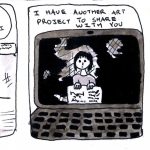

I have been researching computer-generated literature for many years now. Over the past few months, I experimented with reduction to dot-to-dot as a method of generating erasure poetry. It started with restrictions with Hershey text but with these works I have been able to make a more complex, more emotionally connecting style.

Category: Literary Features

To All Whom It May Concern

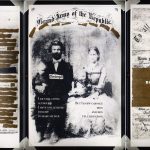

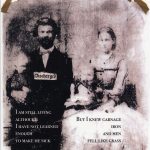

“To All Whom It May Concern” is a triptych of documents from the Civil War that includes: 1. An erasure of the first page of a four-page letter written by Lyman Jones to his parents while he was held a prisoner of war in 1863; 2. A later photo of him with wife and two children; 3. His discharge orders, over which a second erasure is pasted—words cut from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” as published in his 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass.

Two Erasures

In a few months another baby will get to the internet

Still sore and broken

after its husband did wrong

betrayed by the woman

the world.

I was secretly hoping

that his eggs made a litter

because the meltdown didn’t happen

there is new news

that years

will soon spit

newborn shit on their hands

To cover that it’s a ‘man’s world’

I’m certain, therefore delighted.

We are expecting a November

named yesterday.

From his yes and into his sound

like the name of a California town

Somebody spiked the table

with fertility.

Either knocked up or out

and now

that grumbling might be Jesse James

It might be America

baking in her.

“In a few months another baby will get to the internet” is an erasure from a Dlisted.com blog post on 7/9/14 titled “In A Few Months Another Baby Will Get To Call Robert Downey Jr. ‘Daddy.’”

We choose to smile in the face

1.

We choose. We choose to look at time.

We choose fives. We choose zig, else zag.

We choose a lot of things, but,

choose us.

Happiness is enough.

We choose to live—

purpose.

Your scent, your style: try these fragrances.

Secret escape.

Everything is better with purpose.

Find out why.

An empty box is filled with possibilities

(find the bottom).

This box is full.

100%.

Don’t throw it away, it’s too pretty:

a light manufactured by Saint Louis,

owned by

société de produits

or used with permission in a dry place in the USA.

2.

Go.

With absolutely everything.

3.

Purpose in 3 simple steps:

Step 1.

Step 2: pour purpose in a box. Refresh.

Step 3: Unwind. Throw some shoes.

You want to worry.

Trust us. You’ll love it.

“We choose to smile in the face” is an erasure from the text on the back of Purina Purpose Clumping Cat Litter 23-pound box.

Plum Trees, Astray, Verso, A Little Croquis, and Snow Still

Wory Gardn

Seduction

November Nineteenth [On Erasure]

This erasure is from Donald Culross Peattie’s An Almanac for Moderns, a book of daily essays on the natural world written in the Midwest and published in 1935. Moore uses the book as part of a daily erasure practice, erasing the correspondent day and seeking to radically transform Peattie’s meditations, dramatically shifting the topic and focus of the original entries.

Peattie, Donald Culross. An Almanac for Moderns. Editions for the Armed Services, 1935.

The Mueller Report, Vol. 2, Page 147 Fairy Tale

Selections from VIOLETS

Milk Glass Serenade

I cannot see what flowers are at my feet, nor you,

not yet born, your eyes and body of milk glass.

Here, let me

tell you an old saw:

A county of men filled a valley with lake, shaped

like an urn. They bestowed on it

a spillway, baptized The Glory Hole.

The surprising dark. A tunnel to the very center.

The oldest say you can see the steeple

in a dry year, impaling serous sienna.

For months, these men excised canned goods, locomotives,

the dead. Every Beware of Dog, gazebo, five-and-dime—

but left all ambitious underwater elms, which above-surface

had dropped off from Dutch elm disease.

Please become born, baby,

so I have someone to serenade. In kindness,

I’ll lie: lullabies moved from the valley,

with the children to whom they belonged.

When you lose your fresh pearl teeth

I’ll draw parallels to caverns in the hills.

And should you be unlucky enough to be beautiful,

I will tell you of the trees in this novel lake:

the forced dance, the bend

and break, trunks as carefully preserved as crow’s feet

in a wax museum grin. Trapped in line so thin, so dear

you cannot see it: the mobile of refuse, waving hello baby.

bluebeard’s servants

I ran out on the sidewalk

under the broken streetlight

dry leaves chuffing overhead

like someone rubbing their palms in a black room

a muffled radio from a parked car

blue drool dribbling from its tailpipe

the green needle of the radio dial

like a knife’s edge in a dream

I heard you calling my name

like I was in trouble

like you were right there beside me

with an unwashed cup in your hand

but I knew you weren’t outside

I watched you leave the yard

barefoot in your robe of fireflies

I knew the house was empty

the lukewarm sleeping flank of the drier

the dishwasher’s matted pelt

the long black velvet box of the hall

blood on the keys

I was always the child who had to look

who went in the study with the torn chairs and stuffed birds

who upended the trinket box and found your fob

my breath rattling in my throat like bones shaking in a dice cup

I saw the hot coil a carful of blue smoke

why didn’t the driver help me

Mother shrugged as you led me away

to the inevitable chamber

where dead girls moulder in velvet gowns

locked in like wives

The Mother, the Bee, the River’s Edge: A Story from The Kalevala

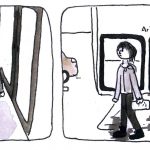

This comic strip is an adaptation of part of the first Lemminkäinen cycle in the Finnish epic, The Kalevala. The Kalevala is an adaptation of the oral folklore of Karelia and Finland written by Elias Lönnrot and is considered a major cornerstone of Finnish identity and culture. I started reading The Kalevala to get a better context for some of the metal music I listened to and found myself drawn to the women in these narratives. To me, they were as interesting (if not more so) than the male heroes. Lemminkäinen’s mother, in particular, is my favorite character, despite not being given a name herself. In this comic, I hoped to capture her own heroic journey and how her son’s happy ending did not necessarily lead to her own.

I Live in Grandma’s Kitchen

I live in Grandma’s kitchen. The walls are the blue and white she painted them a few years ago. The cabinets have the tiny white knobs I reached for when I learned to walk. Through the window above the deep sink, tonight’s overcast sky creeps its way over the setting sun and into the chilled gray room.

While pouring a bag of beans in a pot to boil, and before I grab a jalapeno and cut an onion in half so that I’m just on the verge of tears, I hear Grandma yell from the living room.

Don’t be dumb, you’re making them wrong. Rinse the beans before you boil.

I stop what I’m doing and rinse them or else she’ll make me keep doing this until I do it the right way.

—

I’m washing the dishes. They’re all perfectly matching, off-white and no chip in sight, except for one plate. It’s brown, bigger than all the rest, and has this sketch of a cottage in winter on the face of it. It’s the only one she will eat off of. It’s covered in the remnants of food that she didn’t end up finishing off with her tortilla. The little cottage’s windows are coated in the marks of beans refried with Manteca. As I rinse off the plate, with the rough side of the small yellow and green sponge, I see the windows open and the snow-covered photo pop amongst the sea of off-white in the silver sink. The dishwasher is full. I bully around the bowls, shift the silverware, and arrange the cups so that I can fit this one last dish in before I pour the detergent and finish off the sink with my pruned fingertips. Scouring for something sweet after dinner, I hear her shout from the pantry.

That’s not how you’re supposed to wash dishes. If you break a plate or my washer, you’re going to pay for it.

I pull out her dish and wash it by hand. It is her favorite.

—

I fill a bucket with Clorox. I feel the bleach burning the insides of my nose as it swims with the tiny bit of hot water and soap. I push all the kitchen chairs into another room, pick up the mat from the sterile grey linoleum and sweep away the red-brown pine needles I tracked in after school with my boots. The mop slushes around in the suds as it prepares to douse the floors. I roll up my jeans to avoid the splash the little gray braids will make when they hit the floor. I will feel the warm water underneath my now bare feet and move my way from one corner of the kitchen where the cabinets meet the wall, all the way to the tiny forgotten space where the refrigerator just barely misses touching the ivory-colored baseboard. From the TV room, I hear the sounds of her Mexican soaps go silent.

Stop being lazy. Just scrub the floors on your hands and knees.

I listen because I’m tired.

