hit exactly what it’s going for. Perfect combination of heat and flavor. This brilliant texture to it. Oh wait, it’s mine.

Nice.

The judges emerge with their results. The emcee has an envelope in hand. He delivers a little hoopla. Thanks us for being here. Says they couldn’t have asked for a more qualified panel of judges. And what a way to kick off the homestretch to Spring. My nerves ratchet up, suspended in the in-between while this guy finishes his spiel.

No matter the outcome, I know in my heart of hearts that I am a winner.

I advance into the top five. Those that have been eliminated go and collect their consolation ribbons. The emcee whittles out two more. I’m in the top three. Soon they’ll be etching my name on the plaque, forever part of something bigger than myself. Doogie is stone-faced. I have no idea if his chili is still alive.

Just name the goddamn winner already.

And then they do.

William “Doogie” Donahue.

The audience gives it up for him.

Son of a bitch.

He tries to accept it stoically, but has a teenager’s sheepishness when he takes the trophy. Looks out into the crowd and raises his arms. I’m pissed off, but oh well. I’ve got to admit, his chili, #6 of the finalists, was good. Nice and hearty. Midwestern. I put my hands together for him, my old friend.

There’s always next year and the next year and the one after that. Adapt and survive. Maybe I’ll open a chili parlor when my two-grand allowance runs out, call it Slobowski’s. I’ll go out to the Madonna House to see him soon. It’d be nice to catch up with his mother as well. I know she was bummed when I quit visiting, disappeared in pursuit of something I never found. Didn’t even bother returning her calls. But I’m back in control now, helping old friends win chili cook-offs. Some much-needed meaning in Doogie’s life.

The bar settles down. Empties by about half. It’s 4:30 now. In an hour it’ll be dark. For finishing second I got a $200 tab, which I’m putting to good use. Gave rat-faced Johnny permission to drink on it until it’s gone. Would’ve thought he won the lottery when I told him.

“It was a well-fought battle.” Doogie comes up and shakes my hand.

“You showed me,” I say. “I apologize. Got ahead of myself.” It’s important that I be the bigger man. “You do Venmo?”

“Cash only, bucko.”

He follows me to the ATM. I hand him the five hundred and say, “I guess we’ll see each other when we see each other. Until then, be well.”

“You know what my chili was?”

“What?”

“Just Hormel that I doctored up a little bit, you self-righteous son of a bitch.”

“Motherfucker.”

He walks away—middle finger up—out into the dregs of winter, a champion.

The Purported Magic of Broccolini

When, on several occasions, my Twitter crush tweets that he’s eating broccolini, I feel intrigued. I’ve eaten broccolini a couple of times, in restaurants, but never prepared it at home. I begin looking for broccolini each time I visit the grocery store, with no luck. After two months, broccolini becomes available from my online imperfect produce delivery. Jackpot!

I become very excited about the broccolini, which I must wait three days to receive. Although I’m no longer in full pandemic isolation mode, I work from home, am single, and see friends only occasionally. Most of my waking life is spent indoors, staring at a screen, or on long, slow walks that I hope counterbalance those other hours.

To combat loneliness and keep my spirits up, I try to give myself a continual stream of small thrills — walking a new route, photographing a neighbor’s rose mallow hibiscus bush, listening to a musician I’ve never heard before, and, now, exploring the purported magic of broccolini.

I search for information about broccolini online to fuel my excitement as I wait for the order to arrive, like a child would research a gift they are expecting for Christmas. I know what I’m doing is a little silly, a contrived effort laid forth as part of a larger attempt to maintain mental and emotional health. But don’t we all need a little silliness sometimes? For me, at least, researching broccolini has healing properties.

Since I’d heard broccolini referred to as “baby broccoli,” I’d mistakenly thought it was the broccoli plant harvested at a young age. But I learn broccolini is not young broccoli. It’s actually a hybrid of broccoli and gai lan, another Brassica vegetable also called Chinese kale or Chinese broccoli.

Further, the word broccolini is trademarked. This hybrid vegetable, only legally allowed to be referred to as “broccolini” by the company Mann Packing, is nutritionally similar to broccoli, providing protein, fiber, iron, and potassium. But because broccolini is denser, you’d need to eat nearly twice as much broccoli to receive the same amount of nutrients.

Mann Packing isn’t the only brand that trademarked a term for my virtual crush’s favorite veggie, though they seem to be the most successful. Other companies have trademarked “bimi” and the aptly named “tenderstem.” Those who prefer not to use branded terms for this piece of produce may call it broccoletti, Italian sprouting broccoli, aspiration, and — my personal favorite, albeit slightly inaccurate — sweet baby broccoli.

When my broccolini arrives, it looks slim and long. The stems end in playfully floppy, round florets. After examining it closely, I put my broccolini in the fridge. When I take it out the next day at dinnertime, I see that tiny yellow flowers have bloomed around the edges overnight. An internet search shows the yellow flowers indicate the broccolini has aged, but is still safe to eat.

I sautee the broccolini in oil for only a few minutes as the internet had instructed, strain it, and spoon it into a bowl. Although I rarely use butter, I drop a pat on top of the slightly charred aspiration, watching the pale yellow square melt onto the green stems and bright yellow flowers. I squeeze a few drops of juice from a halved lemon over the dish, then grind sea salt on top.

