Outside the window, rain obscured everything except the towering eucalypt. The tree was home to a pair of hawks and Janelle hoped they weren’t getting pummeled by the storm. At times, she wished she could be like them, that she could sprout wings and fly away, if only for a while. She sipped her tea and struggled to collect her thoughts; lately, her psyche seemed split, her entire being ungrounded. She longed for answers that proved elusive. Sometimes, bad things happened and there could be no explaining why.

Janelle drained her cup and placed it in the sink along with last night’s dishes. Evidently, if she didn’t do them, then they didn’t get done. But there was no point raising the issue with Brian; she needed to pick her battles, to save energy.

Almost a year had passed since the incident that marked their son’s drastic and seemingly irrevocable changes, and still the doctors had no idea what was going on. Various terms had been mentioned in an attempt to identify his condition—Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Altered Mental Status, Elective Mutism. They could call it whatever they liked, it made no difference—so far nobody had managed to get Jeffery to speak again.

Not even her, his mother.

Shards of rain continued to strike the window. Outside, the eucalypt swayed; leaf litter scurried across the ground, hurled about by the wind, without free will. Was she any different?

Janelle’s husband entered the kitchen and she turned to see him making coffee.

‘You taking Jeffery to the psychiatrist today?’ Brian asked.

‘No, I thought I’d palm that job off to my assistant.’

He looked at her, teaspoon held in mid-air. ‘Everything okay?’

‘Not really. I’d like you to come with us for a change.’

‘I can’t, got a huge day at work. Two open houses and a couple of contracts on the table.’

‘It wouldn’t hurt you to be a little more involved.’

‘Involved?’

A flush of pink crept up Brian’s neck and Janelle experienced a jab of satisfaction upon realising her words had wounded him.

‘Is that what you think? That I’m not involved?’

‘Even Doctor Berwick said she hasn’t seen you in a while.’

‘When did she say that?’

‘Last time we saw her—a couple of weeks ago.’

He took a mouthful of coffee. ‘Well, somebody has to go to work around here.’

‘Excuse me?’

Brian held up a hand. ‘That came out wrong.’

‘It’s impossible for me to work right now.’

‘I know.’

‘Then why bring it up?’

He put down his cup. ‘We need an income, Janelle.’

‘I’d just like you to come to an appointment every now and then. Is that so much to ask?’

They stared at one another.

‘Sorry, but I’ve got to go.’ He retrieved his keys from the hook beside the pantry and disappeared into the hallway.

‘Of course you do,’ she called. ‘And go to hell while you’re at it.’

The front door slammed and she soon heard his car rumbling down the road.

Janelle turned to look outside once more. From where it stood battling the elements, the eucalypt appeared to observe her.

‘What are you staring at?’ she asked.

Its branches swirled on with admirable forbearance. Or was it disappointment?

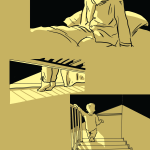

At first, he simply drew around the sides of a piece of paper—a wolf’s face here, a doodle there—but after a while, he began to write.

.jpg)

He read over the letter, then screwed it up and threw it into the little bin beside his desk. It was baby-ish to write about the noise inside his head. Stupid.

Jeffery stood, walked to the window and looked outside. He wanted to run around in the rain and let it wash the bad memories away. If only the wolf-men would leave him alone.

Doctor Berwick had brought a colleague into their session—one Professor Lycan from the Institute of Psychological Studies, who was apparently researching “unusual” psychological childhood conditions. Janelle wished Doctor Berwick had sought her permission to have this man present. Even a little warning would have been nice. She didn’t like the idea of Jeffery being observed by someone she didn’t know.

The professor’s hair, along with his neat beard, was gray-white. He wore round, steel-framed spectacles and sat scribbling in a notebook that rested against his legs. The sound of his pen running across paper seemed to fill the room. So far, he had said very little.

Jeffery stared at his shoes. Janelle could feel the tension emanating from his little body. She wondered if the doctors felt it too. Probably not. They weren’t attuned to him the way she was.

‘And there’s been no change in his behaviour?’ Doctor Berwick was saying. ‘No indication he’d like to interact more?’

‘Not particularly,’ Janelle said.

‘He’s still doing his drawings?’

‘Yes. ’

‘That’s good.’ Doctor Berwick glanced at Professor Lycan, who continued to write with feverish intensity. ‘It’s vital that he has a creative outlet, somewhere to express his feelings, so to speak.’

The professor looked up from his notebook. ‘Mrs Watson—’

‘Please, call me Janelle.’

‘Alright, Janelle—Jeffery is twelve years old, correct?’

‘Yes.’

‘And how would you describe your relationship?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Would you describe Jeffery’s attachment to you as positive?’

She tilted her head. ‘Of course.’

‘What about the relationship with his father?’

‘Brian works full-time, but when he’s home they get along well. Why do you ask?’

The professor placed his writing materials on a nearby desk. ‘Studies have shown that parents of behaviourally inhibited children often perceive them as vulnerable. Such perceptions can influence how they engage with their children.’

‘How so?’