—

I turn off all the overhead kitchen lights but keep the dim stove-top light on. I rest. The kitchen table is small, tan, and the chairs have no cushions on them. The hard oak starts to hurt if you sit for too long, but it feels better than standing does right now. I sigh and pitter my fingers, reaching for an orange in a basket to squeeze and play with so that I don’t need to think anymore. The hall out of the kitchen is dark, but I can make her figure out, shuffling to bed, dragging her slippers on the dark, plush carpet. With her hands stuffed warmly in her robe, ready for bed, she says.

It was all delicious. Good job, Mijo.

I smile and tell her I love her because… well, because.

—

Now I’m sitting here, and I finally have nothing to do. The food is all done, the dishes are dry, and the floor is sparkling in the tiny bit of light that’s left in the room. I ask her what to do now, but there’s no response because hospice came and took back their oxygen machine, the shelves of her medicine cabinet are free of pills, and a bottle of Chanel is sitting on her vanity unmoved for four years now. Now all I do is live here in her kitchen and wait for her to yell again.

The Strangers

The day of his daughter’s arrival, Daniel cut back the Marilyn Monroes. He’d pruned them every January for the past ten years. The roses were a true victory—he’d been called a gambling man by a horticulturist who warned Daniel he wouldn’t be able to keep Marilyn Monroes alive. They were too finicky, they required a frost in the winter and the temperature didn’t drop low enough in Tampa. But Daniel knew he could keep any plant alive.

Daniel wasn’t sure why Hayley was coming home. Hayley’s email had said: “I want to say goodbye to the house.” Why? How was it possible to tell a house goodbye? If his wife, Olivia, had still been alive, she would’ve explained it.

The house was packed, and the movers would be there the following week. Daniel had already shipped most of Hayley’s belongings to Los Angeles. Daniel knew never to throw away anything Hayley owned. When she was a little girl, Daniel had made the mistake of throwing away a headless Barbie he found by the pool, and Hayley grieved the loss of the doll for weeks. Olivia had been livid. She’d called him heartless and ordered him to never touch his daughter’s possessions again. For Daniel, objects had little history or future. He couldn’t understand why Hayley and his wife had gotten so upset. But Daniel remembered Barbie when it came time to pack up Hayley’s things. He tossed everything from her room into boxes without examination. Just a few packages remained to be sent to her in California.

He finished tidying the roses. There was still enough time for a Gatorade and a shower before Hayley arrived. He’d just stepped into his bedroom when there was a loud knock at the door. He found his daughter on his steps. It was the first time she’d been home since his wife’s death a year back. She smiled up at him.

“Hello, Daddy,” she said, shyly.

Despite the fact he knew nothing about her—favorite color, movie, food—still, his chest grew warm at her smile. The same smile she’d had all her life. He was shocked by how much he wanted to pull her to him. He remembered the satiny feel of her skin when she was an infant, the way she’d kicked her feet when he said her name.

“I got on an earlier flight,” she said. “I tried to call you.”

Damn iPhone. Since his retirement, he forgot to even turn it on.

“It’s so weird here,” Hayley said, her voice an echo in the cavernous dining room. Olivia had wanted the drafty old house. Daniel couldn’t wait to sell it.

“Do you really want to move?” Hayley asked, trailing a finger across the top of the buffet, the only piece of furniture he was keeping because it had been his grandmother’s. When she looked at him again, the smile from the doorway had disappeared. There were dark circles under her eyes, creases on her forehead. How old would she be now? He did the math. Born the year he’d made partner. She’d be forty in June. There were small patches of grey at her temples, her hair the color of chestnuts now instead of purple.

“I don’t need the space now that it’s just me,” he said.

“It’s so weird without Mom,” she said. “Isn’t it weird?”

It had been. For a little while. No rattle of Olivia’s old Mercedes. No smell of lemon in the morning. Now it felt normal. And good. Of course, he couldn’t say he didn’t miss Hayley’s mother, that he realized at sixty-seven he’d never been in love, and probably never would be.

He said, “Yes. Very weird.”

“I’d like to lie down,” she said. “Long flight.”

He’d left her twin bed in her room, and he led her there.

“I’ll be up in a few hours,” she said.

—

He ate at the deli for most meals now and his cabinets and fridge were bare. While Hayley slept, Daniel went to the grocery store and stocked up on all the things Olivia kept around: Stouffer’s frozen lasagna, bananas, whole wheat bread, butter, coffee. He remembered Hayley eating a cereal called Lucky Charms, so he bought a couple of boxes, happy that he remembered one thing about his daughter.

At just after seven that evening, Daniel knocked on her door. He’d heated up a lasagna, and it was getting cold. Hayley didn’t answer and, when he poked his head in the room, she said she needed to keep sleeping, that she’d had a “rough few weeks.” Should he ask her if anything was wrong? Was sleeping a bad sign?

On one of her last days in the hospital, Olivia grabbed him by the wrist and pulled him to her. So close he could see the red veins intersecting the whites of her eyes. This was the closest they’d been in many years.

“Promise you’ll talk to Hayley. She’s in a bad way.”

Daniel hadn’t been able to tell she was in a bad way. In fact, he hadn’t seen her looking so good in years. No purple hair, no bitten fingernails. The way she looked, it was hard to believe she was mentally ill, though Daniel wrote a check for $2400 every month to pay for her therapy.

When had his daughter become bipolar? It made his jaw clench to remember the promise Hayley had possessed—acting lessons, school plays, her declarations that she wanted to be the next Nicole Kidman. And she’d been so pleasant—squealing with laughter when he chased her in the pool, making up dances, using the cabana as her stage.

Since Olivia’s death, Hayley had called once a month, always on a Sunday night. They talked about rain. The lack of it in Los Angeles, so much in Tampa. If Olivia were around, she’d ask Hayley questions: Are you taking your meds? Going to bed at a reasonable hour? Working? But she had the right to ask. Daniel didn’t ask questions. What would he do if Hayley gave him answers he didn’t understand? Olivia and Hayley had their own secret language. Olivia bought a ‘best friends’ necklace and gave Hayley the ‘best’ half for her tenth birthday. The one time Daniel wondered if Hayley should have friends her own age, Olivia’s eyes filled with tears.

“My daughter is here for me. Which is more than I can say for you. You’re a stranger to us.”

No, Daniel would let Hayley sleep. He would leave her alone.

—

Just after eleven the next morning, Daniel heard the click of her doorknob. He was at the sink, rinsing a bowl when she padded into the kitchen. Bare feet, wearing a faded blue T-shirt and a pair of jeans. Her hair stuck out in a million directions. She looked the way she had in high school, after a night dancing, her hair reeking of smoke, making him wonder why he was spending thirty thousand a year on private school when she partied with the public schoolers and brought home Cs.

They said “good morning,” and he gestured to the box of cereal on the table.

“Your favorite, right?”

She smiled. “I don’t eat sugar anymore.”

Hayley grabbed a bottle of water from the counter and picked up a banana from the bowl. He waited for her to say something else. She didn’t. She left the room and, a few minutes later, he looked into the backyard to find her sitting beside the drained pool, her legs pulled up against her chest. The half-eaten banana was by her side. Her face was turned away. Was she saying goodbye to the pool?

After a few minutes, Hayley stood and went over to the steps. She walked into the empty concrete basin. She walked to the center and then stared up at the sky. Daniel craned his neck and looked up, too. Seagulls, a whole flock of them, flew in a V shape across the sky. A memory: feeding bread to the seagulls with Hayley when Hayley was a child. Hayley loved to chase the birds, and he had laughed and encouraged her to run faster. There had been good times. A few of them. Daniel considered walking out to the pool, bringing the loaf of bread with him. But Hayley might want to be alone. She might’ve come home for the peace she never got when his wife was around.

When Hayley came home for Christmas, Olivia made sure they had a packed calendar: ringing the bell for the Salvation Army outside of Publix, a carol sing-a-long at the nursing home.

“The worst thing she can have is quiet,” Olivia always explained. “I must keep her busy so she doesn’t focus on her sadness.”

But what if this wasn’t true? What if peace was exactly what Hayley needed? Daniel had been to Los Angeles once, and the traffic and smog had been as much of a shock as the coffee shop where Hayley worked, a den of tattooed and pierced people who huddled over laptops all day. Didn’t people in LA work? Why weren’t they at offices?