I decide to eat my long-awaited broccolini at the dining room table, like it’s special, like I’m special, and not someone who eats most meals either at her desk while looking at the computer or on the couch while watching television.

The first bite is soft and warm on my tongue. I eat slowly, with my eyes closed. The richness of butter, the tang of lemon, make the vegetable taste luxurious, sultry even.

All of my excited preparation no longer feels the least bit silly. My effort was well worth it. The broccolini tastes like I picked it on a walk through a field rather than ordered it online. As if I prepared it over an open flame outdoors rather than in a suburban kitchen. I feel like I’m in a fairy tale — “The Woman Who Eats Yellow Flowers” — and I don’t want to leave.

I consider standing back up to get my phone for the purpose of taking a photo of the dish and tweeting it at him with the text, “You’re an influencer!”

I refrain. This moment is mine.

Two Poems

Halloween: Ends

Michael Myers at the 711 filling up his SUV.

Michael Myers at Home Depot buying fancy drill bits he doesn’t really need.

Michael Myers sitting in the back of the room at the PTA meeting, scrolling through Tinder.

Michael Myers doing taxes.

Michael Myers scrolling through Facebook in the movie theater.

Michael Myers at couple’s counseling.

Michael Myers letting the dog out one night and telling the kids it ran away.

Michael Myers killing all the sex workers in Grand Theft Auto.

Michael Myers sitting in the back pew at church, scrolling through Tinder.

Michael Myers mowing the lawn on a beautiful Sunday afternoon.

Michael Myers wearing an apron that says I Rub My Own Meat.

Michael Myers getting drunk at his Superbowl party.

Michael Myers explaining the differences between a bratwurst and a sausage to a woman looking at her phone.

Michael Myers renting Saw IV again on Amazon Prime.

Michael Myers taking his mask off to have sex but leaving his socks on.

Michael Myers toweling off in the locker room.

Michael Myers rubbing against people on the train.

Michael Myers at the hotel bar explaining the difference between bourbon and whisky to a woman looking at her phone.

Michael Myers calling up toiletries and answering the door in his bathrobe each time.

Michael Myers ordering his burger well-done.

Michael Myers sending his food back twice.

Michael Myers not tipping.

Another autumn

after Mikey Swanberg

walking the mile

to work,

freezing in the morning,

sweating on the way back,

each step a stitch

quilting the heavy blanket

of our unhappiness.

Nothing has happened,

and still—

I imagined my lover

might show up

in my office

before I left,

shut the door

and we would fuck

quietly on the desk

to the rhythm

of the copy machine.

In another version,

he’d walk out to me

halfway along the mile,

stitching his own path,

and say something

he was never going to say,

that he had changed, and I

had changed, but

all for the better,

and we were stronger for it,

as though love

were a sourdough,

dying then restarting,

grown through being given away.

How long did I believe that time

was the most costly thing.

What a hard bargain

to find it is the only thing.

75 Simple Steps to Positive, Growing Change

1. Consider not reading the e-mail from your cousin Tommy, but then read it. Discover that your Uncle Dave has died. Of an embolism. Very unexpected, as is the case with these things. The e-mail notes the date, time, and location of the funeral. It is signed “best, Tommy.” Struggle with how this makes you feel. It’s been at least ten years since you’ve seen any of your relatives. Your mother’s funeral was the last time. You can’t believe how long it’s been. Ask yourself what you’ve even been doing in all that time. Decompressing is the only answer that comes to mind.

2. Take a Greyhound to Harrisburg to share Tommy’s grief as well as the grief of your Aunt Joan and Tommy’s twin sister Linda. Your own grief is of course less severe than theirs, but you are family and are grieving in appropriate amounts. Think about how your mother would have admonished you if you told her that the funeral were being held at a particularly bad time in your life, making it very inconvenient for you to attend.

3. Struggle to maintain your composure during the service, which is as anxiety inducing as anyone could have purposely arranged. Wonder who these people are. Assume they’re probably wondering the same about you. Shake hands with Tommy but don’t approach Linda or Aunt Joan, who seem almost too bereft at the cemetery, under a purpling sky that feels so close you could touch it. Imagine yourself being carried off by birds.

4. After the service, just as it begins to rain, accept a ride to the house from one of the other funeral attendees, a solemn man in his 50s, perhaps a business acquaintance of Uncle Dave’s. Tell him that you are the nephew. Smile and nod when he says, “Oh, the one from the city.” Thank him for his kindness when he offers his condolences. In the car, a twenty-year-old Acura kept in good trim, when he asks whether you mind if he smokes, ask him whether he minds if you vomit. Drive the rest of the way in silence.

5. Stand in the living room eating finger foods and drinking cocktails. The rain is falling in unbroken sheets, white noise humming in the background like classical music played at low volume. The boyfriend or fiancée of one of Linda’s friends, Dom or Don or something, hovers by the rolling bar and threatens with a drink anyone who ventures too close. Due mostly to these predations you’re on your third gin and tonic, which he keeps calling G&Ts. “Need another G&T?” he asks, you’re sure only trying to be of help in your family’s time of need. “Looking a little dry there, my man.” Watch him pick up some ice cubes with his fingers, which someone really ought to talk to him about—the tongs are right there. But, trying not to think about vectors of germ transmission, accept the drink, thank him, and then stand inconspicuously in front of a cluster of family photos. The largest photo is of Linda and Tommy at Epcot Center in their 90s clothes, lorded over by Uncle Dave and Aunt Joan. Picture their teenage resentment as a heavy, opaque liquid oozing right out of the photo.

