March 12th

Most evenings I go for a short walk around the neighborhood, my route always the same. I take a right on 1st, another right on S Street, uphill three blocks to where it Ts with 4th, east two blocks on 4th along the Calvary Cemetery, then back to 1st via U Street. Last night was my first walk since Bree’s death, and I wondered: why such a cemetery-centric route? My route could just as easily rectangle or staircase south towards Reservoir Park, where students from the U play Frisbee and parents admire their kids from playground benches.

Here’s how Wikipedia describes the grid I call home: “First surveyed in the 1850s, the Avenues became Salt Lake City’s first neighborhood. Today, the Avenues neighborhood is generally considered younger, more progressive, and somewhat ‘artsy’ when compared to other neighborhoods. Many young professionals choose to live there due to the culture and easy commute to downtown. It is also one of the most important strongholds of the Democratic political party in Utah.”

I used to think about death constantly—that was during my religious teens… I was going to insert a quotation from the Bible here, something along the lines of “Always keep in mind your last days, and you will never sin,” but those memories are so distant and the internet is so choked with sin and warnings about sin that even Google’s divine algorithm is powerless to help me find the verse. I saw my classmates doing what teenagers do, and I couldn’t believe they could just ignore the punishment in store. Even if they didn’t believe—wouldn’t they at least be wise enough to acknowledge the chance that the fire was real and gamble on the side of avoiding it? As those fears gradually then suddenly receded, as I realized that disbelief could be active rather than passive, I experienced an unexpected side effect: my new certainty that everything would go black when I died alleviated my fear of death rather than intensifying it. There was nothing I could do about its inevitability, so it wasn’t worth thinking about. And at least there was no punishment in store.

Even these brief thoughts risk flashbacks I’d rather avoid—I admit I wouldn’t be recording them if not for my employer-prescribed grief therapist’s insistence. Or that neglecting to do so would suggest that I’ve inadequately grieved my daughter’s death. I keep myself very busy, and I’m not sure that time off work is really going to be beneficial. I haven’t had time just to sit and think in years—and that has suited me fine.

During my walk yesterday evening, I noticed for the first time the abundance of crack sealant on 4th. The other roads in the Aves are not so heavily sealed (I had to check), making me wonder if 4th is more heavily or less heavily trafficked, better kept up or worse. I took these pictures today.

Some metaphor was nagging my mind, the sealant as intestinal or labyrinthine, but it escaped my articulation until I passed by T street and saw painted on the asphalt what I momentarily mistook for graffiti. Since I couldn’t read it, I found myself tilting my head, then walking around the graffiti so that it would be north of me, thus, said my logic, legible. Strange logic since the Aves reads bottom to top, 1st being the southernmost street, a grid radiating outward from Temple Square.

What appeared to be ornate black writing highlighted in white turned out simply to be the coincidental crossing of street sealant with the strip of white paint notifying drivers where to stop for the stop sign.

Writing, it occurred to me. The street sealant is just like a type of writing.

I mean, the white line is certainly a type of writing. Although I don’t think I’d ever consciously acknowledged this feature of roads’ communication with drivers, it says “Stop here” just the same as the white letters on the red octagon. I looked at the black sealant lines more closely.

The beginning was a mess, a snarl of capital Rs and As and Ys. Then a sort of W or M, a cursive R and the number one. A zero with a slash through it (Greek phi or theta), a T, an A, a P. Trailing off into maybe a Z at the end.

No, these marks are meaningless flukes. It’s not much like writing. Not like the actual graffiti I discovered on my fence returning home.

MOST timid tagger in the city. I think I’ll leave it there.

I think my anxiety over starting this journal, of writing something for the first time since a college creative writing class, something that doesn’t have to do with projecting city water supply, must just be causing me to see writing everywhere. Not just the names on tombstones, which—for the first time in all my walks—were those of human beings, not just those dashed dates that were the most different of all the days McNeil or Duddshuh or VanWaggoner called their lives, not just the giant U on the side of the hill that here could stand for University or Utah or Utes… The power lines themselves seemed to sag and crackle with communication that only my dimness kept me from deciphering.