A few minutes later Hayley came in the house. He walked to her room. She sat on her twin bed, her back to him. He thought he saw her shoulders shaking.

“The new people are going to fill the pool in,” he said. “I had to drain it.”

“You never used it anyway,” Hayley said. “Mom and I were the only ones who ever went in.”

The cold tone of her voice was a shock. Better to give her space. Daniel shut the door.

Hayley didn’t come out again until dinner. He heated up another lasagna, and they ate it on paper plates. The only sound was when he blew on the noodles. After they finished, he asked her if she’d like to go for banana splits, a peace offering since she’d sounded angry about the pool.

“No sugar,” she said, eyes glued to her plate. “Remember?”

She picked up her iPhone and began typing, probably a text about what an idiot he was. Daniel cleared the table.

—

The next day Hayley sat out by the pool again. For hours. When it rained, she sat under the awning. He thought he saw her crying, but he couldn’t be sure. He wished his roses were still blooming. He could’ve shown her each one. She’d liked the garden a long time ago. She’d helped him add just enough aluminum sulfate to the soil to turn the hydrangeas blue. Seagulls, ice cream, flowers. The memories served as proof there’d been times when he knew things about Hayley. If only he’d tried harder, they could’ve been closer. But when Olivia was alive, it was like she and Hayley were the only people in the house. His presence was more like a shadow, lurking, ready to be dismissed, a stranger indeed.

Daniel took a nap and woke just before dinnertime. Hayley wasn’t in the backyard and she wasn’t in the kitchen. The door to her room was closed. He heard talking. He walked past, not wanting to disturb her, not wanting to eavesdrop. But what if something was really wrong with his daughter? What if her trip home was a cry for help? Was he being too dramatic?

He tiptoed back down the hall and pressed his ear against Hayley’s door. Murmuring.

He couldn’t make out words. But then: “I burned all those bridges,” Hayley said, shrill enough that he could make out each word. “I have nothing to go back to in California.” A cry. A moan.

Daniel gritted his teeth. He retreated into the darkness of the hallway, to his bedroom. He didn’t sleep for hours. He kept hearing his daughter’s words. “I have nothing to go back to in California,” she’d said. What did that mean? Had someone broken her heart? Had she lost her job? Who was on the other end of the call? He wished he could contact that person and get the story. Asking Hayley about it felt impossible.

He pictured her apartment in Los Angeles, the one time he’d been. The cactus in the windowsill. She explained it bloomed at Christmas. He’d taken her to the local nursery and bought her more cacti. “They don’t need much attention,” she’d explained. “I can always keep them alive.”

He’d thought that was weird then, another way they were different, another way he didn’t understand his daughter. Daniel loved that his roses needed him. They depended on him for water and food. They flourished under his care. Hayley and Olivia hadn’t flourished under his care. Olivia told him no amount of money could ever make up for the fact that he never laughed at her jokes, that he didn’t appreciate her thoughtfulness.

One Valentine’s Day she bought candy apples etched with hearts for him to bring to the office. Whoever heard of a grown man, the head of a law firm, bringing in candy apples for his employees, the same employees who were supposed to be terrified of asking him for time off at Christmas? He said he wouldn’t bring them in, and, one by one, over the next few weeks, Olivia ate the apples, crunching loudly, glaring at him.

Olivia wasn’t thoughtful. She wasn’t kind. But maybe she was right about their daughter. Maybe Hayley was in a bad way. But what could he do?

—

Sometimes, when clients were in town from far away, he took them to Palm Valley Fish Camp because the restaurant was famous for its fried shrimp. Would Hayley like fried shrimp?

He knocked on her door the next morning and, when she opened it, he suggested the dinner nervously. He expected by her swollen eyes that she would say no. But to his surprise, her face lit up the way it had when she saw him the night she arrived.

They decided on seven, and twenty minutes before she walked down the hallway wearing a cherry red dress with a puffy skirt and shiny black high heels. An outfit too fancy for Palm Valley Fish Camp, which was out by the marsh, and a place where the staff looked the other way if you smoked on the porch. Daniel always bought cigars for clients.

“Mom bought this for me to wear to prom, but I didn’t go. I chickened out. I never got a chance to wear it. Do I look okay?”

The dress was too big—the sleeves drooped off her shoulders and the bodice gaped at the bust and waist. How was she so much smaller at forty than at fifteen? She wore too much red lipstick—there were smudges below her mouth. The white powder on her face made her look like a ghost, reminding him of Olivia in her coffin. He wanted to tell Hayley to change. He didn’t like being embarrassed. But he forced himself to smile. “You look nice,” he said. Then he opened the door, and she followed him outside.

—

Daniel had forgotten it was Friday, and they had to wait a long time for a parking spot. Hayley hummed beside him, tapping her fingertips on her knees. He clutched the steering wheel, wondering if he’d made a mistake by inviting his daughter to dinner. But Olivia’s words reverberated in his head. “Promise me you’ll talk to Hayley. She’s in a bad way.”

—

They had to put their name on a long list and there was nowhere to sit to wait. They stood by the porch, where the air smelled like smoke and beer. Mosquitoes hummed in Daniel’s ears and he smacked the bugs away. Hayley kept curling a lock of hair around her finger, letting it go, and doing it again, a habit from her teen years. Daniel could feel the stares of the other patrons when they noticed Hayley’s dress. He kept a smile on his face, praying no one would comment. It wasn’t likely he would see anyone he worked with at the restaurant. They frequented the places in town or the club, where hush puppies weren’t an option.

Finally, their name was called, and they struggled through the knot of people to the hostess stand.

A girl in jean shorts smacking gum led them to a table in the middle of the restaurant, beside a table of guys wearing baseball caps. Daniel felt their eyes on them, and he glared at the biggest one, a burly guy in a Gators sweatshirt. Hayley said she needed to use the bathroom as soon as the hostess set their menus on the table.

It was so loud that conversation wouldn’t be possible. Daniel was grateful for this because his daughter was acting so strangely and he didn’t know how to find out why. Seeing Hayley twirl her hair brought back bad memories of sitting across from her at the dinner table. A typical night: Olivia chattered about the candlesticks she’d just bought from QVC while their daughter twirled her hair and didn’t say a word.

Then there were all the absences in high school. Olivia made excuses. “She’s not like the other girls. She’s sensitive. I can’t make her go when she’s sad.” But why was Hayley sad? He’d never understood. She had everything: diamond stud earrings that matched Olivia’s, an Audi TT when she turned sixteen. But more than material things. Daniel had given his daughter promise. Possibilities. The perfect start to a perfect life. Much more than he ever had, growing up in rural Alabama with a single mother who could barely scrape together enough money to put tuna fish on the table.

Hayley could’ve gone to any college in the country if she’d just kept her grades up. But she hadn’t. The only college that accepted her was a tiny one in North Carolina, which she returned from on holidays eager to read them poems she’d written. He remembered one in particular—she said her heart had been attacked by tigers and there were teeth marks in the aorta. The poem was titled: “Mother.”

Olivia had started crying when Hayley finished. Daniel’s first impulse was to comfort his wife, but she’d jumped to her feet, clapping her hands. She called Hayley a genius, framed the poem and hung it on the bathroom wall. It looked at him while he brushed his teeth. “She hunts me nightly. She never wants to let me go.” Hayley’s poem seemed to be a negative reflection on his wife. So why did Olivia like it so much? Daniel couldn’t fault his daughter for her feelings—after all he would’ve liked to write mean poems about his wife, too. Daniel didn’t understand poems. And he knew then he would never understand his wife and daughter. He’d always be on the outside, walking by the den where they huddled on the sofa, sharing a bowl of caramel popcorn.

Hayley returned to the table, her lips redder, her face paler. She sat down and the waitress appeared, barely glancing at them, scrawling their orders down on a pad. Fried shrimp for both of them. Hayley wanted a glass of white wine. He wanted a scotch and soda.

The drinks didn’t take long and thankfully, the food didn’t, either. While they ate, Hayley twirled her hair and stared past him or studied her phone. He played with the dial on his Rolex, watching the time creep past.

When the waitress passed by to ask if they wanted key lime pie, Daniel handed her his American Express.

He met his daughter’s eyes across the table, and she smiled. She seemed to be on the verge of saying something, but then her smile disappeared and she stared at the half-eaten coleslaw on her plate.