6. Notice how the house feels like a place of pretty negative juju. Likewise Harrisburg in general, which you haven’t visited since you yourself wore appalling 90s clothes. You’ve come to associate both the house and Harrisburg with many painful instances of youth. Recall the day in 1992 when Uncle Dave body shamed you in front of basically the whole family. How afterwards you’d imagine him stealing away into the night to gleefully commit crimes. You did this to deflect his criticism, to make these the savage words of a vile criminal rather than the casual insults of a family member. But also, if he had no compunctions about reducing his only nephew to tears, imagine what he must have been capable of doing to complete strangers. Or his children. Looking at the raggedy group of mourners, wonder what they actually know about him. Walk to the buffet table to gnaw on a baby carrot.

7. While gnawing, try to remember past instances of positivity and bonding with your cousins since they are currently consumed by grief. Or so you imagine. Your uncle was not a warm man. No one would ever have said that about him, yet here people are in his home, or more correctly former home, celebrating his life. Recall a weekend visit when Uncle Dave pulled Tommy’s arm behind his back at a cruel angle for some offhand comment he’d made about the Penguins. How Linda had tried to intervene while you only sat there frozen to the spot. Remember how she yelled, “Let him go, Dad!” and the speed with which he then turned his anger on her for merely trying to defend her brother. Over hockey, no less!

8. Recall how you dissociated from the scene, even though back then you lacked the word for it. How you saw it instead as a tableau, not anything you were involved in or even necessarily present for. Witness it from a remove, as though watching it on TV or through the illuminated dining room window of a house you are walking past at night. Note your uncle’s hair, how the word that comes to mind is “yellow” rather than “blond.” See Aunt Joan smiling nervously—but at who? At you?—as though this gesture would exonerate Dave, excusing his behavior—his violence towards his children, to call it what it was—as a small peccadillo, as “Oh, you know how Dave gets sometimes.” See Tommy, dark haired like his mother, thin still at the time, having not yet started to lift weights in the garage, something you only now realize might have had to do with his father. See brave Linda, who looks like a beautiful and young female version of Uncle Dave, which she did her best to rid herself of at some point in her twenties when she got a wholly unnecessary nose job and began dyeing her hair red. She is the one to challenge him, not Joan, not Tommy, certainly not you. Note your relief and surprise when Uncle Dave suddenly lets the whole thing go, drops Tommy’s arm and reaches quickly, automatically for his beer, and how you all eat in silence until, finally, Aunt Joan turns to you and asks if you’re looking forward to seeing Santa at the mall the following day.

9. No. That’s not it. You weren’t a Santa-visiting child then. You were older. You and Tommy and Linda were in your early teens. Instead of Santa, you would have gone on long aimless walks together with some of their friends and smoked cigarettes and shared a small bottle of pilfered peppermint schnapps, you always on the outside of the group, the interloper, unable to really talk to anyone except for Linda. Recall their Harrisburg idioms, the slang you struggled to make sense of. The inside jokes you were not privy to, because Tommy made it abundantly clear that bringing you along was an obligation and not something he would have preferred to do.

10. Take a moment to acknowledge your gratitude for Dr. Becky and the tools she has given you for addressing and processing your trauma. Recall the body shaming incident again, only now recall it without the shame. You did not deserve that. Let it go. See? See how much processing you’ve done already? Take another sip of the G&T.

11. Also acknowledge that, despite the processing and healing, your current level of distress is exacerbated by the realization that Tommy has surely inherited some of these traits from his father. Things like that are passed down, cycles perpetuated, etc. Dr. Becky insists that part of what we must do to achieve healthy personal growth is to identify and nullify negative patterns. Tommy is clearly the victim of very powerful negative patterns, as evidenced by the time when, as kids, he deliberately pushed you into a patch of nettles. Recall your mother holding a cold washcloth to your lower back.

12. Wander back to the photos. On the same wall is a shelf on which sits an award statuette engraved with Uncle Dave’s name. Realize there is a lot you didn’t know about him. We are, after all, complex animals. Wonder what you could do in your own life to one day be worthy of an award. Consider doing something for children. Or better yet: orphans. You yourself are an orphan, which strikes you as an odd thing to be at 37.

13. Turn around when someone clears their throat behind you. Discover that Tommy has snuck up on you, which you take as further proof of his dilapidated mental state. “Gary, what are you doing with Dad’s award?” he says. You’re surprised to see that you’re holding the award—a hunk of Lucite in the shape of two hands doing a handshake bearing the words Harrisburg Order of Civic Friendship, Dave K. Lowry, 1997. Even with Tommy standing there with an accusatory look on his face, take a moment to run your fingers over its delicate edges. “You know Dad loved that award,” he says, “so maybe don’t mess around and break it, huh?” This could be a humiliation technique, but he’s not entirely wrong. There are some clearly flimsy parts sticking out at the ends of the Lucite arms. They could snap off. “You think I need this today?” Tommy says, eyeing your G&T. He holds out his hand and you put the award in it. “The glass, Gary,” he says and hands back the statuette. “Back on the shelf, and watch the drinking, okay?”