Today I got a few strange looks for photographing the asphalt, particularly because I have a dumbphone and the only camera I own is a video camera that also takes stills.

March 13th

Last night, my route was disrupted by the presence of a stranger headed north on U Street. My feet just started following him. Along the eastern edge of the cemetery, I tried to stay far enough back that I wouldn’t arouse suspicion, but close enough that I might get a look at his face when he passed under the streetlights. I wanted a face to paste on my absurd fantasy. There was no reason for my heart to be pounding so hard, for me to feel the thrill of the hunt. He entered a house and was greeted, I saw through the window, by a kitchen-full of twentysomethings holding cans of beer. Hanging back, I wondered what the reaction would be if I knocked on the door, asked if it was an open party. I had never visited this section of the Aves by foot.

March 14th

I set out again last night searching the dark streets for Bree’s lover. It’s crude to think this way—my daughter’s death as a liaison—but my mind ignores all pleas of decency.

I know that my chances of encountering Bree’s lover are slim, but it wouldn’t be the most remarkable coincidence this month. I brought along my camera even though I’m not sure if it would work in the dark or what I’d do if it did. My ears were even more alert than my eyes, filtering the night’s noise for a sound that’s familiar even though I can’t remember ever having heard it. Suctionless unstoppering. Metal that’s heavy.

As I walked by the cemetery on 4th, I noticed a little neon light that someone had used to decorate a loved one’s headstone. It was a meager flare in the night: red to purple to blue to green to yellow to red to purple to green to yellow to red to purple to… A depressing sort of vigil, and I found myself thinking: if I’m to be remembered thus, I’d rather be forgotten. Regarding my cremated remains, my instructions will be Dump wherever. I’ve always liked Zion National Park and could see my ashes borne from the peak of Angel’s Landing. But it’s such a popular destination that there’d be people all around who’d get bummed out. Also—I thought before realizing the thought’s absurdity—I’m afraid of heights.

Above the cemetery, the letter U luminescent on a hillside, blinking: red red red red red red red… My mind transformed it into “you.” Zoom out even a miniscule distance (proportional to the cosmos)—the grave’s little light and the bombastic U would be equally invisible.

March 15th

I told Rich in our session today that boredom is not helping with the grieving process, and he suggested that I take up a hobby or two. We decided on Nintendo and piano, both of which have been sitting inactive in the house since Bree’s death. I used to play piano, but I never really got into video games. Also, whereas the musical instrument is unchanged since the last time I’d played it (and for two centuries or so before that), the new WiiU system Bree’d brought into the house had evolved into something radically different than the gray console on which I’d last chased a one-up mushroom down a bottomless pit, much to my young daughter’s delight. The hulking controller alone threatened to overwhelm me. It had its own screen, and everywhere I looked there was another button or joystick. The first game I fired up was called ZombiU, not quite the type of therapy Rich would approve of, I’d imagine. It took me hours to get past the game’s intro, a weaponless character fleeing zombies through a subway to get to the “safehouse,” following the instructions of voice that identified itself as “Prepper.”

The safehouse contains 1) a metal locker where you can stow weapons and ammo and health packs that you pick up on your missions across embattled London, 2) a work table where you can add modifications to your weapons, 3) a computer system that provides you with surveillance of the game’s various districts, 4) a generator you have to refill with fuel every so often, 5) a bed where you regenerate as a new character when you die—I find it’s best not to get too attached to any single character, and 6) a manhole cover you lift off to reveal the entrance to the sewers. ZombiU inverts the sewer system into a place of speed and safety, allowing you to warp at loading-speed between the safehouse, Buckingham Palace, Brick Lane Markets, etc. The surface overrun with verminous versions of homo sapiens, the previously proximal space between civilization and its subconscious has become a haven for what traces of humanity remain.

March 16th

The presence on Bree’s desk of this vintage toy:

The goal is to negotiate a ball bearing from the START alcove around a maze of plastic partitions without allowing the ball bearing to fall through holes in the surface that represent a variety of hazards: Haunted Mountains, Black Mountains, Blood Lake, Man Eating Plants, Poison Desert, Tiger Valley, Sargasso Sea, and so on. I spent twenty-three minutes playing it before finally reaching the FINISH. Tucked within that right angle, the ball bearing is away from hazards but doesn’t know what to do with itself. It rests in an infinity of safety and boredom.

