Elizabeth Chapman

I fibbed to Ms. Vanderhooft. It was her word “beginner” that bothered me. The word gave the wrong impression of my experience. Technically, no, I’d never taken a formal piano lesson before, but (and this held great importance in my seven-year-old mind), I lived in proximity to my sister’s playing, which was very good. The lie earned me a volume of impossible music. A system of horizontal lines that looked like fencing, and dots like scattered ants. I sat, silent, at the piano. Ms. Vanderhooft watered her ferns.

◊

Now, at fifty, I wish I’d been a journalist, or someone whose job it is to name paint colors. Instead, I have a piano studio of my own. I have a few Vanderhooftisms: I angle my grand like Ms. Vanderhooft did, over a Persian rug, like she had. I write students’ assignments like she did, using an extravagant, looped cursive. I have a fern. But the similarities end there. I’m less formal than Ms. Vanderhooft, and surely less intimidating.

My personal life is different too. Granted, Ms. Vanderhooft never shared much about her personal life, but I know she never married, which means her husband never suddenly landed his dream job, four states away. She never moved with him, closing her piano studio the week of her twenty-sixth wedding anniversary. She never, in the midst of unpacking, discovered his affair—the result of his sloppy texting. She never repacked her things. Never left him. She never attempted to relaunch her studio with an email sent from a bathroom floor. She never typed “Returning to Virginia” in a subject line, never wrote “leaving my husband” underneath, and she never, to my knowledge, found herself referencing a Gloria Gaynor song to let people know she was just fine.

◊

I slid the U-Haul into park sometime after dawn. The drive is a blur. I remember some gas station coffee. I remember toggling the radio: on to fill the silence, off to cut the noise, back on to fill the silence. I followed some vanity plates—a BCHLVER, a XOXO4U, a SATAN2, which begs the question. According to TikTok’s Therapy Keith, my mental fog is normal.

◊

I’ll be reoccupying the marital home while we sort out the terms of the divorce. The house didn’t sell in the month I was gone. My sister calls this circumstance a “God thing.” The place is a faux colonial, nestled in a neighborhood of shaded lawns but leafless driveways. Bucolic by way of tedium. I’m not the ideal resident. The HOA leaves me periodic notes: unapproved shutter color (blue), unapproved door color (also blue), unapproved mailbox, unapproved mailbox flag. This note, taped to my front door, reads, simply: “brick grout.” My married self would have laughed. I swing open the door and shove the letter into my pocket. It isn’t funny.

I unpack the studio first—the room just off the entry. I need the money. I roll the piano’s port side against the front windows and set my teaching chair to its right. I push our—my—dining table to a side wall and stage it as a workspace—lamp, laptop, calendar, candy dish. I mount a whiteboard low, just above the baseboards, and fill a basket with a rainbow of chubby, dry-erase markers. Three days later, I’m back in business.

◊

Owen, age eight, arrives at three. His wavy, red hair has deepened to maroon in the month I was away. I square the welcome mat with my foot as his mother escorts him up the driveway. She has him captured in a sideways embrace—the kind used in hostage situations.

“Hi, Owen!” I say.

No response.

“I have candy. On the desk.”

His mother leans in. “O is not exactly enthusiastic about returning to lessons.”

She turns to leave. I compliment her sweater.

Inside, Owen is standing over the dish of Jolly Ranchers. He has his investigation down to four economical motions:

Select, unwrap, lick, return.

Select, unwrap, lick, return.

I offer him a dry one and tip the rest into the trash.

He’s easily the least talented student I’ve ever taught. It isn’t just that Owen lacks some innate musical ability. The problem is his dislike for piano, which verges on histrionic. Today, his presentation is dermatological. He rubs his ears while we chat. (School was “fine.” His weekend was also “fine.”) He chases the itch down his back, twisting left, then right, like a toy on a swivel. I bribe him with dinosaur stickers before thumbing to the easiest piece I can find: “Mission to Mars.”

“Curve your fingers,” I say. He extends them. Rigid.

He and I have been at this impasse since his first lesson. Almost two years ago. “Play on your tips,” I’ve said. “Be gentle,” I’ve said. I’ve demonstrated, using a feathery voice. Last spring, we spent half a lesson lying on our backs, curling our hands into the soft domed shapes that “all good pianists have.” But the corrections never take.

“Okay,” I stop him. “Those are all the right notes. Well done on that. But this is ‘Mission to Mars,’ yeah?” I say. “And outer space has no gravity.”

No response.

“Right?”

I glance at the clock. Ten minutes have passed.

“So, float like an astronaut, on the tips of your fingers,” I say, my hands rising. “Weightless,” I add, hoping he’s interested.

He’s not. What evolves instead is an argument about gravity. Where it exists, where it doesn’t. I grab my phone and Google “gravity in space,” knowing the conversation should never have gotten this far. He sits cross-legged, listening, then parries. He has a rare condition, he tells me, making it painful for him to play with relaxed hands. It is especially excruciating—I assume this based on the tortured face he makes—for him to play with anything approximating curved fingers.

His medical revelation brings us to 3:30 p.m. I hand him his books, hold open the door. His mother waves. I wave back. I am a charlatan.

◊

A box from my husband arrives just after eight. Inside is the nub of a Maybelline brow pencil, two hair elastics, and four loose cotton balls. The postage on the top of the box reads $18.30. I walk the box to the outside trash barrel, and the barrel to the street. I slide a frozen pizza into the oven, and key his credit card number into a dating website, in the box marked Method of Payment. The lifetime premium package runs $849 if you decline all promotional offers.

◊

My next day’s students are siblings. They live in my neighborhood, and from the window, I can see their approach. Mabel, thirteen, is walking down the middle of the street, hunched and pumping her arms against the weight of a large purple backpack. Her brother, Sebastian, two years younger and twenty yards back, is traveling at the edge, following the crack that separates the road from the gutter. The shoestring of his right sneaker is dragging and flapping through a collection of wet sludge. This appears to be the goal.

I have mixed feelings about Mabel. On the one hand, I admire her. Here is a young girl who thinks fast and speaks her mind. She dismisses conventions, from fashion to politeness, and never misses an opportunity to lead. On the other hand, she’s annoying.

She looks taller today and wears one of those harnessed safety sashes, the neon yellow kind worn by crossing guards.

“Hall monitor sash,” she corrects me, swinging her backpack to the floor. “It’s my job to tell the other kids where to go.” The typecasting is exquisite.

Sebastian enters just behind. His sneakers squeak across the entry before falling silent on the carpeted staircase, where he sits, then winks. Newly acquired skill. I wink back.

I spend most of Mabel’s lesson assigning new music and trying to sell her on an arrangement of “Red River Valley.” She’s never heard it, which is fair. They’re not exactly popular, these American ballades. I demonstrate the piece and some sensitive timing I hope she’ll notice.

“Beautiful tune, right?” I say, holding the final notes.

She retakes the bench. I wait while she squeezes hand sanitizer into her cupped palm.