‘For instance, parents who regard their children as socially withdrawn often endorse practices that discourage independence and exploration.’

Janelle held the professor’s spectacled gaze.

A clock on the wall ticked.

‘Are you suggesting my husband and I are overprotective?’ she asked finally.

‘I’m sure the professor is simply trying to get an idea of Jeffery’s life at home,’ Doctor Berwick said.

‘His life at home is fine. I take it, Professor, you’re aware of the incident my son and I witnessed around a year ago?’

‘Doctor Berwick has filled me in on that history, yes.’

‘That history, as you call it, is where the problem lies,’ Janelle said. ‘Before then, he was a content, happy boy. He attended school, enjoyed play-dates with friends. He spoke. But after that day, everything changed.’

‘No doubt there’s significant traumatic residue associated with that event,’ the professor said. ‘But Jeffery needs to realise that what happened is in the past. He needs to make peace with the bogeyman.’

‘The bogeyman?’ Janelle was at a loss as to why the professor would refer to the stuff of folklore and scary night-time stories when discussing her son’s condition. It was 1987, not the Dark Ages. Surely he understood that what Jeffery had seen was terrifyingly real.

‘I think Professor Lycan means we want to create a safe environment in which Jeffery is encouraged to face his fears,’ said Doctor Berwick, ‘to understand that what happened was an extremely unfortunate, one-off event.’

Wasn’t that what she’d been trying to do? To make sure he felt safe? To make sure the goddamn bogeyman didn’t, once again, come in and blow up his world.

‘May I ask Jeffery to do something?’ the professor said.

Janelle crossed her arms. What was she supposed to say? ‘Okay.’

The professor grabbed his pen and notebook and passed them to Jeffery. ‘I believe you like to draw.’

Jeffery nodded.

‘How about you draw whatever comes to mind when you think of that day at the bank. You remember that day, don’t you?’

Another nod and then Jeffery opened the notebook. No one spoke as he tended to the task at hand. Janelle shifted in her seat as the clock on the wall continued to tick.

A few minutes later, Jeffery placed the notebook on the desk and dropped his gaze to the floor.

The professor retrieved his notebook and studied the image. He then handed the notebook to Dr Berwick, who examined it briefly before passing it to Janelle.

There had been two of them: they’d burst into the building screaming orders, shotguns raised, their faces hidden behind strange wolf masks. The first man had hurried towards the counter and started yelling: ‘Everyone get down and don’t move.’

Janelle kept still, her face pressed to the floor. Jeffery lay nearby, eyes pinned open by toothpicks of terror.

‘Open your drawer,’ the first man said. ‘Get the money out. Come on. Put it in the bag. Now.’

‘Okay, okay,’ the attendant said.

‘Come on. Money in. Move it.’

‘I’m trying.’

‘Shut up and move.’

‘I’m going as fast as I can…’ the attendant said, fumbling with the bag, ‘…doing my best.’

‘Christ, shut up. Or you’ll get a bullet in the brain.’

It occurred to Janelle that perhaps she was having a nightmare, that her psyche was drawing upon some movie she’d seen, or a story she’d once read. Maybe it was all just a dream. Just a dream. Just a dream.

‘Sorry,’ the attendant said. ‘This has never happened to me before. I—’

‘You wanna die?’

‘No, no, I don’t.’

‘Then stop talking.’

‘Sure, okay. I just—’

The sound of a gunshot bounced off the walls, reverberating in what was otherwise a terrible and gaping silence.

‘What the hell?’ The second man strode towards the counter. ‘We said nobody shoots.’

The first man answered: ‘You heard him—he wouldn’t shut up.’

‘Jesus! Grab the bag and let’s go.’

Janelle watched Jeffery, who now had his eyes squeezed shut. She would do anything—anything—if only he were kept safe.

The second man began shouting orders: ‘Everybody stay down and no one else gets hurt.’

Before long the men had fled through the building’s front doors, and the horror was over. Or so Janelle thought.

She glanced from Doctor Berwick to the professor and back again. Janelle felt somehow responsible for what she was looking at, for the memory that had scarred Jeffery’s mind. But what could she have done? How could she have possibly foreseen events set to unfold that day?

The professor took the notebook from Janelle and turned to Jeffery. ‘You must have been very scared.’

Jeffery shrugged.

‘Do you see such wolf-men very often?’

He nodded.

‘In your mind?’ The professor pointed to his temple. ‘In your dreams?’

Another nod.

‘Sometimes I have bad dreams, too—everyone does.’

‘It’s not from a dream,’ Janelle said. ‘The men were wearing wolf masks.’

The professor continued to focus on Jeffery. ‘Well, you know what?’

Naturally, Jeffery didn’t answer.

‘Those bad men aren’t coming back,’ the professor said. ‘They’re in prison and they’ll be there for a very long time.’

Janelle was certain the offenders had never been apprehended. What, exactly, was the professor up to? ‘I think Jeffery’s had enough for today.’

The professor stared at her. For a moment, she thought he would insist upon having them stay, so he could continue studying them as he might have studied curiosities at a freak show.