March 17th

Today Rich asked how my grief documentation is going, and I told him that I have nothing to write about.

He told me there’s always nothing to write about. I’m not sure how clever he was intending to be.

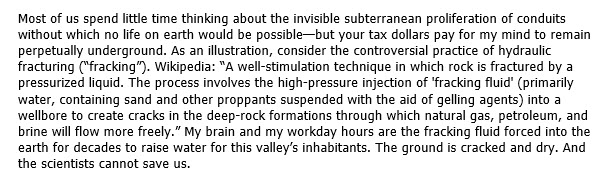

I’m auguring snarls of tar sealant, I told him. I’m stringing Bree’s status updates on telephone lines. I’m reading everything I can find about the Well of Souls.

Not a natural cave per se, but a chamber beneath the Foundation Stone, where Abraham purportedly attempted to sacrifice Isaac and/or Ishmael. But cave-like—but inside–a chamber further interiorized by the Dome of the Rock. Pierced Stone. Wikipedia: “Jewish tradition views it as the spiritual junction of heaven and earth.” I tried curling into a ball in the deepest corner of my unfinished basement, but it isn’t the same.

March 18th

In an effort to learn how to better use the controller’s touchpad to navigate post-apocalyptic London, I stumbled across a ZombiU promo video online that demonstrates the various functions of the touchpad. The hands holding the controller get increasingly twitchy as the three-and-a-half-minute video progresses. The viewer is not sure why. At the video’s conclusion, the arms’ veins and arteries blacken, its flesh molders, and—if that isn’t enough—an off-camera screech testifies the game’s ability to infect those who would dare play it. It’s a clever marketing scheme—and accurate in different ways than I think its creators foresaw.

March 19th

Bree’s birthday. I don’t drink very much except tonight. Made the mistake of going on her Facebook page and scrolling through the birthday wishes and her last posts. In my current disbelief system, the continued persistence of her Facebook and Twitter and Instragram and Pinterest pages are the best approximations of a soul and the afterlife that we can attest to. The first step in the science fiction scenario of being able to upload our consciousnesses and live forever.

I unfriended the friends who wished Bree a happy birthday without realizing that she’d plummeted to a lonely death. Now only 21 people like her “suicide” post, down from the initial 42. Police and logic eventually ruled that her death was not suicide. It was an unlucky night, and sometimes you just happen to vague-book right before you die of incredibly natural causes: Wikipedia is heaven when you don’t want to remember anymore.

Lo, Google informs me I’ve been quoting Bree quoting Nick Cave. Sweep me away for an hour or five, Wikipedia, you means of discovery and forgetting to which I return again and again. Give me discography, give me Murder Ballads, by God give me personal life.

March 21st

One infuriating aspect of the ZombiU is that, when your character dies and you regenerate as another character with another name and former occupation at the safehouse, you lose all of the resources that were in possession of the character who died. That zombified character’s location is marked with a skull on the sewer map, and if you want your weapons and ammo and health packs back, you have to go to that location—now armed only with a cricket paddle, a handgun with six rounds, and whatever you were wise enough to stow in the safehouse’s locker—and kill the character you’d been trying so hard to keep alive. If you die again before doing so, all those supplies are gone.

Discomforting, what comforts us.

Not only does my bedtime get pushed back further and further each night by my urge to meet just one more of the game’s objectives. Just one more, just one more… But the game’s content, graphics, and geography are corrupting my daily perception. I begin grafting the face of Arthur, my daughter’s lover, onto the zombies I clobber or shoot or incinerate. I bring a crowbar on my patrol one night. I imagine access to a sonar map of the Avenues in which I am the locus of radiating pings and my daughter’s boyfriend is an elusive red dot. Manholes, too, are marked.

I begin expecting the infected to pop out at me, and I scout for escape routes. I see a section of the fence around the graveyard that has been displaced, and I gauge whether or not it’s enough space for my character to fit through.

I love how the post topples in segments, in super slow motion. The way wrought iron gives way to chain link. The mysterious symbol on the third block from the bottom.