“And it’s nothing you can’t handle, if you practice,” I say. I mean it as encouragement. “So, twenty minutes a day, six days a week. Yes?” I’m drawing a practice chart in her spiral assignment notebook as I talk.

She flips the sanitizer closed and returns it to her backpack.

“Right?” I say. “Twenty minutes a day?”

“Well … Ms. Bellamy, the thing is, we are really busy.”

I reach for my coffee.

“Busy with what?” I’m imagining acceptable answers: travel, surgery, a funeral.

“We’re going to Disney World.”

Travel. Very good.

“Nice!” I say. “When do you leave?”

“It’s next spring. The thing is, my parents and I are busy discussing how to break the news to my school.”

Short of full-time employment, I tell her, she’s not busy.

◊

During Sebastian’s lesson, I learn that I can teach while I construct a dating profile. I answer the “Basic Information” questions to a rhythmically bereft “Jingle Bells.”

Age: 50

Height: 5’2”

The music has stopped.

“Is it a space note or a line note?” I ask.

“Space?”

He finds his note and proceeds.

Astrological sign: Cancer

Children: grown

Pets: no

“Half notes get what?”

“Two beats.”

“Right. Start back at measure ten?”

Smoking: never

◊

By evening, my Bumble profile is almost complete. Under “Interests” I scroll through dozens of sports, none of which apply. Under “Going Out” I click “cafés.” I choose “cities” from another list, without understanding what the choice commits me to. I mull the last step—the “About Me”—while I flatten the moving boxes I’ve emptied. I carry the flattened boxes to the garage. Cardboard is stacked as high as a car, right in the place his sedan used to sit. Memories of the marriage leave me tired. Just tired. Therapy Keith says I haven’t reached the pain portion of my healing journey. I’m not encouraged.

I peck out the final entry just before midnight.

“Life is good but I’m looking for my person. If you like conversation and believe vulnerability is a superpower, I’d love to chat.

I wake up to thirty-three likes.

◊

On the phone with my sister, I read the options. “There’s Mustang, 52, University of Pennsylvania. Under ‘About Me’ he writes ‘I am publish.’ ”

“But—” she starts.

“No, I thought of that. Born and raised in New Jersey. English is his first language.”

I scroll.

“There’s Trevor, 50,” I say. “He’s a ‘good man whose looking for a woman whose recovered from her woes of life and hasn’t gave up looking for someone to blame for what he done I am worthy of a chance.’ ”

“Doesn’t he mean someone who has gave up looking for someone to blame?” she says.

“Willie, 53, is a healer. But it says here he doesn’t have cable.”

“You’re being picky.”

“Under ‘Interests,’ this guy writes ‘COSTCO.’ And this is Bumble’s best. Just think about how good what’s-his-name would seem on a dating profile,” I say. “And he’s a complete asshole.”

I say “asshole” with a forced conviction, though. I mute the phone and pop another truffle into my mouth. Our marriage was easy. We didn’t say “I love you.” Literally, we never said it. We skipped straight to how much. “A line, not a segment,” we’d say, and it became our shorthand. Its comfort lay not just in the meaning of the phrase but in the privacy of its loop, closed tight as a hug. I said it in the mornings when he handed me coffee. I said it over my shoulder in the evenings, when he shooed me toward the piano. He said it as he left for work, holding the lunch I’d packed for him in the red-lidded Pyrex. He’d stopped taking my lunches toward the end, it occurs to me now. He’d been taking Lean Cuisines. He said he wanted to drop some weight. I take another truffle and unmute the phone to repeat the word “asshole.”

I hang up the phone and Google “affair and brain tumor.”

◊

I’m meeting a new student today. She’s an eleven-year-old girl who, for the last year, has had the misfortune of being taught piano by her mother.

“Ms. Bellamy, thank you for meeting with us,” the mother says. She seems to be working my name into each statement. “Yes, Ms. Bellamy, Gretchen has been playing for one year.” She looks at Gretchen, then back at me. “I brought her curriculum for you to see.” She pauses, and I think she’s forgotten, but she sneaks it in: “Ms. Bellamy.”

She unpacks a black valise as she speaks, fanning file folders across the piano lid like a nurse arranging surgical instruments. Blue for technique, yellow for theory, green for daily. Red is marked “FUN.” Then comes the binder—a cross-referencing system of curriculum, calendar, and progress reports. The presentation takes the better part of fifteen minutes, then she asks if she can lie down.

“Like, on a sofa?”

“Yes, Ms. Bellamy. Thank you.”

I point toward the den and turn to Gretchen. “Your mom feeling okay?”

She nods. “Oh, she’s good.”

I stare at Gretchen’s braids, plaits of curly hair, twisted into submission, and I imagine her mother, curled feline on my sofa, her head on my pillows, a drool stain forming. Pooling. I try standing her back up in my mind. She slumps at me, annoyed, then lies back down.

“What would you like to play?” I ask.

Gretchen thumbs to her latest piece. The notes, which come slowly, are like the words of a child learning to read—some right, some wrong, and none of them delivered in any relation to the next. I imagine my own halting delivery if I were asked to read aloud in Korean.

◊

My four o’clock student makes snoring noises over my instructions. He’s going to be quitting piano, he informs me. He needs more time for Pokèmon. Expect an email from his parents, he says, lying on the bench. “I will check my email every day,” I say, speaking to his eyelids.

4:30 p.m. refuses to use his third fingers, what non-pianists call middle fingers. “My parents wouldn’t want me to,” he says. “Sticking out your third fingers is short for a bad word.” I tell him that this rule doesn’t apply to pianists. He brightens. I worry he’s misunderstood.

Five o’clock draws me an army of stick men on my whiteboard, rather than the quarter notes we are studying. Through a line of innocent questioning, I discover that the men are not holding swords, as I had assumed.

◊

My 5:30 p.m. is an adult student. His name is Bill Dean, which is how he refers to himself. BillDean. He’s a retired Air Force colonel and fought in Vietnam. “A fighter pilot,” he adds, during introductions. BillDean is a spry eighty, with that wealthy fisherman look—tight white beard, pressed chinos, a half-zipped fleece—like Kenny Rogers advertising for Orvis. His reenrollment gave me some dread, but he pays on time.

“Now, Hannah, it’s hard for old BillDean to find this high note,” he narrates as he plays, “so sometimes I take a moment.”

“I get it.” I nod. “Try moving your hand earlier, during this rest,” I say, pointing.

“Now, listen,” he says, shaking his head.

“Look, Bill. There’s no point in playing complex music until your hands move properly. Think of it as protocol. You wouldn’t fly without completing the flight check, would you?”

He smiles and calls me Darlin’.

I assign “Pink Polly.”

