Anne McGrath’s “Modern Ancestors,” is a series of pieces constructed from mixed materials. See more of Anne’s work on Instagram @TheAnneMcGrath.

Anne McGrath’s “Modern Ancestors,” is a series of pieces constructed from mixed materials. See more of Anne’s work on Instagram @TheAnneMcGrath.

Catherine-Esther Cowie, Heirloom, Mixed Media Collage

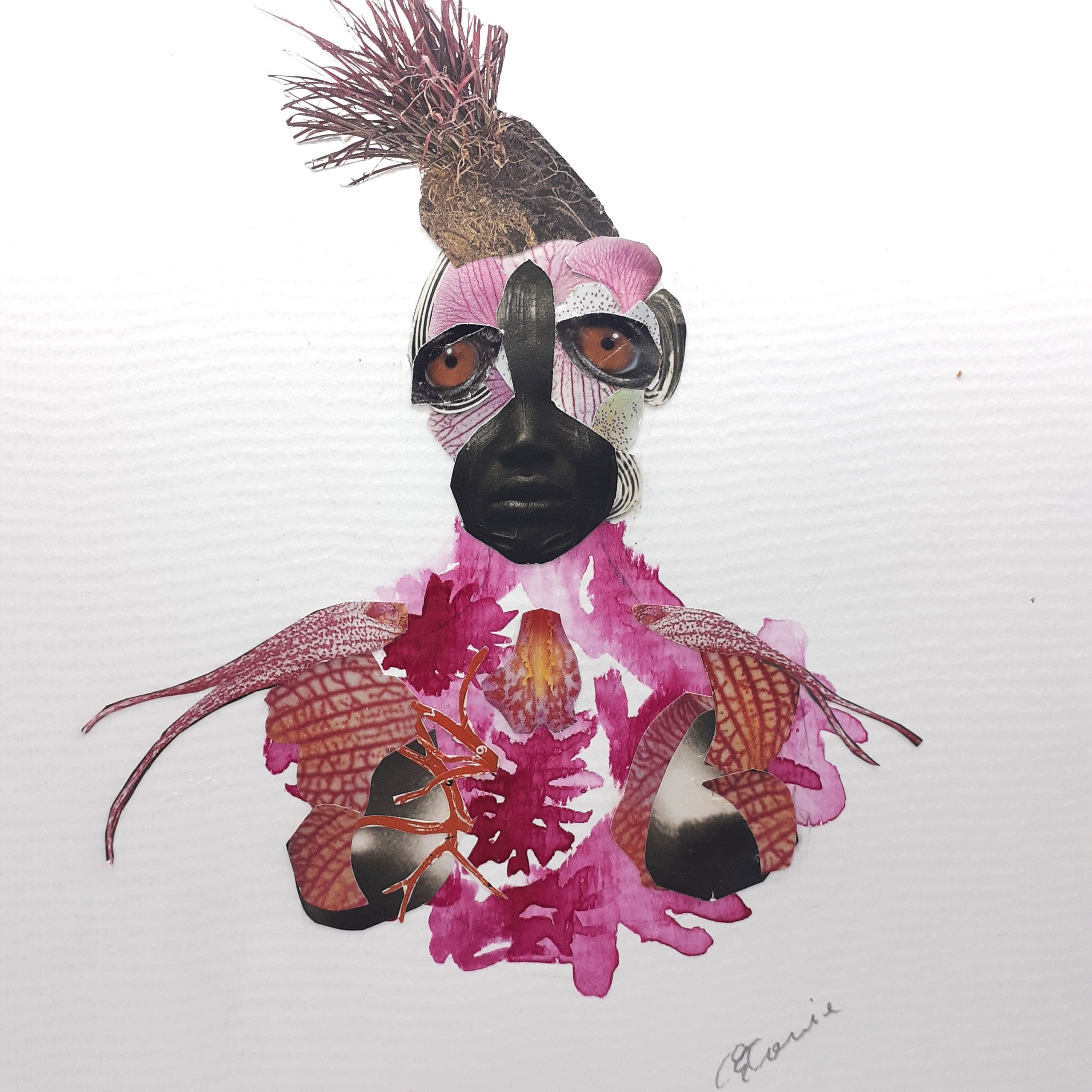

Catherine-Esther Cowie, Auntie G. My Dahomey. My Amazon., Mixed Media Collage

Catherine-Esther Cowie, Hello Again, Blès, Mixed Media Collage

Catherine-Esther Cowie, The Queen of All the Dirt, Mixed Media Collage

I work in collage for its accessibility, for its infinite possibilities beyond working solely in paper but incorporating ink, watercolor, textiles and 3D elements. This series features cut-outs from fashion magazines, images of orchids and magenta India ink. I seek to map the emotional landscapes of my subject matter, women, immigrant women, Caribbean women and the complexity of emotions/states that simultaneously exist: shame and pleasure, loss and strength, beauty and ugliness.