In ZombiU, I would scan this symbol with my gamepad and it would provide me with a clue to a clue to a clue that would lead me to Arthur, my daughter’s lover.

March 22nd

We are infected—piano has taught me that. Twenty years ago I taught my hands a Chopin mazurka, and these past two weeks my hands have taught it back to me. It’s so strange how much knowledge lives on in us unacknowledged, atavistic/instinctual or just part of our daily ballet. I reached a level in ZombiU called “Ron Freedman’s Flat,” which includes a room where you have to pick off zombies that have been lulled to the nepenthe of throbbing bass and black lights. Even though they’re not technically alive anymore, their bodies remember actions they performed during life and respond automatically to stimuli.

I put my wallet in the toaster today.

Trying to memorize the Chopin, my brain will alert me to a difficult series of upcoming measures. I’ll be fine now, fine now, but I’ll feel the approach of chord or ornamental figure that I know will trip me up. And it will trip me up, and I will go back to one of my bookmarked measures and start again. But that chord or figuration is not content to simply remain resistant and rotten; it will spread its clumsy amnesia backward to meet my oncoming fingers. I will greet the dementia a measure earlier than before, rewind again, get tripped up two measures before the first time. More and more of the piece will fall into darkness until I end up admitting forfeit and bringing the sheet music back out so the whole mazurka isn’t engulfed.

I worry that all memory works this way. For example, I’m confident in my general memory of our “therapeutic” family trip to Zion the year before the divorce, or Bree’s reluctance to move back in with me when she didn’t get accepted anywhere but the U. But then I try to recall something specific from those scenes—the words of a conversation, what we ate for dinner—and my inability to do so taints the whole year of life with such unreliability that I’m left wondering if it ever really happened.

March 23rd

This morning I awoke to find the city workers applying sealant to the section of 1st right in front of my house. Behind their truck they pulled a giant orange tank streaked with tar and dirt, and I wondered about the similarity in temperature and consistency of this sealant compared to the tar used in the defense of castles in the Middle Ages. Google: tar or pitch, along with stones, hot sand, molten lead, and boiling water were dropped on enemy soldiers from “Murder Holes,” holes in castle ceilings, barbicans, or passageways. Google: tar is more or less fluid, depending upon its origin and the temperature to which it is exposed. Pitch tends to be more solid.

My mind moved to treasure seekers combing the beach sand with metal detectors as I observed the workers trace their wands over the asphalt in cryptic glyphs. Wikipedia: “The simplest form of a metal detector consists of an oscillator producing an alternating current that passes through a coil producing an alternating magnetic field. If a piece of electrically conductive metal is close to the coil, eddy currents will be induced in the metal, and this produces a magnetic field of its own.” No, the discs at the end of the wands were more like the spongy proboscis of houseflies, trailing a line of black blood instead of lapping it up. Google: labella.

The workers chatted about an overly affectionate cat that had disrupted their workday, about the prospect of giving it a black stripe of sealant, about an episode of Pepé le Pew remembered from childhood. For half an hour they discussed where they’d eat lunch. One of them was in favor of Whole Foods, the other Wendy’s. After they’d moved on, I stepped outside to examine their work. The newly laid sealant was a blacker black than old sealant but glistened gold in the sun, veining the dull asphalt with light.

In places, the sealant pooled in shallow potholes like miniature versions of the tar pits that trapped dinosaurs and preserved their bones. Wikipedia: “Most tar pits are not deep enough to actually drown an animal. The cause of death is usually starvation, exhaustion from trying to escape, or exposure to the sun’s heat.” Wikipedia: “Over one million fossils have been found in tar pits around the globe.” Wikipedia: “‘The La Brea Tar Pits’ literally means the the tar tar pits.” I was bothered by places where the workers had not dispensed enough sealant to fully pool the concavity. It seemed like they’d missed an opportunity to clear a wound of dirt.