14. Mentally replay one of Dr. Becky’s DVDs, the one in which she says that inner growth often results from placing oneself in unfamiliar surroundings and seeing how one gets on under the duress of not knowing anybody or even knowing where to go for a decent sandwich. Here you are in Harrisburg, which has grown unfamiliar over the many years of your absence, trying to glean positivity at a funeral. You’ve read that this is how boys become men in Africa. Not by traveling to Harrisburg, but rather by going off into the wilderness to fend for themselves and possibly entering into combat with a lion, and additionally without the convenience and security of their houses and families. And when they return to their houses post-wilderness, they are changed. Positive, Growing Change. Although more likely they live in huts.

15. Careful to avoid detection by Tommy, head to the rolling bar and accept Dom’s (?) offer of another G&T. Then, in need of some peace, sneak off to the pantry where instead of peace you discover Linda crying into a large sack of flour. Wonder briefly about appropriate levels of grief and about catharsis and the various ways in which we as damaged human animals express our many emotions. It’s been years since you’ve given any thought to Uncle Dave’s penchant for casual cruelty or whatever his specialty was, but being here now, supporting your family, you can feel in your bones that he has misused people in bad ways. Wonder if there’s a sense of relief in Linda’s tears. Could a human even discern that? Maybe one of those cancer-detecting dogs could. Gulp down the last of the G&T and pat her reassuringly on the shoulder. When you do this, she jumps like a frightened kitten and looks at you with huge red eyes. “Oh, Gary,” she says, her shock giving way to arms being thrown around your neck.

16. Take this embrace as a sign that the healing can begin. Linda must acknowledge the awfulness of the past in order to begin the rebuilding! Over her sobs, say, “That’s right, Linda. Let it out.” And boy, does she. Soon she’s practically having a seizure. Recall how Dr. Becky says that sometimes when our pain has been sublimated for too long an inner dam must first break before we can allow the river of our emotions to flow once again at a healthy rate. Tell her she’s not alone. Tell her you know all too well that her father was a monster.

17. Feel how, with this avowal of solidarity, her sobs lessen. Her river resumes its correct path! Feel proud that you’ve taken the first beautiful step of an important journey, together as family. She pulls away. “What did you just say?” she asks.

18. Say to her, “We can overcome our trauma!” Say to her, “Your dad can’t make you—or anyone—suffer anymore!”

19. Smile as she calls out for Tommy. Maybe you’ve misjudged your own cousin. Surely he’s suffered as well. Been victimized at great length and intensity, etc. He must be in need of some dam-breaking, too. Identify and nullify, is what you will tell him. This is where it begins! Tommy arrives in seconds.

20. Listen as Linda says, “Gary, tell Tommy what you just said to me.” Here’s your chance. You’ll do Mom proud in terms of familial supportiveness! Put a hand on each of their shoulders. Say to them, “I know how hard this is. The complex emotions, the years of trauma. But we can change this.” The looks they’re giving you? These are grateful looks. Say to them, “Whatever awful things your dad did, we are not hopeless! We can heal.”

21. Take note of Tommy’s confusion, as though conflicting sentiments are waging an important inner battle. Ask him, “He body shamed me, do you remember that?” Ask him, “Did he beat you?” Turn to Linda, knowing that no amount of hurt and damage is unrecoverable from, and ask her, “Did he…touch you?” Watch her eyes go glassy with tears. The healing starts here, is the message you are getting in huge neon letters even as Linda again erupts into sobs.

22. Wonder how you should react when Tommy says, “That’s it. Get the fuck out of here, Gary.” And before you realize it, he’s got you by the arm, painfully jostling you out of the pantry.

23. Protest as he drags you through the house, but do it quietly so as not to bring up family skeletons in front of strangers. But even so, everyone turns to watch this parade of misunderstanding, because that’s surely what this is. Experience genuine confusion when the buffet table gets knocked over. Look in the direction of the breaking China, and as you’re being pushed out the door, see Aunt Joan’s questioning expression. Resist the urge to struggle as Tommy hands you off to Dom, who gives you a weak smile as he escorts you down the driveway. Accept that he’s just trying to be the good guy here, but he doesn’t understand. He’s not family. Up on the porch, see Tommy with his arms around Linda and Aunt Joan who are both crying, clearly in the midst of catharsis, now framed by a bunch of moochers and gawkers.

24. Yell to them, “We need to address underlying traumas! We have to acknowledge these things in order to heal!” Dom, you’re almost certain it’s Dom, pushes you into the passenger seat of his Nissan. Accept that leaving is for the best. You’ll mend fences later, at a less fraught time. Tell Dom that you’d like to go to the Greyhound station.

25. Be surprised to find yourself, again and again, thusly on fire, despite your widely acknowledged talent for flammability.

26. Consider worrying about how Dom drives, because surely he’s driving too fast for the road conditions. You don’t know how safe a driver he is on a good day, let alone now, in this downpour. His instincts could be way off.