“Still making cappuccinos?” he asked, searching for something to say. And then to his horror, Hayley began to cry. So, she had lost her job again. One second she was smiling and now her shoulders shook, quiet sobs wracking her body. Daniel remembered Olivia’s words again: “She’s in a bad way.” What should he do? He thought about client dinners, but no client had ever cried before.

Eyes on them. The men at the table nearby. Theirs was not the kind of community where you had a breakdown over coleslaw. “The land of the raised pinky” is what he’d told his wife once and she said: “We’re lucky to live somewhere so beautiful. Don’t complain.” Daniel had to get them out of the restaurant. The waitress returned—thank God—he signed the bill and grabbed his daughter’s arm.

He was grateful to be outside again. It meant the night was almost over. He breathed in the chilly air and thought of his roses. The cold would do them good. He hoped the person who bought his house would care for them the way he had. He should probably pass along his tricks: eggshells and tea bags in the soil, olive oil rubbed onto the leaves.

They were almost to the car when Hayley’s name was called. Oh no. Who could it be? Had someone seen her crying? The caller was a pregnant blonde woman in a floral dress.

“I thought that was you,” she said to Hayley, whose eyes were wet and frightened. “This your father?”

She stuck out her hand, and Daniel shook it and introduced himself.

“Elizabeth,” the woman said. “Hayley and I went to high school together.”

She told them she practiced obstetrics at Baptist Medical, that she was on her way to the hospital because one of her mothers was going into delivery early, much to her husband’s dismay since they’d been celebrating his birthday.

“My drunk husband can’t drive me to the hospital, and with my belly I can’t fit behind the steering wheel—could you give me a ride to the hospital? It’s less than a mile away,” Elizabeth asked.

This was the last thing Daniel wanted to do. He needed to get Hayley home, rescue them from the awkwardness of the night. Who was this Elizabeth? Couldn’t she call a cab? He could feel his daughter’s eyes on him.

“Okay,” he said.

Hayley went back to twirling her hair. She walked behind them. Elizabeth got into the front seat. When he pulled out of the lot, Elizabeth looked over her shoulder and smiled at Hayley.

“What are you doing these days?”

Daniel glanced in the rearview mirror. Was Hayley crying again? He didn’t want her to answer. She was a middle-aged woman who’d been hospitalized for bipolar disorder following a suicide attempt. This Elizabeth—she was the kind of woman Daniel had imagined Hayley would turn out to be. A doctor, pregnant, happily married. Assertive enough to ask an old schoolmate for a ride.

“I’m so proud of my daughter,” Daniel said, the lie falling out of his mouth so fast he couldn’t keep up. “She’s a brilliant writer. A poet. She lives in Los Angeles now, and I don’t see her enough.”

How had he come up with this so quickly? Five minutes ago, he’d been unable to think of a single word to say to his daughter, and now he was expertly lying to a total stranger. Maybe it was all those years convincing juries. He didn’t know but he felt proud of himself for jumping to Hayley’s rescue. He’d saved them both from embarrassment.

Elizabeth snapped her fingers. “I remember,” she said slowly. “We were essay partners in American Literature. Your papers were always the best.”

Hayley stopped chewing her cheek. “Really?” she asked.

“Oh yeah,” Elizabeth said. “I’m not surprised you’re a writer now.”

“I wrote a book,” Hayley said proudly. She opened up her purse and pulled out a worn copy. She passed it to Elizabeth. Daniel had never read his daughter’s book. He’d been too freaked out by the title, which had been the name of a song he wrote in college for a class. The only time he’d ever done something creative. He had no idea how Hayley got her hands on the song—he’d assumed it had ended up in the trash, like all of his college papers.

“Broken Nightingale,” Elizabeth said, staring down at the cover. “That sounds good.”

“Thank you,” Hayley said.

Elizabeth handed the book back and gave Hayley her business card. She suggested they have lunch the next time Hayley was in town.

“This is my last trip here,” she said. “My father’s moving to Jacksonville.”

“Shame,” Elizabeth said and then: “You look great.”

Hayley’s eyes grew wide. Daniel turned into the hospital parking lot and drove to the entrance. Elizabeth thanked him for the ride, and they all said goodbye. Daniel was certain now that the sadness inside of him was written all over his face, and he clenched his jaw as hard as he could. When Elizabeth got out, Hayley didn’t take her place in the front seat. They were quiet on the ride home.

When he pulled into the driveway, Hayley said, “I’ll be out of your hair in the morning. I booked an early flight.”

She was leaving? But she said she had nothing to go back to? She’d bawled at dinner. For the first time Daniel missed Olivia. She’d do something, even if it was the wrong thing.

They went into the house. Hayley went to her room. Daniel stood in the kitchen, staring out at the dark backyard.

—

Daniel got out of bed just as the light in his room turned pink. He went to Hayley’s room. He wanted to look at his daughter one more time before she left. She slept on her side, the covers down by her ankles. She’d slept like that as a little girl. Now her hair was short, but she looked just as peaceful. He wished she could know that peace, that her brain wasn’t so mixed up, that she didn’t get sad enough to want to die. Maybe her brain would’ve been different if he’d been a different father. If Olivia hadn’t been her best friend.

Hayley stirred. She opened her eyes.

“Daddy,” she said hoarsely.

Daniel’s heart pounded. He might never see his daughter again. She’d have no reason to come home now that there was no home to return to. She wouldn’t travel all the way back to Florida just to see him. The yard was beautiful in the morning. Maybe she’d like to see it one last time.

“Come outside,” he said.

She rubbed her eyes and sat up. She followed him, in bare feet, in her old T shirt and boxers, to the backyard. Now the sun was higher. Dew sparkled on the grass, made the tips of the blades look like diamonds.

Hayley turned to him, tears in her eyes. Should he hug her? Maybe she didn’t want to be touched. He tried to choose a word, any word, but his mind had gone blank like it always did with his daughter.

“I’ll have a balcony at the condo,” he said. His voice sounded strange to him, far away. “Would you help me pick out plants for it? A cactus maybe?” He wasn’t sure what he was saying, only that he was heading somewhere when a few moments ago he’d been at a dead end. How could he speak to packed courtrooms but not his daughter?

Her brow furrowed and she seemed on the verge of saying something. But then she stopped. This was a terrible idea. He should let her go. All of his earlier efforts had been futile. Why did he think he could help her now?

Tears coursed down her cheeks, shiny wet ribbons. This time the sight of her crying did a strange thing to him. A lump formed in his throat. He hadn’t cried in years, not even at Olivia’s funeral. He swallowed hard. Hayley moved toward him. She buried her face in his chest. His body tensed—it had been such a long time since he’d been touched—but then he smelled her hair. The same long ago, little-girl scent. Like roses, like baby powder, sweeter even. Daniel closed his eyes. He remembered: chasing her in the pool, tickling her stomach, making her scream with laughter. He’d never felt happier than on those days. Summer was coming. A few months away. This summer he would make her sadness go away. It might take some time, but he’d do it. He’d kept the Marilyn Monroes alive. He could do anything. At least, he could keep trying.

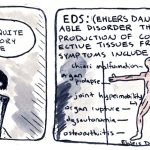

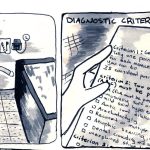

Independence: A Memoir of Illness, Inaccess & Objectification

Two Poems

To My Caring and Worried Mother

There are sliced carrots in the shape of a cowbell,

because I understand

that great food should sing to you.

There’s a movie we’ve never seen before

and a Japanese instruction manual.

There’s a novel about Alzheimer’s

and some magic memory pills for your mother.

There’s an automatic food dispenser

so you don’t have to bend down to feed the dogs anymore.

There’s a travel bag with a Bible

and a plane ticket to Paris.

There’s a color-coded flow chart

describing the best way to carry a conversation with Grandma.

In the bottom right hand corner, in fine print, it explains

you may have to adopt new tactics on the fly.

I caught Grandma watching

The Hulk in Spanish today.

I just flipped to the English version.

To my caring and worried mother:

raising your voice won’t help,

there is no cure.

All the Post-It notes

on all the cabinets

should say: open with caution,

eat with intensity,

remember,

we love you

and we’ll help you

find the watch

you stuffed in the cookie jar.

Elegy

The horse

nuzzles the back of my hand

as if the damp home of its nose

could stand not one more dark

second of this unfettered freeze.