No, I realized, not clear the dirt. I wanted infection. Containment of today’s irritants, a burying again of the meager portion of planet that sees light and feels the wind. Perfect infection. It seemed unfortunate to me that tire tracks already dirtied the tar in places, an irrevocable and inevitable tarnishing given the tar’s consistency. Wiktionary: “tar” and “tarnish” do not share an etymology. Even if they did, tar can be tarnished—and the more dust that sticks to it, the more it’s pressed down by tires, the more that it’s weathered by sun and snow, the less likely you are to notice it. Unlike the usual tarnishing that stands out as a defect—like a stain on a shirt or a crack in a dish—tar is tarnished into invisibility.

HOT CRACK SEAL diamond-shaped signs warned drivers, and I had the urge to test the substance. I found it quite cool and pliable.

My fingerprint held its shape for longer than I cared to watch.

(Stepping back out an hour later, I was relieved the divot was gone.) As there were many more cracks in the asphalt than the workers could possibly have filigreed, I wondered what their system was for determining that this crack was fine for now while this other needed attention. Rich, what’s yours?

It’s true: at Whole Foods you can accidentally spend like fifteen dollars on a salad.

March 24th

The cemetery by my house was brought up as an option when Bree’s death forced Gail and me into conversation. She suggested it might be difficult for me to live in such close proximity to Bree’s grave. I thought it was a hilarious suggestion, but I didn’t laugh.

March 26th

It’s one month since Bree’s death, and I could tell at our session this morning that one month is Rich’s milestone for tiptoeing the concept of forgiveness into the conversation. A difficult homily to a man who walks the streets for hours every night looking for blood. I didn’t respond well at the session, but now I have a moment to consider what makes forgiveness so difficult in this situation. I’ve tried to imagine him (I’ve imagined him a him) generously, someone beaten down by society, someone sick and poor who met the wrong prophets at the wrong time. I imagine him ignorant of his actions’ consequences—or, knowing, bereft. A story of the Aves and the Ave-Nots. I imagine him as Arthur, a tenant I evicted from my Liberty Park rental a few years ago. I’ve had to evict tenants before when they’ve fallen behind on payments, promised they would pay me back if I could just give them more time—but Arthur was the only one who I believed and evicted anyway. It’s a stupid, impossible fantasy, just my attempt to imagine some kind of scenario in which I deserve this misfortune. (I never attempt to fit Bree into this equation of who deserved what.) Once I imagined Arthur’s face on the shadows I screened for, it was locked there and I couldn’t shake it. Recalling his last name, Stenger, I imaged him the timid tagger MOST, signing his name on the wreckage of my household as an elaborate work of revenge art.

When I imagine forgiveness, I imagine someone kneeling before the one he or she has wronged, a benevolent hand eventually placed on the shoulder or head of the wrongdoer. Rays of sunlight. But forgiveness is especially noxious in my situation because he might not even know he’s wronged me, wronged Bree. He might have experienced none of the setbacks in life that I’ve imagined. Forgiving someone who has not asked—does not even know they require forgiveness—someone who might right now be continuing to enact the potential need for forgiveness from any number of strangers… Perhaps the person and the guilt we’re forgiving is always a projection, but in this case what I’d be forgiving would not be an actual human, but something in myself. And, currently: no.

March 27th

This heart on a telephone pole in my neighborhood:

What’s the first thought this cheery decoration inspires? The violence of a screw through the heart’s heart. My mind these days.

March 28th

I haven’t sat down at the computer in my home office for a while, but today I was feeling particularly anxious about Kenneth’s ability to deal with my work responsibilities in addition to his own. Taped above my computer, I saw and remembered, is a printout of the fake email I wrote under a pseudonym that got me in so much trouble, the leaking of which—coinciding with Bree’s death—led to my mandatory leave.

Free speech has its limitations; the most frequently cited example is yelling drought in a desert. Shortage during a shortage. Double sacrifice, career and daughter of Senior Analyst, to mountain gods appeased. It’s barely stopped raining since the funeral.