27. “Look,” he says, “it’s a rough time for everybody right now. You gotta let the family work through their grief without adding to it, is what I’m saying.”

28. Doing your best to conceal your fury, say to him, “The family? I am the family. I am facilitating! What about you, Dom? You’re a stranger picking up ice cubes with your fingers!”

29. Accept the rightness of your argument when he doesn’t respond, and instead turns on the defrost. Listen to the whooshing air. “It’s actually Don,” he says after a while.

30. Unbuckle your seatbelt when you arrive at the station. As you open the door, Don says, “Seems like you’re carrying around a lot of sadness, man. I hope you can work through that.”

31. The gall of this guy. The absolute nerve. Let this remark go, however, because what are you going to say? What could you even say to this kind of gross oversimplification? Who isn’t carrying around lots of stuff, Don? Exit the car and walk through the rain with your dignity intact.

32. In the station, watch as a man chides several children while attempting to wrangle an old woman displaying all the classic signs of dementia; watch a teenaged boy hiss racial slurs into his phone; watch an elderly couple carrying garbage bags and disintegrating suitcases held together by peeling duct tape. But regardless of this cavalcade of misery, the station is a relief. It’s times like this when you are thankful that you do your shopping almost exclusively with a Citizens Bank Mondo Mileage Card. Travel-related purchases are easily reimbursed with bonus miles, and, thanks to this, attending Uncle Dave’s funeral has cost you only $14 round trip. Change your reservation to the next available Pittsburgh-bound bus, another thing that’s a snap with Mondo Miles. Luckily, there’s a bus leaving in 40 minutes.

33. After retrieving your ticket, hold a free weekly newspaper over your head and step back into the rain to find a liquor store. Circumstances being as they are, you can justify a pint of bourbon. Allow only a small amount of guilt to creep in. There’s actually a whole DVD chapter devoted to stress-propelled intoxication (Disk 4, chapter 2: What Not to Do [Although We Desperately Want To]!). Your sense, however, is that Dr. Becky would understand the need for the occasional drink, given that what you’re aiming for is incremental progress. Going “cold turkey” would be a bit much to ask of anyone, despite Mom’s near constant assertions to the contrary. So allow yourself a drink when necessary and ask quietly for understanding. You can’t be too hard on yourself all the time, is the thing.

34. Back in the station, stealthily sip bourbon from the bottle, which is camouflaged in your backpack. Count the minutes until you’ll be at home and can process the day’s events in a productive manner. Listen to a garbled voice spit out departure information from an overhead speaker. Watch the other Pittsburgh-bound passengers make their way to the gate. Take your place at the end of the line. Sip bourbon from your backpack.

35. Notice, just as the line starts moving, a sudden and insistent discomfort in your bowels. Run, they instruct you with grave seriousness, evacuate with all possible haste.

36. Clutch your stomach as you rush past a row of urinals. Observe each one flushing in turn—a salute to all the times you have communed with toilets! Consider how urine is sterile when it leaves the body—the purest part of you escaping. Bright like liquid sun hitting the gleaming white porcelain and slowly dissolving the innocent pink of the urinal cake. Then the flush. Water rushing your urine seaward in subterranean rapids. Part of you joining the biggest thing in the whole world, the sea, and it is changed by you, not you by it.

37. Attempt not to dwell on the condition of the stall. Refuse to dwell. Think instead of the kind and thoughtful inclusion by the restroom designers of a dispenser full of hygienic seat covers. But then, before you can even make use of them, an announcement crackles through the speaker: Final boarding, 12:45 bus to Pittsburgh. Last call. Since you cannot fathom missing the bus, continue clenching and run.

38. Step carefully onto the bus. Shuffle down the aisle. Notice the other passengers looking at you, possibly sensing some inherent weakness of character for being the last person onboard, for being so borderline irresponsible. Go directly to the toilet but stop when the driver says sternly through the intercom that passengers must remain in their seats until the bus is moving. Find a seat and try to ignore the rumble of the engine. The driver lists all the stops you’ll be making, really taking his time with it, but then, mercifully, pulls out of the station. Get up and lurch down the aisle while the driver casts his evil eye at you in the mirror. Decide that you don’t care. Let his curses come for you! Lock yourself in the claustrophobic’s nightmare masquerading as a toilet. Breathe through your mouth as you drape the seat with hygienic covers and then drop your pants and sit. Briefly consider thanking God for small miracles such as this. Allow yourself a few sips of bourbon.

39. Wake to an insistent knocking at the door. You can’t deny that you are quite drunk. Slap the life back into your legs. Exit the bathroom to discover half a dozen surly passengers waiting. Consider apologizing but don’t. A man in a western shirt with a braided goatee sneers at you. Does he know what you’re going through? Of course not! This is another life lesson: Reserve your judgment! You do not know how hard others have it! Walk back to your seat. The duo of teenaged girls sitting across the aisle look at you and giggle. They have no idea what unpleasantness awaits them, and you don’t want to be the one to tell them of all the heartbreak and job loss and stretch marks in their futures even though you are feeling more than a little pained by their behavior. As you approach Pittsburgh, take solace in watching the landscape grow familiar and soothing, the aqueous quality of the light that is particular to the Steel City.