◊

Therapy Keith wants me to establish a routine. I choose coffee. Coffee and Bumble. Frankly, I’m surprised by the number of bare-chested men I see online. Some bare-chested men hold beers toward the camera. Some hold recently caught fish. Others hold recently caught fish and beer. Then there are photos of bare-chested men leaning against their cars. Or their trucks. Others are on their motorcycles. One bare-chested gentleman straddles his motorcycle, holding what appears to be his infant daughter.

◊

McKinley, ten, is sobbing. Her parents have lied to her. And she’s pretty sure she “can never trust them again in her whole life because who would lie to their own child?” She repeats “own chiiiild” like a grieving mother. She sinks into silent-sob territory, and I wait for the breath that follows before offering her a chocolate. From what I can piece together, McKinley has spoken to Riley in the other fourth grade. Riley has an older brother who has a friend who has declared Santa to be “sus.”

“What?” I say, but the jig is up.

“It’s a trick.” Her eyes are still brimming. “It’s all from Target.”

I nod sympathetically and redirect her to the lesson. McKinley manages to lose herself in the music for a few minutes before her jagged inhales return.

“Talk to your parents,” I say, handing her another chocolate.

“I’ll sit them down after dinner,” she says, handing back the foil.

My own dinner is another frozen pizza. I add the black olives he always hated. Here is the upside of my broken marriage. Olives. I eat and load my plate into the dishwasher. Then I pause to remove my wedding band. What’s left behind is an indentation more noticeable than the ring itself.

◊

Noon today marks seven weeks since I received his text—the one meant for some unknown woman. I feel a stinging in my chest. Therapy Keith says it’s important to observe these sensations without trying to change them. As if changing them were possible.

I marvel that so many people have weathered this situation. It’s a little like you feel after you deliver a baby. For weeks, you see other mothers and think, really? You did this too? I hung pictures today, arranged a bookshelf. I sprayed some Lemon Pledge. My mother called this effort “puttering.” I suspect she puttered to lift her mood. It works a bit. I even find the courage to sit at the piano. But Mozart triggers memories of college practice rooms, closet-sized spaces, just large enough for a piano and a bench—and in our case, his bended-knee proposal. I can’t touch the Schubert he liked to hum, or the Debussy I was learning the day of his text. I play a scale and close the lid.

◊

Owen’s maroon hair bobs down my driveway. He’s unescorted today and claims to have practiced every day since his last lesson.

It’s impossible, since his music has been sitting on the lid of my piano all week. I say so, pointing to his books. “I did it by memory,” he says.

The noises that follow have no resemblance to the assignment, but his commitment to the moment is absolute. It is, in a way, the most impressive performance I’ve ever witnessed.

◊

I unpack the last two cardboard boxes tonight and find things I wish I hadn’t. Pressed flowers, loose pictures. One of us at nineteen, sharing an Orange Julius, another of us standing in front of our first house. The second box contains our wedding album. I flip to the final page, but backing into our memories is no safer. A candid photo stares back, one someone snapped as we left the reception. We’d made it as far as his Camry, rice in my veil. We’re beaming. I look at my eyes, staring back at me. And his. I see no guile.

I haul both boxes to the street.

◊

According to one website, a ring indentation can linger for a year, even two. “Please avoid any ring on your indented finger, until your finger has returned to its normal shape.”

No problem.

◊

Mabel’s “Red River Valley” is still unrecognizable. The problem is her pace. “It’s sluggish,” I say, watching a fine mist soak the boxes at the curb. “You’re sauntering.”

“I don’t know what that means,” she says, slow-blinking.

“Like, wandering. And you can’t just wander from note to note whenever you feel like it.”

“I can.”

“All right, you can, but wandering disrupts the flow. Do you know the song ‘Anti-Hero’?”

She exhales. A curt puff. “Okay, obviously. But what if Taylor just … meandered?”

“It’s me, Hi, I’m,” I sing, then stop.

“the”

“problem”

“it’s”

“Oh my god,” she says.

Sebastian hasn’t practiced either. He’s more interested in studying his feet. I watch the clock as he mashes the pedals, raising, lowering, and raising the damper mechanism. When the novelty wears off, I hand him his music. The “Jingle Bells” that follows is predictably slow and, like the previous week’s effort, sounds nothing like “Jingle Bells.” I squirm through his notes, each suspended from the time-space continuum. In the time it takes him to peck out a disjoined o’er the fields we go, I’ve written a grocery list. I straighten books to his laughing all the way, and by his bells on bobtails ring, I give in, feeding him answers, like the Google Maps voice.

“Yield for the whole note.”

“Proceed four beats.”

“Your destination is on the right.”

◊

I’m getting nowhere with BillDean either.

“If you’d curve your fingers, lower your wrists, and count the beats, you’d be playing the hell out of ‘Pink Polly,’ ” I say, but he’s already shaking his head.

“Goddamn it, Hannah.”

“What, Bill?”

He’s a fighter pilot, he reminds me. He wants to play “goddamned classical music.” Good music, he emphasizes as he reaches into his bag. “Good” comes down to two selections for him: “Danny Boy” and “The Man from Snowy River” (the titular movie’s theme song).

“The Man from Snowy River” is eleven pages long. It’s dense and difficult. If BillDean isn’t ready for the complexity of “Cat in the Hat,” this “Snowy River” is his Finnegans Wake. “Danny Boy” is no better.

“Now just listen,” he tells me.

Over the next ten minutes, BillDean finds a dozen notes—first on the page, and then on the keyboard. He’s bent and mumbling as he pecks, and most of what he says is inaudible. I catch a “Christ Almighty” and something about being a “goddamned patriot.”

◊

My attorney calls. If asshole and I can agree on the financial split, I can be divorced in thirty days. It’s been sixty-one days since we’ve spoken. Sixty-two days ago, my biggest fear was him dying first.

◊

I have noticed an unrealistic number of hikers on Bumble. Given the hundreds of times I’ve read “hiking” and “climbing,” every trail in Virginia should be jammed with middle-aged men.

The students are using my whiteboard as a kind of message center now. They’ve partitioned off a corner for me, which was thoughtful, and have asked me to keep my instructional diagrams within the confines of a wavy-line-and-dot pattern. The concept is the work of Haven, a fifth-grade girl with beautiful penmanship and inexhaustible organizing propensities. I agreed to the request, because why not. Besides, so far at least, I like the board’s content. Today’s entries include the creation of a book exchange by a boy who needs Book Three of the Warrior Cats series, a nice drawing of a dragon, and two uplifting reminders: “Find The Music You Love,” one student has written, encircling the words in a flowering vine. “It’s okay if you mess up,” another assures, the words speech-bubbling from a toothy orange sun wearing shades. Haven noticed the theme too. She roped the sentences off with more wavy lines and slapped the word ENCOURAGEMENT at the top.

◊

The blue minivan in the driveway means that Gretchen and her napping mother are here. My mouth is moving as I quietly plead for Mom to stay in the car, but Therapy Keith is wrong about manifesting your desires though positive thought.

“I’ll set my alarm,” she calls, walking toward the den.