March 30th

With nothing else to do, I drove two hours today and visited the Spiral Jetty for the first time in my life. Surrogate brain: “The sculpture becomes submerged whenever the level of the Great Salt Lake rises above an elevation of 4,195 feet (1,279 m). At the time of Spiral Jetty’s construction, the water level of the lake was unusually low due to drought. Within a few years, the water level returned to a normal level, submerging the jetty for the next three decades. In 2002, the area experienced another drought, lowering the water level in the lake and revealing the jetty for a second time. The jetty remained completely exposed for almost a year. During the spring of 2005, the lake level rose again due to a near-record-setting snowpack in the surrounding mountains, partially submerging the sculpture. In spring 2010, lake levels receded and the sculpture was again walkable and visible. Current conditions fluctuate.” That’s either from Wikipedia or the ether, but I searched current conditions fluctuate moments after copying, pasting, navigating back—and the phrase was cut from the entry, edited away by a stranger. Current conditions do not fluctuate, apparently. It’s our confident knowledge that’s suffering a constant erosion.

I walked the length of the Jetty to the center, my sneakers collaborating with its entropy. Back to my car, however, was a straight line.

A young couple Bree’s age pulled into the parking lot with a kayak on top of their car, apparently failing to anticipate how far the lake had receded from its usual shoreline. I call this washed-out photo “The End of a Relationship.”

It was very sunny.

A couple hundred yards south of the Jetty are the lithic remains of an oilrig from the 1950s.

Oil seeps from the lakebed where the petrified forest of old dock posts juts skyward.

Texture-wise it reminded me of a tree on 1st Avenue, the barky carapace of slow spillover where the trunk takes root at the corner of lifting sidewalk slabs.

The oil, you can play with it.

And, like tree bark, it eats irritants at glacial pace.

March 31st

Today I added a paragraph to my fake, all-too-real e-mail to SLC residents:

April 1st

Today I started learning a piano piece just because I like the name, Debussy’s prelude La cathédrale engloutie (The sunken cathedral). I’m starting to remember why I had to finally give up trying to relearn the piano years ago. I always told myself starting back in that my life would be enhanced if I could just play, say, that one Chopin mazurka I love so much. But then my usual human affinity with the number three would make me want to learn two more pieces, perhaps become a Chopin expert of sorts. No, I would learn one piece—or three pieces—from all the major movements in old music: baroque, classical, romantic, modern. Pretty soon, one hour of practice a day would become two, three, and I’d again recall that I seem unable to just dabble in piano.

Wikipedia: “This piece is based on an ancient Breton myth in which a cathedral, submerged underwater off the coast of the Island of Ys, rises up from the sea on clear mornings when the water is transparent. Sounds can be heard of priests chanting, bells chiming, and the organ playing, from across the sea.”

I’m also remembering that the more you try to channel passion or sadness or joy from your real life into your performance, the more you tend to botch it. Your mind must be like the driver on a highway whose exit is coming up pretty soon.

April 2nd

At night I’ve made it a habit of walking on the street rather than on the sidewalk, mainly because so many of my neighbors have motion sensor lamps with the wattage of a prison guard tower spotlight—and/or hyper dogs who don’t know they live in the Avenues. These streets are quiet at the hours I walk, but I’m always alert for cars, especially since I’ve been dressing in darker and darker clothing in anticipation of meeting Arthur. Tonight—I guess it’s last night technically—I heard the sound of a car approaching me from behind. I stepped aside, but something was different than usual. Then I realized: the car didn’t have its headlights on. Then it did—its red and blue strobes as well. Even as my heart quickened, I reasoned that it probably had nothing to do with me, and I waited for it to pass.

But a cop got out of the car and began to approach me. Backlit, her features were indiscernible to me even as I was blasted with light for her.

“Sir, may I speak with you for a moment?”

“Is there a problem, officer?” I delivered my line.

“Can I ask if you have any weapons on you?”

I told her that I had a crowbar, if that counted as a weapon, and I set it down on the pavement. Yes, that is my only weapon. This bag contains a camera. I handed her my camera bag. She unzipped it and gave it a fleeting inspection.

“What are you doing out here tonight?”

“I’m just out for a walk.”

“Why are you carrying a camera and a crowbar?”

I didn’t reply.

She continued, “There have been reports of a suspicious man walking around the neighborhood, filming. And we’ve had a problem with theft of sewer covers in Salt Lake City recently, including in this neighborhood. Would you know anything about this?”

Again, I was in possession of such exact answers to her questions that I struggled to articulate them. She seemed to interpret my silence as resistance.