What of it,

she asks after we’ve had our hot

meat and stale versions of drug,

sitting in lotus pose

facing my grandfather’s headstone

where every engraved sentence

curved tinsel of truth

into the steaming mouth of myth.

This barrel-bellied man

made a small southern town

seem like a place God had visited

and forgot to bless.

He was that damn bold,

that unforgettable.

Love Like Orange

My father’s love was orange. It could be warm and milky like summer Creamsicles, boisterous and magnetic as a dancing flame, or deep and foreboding as the morning sunrises sailors avoid. Every Saturday morning, he clocked in, arriving at my grandmother’s house at nine in the morning. My brother, Justin, and I waited at the front screen door, fidgeting and rocking in our criss-cross-applesauce positions, my mother standing in another room biting her nails.

We only needed our ears to alert us of his arrival: the slow whir of a car driving past the house followed by the crunch of gravel as it made a U-turn. The barely detectable squeak of brakes as a car came to a stop. The slam of a heavy door closing, the clap of footsteps, and, finally, the chirp of the car announcing the locking of its doors.

Sometimes he arrived bearing gifts of the stuffed bear variety or a chocolate orange wrapped in bright tinfoil that, to us, was as valuable as real gold. And other times he arrived in ghoulish masks to terrify Justin.

“For Christ’s sake, stop being a baby,” he barked in irritation, removing the Alf mask as my brother sobbed and hiccupped from fright.

“He’s only three; of course he’s scared,” my mother cried, stroking Justin’s back.

“You’re always babying him.”

These standoffs between my parents could last for as few as thirty seconds and as long as weeks. Tears could quickly turn to laughter as we climbed the apricot tree, bright green with orange fuzzy polka dots hanging from limbs and littering the grass.

In the backyard, Justin giggled while swaying forward and back in a swing fashioned out of a splintered four-by-two plank and manila rope as course as sandpaper.

“Higher,” he laughed. Our father obliged.

He was ours until sunset when he clocked out just as swiftly as he’d arrived. While walking to his car, we sent him off with a parade of waves, parroting “Bye! Bye! Bye! Bye!” back and forth as if he were leaving for war and we didn’t know when he’d return. The bright orange sky bounced off his car as it pulled out onto the road.

We waved with our apricot-stained hands until his car disappeared down the street. These days escaped us in a blur of tickles and laughs and tears and shouts and sweet coos of love. We would forget almost everything except the tang of orange that sat bitterly on our tongues.

—

My father’s love was indigo, as deep and distant as the continental slope we feared would swallow us whole. Sitting on his shoulders, I levitated five feet and nine inches above the ground, scanning the ocean for whales we’d never see this far south.

“Be careful,” my mother warned, which only instigated him to run.

I bounced on his bony shoulders, and then slipped forward and onto the sand. My mother and Justin screamed, and my father scowled, an electrical current of smoky, rich blue pulsating from his veins. Above me, furrowed brows and wide eyes collided, but all I saw were their indigo shadows wrestling on the sand. My mother surrendered, but my father’s palms were stained electric. He stormed ahead of us at a gait our legs couldn’t match.

We called for him: “Wait! Wait! Wait!”

He was too far ahead and could only hear the waves and seagulls, or so he said later. We lost him among the sea of beach umbrellas and Styrofoam coolers and barbeque smoke and waxed surfboards.

On the pier, we had a better view, and we each claimed a direction to survey. We spun around hoping to pinpoint the man with dark hair, dark eyes, and tanned skin. My mother always said he looked like a Greek fisherman, so we looked to the ocean beyond the end of the pier for the dark shadow of a man who’d had enough of life on land and all that comes with it. We felt for his currents of indigo that connected him to us like an invisible leash that tied families together.

“Frank!” my mother shouted.

“Papa, papa, papa,” Justin and I repeated.

And then, as always, he materialized behind us.

“I’m right here; you can stop making a goddamn scene with your hysterics.”

If there’s one thing my father hated more than life among mortals, it was attention from them. We followed him back to the car, our legs marching in double-time to keep up with his long strides. He fought in Vietnam, but the leave-no-man-behind warrior ethos did not apply here. Our feet sunk as the sand grabbed at our ankles, and we hoped we wouldn’t be left behind.

—

My father’s love was cherry—tart and sweet in the same bite. It was layered with unexpected gestures we loved and hated and from which we ran away only to return and beg for more.

On Christmas, we saw life through cherry-stained glasses. Our living room transformed into New York City, with the dozens of crimson-wrapped gifts as its skyscrapers. It took hours to unwrap everything, and when it was over, we hunted for more and painted our father red with tinsel and kisses.

With flushed cheeks and dilated pupils, we ran in circles, incapable of exhausting ourselves. We scrambled up couches like Mount Everest and excavated cardboard boxes for buried treasures, stopping only for a bite of chocolate from our stockings.

“That’s enough,” my father warned us. He was jubilant until he wasn’t.

I always received half a dozen warnings, but Justin was only given two, which was never enough for him.

“That’s two,” my father barked, standing from his seat.

Justin screamed and ran for shelter. When they returned from the back bedroom minutes later, one of Justin’s wrists matched the scarlet of my father’s right palm; it was what inadvertently linked them, like father-and-son tattoos that faded and then returned weeks later.

Justin’s eyes were carmine from crying, and I wondered if everything he saw was the color of Christmas. He rubbed his wrist while I connected the constellation of kisses left behind from my mother’s ruby lipstick that stained his cheek and forehead.

—

My father’s love was white—silent and opaque, hovering in a corner just above our reach. When it wasn’t bright and all-encompassing, it was the very absence of light, siphoning its warm comfort that engulfed us moments ago.

While Justin and I lived with our mother and grandmother in a rugged and familiar landscape of chipped paint, peeling wallpaper, and nail polish–stained quilts, my father lived in a glass castle, off limits except for today.

His house was a museum with carefully placed breakables that toed the edges of shelves. There were white ceramic vases with silk flowers, bronze elephants that, at the right time of day, sparkled under the skylight. There were hand-painted boxes from Russia, miniature Chinese floral vases, a globe made from rare minerals, and a cream-colored bust of Poseidon. They were untouchables we stared at with open jaws and wide eyes while on tip-toes, stroking the invisible barrier that hovered around each one.

We ran in the white glow of this castle until my father’s forty-five-year-old hands caught Justin’s three-year-old neck and forced him to the ground.

“How many times have I told you to be careful? You can’t just run around like a goddamn monkey. This isn’t a zoo!”

His booming voice had the incredible ability to vibrate through our bodies and cause our bones to shake in fear. Justin’s face turned white and, with wide eyes, looked pleadingly at my mother.

Disgust washed over my father’s face.

“Go. Run to your mother.”

“Go to him. You need to go with him,” my mother whispered to me.

I shook my head.

“Go, or he’ll just get angrier,” she pleaded.

I was the only one who could placate my father, a badge of honor I would have done anything to shed. After my father died, these memories felt traitorous. I would spend years repainting my past, searching for new hues, but I always returned to the same four, ending with this blinding white that would never fade.

Refusing to look back at my mother or brother, I stomped toward my father who snarled like a mountain lion in his cave of an office. My brother and mother retreated to a corner, licking their wounds. I cajoled my father with pleas for mercy and, eventually, guided him back to the living room where we lapped up his renewed love like milk.

Two Poems: 2001 & Barbie

2001

There was no space odyssey.

Instead, more than towers fell

in the city where I live.

People were still counting

paper scraps in Florida

for the sake of a flawed process.

People were still dying

in Gujarat’s earthquaked cracks

in Ghana’s stampeded stadiums

and in the summer of the media

calling shark attacks on Santa Rosa

a national security threat.

The Taliban’s advent, McVeigh’s execution

for destroying what seemed an entire city.

I had just turned seven.

For my birthday, my mother

bought me a Beatles CD.

Later that year, George Harrison died—

my favorite one, the one

who sang about how all things must

come to an end. But

how were endings possible

in a new millennium? New

Wikipedia, where we learned

how to summarize. New Nokia,

new Madonna, even language felt

refreshed: A.I., iTunes, OS X, Xbox.

It was the first time I broke my arm

in two separate places. I visited the zoo

and watched the animals roar at each other,

and at themselves. My mother dispelled

Santa Claus, perhaps a year too soon

for my imagination to take. I cried

until I received extra presents

for keeping the secret from my sister.