◊

I spend the evening eating olives directly from the jar. A lot of the Bumble profiles I read start with the same line: “Looking for my partner in crime.” Men who say this are the same men who choose Bumble’s prompt “the quickest way to their heart.” Then they all write the same answer: “through my chest.” I’m developing a gender-wide ick.

I head for the stairs, flipping off lights, locking doors. Daily tasks remain oblique marital references. I linger by the piano, reaching to play a phrase, then sit, pajamaed, to play another. I pick Mozart for its rationality, but my playing sounds severe.

In the morning, I trim the Christmas tree. It doesn’t take long. The ornaments are ironic now. I unwrap “Our First Home” from its tissue paper and send it sailing. The twenty-five silver bells, etched with dates, make sickening thunks as they hit the back of the kitchen trash can.

◊

Mabel has practiced. You’ve got to hand it to her. Her “Red River Valley” is solid.

“I like what you’ve done with it,” I say. “The piece flows now—like musical sentences, telling the story. What do you think?”

“They’re not really sentences, though.”

And here we go.

“No, that’s true. The musical term we should be using is ‘phrase.’ ”

“Yeah, I don’t think of them as phrases, either.”

“Well, but they are phrases, actually.”

She shrugs. “Maybe.”

“Not maybe. That’s what they are. Those black lines over the notes are phrase markings.”

Silence.

“By definition.”

“Mmm.”

“What, mmm? It’s a fact.”

“It’s a fact to you.”

“It’s a fact, period. Unchangeable.”

“No, yeah. Unchangeable to you.”

I reach for my coffee and picture Mabel as Napoleon, jerking the crown from the hands of the Pope.

“It’s an F-sharp here,” I point. “Not F-natural,” I say. “As you played it.”

“What the fuck,” she mutters.

◊

BillDean is outraged again. He wants his country back. He’s sick to death of safe spaces and pronouns and everyone and their goddamned woke.

“Woke?” I say.

He’s just come from a rally. “The Governor was there and he goddamned loves us. He thanked us and thanked us. No goddamned government is going to take my guns, and I’d love to see them try.”

He sounds like Yosemite Sam.

◊

I scroll Bumble while the French press steeps. Therapy Keith would appreciate the consistency of my schedule.

“He’s standing next to a tank,” I say when my sister picks up. “In an ascot.”

“Stop,” she says.

“And get this,” I continue, reading the paragraph beneath the picture. “‘SWIPE LEFT if you work for the GOVERNMENT, are a scammer, STALKER, timewasting MORON, obsessed ex and her ‘entourage,’ or ENTITLED VEGAN LOSER.’”

“Just no.” My sister sounds sleepy.

I message him anyway.

“Oh,” he writes, “Those aren’t categories. Those are individual people. They know who they are.”

“Do you ever worry you seem, I don’t know, aggressive?”

He thanks me for being ladylike.

It’s not just the tank guy. “I’m sick of most of you,” one profile begins. “I’m not here to save you from your boring-ass life,” another warns. “Please be capable of intelligent conversation,” one specifies. There’s nothing wrong with that last request, I guess, except that there is.

◊

My final student this evening is also my youngest. The boy is five, with tiny blue Crocs and a pregnant mom in tow, her spine bowed into the signature S of the third trimester. I don’t interact with many expectant mothers. I did when I was younger, but I’ve aged out of knowing the latest in maternity fashion or baby gear. My ideas of newborn gizmos would strike her as my mother’s struck me: out of touch. The woman is having a girl, she tells me. But sometime during the list of possible baby names—Harper, Daphne, Pippa—the avalanche happens. Feelings first, followed by discernable thoughts. Memories. The work stories he shared. The reoccurring names. Name. My ears begin to ring. And like finally seeing the image in one of those random dot auto-stereograms, those Magic Eye pictures, you wonder how you ever missed something so plain. Because what pregnant woman calls her boss between contractions?

“Wren’s in labor,” he’d said, walking back into the room a few minutes later. “Dilated to four,” he said, checking the ringer on his phone.

We visited Wren the following week. Rang her doorbell. Gift in hand. I greeted the baby first, then handed Pippa to my husband. He held her all evening. On the way home, he talked about the baby. When we pulled into our driveway a few minutes later, he was still talking about her. Until suddenly he wasn’t.

“I sent Wren an email today,” he said. “A forward, really. Of our first office interaction.”

He’d titled the forward “Look How Far We’ve Come.”

By the time I say all of this to my sister, later in the evening, I’ve thought of a parade of other incidents. Altered routines, suspicious locations, dodgy answers.

She says nothing.

“If you saw this many clues in a movie you’d be insulted,” I say, filling the silence, then I pause too. Because there’s no explaining how sick you feel when you realize someone’s found pure joy at your expense.

“The baby visit,” she says, finally. “How long ago was that?”

She’s trying to construct a timeline, but I already have.

Three years.

◊

I spend the evening writing him an email.

“Hi” gets replaced with “Hello” then changed back to “Hi.”

Delete.

No salutation.

“How dare you,” I begin.

Delete.

“It has come to my attention,” I write.

Delete.

“I know that it’s Wren,” I write.

Then, hands shaking, I delete that too.

“I want the house.”

He waits twenty-four hours, then calls. I suspect his attorney has advised him, pointing out the danger of admitting anything in print. I put the phone on speaker, and set it on the coffee table, speaking to it from the doorway. Fifteen seconds later, the house is mine.

◊

I’ve had it with Owen’s playing. It isn’t improving, and frankly, he’s making me question my ability to teach. My new plan is to ignore his fingers. I’ll focus on his sound.

“Can you do it?” I say, playing a string of round tones.

Owen plays his notes. Each is a cataclysmic event.

“Let’s play echo,” I say. “I’ll be the loud shout, and you’ll be the soft echo.”

He rubs his neck. Overhand. Underhand. Overhand again.

“Know what an echo is, buddy?”

I demonstrate, shouting “echo.”

He shouts back.

I echo him quietly.

He shouts again.

◊

The staircase carpeting is loose. As Owen leaves, I give the lowest corner a yank. Disintegrated carpet backing flies up and rains down on my sneakers.

During Mabel’s lesson, I pull some more.

“What are you doing?”

“Nothing,” I call. “Your pedaling is late. Listen for clarity. One more time, please.”

The lowest step is free, and I’m admiring my own work when the playing stops again.

“Was that any better?” I’m asking because I forgot to listen, but she hears it as criticism and plays again. I walk to the kitchen for the dustpan.

Gretchen’s mother steps over the tiny demolition and sighs.

“I have a favor to ask you,” she says, pinning her hair while she talks. Oh god. I think. She wants to take a bath.

She asks me to drive her teenage son to an orthodontist appointment.

“No,” I say, and sigh back.

◊

“Now just let me talk for a minute,” BillDean says, interrupting his own monologue. “It’s important that you understand what old BillDean is thinking when he plays.”

I count backward from ten before standing. I can see the lowest two risers. Pitted, raw wood. “Did you get my email?” I lie.