The portraits in this series began as a form of play: I wanted to see how paper and ink could work together. They represent fears, griefs, memories, self-perceptions etc. The piece titled, “Hello Again, Blès” explores how I experience trauma. A sneaky buried wound…then a trigger…through a body now. “Blès” means internal wound in St. Lucian Kwéyòl.

Naming this collection “Heirloom” gestures to a writing project that I am working on that explores what we pass on or give to another generation: ruin and/or redemption. What was carried in the bodies of my mothers: their fears, trauma, loves, afflictions, histories. How some of it is transmitted through story, through their bodies— their way of moving and being in the world. These portraits explore what I carry around in my body…what I may or may not pass on…

Rachel Poliquin, in her 2012 book The Breathless Zoo, writes that “Taxidermy is deeply marked by human longing,” revealing our hopes and dreams about our place in the natural world. Natural history dioramas present a carefully constructed, perfectly encapsulated and controlled experience of nature, revealing as much about humanity as the nature depicted. In Broken Models, Steensma Hoag negotiates access to dioramas in various stages of being decommissioned and uses these fictional spaces to create imaginary scenes. By introducing a worker wearing a white Hazmat suit, which evokes images of advanced technology labs in which the environment needs to be protected from the worker, the series suggests a scientific method of understanding and quantifying our experience of nature and comments on our failed construction of the environment as an inexhaustible resource.

This series features small, improvisational, origami-like collage forms created from manipulated pieces of encaustic-infused rice and tissue papers. The series began with the otherwise practical intention of reusing scrap materials but has evolved into something more meaningful and representative of an interest in science, nature, memory, and narratives of ecosystems in flux. These abstract compositions are the result of an exploration of how encaustic-infused paper can be manipulated through layering, cutting, folding and the use of heated tools. My goal is for these non-representational compositions to reflect a suspended state of evolution as one form shifts to become another.

This body of work is inspired by the non-profit organization, Legacies of War, and their mission: “To raise awareness about the history of the Vietnam War-era bombing in Laos and advocate for the clearance of unexploded bombs.” As a refugee/immigrant, the process of connecting and disconnecting with a place or community are abstracted ideas of migration. Similarly, the collage and painting process is unpredictable and is an ongoing dialogue about assimilating and relocating into another culture and space.

The Production Landscape series profiles the path of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) in North Dakota, one of the four states it crosses. For people like me who grew up in suburbia, massive infrastructure projects such as the Dakota Access Pipeline are abstractions. I benefit from the resources they transport, but the costs of such delivery systems are born by others in far away “fly over” places. Beginning in Fall 2016 I followed the pipeline route in North Dakota and photographed the landscapes it traversed. I wanted to see what construction looked like from the ground and view the range and agricultural landscapes reshaped by its insertion. The project does not attempt a comprehensive documentation of the pipeline route or the Bakken-producing region from which the oil is generated, but rather seeks to add context to an important public discussion about natural resource usage. The images highlight the physical disruption of the land’s surface and show the rural areas impacted by its construction. In doing so, the series explores the ways in which landscape photography contextualized current debates related to land-use and natural resource extraction.

These paintings, which attempt to describe the complexity of structures, serve as psychological portraits of the people of Baltimore, Maryland, and Nagasaki, Japan. Boarded up doors and windows trap the dark secrets of these poor dwellings. Degraded humans and distraught ghosts wander through these dark places. Inferences to the human psyche are enmeshed in each gash, hole, and sloppy patch.

This series of photographs examines the abandoned prison cells of Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The Penitentiary subscribed to a theory of rehabilitation that proscribed confinement and a lack of interaction with other inmates. This ran counter to the prevailing system in the United States at the time where harsh physical punishment was the norm. Ideas of church and religious experience are embodied in the building and served as a guide for how prisoners should be rehabilitated: hallways looked like that of a church; low doorways required one to bow and seek penance from a greater power; and a single small skylight, acting as the “eye of God” lit each cell.