I saw myself in the Backstreet Boys,

in the highest rated Super Bowl in history,

as Harry Potter, whether philosopher

or sorcerer. Everything still felt possible

to a seven-year-old, who had just

heard about the first tourist in space

and thought it was an odyssey.

Barbie

I comb my hair with a small hairbrush.

I no longer walk in nature. And when

I sit on the front porch, sipping

whatever’s left from the mason jar

filled with all that last night, I flick

the maggots from my skin.

The parked car outside the house

sits with its tarped over cover since before

I remember. I remember

playing dolls with my sister

while my father wedged a football

into my hands, and said

you must throw as far as you can.

Open wide, my arms onto the wheel

where I learned how a man

drives five miles above the limit.

It was cold that first Kentucky,

where I first kissed masculine lips,

wet as leather, chapped the way

we hid from what we learned

in locker rooms. We grazed the sides

of our heads against the Cypress bark.

While we leaned against its trunk, I saw

pigs in the distance, wrestling

in the nightmud. They cannot know

how soon they will be separated, then skinned.

I Wake at Four & Drive to the Mountains

To leave the inner critic on the empty street beneath my windows.

To outride the arrows, or slings at least, of civic life.

To put the forces separating me from my daughter—the moderator

in elastic-waisted slacks, the decree signed

by the liver-spotted judge—in the rear-view.

To look ahead and see the world’s impersonal love song again

lifted from night.

To know the song is about the attention we give the wild,

unfixable everything we love yet is always already

indifferent to us.

And yet to see the sun rise, like a couched friend, from blankets of fog

in the lowland orchards.

To see the fields of our anxieties cut and gathered in silos.

To hear the wind wrap us, undeserving, in the sun’s resolve

to sustain us another day.

To stuff a campsite into my backpack and somehow walk ten miles.

To feel the weight of our basic needs shouldered across streams,

over hills, up crevices.

To remember having walked the home-forsaken trail before.

To realize I’d compressed memory of all this pain—all but the sacrament

of red, gold and orange leaves

above river bluffs.

Only here do I realize I must have forgotten just how many uphills,

just how fucking much elevation hurts.

Here I think such thoughts as our sapiens ancestors ground as many miles

over mountains each day.

I wake and drive and walk to think: Perhaps the downhill mortar and pestle

of our patellae almost crushes recall

of profane elevation.

And to meet the inner critic, somehow already at the top, and

to accept his message:

You wake at four and drive to the mountains

to accept the body’s pain as the cost of all the beauty there is to see.

To My Fellow Submitters

A found poem from sample rejections saved in “My Submissions,”

completed in response to a writing prompt given at

the Sandhill Writers Retreat, May 2019

Dear

Dear

Dear

Our poets’ community is lucky to have you

Good fortune in all your future writing

Declined

Cannot offer

We enjoyed having the chance to read

Many excellent entries this year

The team wishes you

We wish each of you the best in finding publishers

All the best

Unfortunately

The sweat and the perseverance it takes to put together a submission and send it out, naked

Declined by

Not Selected

A strong and competitive batch

A complimentary copy of this year’s

We regret

We are grateful for your ideas

We encourage you to submit again in the future

We are unable to provide individual feedback

Thanks

Best

Appreciate the dedication to craft

Thank you for choosing us

Hope that you and your work succeed in finding a home

You’re now one step closer to getting that acceptance you’ve been looking for

Sincerely

In peace and poetry

The Ball Spun

I arrived at the playground with Armin. It was a late afternoon in June; the rays of sunshine broke through the thick white clouds in places, illuminating patches of the tramped grass. Armin’s parents had sent him another package, a brand-new soccer ball in it. It was yellow with blue spots. He held it close to his chest as we sauntered down the street to the playground.

Armin and I hung out regularly. He lived in my neighborhood with his grandma. Armin’s parents worked in Austria as guest workers. Most of his life he spent with his grandma, seeing his parents once a year. Armin had toys I’d never seen before: remote-operated cars built of high-quality steel, model planes, and handheld video games. He brought to school all sorts of foreign candy, neatly wrapped, colorful, with pictures of cartoon characters.

Armin talked a lot, while I was a quiet type. He talked so much on our way to school that we often ended up being late. When I stopped by his place before school, I’d find him in the bathroom in front of the mirror, looking at himself and combing his blond curls. “What do you think, Edi?” he’d say. “Looking good, man. That schmuck, Sinan, is a goner. Selma is my girl. Hey, let me show you a new thing I got.” He was never ready on time, and the school was three kilometers away—a long walk.

The playground was deserted. We started kicking the ball from one rusted goal post to another. A few minutes later, we noticed a group of boys walking towards us. They were in their late teens. As soon as we saw them we knew we were in trouble. After all, two eleven-year-olds stood no chance against a gang of high-schoolers. Their ring leaders were two brothers. The older brother, Kasim, was as dark as the asphalt on the road he’d just crossed. He was skinny and long—all limbs. His round head bobbed on top of his body like a ball with two black eyes perched above a bulbous nose. Kasim’s brother, Vedad, was a year younger. He had long, brown hair he’d always tie into a ponytail. Vedad was notorious for his vicious smile that revealed two long canines. He was short and sturdy, his legs sinewy and fast. He was the best soccer player in town.

Kasim intercepted our pass and took the ball. Vedad shouted, “Come on, man! Be nice and share.” Kasim kicked the ball hard to the other three boys trudging behind him.

“Give the ball back, assholes!” Armin blurted out, and before finishing the sentence he looked at me, surprised by his own words.

“Whoa, man! The kid’s got a foul mouth.” Kasim sniggered. “Isn’t that Aunt Zinka’s grandson?”

“Time to teach him a lesson,” Vedad said. He picked up the ball like a pro, bouncing it on his knees, his ponytail prancing up and down. “Tell me, little punk!” he said. “Whose ball is this? It’s damn good. Real leather. Made in Germany.”

“It’s mine,” Armin said.

“Of course, little chicken shit.” Vedad said. “Did your mama send it from Germany?”

“From Austria,” Armin shot back.

“Would you, please, give us the ball back?” I interjected.

“This one here is a nice boy.” Vedad nodded towards me and balanced the ball between his foot and his shin.

“Listen, nice boy,” he said. “I have an idea. You get the ball and we let you play if you two show us your kung fu skills.”

“No way,” Armin cried. “You guys will mow the lawn with us.”

“Who said we’d do anything?” Kasim said. “We don’t fight little pussycats. We want you to fight each other.”

“Why would we do that?” I said.

“Because that’s the only way you get the ball back. And if you beat this mama’s boy, the ball is yours. Isn’t that so, mama’s boy?”

Armin looked at me, then at Vedad and Kasim. “The ball is mine,” he said.

I held my gaze on Kasim and nodded hesitantly. As long as I could remember, the only soccer ball I ever had was a bubamara, which meant ladybug. The bubamaras were often the only choice for the working-class kids in Yugoslavia. They were made of cheap rubber and lasted only for a few weeks. After a couple of good games, bubamaras turned into sad-looking, egg-shaped spheres, their innards dangling through the ripped outer layer.

I was bigger than Armin and stronger. Armin was all mouth, that cocky fool. We both knew I could take him out easily. I walked over to where he stood and looked at him up close.

“Let’s do this,” Armin said and jumped on me, climbing on my shoulder. He got me in a choke hold and held me down with all his might. Everybody lined up around us, grunting, yelling, and laughing—Kasim and Vedad in the opposite corners. I steadied myself, not letting him push me down on my knees.

I wiggled out of Armin’s hold and was about to strike him, but Vedad and Kasim grabbed us and pulled us apart. I felt Kasim’s firm grip on my elbows.

“Listen,” he shouted over my head. “You two start when we say.” He shook my whole body as if to reset me and said, “Now you go.”

I was fast this time. I tackled Armin to the ground and shoved his face into the grass. Kneeling on his back, I bent one of his arms backwards and held it tight, twisting and bending it towards his shoulder blades. After a few minutes he stopped wriggling.

The brothers pulled us apart again. Vedad laughed and said, “Man, that was ugly. But fun.”

Gasping for air, I gaped at his wolf teeth. He’d drawn his lips up to his ears.

Armin was in tears. “Asshole!” he screamed at me. “You’ll pay for this.” He ran towards home.