“I don’t read goddamned email.”

“No? About the rate increase?”

◊

I pull carpet all evening. I’m wearing the asshole’s work gloves and using his vice grips. I took his toolbox when I left him. Traded, really. He got my wedding gown, which I assume he’s found by now. I hung it in his closet on my way out.

◊

I don’t know what percentage of Bumble men use fake names, but I suspect the number is high. Mr. Love just wants someone to listen to him. Big Daddy gets “way too excited about God.” Sometimes the fake names are too explicit, forcing Bumble to moderate the information. These men are renamed, aptly, as “Moderated.” Moderated, 54 is “brutally honest.” Moderated, 49 is “fluent in sarcasm.” Moderated, 53 “isn’t angry.” I wonder what he isn’t angry about.

◊

The carpeting on the third stair is impossibly stuck. It’s affixed by something called a tack strip, which I hadn’t encountered yet. I pry it up with a butter knife, but the removal leaves a deep trench in the wood.

“Wood filler,” my sister says.

“Maybe,” I say. “There should be a name for that heavy feeling, ya know?” I cradle the phone, tipping the omelet pan, watching the egg turn white.

“What feeling?”

“You know, that feeling you have where you’re grief-stricken, but you just propel yourself forward anyway? I bet the Germans have a word for it. One of those multisyllabic compound words. Google it.”

“German words for complex emotions,” she says. I can hear her typing. “I see leibeskummer, but—”

“What’s it mean?”

“Translates to ‘lovesickness.’ ”

“Gross. No. Needs more grief.”

“‘Grief,’ ” she says slowly. We’ve got Trauer.”

“Okay, but add the dragging around.”

“She laughs. ‘Perseverance.’ Beharren.”

Okay. Smash them together.

“Beharrentrauer?”

“Yeah. Closer.”

◊

The students are asking where my husband is. Not that they typically saw him during their lessons. Maybe they’ve noticed that my wedding band is gone, or spotted the indentation it’s left. Or maybe the timing of the questions is coincidental. Regardless, it’s the fourth time this week I’ve felt ashamed to be single, and I’m pretty sure this makes me a terrible feminist.

Three students ask if I “live alone.”

“Live alone now?” one says.

“Where’s your husband?” one blurts.

I should say, “I don’t have a husband,” or, “Open your music.”

Instead, I say, “He’s at work.”

◊

Owen is dropped off by a sitter today. It is date night for his parents.

Mabel and her brother are staying with an aunt. Their parents are on a cruise. BillDean tells me that he and Hildy have been married for fifty-two years.

This makes me exactly half as lovable as BillDean, mathematically speaking.

Therapy Keith says your worth isn’t wrapped up in another’s perception of you. But his need to say it suggests a lot of people believe otherwise.

◊

I have eleven new likes this morning. One especially torpid-looking man dates only “fit” women.

“How fit?” I type, clicking past a photo of him, his left hand deep in a bag of Funyuns. “Like, how far would I need to be able to run? Is there a distance or pace I should train toward?”

He asks for a full-length picture.

I send a photo of Emily Blunt.

◊

AlligatorBoots closes his profile paragraph with an apology: “Unable to send pictures of p3ni$. Camera lacks wide-angle lens.”

◊

I assign Mabel a beautiful arrangement of “Greensleeves.”

“Some people think Henry the Eighth wrote the tune,” I say, but then wonder how accurate this is.

“Divorced, beheaded, died,” she begins.

She’s right. We substitute “Carol of the Bells.”

“Set your right hand to autopilot,” I call from the front hall, looking up the staircase. “Because it’s just the same four notes over and over. And the best part?” I say, picking up the carpet’s edge and yanking. “You get to clamp the pedal down. B-flat, third finger, and right foot on the pedal. Keep your heel down and go for it.”

I know more about the other woman than I want to admit. I know from him that she’s the youngest child of a single mom. I know she grew up in Pensacola and spent her summers on the beach.

I fold the carpet under and tighten his vice grips.

Hark how the bells

Sweet silver bells

“Yes on the notes,” I call. “But no to your rhythm. Two eighths in the middle. Think long-short-short-long.

She carries on. By repetition four, it’s improving.

I know she carries Cheez-Its in her purse. Is addicted to ChapStick.

“Yes, but how many measures, Mabel? Count the bars before your left hand comes in.”

“Eight?”

“Good. Start again?”

The scar on her neck is from a dog bite, and she didn’t even have the dog put down. That’s how he always put it. Didn’t even have the dog put down.

The fourth stair releases with a pop. I reach for my butter knife to pry up the tack strip. She rode horses as a kid. Crushed on her middle school band director. Loves Gilmore Girls.

Christmas is here.

Bringing good cheer

To young and old

Meek and the bold

“Wow, yes,” I call. “Start again, but soft pedal with your left foot this time. Let it off in measure five and build.”

Except for a missing E-flat, she’s error free.

Her curtain bangs were his idea. So was finishing her doctorate. “One of the most talented up-and-comers in the field.”

“Ambitious,” he called her.

Merry Merry Merry Merry Christmas

Merry Merry Merry Merry Christmas

Mabel’s scale passage is halting, but every note is there.

“Thumb under on the G.”

I set down the knife, clamping his vice.

She plays the passage again, then again. It’s almost fluid.

“Now from the beginning,” I say, removing his gloves and descending the stairs.

I listen from my chair and smile when she’s done. She’s on her way. The piece just needs continuity now—the kind that organizes small moments into something bigger.

“Long lines, okay?” I say.

She nods.

I tuck her copy of “Carol of the Bells” into her spiral notebook and scrawl “you’ve got this” across the top.

◊

I pull carpet all evening, first with his gloves, then without. I don’t know when he started bringing her home in his mind, but I see now that she was there. In the mornings when he packed the Lean Cuisines. In the evenings on his walks. She sat with us at dinner. She watched him barely eat. And in those lapses when he hardly spoke, so lost in thought, I know now that he was speaking to her. She was with him when he couldn’t sit still and when he worked too long, even from our sofa, and somehow, in his duplicitous state, she was in his mind when he fell asleep with his head on my lap, the last night I ever saw him. Maybe she was in his mind when he handed me coffee or ate lunch from the red-lidded Pyrex. Maybe she stood with him while he cleaned the kitchen, shooing me toward the piano.

I worked my way to the top of the staircase today. Below me, Mabel played her “Carol of the Bells.” It’s cohesive now, a proper narrative, and she knows it.

“Well?” I said, catching her eye as I dragged the carpet out the door.

“Good,” she said. “I’m playing lines.”

And not segments.