Instead, he said, ‘It’s been a pleasure to meet you both. I hope we can talk again.’

She rose to her feet. ‘Come on, Jeffery. It’s time to go.’

‘Thanks for coming in.’ Doctor Berwick stood and clasped her hands together. ‘Be sure to make another appointment, won’t you.’

Janelle kept quiet as she led her son from the room. Who would they turn to now?

By the time they arrived home, the day had cleared. After lunch, Janelle took Jeffery outside. There was a pond in the back garden and he enjoyed playing near its edges. As they approached the eucalypt, she spotted something on the ground—a nest, and beside it an empty egg. She wondered about the baby bird and scanned the tree, but saw only leaves and branches. Jeffery squatted down to survey the damage.

After a while, he looked up at her. He seemed neither upset, nor surprised, by what they’d found. Janelle took him by the hand and they continued on.

When they reached the lake’s edge, Jeffery crouched to inspect the water. He’d linger there for hours given the chance, and Janelle would have been happy to let him. Truth be told, she dreaded her husband’s return from work every day, the forced conversation, the awkward silences. She only ever managed to relax when he wasn’t around. Then again, maybe she really had become selfish and difficult, as Brian claimed the other night.

She sat on the garden seat facing the pond. Shafts of golden light shifted upon the water.

As was often the case when she had time to think, Janelle began to mentally list the potential reasons as to why she and Brian had grown apart. To begin with, they hardly had any common interests. Years ago, they’d enjoyed sailing—that was how they’d met—but the hobby fell by the wayside after Jeffery came along. Their financial situation certainly didn’t help; the real estate agency had been struggling for months and money was tight. Then there was Jeffery’s refusal to speak, which had been a tremendous strain on them both. And yet, he wasn’t to blame for their problems; he was just a scared, young boy who’d been damaged by the world.

In any event, it seemed neither she nor Brian had the courage to voice the truth: their marriage was in trouble. It was easier, she suspected, for them to pretend that the benefits of their relationship outweighed the drawbacks. Besides, they needed to consider Jeffery; keeping their homelife on a relatively even keel was essential to his wellbeing. She watched as he skimmed stones across the lake’s glassy surface. She had failed once to protect him, but wouldn’t do so again. Not if she could help it.

Later, as they walked to the house, Janelle again inspected the eucalypt. There was still no sign of the hawks.

Janelle placed their meals on the dining table before pouring them each a glass of water. Jeffery gave a smile, which she knew was his way of saying thank you. Brian continued to scan the real estate section of the newspaper. She sighed, but he gave no sign of having noticed.

She sat and began to eat. Janelle had experimented with a new casserole. The recipe promised to deliver “a knock-out punch of flavor”, but she thought it tasted bland. Then again, maybe the problem rested with her. Perhaps she had lost the capacity to enjoy anything.

At last, Brian put down his newspaper. ‘How did it go today?’

For some reason that she couldn’t identify, Janelle felt the need to make her husband work to deliver meaning. ‘How did what go?’

‘Jeffery’s appointment?’

‘It went smashingly well. Thanks for asking.’

Brian thumped the table, making Jeffery flinch. ‘What’s gotten into you?’

‘I don’t know what you mean.’

‘Yes you do. I can’t do a thing right these days. It’s as if my very presence offends you.’

Janelle realised this was quite possibly true—maybe she couldn’t stand being around her husband anymore. She began to clear their plates. ‘Actually, your presence would have been very much appreciated today.’

He leant back in his chair and stared at the ceiling. ‘I want you to be happy—I want us to be happy—but I don’t know what to do. I don’t know how to fix things.’

Janelle couldn’t think of a response. She knew Brian was trying to move forward, to take a step in terms of bridging the yawning rift that stretched between them, yet her instinctive reaction had been to freeze. She seemed unable to reconnect on any level. Perhaps she’d become accustomed to their dysfunction, maybe even addicted to it.

In any event, the moment passed.

‘I work hard to pay the bills,’ he said, ‘to keep a roof over our heads—’

Janelle returned to the table. ‘Oh, that’s right, I don’t work.’

And there it was—the relentless merry-go-round of hurtful misunderstandings and accusations that swept them up in its momentum, again and again.

‘I never said that.’

‘But it’s what you meant,’ she said.

‘Why do you always twist my words?’

Jeffery jumped up. ‘Stop,’ he said. ‘Just stop.’

Janelle stared at him, transfixed. It was as if Jeffery were the only person in the room, the only person in the world. His expression, pleading and distraught, swamped her vision. She knew she should say something. Anything. But the shock of hearing him speak had struck her dumb. Slowly, she rose to her feet.

‘Son?’ Brian said.

Jeffery turned and walked away.

Janelle watched his receding form, then met her husband’s gaze. His face was filled with pain…and something else. Relief? Hope?

Moments later, Brian trailed after their son.

She started to follow, then stopped. She needed time to process what had happened.

Janelle crossed the kitchen and peered out the window. Silent and watchful, the eucalypt stood looking in. Upon one of its branches, two small shapes sat huddled together. She watched them for a while and then returned to the table once more.

.jpg)