40. Let your thoughts turn to Tommy, Linda, and Aunt Joan. You have to believe they’ll eventually be able to acknowledge their pain. They’ll see that your actions, even if perhaps the timing could have been a bit better, were only in service of ripping the Band-Aid off to allow the healing to begin.

41. Transfer to a city bus that stops three blocks from your apartment. Ride with your forehead resting against the window and feel the grease of the last forehead to rest there, but accept that the soothing coolness of the windowpane is more important than any potential forehead bacteria. Downtown on a weekday afternoon is so awful you can hardly stand it and yet there are people all over the place, completely at ease, closing business deals or whatever, all without a single thought to the probably impending cataclysmic events in their lives. Or maybe they’re not worried about that. Maybe they’ve already found Positive, Growing Change. At a red light, watch a man kiss a woman on both cheeks as they meet crossing the street. Right in the middle of the crosswalk! It’s the most European thing you’ve ever seen.

42. Arrive at your apartment and acknowledge your gratitude that you have not, to your knowledge, been burglarized. Lock the door behind you, slide the deadbolt shut, and plop down into the comforting embrace of your sofa. Open your backpack for the bourbon and, along with the bottle, find Uncle Dave’s award. Become aware of the hot buzzing in your head, the grotesque cramping in your stomach: the hallmarks of an impending shame-spiral. This is not due to the guilt of having “stolen” a cherished family keepsake, but due to the embarrassment at being thought of by the family as someone who would steal a cherished family keepsake. Become sickened by the idea that you might be judged so unfairly. You can offer no explanation for the appearance of the award in your backpack—this alone should exonerate you! Accept the overwhelming need for a drink. The bourbon is all gone except for a doleful little swish. Drink it and hope for the best.

43. Dr. Becky says it’s good to have a support system in place for when we are handed lemons. Look at the clock. Almost 6:30pm, which is too late to call Gil Zwieback at the counseling center to ask for advice on alternate support strategies. You’ve called him at home before and he seemed genuinely surprised by it. But you told him his phone number was there on the internet as a matter of public record. He said that you should probably talk about boundaries.

44. Become aware of your growing anxiety. You need to find your center, reevaluate, and concentrate on how to return the award unnoticed and unblamed. Put on the Your Power to Heal! DVDs, starting right at the beginning—Disk 1: You Are Also Worthy of Love and, By the Way, Your Emotions Are Valid, Too. Notice your anxiety already beginning to ebb during the opening credits. Dr. Becky is a godsend. Feel a pang as she appears on screen. A pang of what? Comfort? Desire? Can it just be a non-specific pang? A slight but not unpleasant pain in your side.

45. Follow Dr. Becky’s guided meditation and gradually feel a renewed sense of calm. You will find a way to address the award. Even though at this very moment Tommy is surely impugning your character to anyone within earshot, even though your family is surely already referring to you as a petty thief, deepening their suspicion that you are the “black sheep,” you will find a way to fix this. Do the focused breathing exercises and a round of affirmations. With each wave washing over the rocks (the DVDs are filmed on an inspiring Hawaiian beach), feel your desire for calmness manifest itself. Repeat Disk 1’s mantras: I am alive in this moment! I am present! I will persevere! She speaks softly but confidently over the crashing waves, but not in a sexual way, although who can say what other people find arousing? Repeat aloud: I am here, and no one is any more deserving of happiness than me.

46. Meet Dr. Becky on the beach. The waves lap at your bare feet and together you intone mantras over the roar of the ocean, drowning out all the cataclysm and disharmony that the world holds in store for anyone. Then, just as the sun dips into the water: a swell of fiery Hawaiian drumming!

47. Wake up in the dark, the weight of the Lucite hands on your chest, the sunset replaced by the DVD player’s logo slowly floating across the screen, caroming from wall to wall. Note the discomfort in your head. Your phone chimes. Six voicemails from Tommy. In addition to the hangover, find that your right ear is completely stopped-up. This has happened before. Thanks to a mishap in the bathtub a few years ago, you have a perforated eardrum, and this, coupled with chronic sinus issues, sometimes leads to your ear becoming stopped-up, plunging you into temporary partial deafness. It’s maddening—the deafness, the loss of equilibrium, the pressure in your sinuses that feels like a leather strap being tightened. There’s also nothing you can do about it except take a handful of Mucinex, put a hot washcloth over your ear, and wait it out. But that can take hours to have any effect. Stand up a bit unevenly and pace the length of your apartment. Rap your knuckles along your upper jaw hoping to loosen the clog of fluid. You’ve been here before. Every time this happens you’re sure it’ll be permanent. Panic overtakes any rational part of you and even Dr. Becky’s mantras can feel useless.

48. Spin in circles in the middle of the living room. You don’t know why or how spinning ever became a coping mechanism, but when the sinus/ear thing happens it’s never long before you find yourself doing it. It must have helped on some unremembered occasion. Peeking over the top of your panic like it is a wall, think that if you just spin quickly enough the centrifugal force will eject a globule of mucus and you won’t end up being discovered deaf and dead of a panic attack, alone in your apartment.