You Know Nothing: Stories

You Know Nothing: Stories Yasmina Din Madden

Yasmina Din Madden

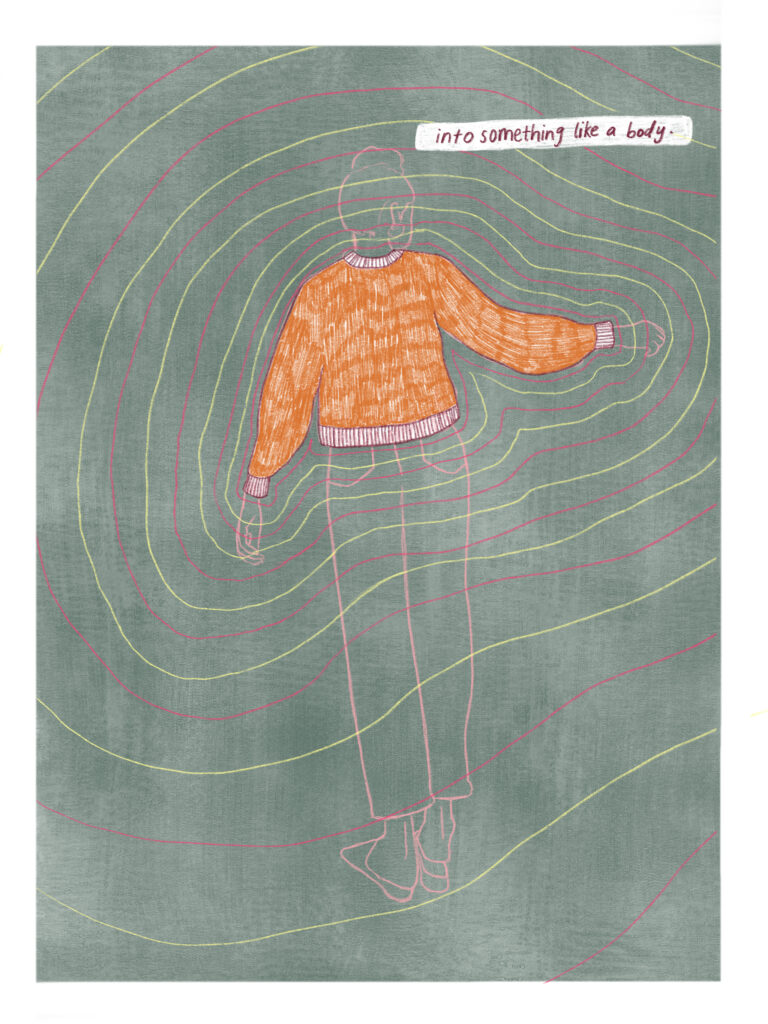

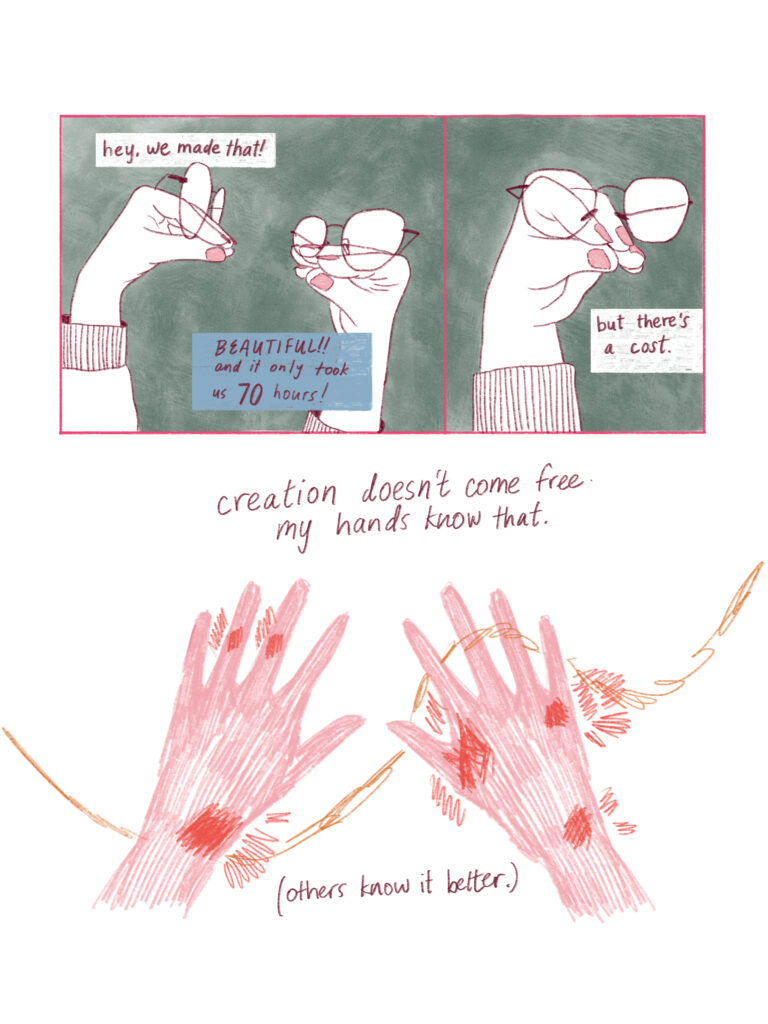

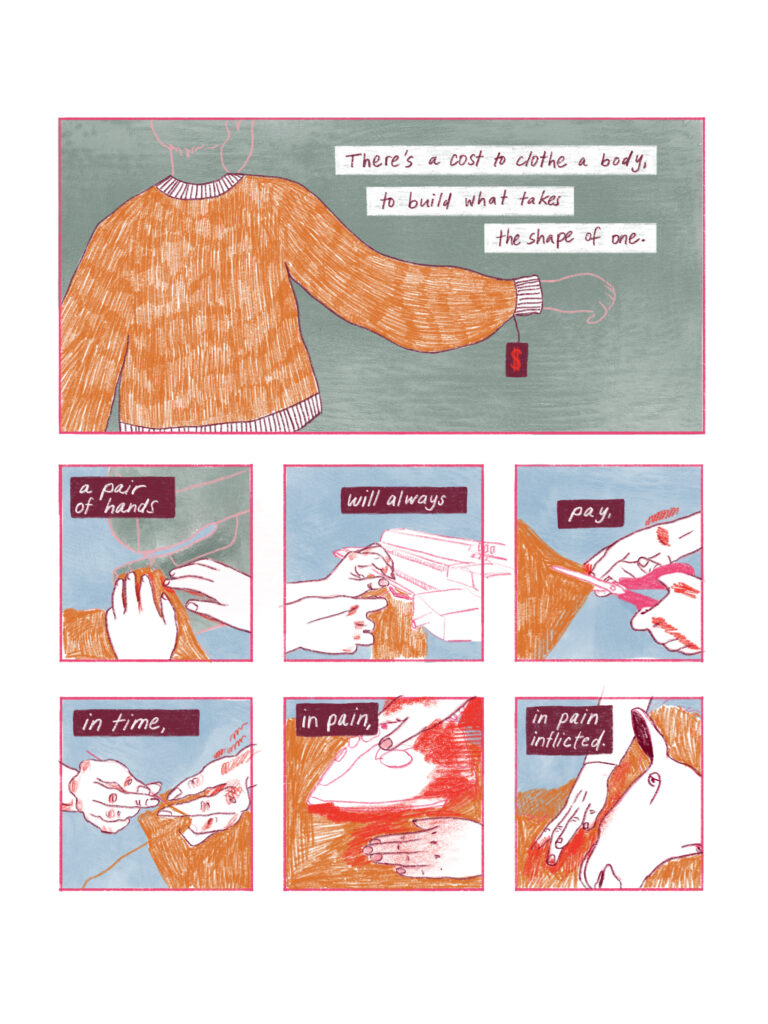

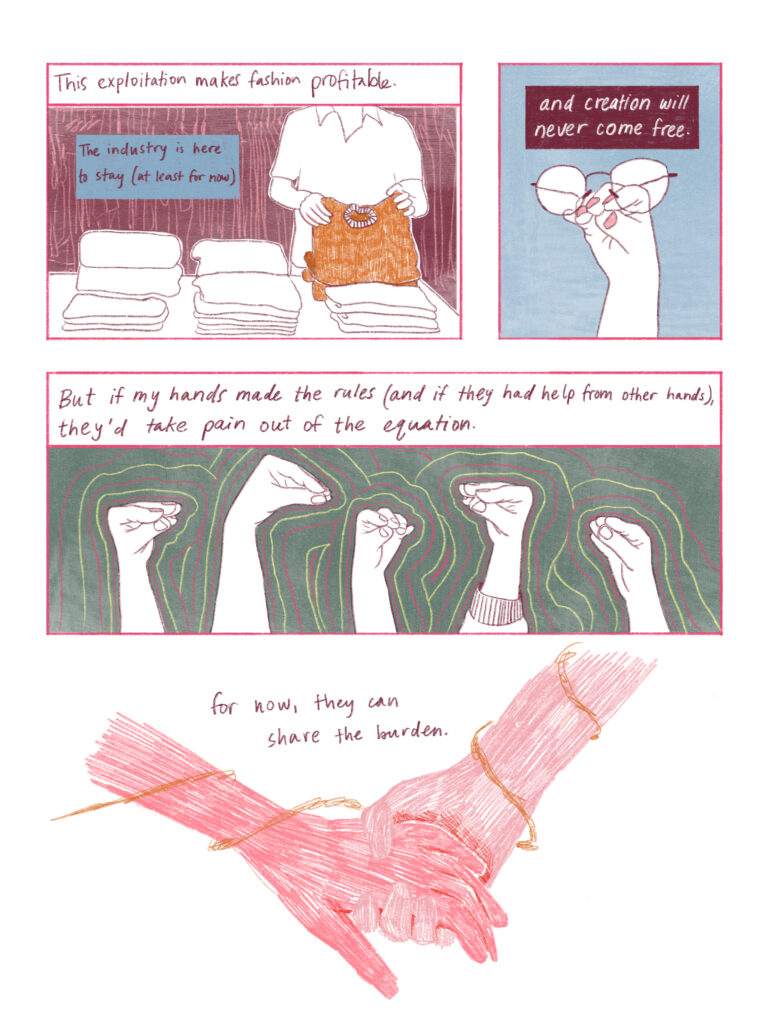

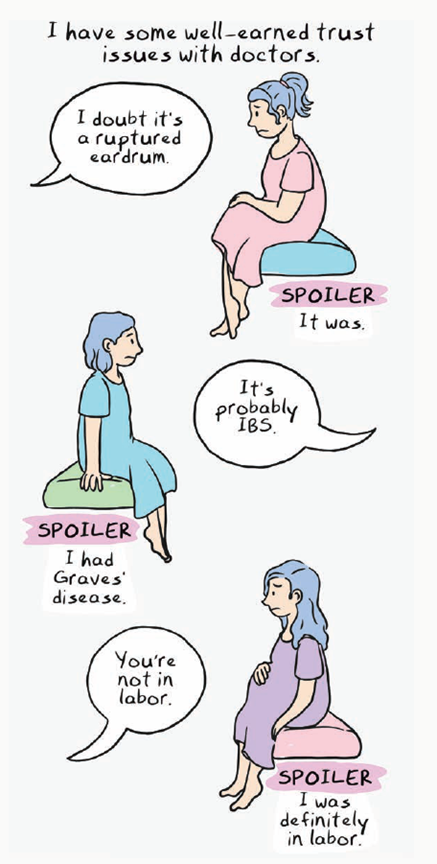

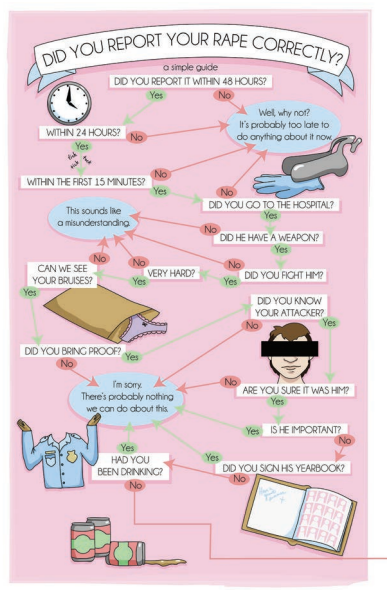

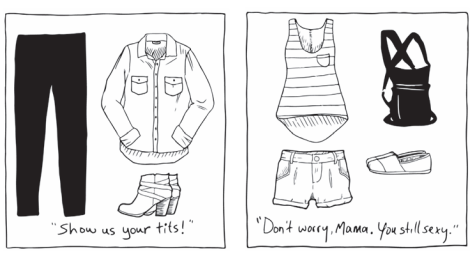

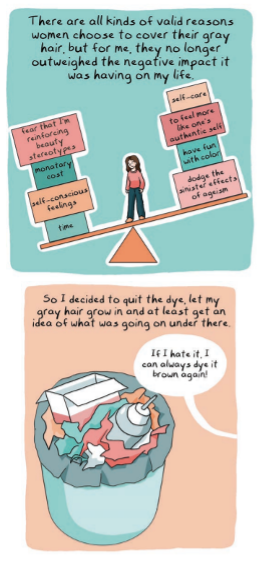

