The day of his daughter’s arrival, Daniel cut back the Marilyn Monroes. He’d pruned them every January for the past ten years. The roses were a true victory—he’d been called a gambling man by a horticulturist who warned Daniel he wouldn’t be able to keep Marilyn Monroes alive. They were too finicky, they required a frost in the winter and the temperature didn’t drop low enough in Tampa. But Daniel knew he could keep any plant alive.

Daniel wasn’t sure why Hayley was coming home. Hayley’s email had said: “I want to say goodbye to the house.” Why? How was it possible to tell a house goodbye? If his wife, Olivia, had still been alive, she would’ve explained it.

The house was packed, and the movers would be there the following week. Daniel had already shipped most of Hayley’s belongings to Los Angeles. Daniel knew never to throw away anything Hayley owned. When she was a little girl, Daniel had made the mistake of throwing away a headless Barbie he found by the pool, and Hayley grieved the loss of the doll for weeks. Olivia had been livid. She’d called him heartless and ordered him to never touch his daughter’s possessions again. For Daniel, objects had little history or future. He couldn’t understand why Hayley and his wife had gotten so upset. But Daniel remembered Barbie when it came time to pack up Hayley’s things. He tossed everything from her room into boxes without examination. Just a few packages remained to be sent to her in California.

He finished tidying the roses. There was still enough time for a Gatorade and a shower before Hayley arrived. He’d just stepped into his bedroom when there was a loud knock at the door. He found his daughter on his steps. It was the first time she’d been home since his wife’s death a year back. She smiled up at him.

“Hello, Daddy,” she said, shyly.

Despite the fact he knew nothing about her—favorite color, movie, food—still, his chest grew warm at her smile. The same smile she’d had all her life. He was shocked by how much he wanted to pull her to him. He remembered the satiny feel of her skin when she was an infant, the way she’d kicked her feet when he said her name.

“I got on an earlier flight,” she said. “I tried to call you.”

Damn iPhone. Since his retirement, he forgot to even turn it on.

“It’s so weird here,” Hayley said, her voice an echo in the cavernous dining room. Olivia had wanted the drafty old house. Daniel couldn’t wait to sell it.

“Do you really want to move?” Hayley asked, trailing a finger across the top of the buffet, the only piece of furniture he was keeping because it had been his grandmother’s. When she looked at him again, the smile from the doorway had disappeared. There were dark circles under her eyes, creases on her forehead. How old would she be now? He did the math. Born the year he’d made partner. She’d be forty in June. There were small patches of grey at her temples, her hair the color of chestnuts now instead of purple.

“I don’t need the space now that it’s just me,” he said.

“It’s so weird without Mom,” she said. “Isn’t it weird?”

It had been. For a little while. No rattle of Olivia’s old Mercedes. No smell of lemon in the morning. Now it felt normal. And good. Of course, he couldn’t say he didn’t miss Hayley’s mother, that he realized at sixty-seven he’d never been in love, and probably never would be.

He said, “Yes. Very weird.”

“I’d like to lie down,” she said. “Long flight.”

He’d left her twin bed in her room, and he led her there.

“I’ll be up in a few hours,” she said.

—

He ate at the deli for most meals now and his cabinets and fridge were bare. While Hayley slept, Daniel went to the grocery store and stocked up on all the things Olivia kept around: Stouffer’s frozen lasagna, bananas, whole wheat bread, butter, coffee. He remembered Hayley eating a cereal called Lucky Charms, so he bought a couple of boxes, happy that he remembered one thing about his daughter.

At just after seven that evening, Daniel knocked on her door. He’d heated up a lasagna, and it was getting cold. Hayley didn’t answer and, when he poked his head in the room, she said she needed to keep sleeping, that she’d had a “rough few weeks.” Should he ask her if anything was wrong? Was sleeping a bad sign?

On one of her last days in the hospital, Olivia grabbed him by the wrist and pulled him to her. So close he could see the red veins intersecting the whites of her eyes. This was the closest they’d been in many years.

“Promise you’ll talk to Hayley. She’s in a bad way.”