“Do you live in this neighborhood?”

“Yes,” I said, “I live on 1st Avenue. The man with the camera is probably me, but I haven’t been shooting video, just taking stills for this project I’m working on.”

“Project?”

“The theft of manholes is why I’m out here. Like the neighborhood watch.”

“It seems that the neighborhood watch is worried about the neighborhood watch.”

The sign was disconcerting to me as a kid; I thought the watching-eyed black figure was the neighborhood watch, rather than a caricature of the type of man the watch wanted to scare off. (I’d imagined him a man.) I never liked the straight line from the tip of his hat to the small of his back. I never liked how the forbidding red bar obscures any tapering of his midsection, as if his gumshoe hat is the peak of a crooked mountain. His hat spins like a top when he’s excited; I’m not sure why, but it does. I still can’t figure out the slice in the side of his head. If it’s a leering grin, then the letch has an eye at his ear region or a mouth on his cheek. Is that the collar of its trench coat or the jut of a bottom jaw? I guess maybe he’s talking out of the side of his mouth? Psssst…

“Why do you have a crowbar with you?”

“Why hasn’t the city installed locking manhole covers?”

“I’d like you to come down to the station with me just so we can clear a few things up. Are the photographs you’ve taken still on this camera?”

I didn’t want to get taken down to the station or even sit in the back of her car while she sorted things out.

So I told her.

April 3rd, 2015

TAKE SHORTCUT

X

Venn overlap of tragedy and comedy. Our cities are pocked with holes—but as we drive through the rainy night, we trust that the covers will be in place. Rather, we don’t even think about it. Maybe tomorrow, but no hole will open in my life today or today or today.

April 5th

Rich asked me at my session this morning if I think I’m making any progress. I wanted to tell him that the question is stupid and canned. I’m not sure if progress would look like grieving less or grieving more.

But I realized today that I am making progress. Just one month ago I was asking road sealant to form the letters of the Latin alphabet. While I continue to be suspicious that all things visible and invisible are a form of writing, I’m beginning to understand that they speak to us each in their own distinct languages, and that any attempt at augury—inevitably biased and imperfect—requires transcription. Maybe this is what separates artists from the rest of us.

Desperate our clinging to this crust. Fragile our traction. How utterly dictated by coincidence is all life on this planet, even more so the circumstances that impossibly collided to make me this creature here and now rather than someone else some other time, some worm, or continued nothingness—all the possibilities of existence and non-existence in the infinite combinatory of life. So maybe I can stop holding court against one tragic coincidence, zoom out and count the heap of flukes that endow me with the love and sorrow and language to name them. Maybe I can start a new grief journal that grieves my lost daughter instead of myself.

Two dots in time and space wretchedly intersected. That is all.

And when we’re gone, if we’ve failed at our mission to eradicate life on planet Earth, how long before there are no traces we were ever here? Cosmic time, proportional to our brief tenure.

In my dream I must have gotten a job as a city utilities worker, because I’d taken the liberty of bringing home some equipment. The tar tank had a pull cord and started like an outboard engine. My first line of black tar was reserved for her laptop. I coated the keys, the screen, the speakers, the mouse, the hinge where it closes. I sealed the line between her mattress and headboard, headboard and wall, all along her pillow. You’d need a knife to open her closet and chest of drawers after I’d finished with them. Her alarm clock was no good anymore.

Internet: the Jewish tradition of covering mirrors during the ritual of Shiva is of uncertain origin, one theory being that—since humans are created in the image of God, and since a human’s demise represents a rupture between living human and living God—the image of the Creator itself shrinks with the death of its creatures.

I covered the mirror in Bree’s bedroom—then all the mirrors in the house. The task of containment felt incomplete, and I applied a line of sealant all around her doorframe, my dream-physics causing it to stay put and not drizzle down the face of the door. Following some alterations, my upright piano featured 36 black keys and 52 black keys. My cell phone and camera were encased where they sat. Let the windows be shut upon them.

Still dissatisfied that some therapist or third dot might disturb our hard-fought solitude, I applied a gag and blindfold—so that, should I ever make it back, I would never be able to betray the route to friends or enemies.