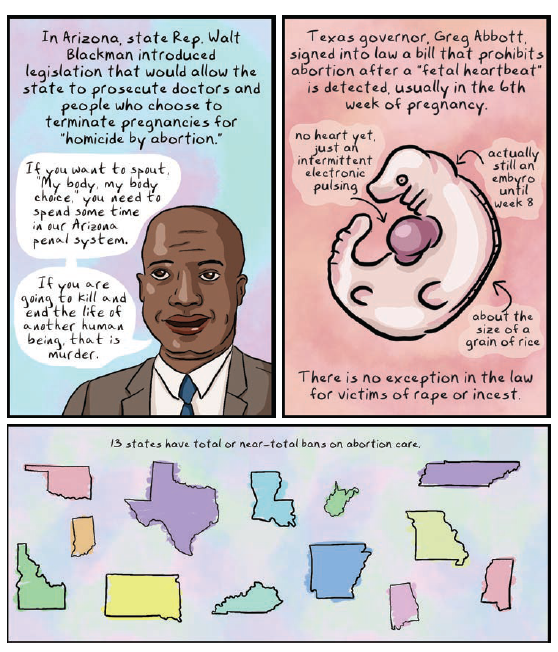

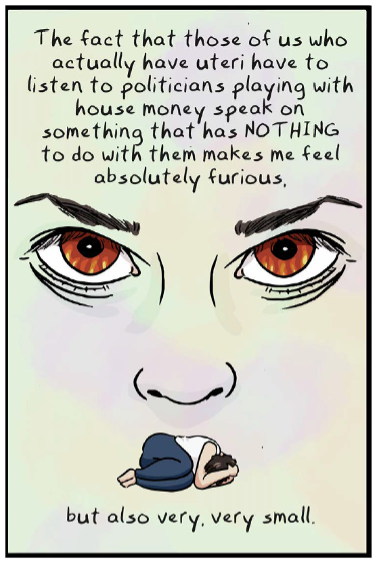

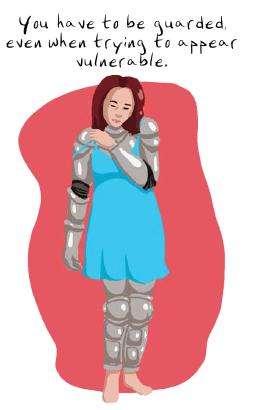

Graphic Rage, by Aubrey Hirsch

Graphic Rage, by Aubrey Hirsch

Lost in the Forest of Mechanical Birds

Lost in the Forest of Mechanical Birds Christian Moody

Christian Moody

The Shah of Texas

Charlie Green

Gold Wake Press

$24.95

2025

The Shah of Texas

Charlie Green

Gold Wake Press

$24.95

2025

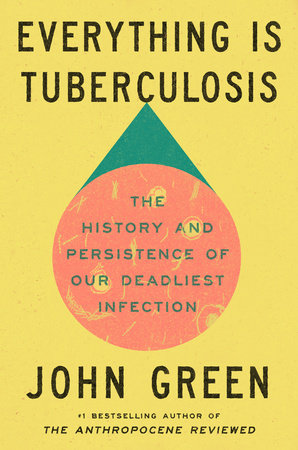