49. If Dr. Becky has any plans for another DVD installment, which you sincerely hope she does, realize that she’d do well to address this intersection of emotional and physical discomfort. She could even include you as an expert on the subject. Return to the beach. She’ll say something like, “Friends, with me today is a very special guest. A man who is no stranger to suffering and in fact has met his own personal demons head on to come out the other side like a phoenix rising from the ashes of personal trauma!” And you will nod wisely along.

50. Say to the camera, “Trust me when I tell you that no matter how bad you have had it or are currently having it, I can empathize! Do you want to talk about negative life-changes coupled with physical ailments? Let us not even talk about that! Let us instead talk about our ability to surmount these challenges! Let us instead talk about how no amount of suffering is too great for us to overcome!”

51. Think about how you’d act if you were ever to meet Dr. Becky in person. Would her hair smell like you’ve imagined, like coconut? Her face is the very embodiment of inner calm and personal fulfillment. Consider how you’d thank her for her DVDs, acknowledging how helpful they’ve been for you. Although it’s not as if you were some basketcase slob before the DVDs. You were simply in need of some extra tools. You’ve been through a lot. Your mother’s death, for instance. Recall her in those final months. Mostly she was this zombie presence in the house, lying like a small bundle of sticks in her rented hospital bed, out of her senses with morphine. Recall the occasional lucid moments in which her eyes became unclouded and she was able to lament all the things she would never have the chance to do now, like visiting her favorite beach in Maine again, like the bird painting class she’d looked up online. Recall how you became thankful for the morphine because, at least, it dulled those regrets for her.

52. Remember going to Darlene’s apartment, who, even though you hadn’t seen her for years, was still kind enough to obtain marijuana for you, which you then baked into a batch of cookies and fed your mother tiny bites of. She could hardly swallow anymore because of the tumors, but smoking it would have been impossible. Recall how, after she choked down a few bites, nothing happened for a long time, but then just when you thought the marijuana would have no effect on her she asked to be taken for a drive. So you bundled her up in her heaviest coat, although by then you could have fit two of her in it, she was so small, and you half carried her to the car and drove. It didn’t matter where, she told you, she just wanted to look at the clouds. They were so interesting all of a sudden, she said.

53. Think back on how grateful you were later that night once she was asleep and how you called Darlene to thank her for the marijuana. But she couldn’t talk, she said, because her baby needed to be bathed.

54. Recall your rage at your mother’s pancreas. That bullshit little organ. Wonder if it’s even an organ. What does it do? How can something so seemingly inconsequential—does anyone aside from doctors even know what the fuck it does?—decimate a body like that? What goddamn right does it have?

55. Continue spinning, continue hoping to dislodge whatever is clogging your ear. As you gain speed, marvel at how the meager interior of your apartment is transformed into a wonderful pattern of horizontal stripes. The room blurs, close your eyes and keep going, gaining speed.

56. Hit the wall with your head and collapse. As you look around, confused, watch the room gradually right itself. You’ve knocked a photo off the wall. The glass is intact so you pick it up. It’s you as a little kid, Mom and Dad on either side, arms thrown around each other and you, too, in some approximation of a group hug. Look at yourself and wonder who this smiling little doofus even is.

57. Touch the right side of your forehead and locate a hot, tender bump. Your head is chirping like it’s alive with grasshoppers, and for a moment all you can think of is mid-summer and Darlene, and the time you went to that bed and breakfast in the Poconos. There were grasshoppers chirping everywhere at night, so loud you’d have to raise your voice to make yourself heard. But then you got used to the chirping, you got used to Darlene, to her lying on the four-poster waiting for you, and now here in your apartment the chirping fades as well and you hear only a dull noise like some piece of metal that’s been clanged and left to ring itself out. A distant, imperfect bell.

58. Recall Uncle Dave and Aunt Joan welcoming you into their home once, when Mom and Dad were fighting especially badly. They’re both smiling at you as Mom drops you off and without a word gets back into her old yellow Malibu to return to Pittsburgh where she will fight some more with Dad and then leave him at the end of the summer and then you and Dad will spend the fall alone together, him sitting often in brooding silence staring out the window, until Mom comes back to get you and you move into an apartment with her and then Dad eventually moves to Scranton. Wish that you’d had Dr. Becky back then.

59. Feel the inexplicable need to go outside. Maybe the nighttime air will let you work on positive solutions. Maybe being outside will give you the necessary space to process everything that happened at Uncle Dave’s funeral and the unpleasantness associated with trying to foster an environment conducive to healing. Maybe you’ll be able to address the accidental theft of the award and the shame surrounding that. Maybe the stopped-up ear too. Identify and nullify!

60. Marvel at Pittsburgh at night! Dark and humid and quiet. There’s no one on the street, not even raccoons. Feel grateful for the solitude. Walk unevenly, which is now partly due to the ear and partly due to the head konking. Notice that within a block the cool air is already working its magic! Keep walking. Feel the blood rushing around inside of you. Think: If walking is this beneficial, imagine what running will do!