Kasim took the ball in his hands and spun it on his forefinger. “Get lost, nice boy,” he said.

—

Three years later, Armin and I were on the playground again when eight-year-old twins, Mirza and Kenan, saw us from across the field and ran over to our side. They were both dark and so skinny that they looked like two roosters—their noses stuck out like two beaks, their small eyes peered from creased, dry skin. The boys looked like two old men trapped in children’s bodies. They were Roma kids. Their mother worked at the textile mill; their father was rarely around, but when he was home he’d wave at me and smile if he saw me walk by their house. We could never tell the twins apart, but this time one of them had scabs all over his head. His brother had only a few on his neck and elbows. The scabby one was Mirza.

“We want to play too,” Mirza croaked.

“Really, you little toad?” Armin raised his blond brows and smiled. “You want to play with the big boys?”

“Yes, of course,” Mirza said. His brother stood by him quietly.

“What can you give us for it?” I asked. I knew they had nothing to offer, but I liked to joke with them. The twins were dear to me.

“Nothing.”

“How about you put on a nice show for us?” said Armin. “You just have to fight a little, like in the movies.”

“You’re too big for us.”

“No, you chicken shit, you fight each other. The winner gets this ball.”

I looked at Armin askance. I couldn’t believe he’d give them the ball.

“We’re brothers.”

“Brothers fight,” I said.” You sometimes fight, don’t you?”

“Yes, we do. But Mama says if she sees us fighting again, she’ll break our arms.”

“Your mother is getting off work in an hour,” Armin said. “The ball is yours if you win.”

By now, Armin had six soccer balls and counting. His parents had brought him a ball every time they came to visit from Austria. Three years earlier, he had told his grandma about our fight. The day after he told her, I got a whipping from my father. A few months later, after we got over our fight, I asked Armin if he’d gotten his ball back. He shrugged and said he couldn’t care less. He was quiet all the way to school that day.

Mirza looked at his brother. Kenan was still silent. “Let’s do this,” Kenan said and

leaped onto Mirza.

They alternately held each other in chokeholds at first, squirming around like two hungry worms. We pulled them apart. “We’re taking a break,” I said, restraining Mirza from jumping on his brother again. I held him tight in my arms, his scabs close to my face.

“Let them go,” Armin said and pushed his twin into the middle of our circle. I released mine and he lunged ahead. We stepped back and watched them. I glanced at Armin. His lips were stretched into a smile, his foot resting on the ball.

The twins battered each other with their bony fists. Their knuckles found their heads and faces. Soon they both were bleeding. Kenan’s lip was cut open. Mirza’s nose was oozing blood. I ran over to Mirza and yanked him away. The scabs on his head were cut open and bloody too. He left red streaks on his brother’s shirt. They both were crying now. “I’ll kill him! I’ll kill the bastard,” Mirza hissed through tears and blood.

I pulled up the hem of Mirza’s shirt to his face, took his hand, and pressed it on his nose to stop the bleeding. In a calm but threatening tone, I said, “Go home, right away, before I beat the shit out of you.” His brother held his lip and mumbled something about cracking Mirza’s scabby head open. Mirza started running. Kenan scrammed after him. They both ran towards their home, their shirts torn and bloody.

I turned to Armin. His mouth was agape, his lips moving, but there was no sound. I looked down at the ball in front of him. It was unblemished, sparkly white with black spots and a large Adidas sign on it. An intense burn welled up from the pit of my stomach. I sprinted towards the ball and kicked it with all my might. The ball soared high into the broad blue sky.

Things You Left in Accra before Moving to the Bronx

Grandma and her weak leg,

your sister at 18, still with one good iris,

your mother’s British jewelry hidden under the bed,

the places in the carpet you soiled with urine,

all the red dust,

your seat at Calvary Methodist Church next to Marie

who’d always chat with you when someone talked

about Jesus and his power to bring you all the things you needed,

your gymnastic booty shorts (your mother sent

them from America because the heat in Accra overwhelmed

you but you still wish you’d saved some for America’s winters),

warm Tea Bread sold at the YMCA between 6:30 am and 7:30 am,

the scent of air conditioning and ice cream at the SHELL gas station,

Grandma with her good English,

Mercedes and Pamela, your neighbors who borrowed everything from salt to ladles,

Asaana, Yooyi, Aluguntuguin, Nkontomire,

Living Bitters, Mercy Cream, Lion’s Ointment &

a Saturday listening to wind turn on pawpaw leaves.

Summer III

Across the forest, we sit

in a deer stand shaped like a heart.

A cry comes from the center of the woods

like wind blowing through a doll’s head.

There are birds that come out at night

just to be devoured by other birds.

I can’t make things happen faster

than they’re going to happen.

I know that now.

If your thick arms come out

of the shadows only to light smokes

or hold my hand expertly in yours,

I need to accept it.

when I stopped fearing ghosts

I learned about ghost hunting from my mom. When I was in elementary school, she drove me down to Louisiana every summer, and we’d stomp around the boggy summer heat in old cemeteries, reviewing etched tombstones, trying to find the names and death details for her ancestors.

We slogged through swamps, heavily forested areas where the heat bugs hissed so loud, I could barely hear when she called to me. We went all over the state—Mansfield, Baton Rouge, Grand Chenier. We stayed with friends in between, drinking sweet tea and eating collard greens, cornbread slathered with slices of cold butter. I was never quite sure what my mom was looking for, or why we needed to find it out there in the heat.

My mom was bad at picking up on things. That’s why she didn’t notice at first when a spirit latched onto her one summer in Louisiana. It just slipped out of the gravestone and sunk its claws into her, like a bad smell. The thing held tight to her all the way back to rural Vermont where we lived. I didn’t notice it at first. But then, a month or two later, it made itself known when she and I were alone at her office building one night.

The office building where my mom worked was four stories—a first floor, second, an attic, and a basement. I hated the second floor. It was dark and full of offices, crowded and narrow. Whenever I stayed late with my mom, I lingered on the first floor in an open office space, next to a large row of windows.

Sometimes she worked upstairs, and that night, she was working out of her boss’s office when I went upstairs to ask her for food money. It was dark, and the lights were off in the hallway. “Mom, can I get food money?”

“For what?”

“I want to go across the street.”

She hesitated, then rustled around, appearing in the doorway at the other end of the hall. There were at least five doors between us—five different offices along the hall. Some were open, some partially, one closed. I stood at one end of them. My mom was at the other. We looked at each other for a moment, and then I got the sense that something was wrong. I remember my skin prickling, like getting goosebumps in the cold, and then one of the open doors slammed shut.

My chest tightened. I felt the fear in my chest before my brain could register what happened. A second later, I went running for my mom.

+++

Twenty years later, I move from Vermont down to St. Pete, Florida, seeking the heat of my childhood. I get a tiny studio apartment and a new job working in development at a legal aid firm.

My ex-boss from Vermont texts me once a week. I keep the selfies she sends me saved in my phone and look at them when I miss her. I’m still in love with her, even though she’s married now, and I’ve moved two thousand miles away. In her texts, she tells me I’m pretty. She asks about the grants I’m writing at my new job, the beach, my friends. You’re pretty AND smart, she says, when I send her a selfie at my office. Her paragraphs always include winky faces. She doesn’t say much about herself.

After settling into my new office at my new job in St. Pete, I decide to decorate my desk. It’s black and chic and empty, so I print out pictures of me with my four best friends and tape them up on one of the monitors. There’s an empty space at the bottom. I leave it for a day, then print one of the selfies Lauren sent me and tape it up.

Back when I worked with her, Lauren and I spent eight to ten hours a day together. We went on field trips—to Stowe, to the islands, to happy hours. She told me once, on a longer trip, that things weren’t so easy for her as a child.

“But you’re so good with your dad,” I said. “You guys are like best friends.”

“It wasn’t always like that.”

“What was it like, then?”

Her mouth tightened. She was always doing weird things with her mouth – pursing her lips, parting her lips when she concentrated, these uncomfortable, awkward things that I loved watching. Sometimes, I felt her face moved on its own, like something else was guiding her that she couldn’t see or understand. “One time my brother and I were fighting, and Dad came up and,” she gestured with her hands, “wham. Knocked our heads together.”

“What was it like with your brother?”

“We hated each other,” she said. I asked why. She told me he could never forgive her for something. I waited for her to tell me what. She never did.