Review of: Everything Is Tuberculosis, by John Green; Crash Course Books; $28.00; 208 pages; March 18, 2025

Review of: Everything Is Tuberculosis, by John Green; Crash Course Books; $28.00; 208 pages; March 18, 2025

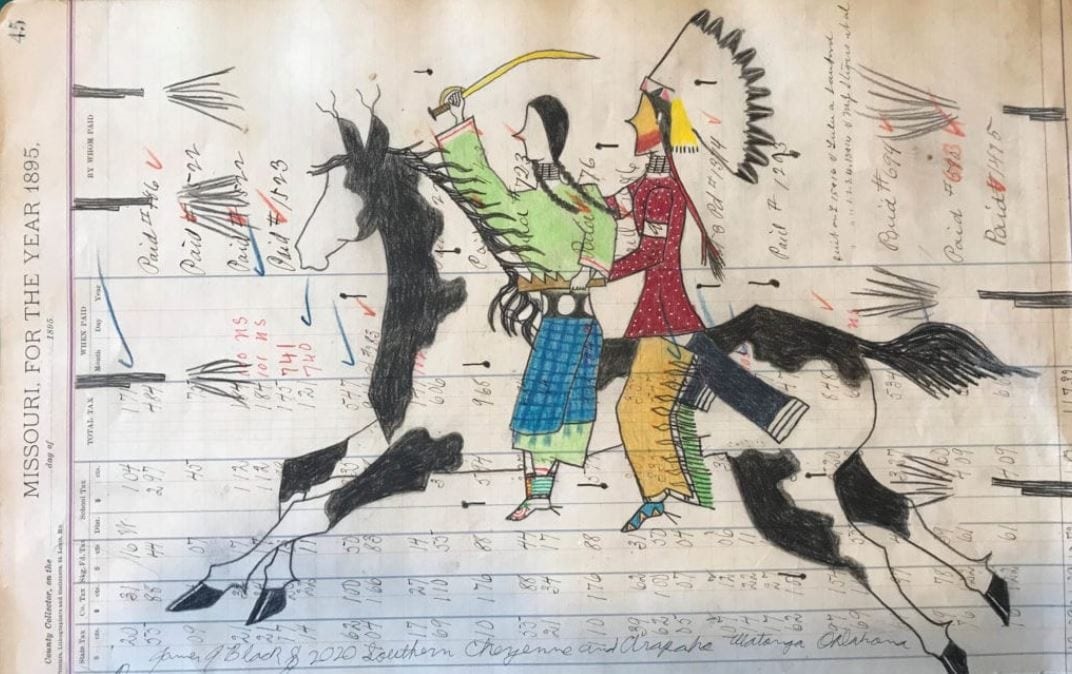

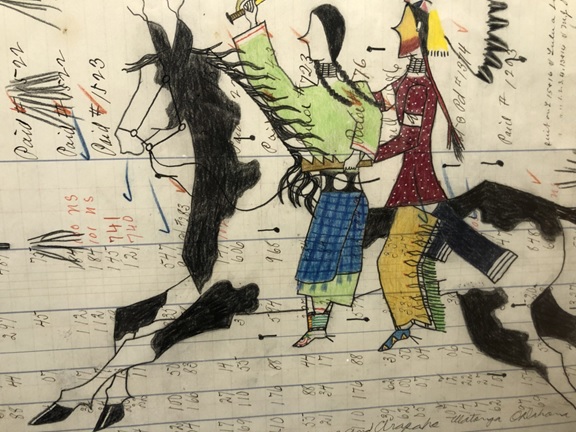

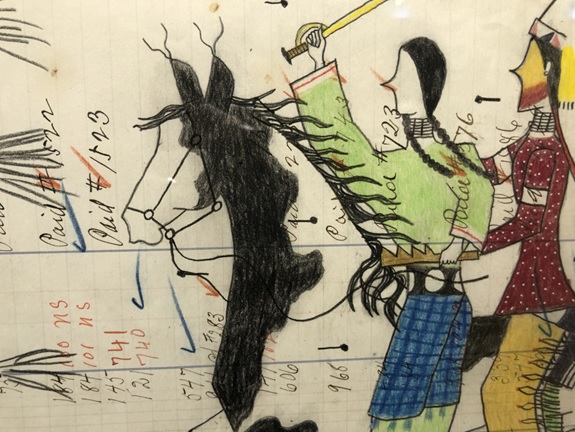

James Black

James Black Shann Ray

Shann Ray

Julian’s Debut

Julian’s Debut