61. Run. Soon there’s something happening. Your hearing isn’t back yet, but over the rush of blood in your head tell yourself that you can hear your footsteps. Tell yourself that you can hear the control boxes at each intersection clicking over to change the traffic lights as you pass. You haven’t run in years! It’s wonderful. Think back on other times you’ve suffered from the ear thing. Wish that you’d thought to run then. Watch as scraps of litter blow along the street seemingly under their own power. Look down Franklin Street and see the broken discs of light from streetlamps where they spill from the sidewalk onto the asphalt and wonder if this is all simply what God, in whatever personal way we each conceive of a higher power, has planned for you. Perhaps these trials are yours to endure and this suffering will eventually make you a better person; no more need for coping mechanisms or mantras. But until that day comes, if it comes, tell yourself that you’ll go on bearing your specific crosses with hopeful dignity. You will repeat your mantras and, when necessary, run. Your ear hasn’t drained yet, but it will. The pressure will lessen with a long triumphant squeal. You’ll spit the mucus, tinged with iron-tasting blood, victoriously into the sink and that marbled glob will slide down the white porcelain into the drain and be gone. Another part of you joining the water, rushing seaward, home. And likewise, at some future point your family issues will be resolved.

62. Notice Uncle Dave’s award in your hand.

63. As you run, holding the shaking hands, think about how maybe you could still return it unnoticed. Tommy’s voicemails might be unrelated. They might be his guilt manifesting itself at having treated you so unfairly. Maybe he’s been calling you over and over (six times!) to apologize. You could take the next bus back to Harrisburg, slip into the house, and put it back. Tommy probably hasn’t even noticed that it’s gone. Things are never beyond repair. Maybe you could all go for brunch!

64. Allow yourself to be buoyed by the sudden thought that despite the feeling of permanence in each individual moment, eventually things may change. The idea that things will never change is something that’s been ingrained in us since birth. You know this for a sad fact, just like you know there are hands at the ends of your arms—you’re not saying that will never change, who knows? Your hands could get chopped off tomorrow! You’re just using it as a point of reference. But through lots of hard work utilizing Dr. Becky’s system you’ve learned that things frequently do change, although more often than not in ways we don’t like. For one, you’re not getting any younger. Kid yourself and say, Your hair’s not thinning up top! No one you’ve ever loved has left or died! These are changes you could do without. Ask God to let you keep your hands, let them stay, let them not leave you at an inopportune time!

65. Look about 100 yards ahead of you—someone, a young woman, is standing on an overpass looking down onto the train tracks. Could she also be suffering unjustly from some manner of panic or injury? But even if so, what can you do? Interact somehow? Place a sympathetic hand on a stranger’s shoulder? That didn’t even work so hot with cousin Linda earlier! But still, slow down and walk cautiously her way. Sharing even just a small moment of human interaction might help during whatever personal life issue she’s undoubtedly facing. Maybe just a quick nod? As in: Even though we are both in this moment alone, in a different but equally valid sense we are also not.

66. Become struck, the closer you get, by this woman’s resemblance to Dr. Becky. It’s uncanny. Reconsider approaching. Decide to just watch for a moment from a discreet distance because, after all, despite any desire for commiseration you recognize that sometimes the best thing is simply to be left alone with your thoughts. She might even lash out, misunderstanding your intentions, irascible and confused as God knows we all have every right to be. She really does bear Dr. Becky a striking resemblance despite how you’ve never once seen Dr. Becky standing on an overpass at night. But even lacking the proper context this is somehow comforting. You’re not thinking of the stopped-up ear or Tommy’s yelling or even your guilt about the award. You’re simply aware of your heartbeat and breathing and how both are now slow and even. This isn’t either how you would have imagined Dr. Becky being dressed in her private, off-camera life. You’d have thought she’d be wearing perhaps a skirt and blazer. A power suit. Or is it called a pantsuit now? The woman on the overpass has on frayed jeans and a sweatshirt that’s several sizes too big.

67. The thing is, the look on her face is just awful. Your heart goes out to her. Despite whatever personal shortcomings you’re plagued with, or even perhaps because of these shortcomings, you can recognize suffering in others and feel that someone should help alleviate that suffering if the opportunity presents itself. Realize that in this moment you want nothing more than to be the cause of this woman feeling any amount of, you guess, less aloneness. If you can do something to affect any kind of Positive, Growing Change for her, it would also surely lessen your own burdens. That must be how Dr. Becky feels. Approach her with a deep sense of calm and purpose, pushing all your feelings of reluctance down into a tiny ball that you will address later at an appropriate time.

68. Watch as she cranes her head to look further down the tracks, perhaps even hoping to alight on some small background detail that will provide her with solace. A bird taking flight, a cloud teased into a pleasing shape. But instead of that you see what she’s actually looking at. An approaching train. As it gets closer she swings a leg over the overpass’s low wall.

69. Overcoming whatever social constraints exist in cases such as this, shout at her: “Hey!” She looks at you with you don’t know what in her eyes, but is maybe fear? Drop into a sprint as she looks down at the tracks again. Shout: “Wait!”

70. She’s got both legs out over the tracks now, the laces of her dirty white sneakers dangling untied. With maybe 30 yards between you still, you can finally see her face clearly. She’s young but her forehead is crisscrossed with lines. Her lips are pale and thin. Her eyes glow dully under stringy bangs. Realize that she looks nothing like Dr. Becky. She looks like Dr. Becky post-hunger strike. Dr. Becky’s cousin on her third round of chemo. Yell, “No, wait!” She looks up again. Yell, “Hey, no!”