After two or three days of having her picture up at the office, I take it off the computer monitor and tuck it away inside my desk. I don’t look at it often, but sometimes, when I get out tea to brew, her face will come into view—the blonde hair, the freckles. Every time I see it, I think about those months I spent listening to her plan her wedding, talking about bridesmaids and dinner menus. I think about all the times I cried in the bathroom. How her face tightened when I told her I liked her. How inferior I felt standing next to her fiancé. How she looked at him like I wasn’t even there at all.

Yet every time I get close to throwing her picture away, she’ll text again.

I miss you, pretty, she’ll say and send a new selfie. I hope you’re enjoying your new life.

+++

The ghost that followed my mom home wasn’t malevolent, but it liked attention. It tapped on the walls at her work when she stayed late with me, large knocks on the plaster, as if someone were stuck in there from the other side. It ran up and down corridors and through the hallways. It smelled like cigarette smoke. The scent would balloon out, linger, then move. I’d sit there alone at night and all of a sudden the scent would creep up, eerie as a cold night wind, slipping its arms around me.

The next year, I started staying home alone at night instead of going to work with Mom, and the sounds disappeared. The spirit went away.

“You didn’t hear from her?” I’d ask my mom, day after day.

“Nothing,” she said. “Must’ve gone home with somebody else.”

I thought about the ghost off and on, wondering where it went, but as I grew, my interests diverged outward, and I thought about it less and less. Other things began taking up my time—basketball, grades, friendships.

In the seventh grade, I fell in love for the first time. Gina was short with long hair and a crooked smile. She was also my biology teacher. I hung around with her after school every day, and she paid special attention to me. I thought it was because she loved me.

It wasn’t until later that I found out she had a sexual relationship with a boy only a year older than me. She was fired immediately and, in the following months, lied to me repeatedly, begging me to help her get her job back, telling me she loved me. She missed me, she said. She asked about school, about sports, like nothing bad had ever happened.

After months and months, I stopped emailing her back. It hurt to be in contact with her. I felt creepy and weird, and thought there was something wrong with me for loving someone who’d done something so bad.

Still, even after cutting off contact, I thought about her. My thoughts eventually became less about missing her, and more about trying to understand what she had done. Why had she done it? Why did she lie to me? Why did she pretend she cared?

That’s the part that haunted me. I thought she loved me like I loved her. But she never really did.

+++

After I finally stop talking to Lauren, I go on my first date in over a year. I walk downtown in a button-up shirt and skinny jeans, sweat pinching under my arms as a cool breeze snakes in through my shirt sleeves. I’m early, so I grab a beer across the street at a local gay bar and watch the crowd around the coffee shop across the street where I’m supposed to meet my date.

We’ve been talking for a few weeks now, and I really like her. She’s in her early forties, and a therapist. She communicates well and gives me space when I need it. I like her boundaries and her maturity. I like how she looks and what she does for a job and how giving she can be.

I spot her walking in and finish up my beer, then head over. She recognizes me immediately and opens her arms for a hug. We sit at a porcelain bar, and she orders a fancy coffee while I get a beer. We make small talk at first, then ease into a conversation. I try to keep my mind on the present and not the worries burbling in my stomach. Everything seems to go well. After two hours, she heads off to a dinner with her friends. I visit a friend, too, at a bar down the street, and we talk until it’s pitch black outside and the wind gets too cold for sitting outside anymore.

It’s on the walk back that I start to panic.

This woman is beautiful, successful, and healthy. What could she possibly want from me? I worry about what I said during our date, how I acted. I worry I’m going to end up liking her too much and then she is never going to like me back the same way.

After crawling into bed, I start to cry. The wind is strong and cold in a way I never expected Florida to be. I stay huddled in the blankets, my face pressed to the pillow.

I didn’t stop dating just because Lauren broke my heart. I stopped dating because it’s just too hard. I can’t like someone without immediately wondering how they will hurt me, like Lauren hurt me, and Gina. It’s been fifteen years now since she was fired, but she still pops up sometimes, slipping out somewhere from the shadows, this little voice telling me that she is going to leave. She is going to hurt you, like all the women you love. I don’t know how to shut it off or make it go away.

+++

After leaving Vermont, I spent five weeks on an “art farm” in rural Nebraska to work on my writing. There, I learned how to install drywall, build survival fires, and cohabitate with field mice. The house I lived in was more than a hundred years old and had been transplanted to Nebraska without its foundation, then built back up into something that could stand alone.

The bones of the house had potential. They were wood, weathered and old, but with moments of stark beauty. The house was slightly crooked, too, and with the additions that had been made on the western wall, it looked like it had a face—two eyes, a nose, and a zippered mouth.

When I first arrived, I was terribly uncomfortable in the house. There were too many people there, too much going on. But after it started getting cold, and everybody left, I transferred bedrooms and began liking the space much better.

I started noticing the phantom noises during the afternoons. I’d sit downstairs in the kitchen drinking tea and writing, and I’d hear footsteps above me. My roommates had work studios elsewhere, and I was alone. I’d call out. Listen to the silence. Then it would start up again. It went away when my roommates were there, but on several occasions when I was nestled in bed, I got the distinct feeling there was something else in the room with me, standing at the edge of my bed.

One night, I had a dream that I was a little boy away at a boarding school in Greece. I saw everything from his perspective—the cliffs above the sea, white foam crashing, the old school uniforms, the sunlight. I’d never had a dream from someone else’s perspective before. I told my roommates about it the next morning.

“Could’ve been a past life dream,” one of them said.

We all sat downstairs, sipping tea and coffee as the sun burned in through the windows. The smell of buttered toast hung in the air. “Or it could’ve been a memory from someone who died in here,” the other said.

I went about the remainder of my time in Nebraska believing there was a lonely child ghost in that house, just looking for a friend. I played music in the afternoons to cover up his stomping. Before I went to bed, I said goodnight to him. I told him to rest while we were all asleep.

Nebraska was where I stopped fearing ghosts. Nebraska was also where I unfriended Lauren on Facebook because I couldn’t stand to see any more of her wedding pictures. It was where I cried in my sleep, and dreamed about her, and tortured myself wondering what I had done wrong, what I could’ve done better to make her love me.

Most days, I woke up scared she would text me something about her new life with her new husband and I’d have to pretend, like I’d already done for a year, that everything was fine, and it didn’t tear me to shreds. Most nights, I went to bed afraid I would keep Lauren inside of me forever.

+++

A week after my date in St. Pete, I dream I’m living in a haunted house. It’s a large mansion with thinly made plywood on the outside, but with grandiose, Victorian-style decor on the inside. I go from room to room in the house with a feeling of dread at the back of my neck. I know something’s behind me, but I don’t want to turn around to look. The entire mansion is riddled with shadows, and I keep throwing open the curtains only to have them fall shut again when I move away.

Finally, I realize I have to go. I can’t stand it anymore. I pack up my car with all my things. I place some stuff on top of the car, twining rope around the door handles to keep everything in place. I hurry. I can feel the thing behind me, to the side of me, all around me.

After getting in the car and starting to drive away, my tension begins to ease. I look around at the trees. The pines hang low, their needles brushing the windshield as I drive.

Suddenly, the car engine sputters. I know then that the ghost is still with me, even though I’ve driven away. It’s hanging onto the car, trying to keep me from getting away. I fight with the stick shift, but the car slows. I’m driving downhill and hope the momentum will keep me going, but then I lose control of the steering. The car fishtails. I take a turn into some bushes and then for a second, it’s all green and moss and branches scraping at glass. At the end of the underbrush, my view clears. I’m at the edge of a cliff. Rocks kick up under the car. Panic grips my chest, but there’s nothing I can do. It’s too late.

I open my mouth to cry out and then I’m airborne, soaring over a hundred-foot fall, a rush of rapids waiting to devour me below.

+++

I wake up in the morning with that familiar feeling—that something else is in the room with me. It’s never happened in the St. Pete studio before, and the sensation is slightly different than it was in Nebraska. This morning, it’s more like this thing was with me and, as I woke, it slipped away.

I rise and make the bed. Shower. I bustle around in the tiny space, heating tea and stir-frying potatoes and eggs with onion and pepper. It’s cool out, and the sun peeks in through the blinds, falling in strips across the kitchen tile. I don’t have the sense of anything lingering anymore. It all faded as the sleep washed away from me.