Daniel hadn’t been able to tell she was in a bad way. In fact, he hadn’t seen her looking so good in years. No purple hair, no bitten fingernails. The way she looked, it was hard to believe she was mentally ill, though Daniel wrote a check for $2400 every month to pay for her therapy.

When had his daughter become bipolar? It made his jaw clench to remember the promise Hayley had possessed—acting lessons, school plays, her declarations that she wanted to be the next Nicole Kidman. And she’d been so pleasant—squealing with laughter when he chased her in the pool, making up dances, using the cabana as her stage.

Since Olivia’s death, Hayley had called once a month, always on a Sunday night. They talked about rain. The lack of it in Los Angeles, so much in Tampa. If Olivia were around, she’d ask Hayley questions: Are you taking your meds? Going to bed at a reasonable hour? Working? But she had the right to ask. Daniel didn’t ask questions. What would he do if Hayley gave him answers he didn’t understand? Olivia and Hayley had their own secret language. Olivia bought a ‘best friends’ necklace and gave Hayley the ‘best’ half for her tenth birthday. The one time Daniel wondered if Hayley should have friends her own age, Olivia’s eyes filled with tears.

“My daughter is here for me. Which is more than I can say for you. You’re a stranger to us.”

No, Daniel would let Hayley sleep. He would leave her alone.

—

Just after eleven the next morning, Daniel heard the click of her doorknob. He was at the sink, rinsing a bowl when she padded into the kitchen. Bare feet, wearing a faded blue T-shirt and a pair of jeans. Her hair stuck out in a million directions. She looked the way she had in high school, after a night dancing, her hair reeking of smoke, making him wonder why he was spending thirty thousand a year on private school when she partied with the public schoolers and brought home Cs.

They said “good morning,” and he gestured to the box of cereal on the table.

“Your favorite, right?”

She smiled. “I don’t eat sugar anymore.”

Hayley grabbed a bottle of water from the counter and picked up a banana from the bowl. He waited for her to say something else. She didn’t. She left the room and, a few minutes later, he looked into the backyard to find her sitting beside the drained pool, her legs pulled up against her chest. The half-eaten banana was by her side. Her face was turned away. Was she saying goodbye to the pool?

After a few minutes, Hayley stood and went over to the steps. She walked into the empty concrete basin. She walked to the center and then stared up at the sky. Daniel craned his neck and looked up, too. Seagulls, a whole flock of them, flew in a V shape across the sky. A memory: feeding bread to the seagulls with Hayley when Hayley was a child. Hayley loved to chase the birds, and he had laughed and encouraged her to run faster. There had been good times. A few of them. Daniel considered walking out to the pool, bringing the loaf of bread with him. But Hayley might want to be alone. She might’ve come home for the peace she never got when his wife was around.

When Hayley came home for Christmas, Olivia made sure they had a packed calendar: ringing the bell for the Salvation Army outside of Publix, a carol sing-a-long at the nursing home.

“The worst thing she can have is quiet,” Olivia always explained. “I must keep her busy so she doesn’t focus on her sadness.”

But what if this wasn’t true? What if peace was exactly what Hayley needed? Daniel had been to Los Angeles once, and the traffic and smog had been as much of a shock as the coffee shop where Hayley worked, a den of tattooed and pierced people who huddled over laptops all day. Didn’t people in LA work? Why weren’t they at offices?

A few minutes later Hayley came in the house. He walked to her room. She sat on her twin bed, her back to him. He thought he saw her shoulders shaking.

“The new people are going to fill the pool in,” he said. “I had to drain it.”

“You never used it anyway,” Hayley said. “Mom and I were the only ones who ever went in.”

The cold tone of her voice was a shock. Better to give her space. Daniel shut the door.

Hayley didn’t come out again until dinner. He heated up another lasagna, and they ate it on paper plates. The only sound was when he blew on the noodles. After they finished, he asked her if she’d like to go for banana splits, a peace offering since she’d sounded angry about the pool.

“No sugar,” she said, eyes glued to her plate. “Remember?”

She picked up her iPhone and began typing, probably a text about what an idiot he was. Daniel cleared the table.

—

The next day Hayley sat out by the pool again. For hours. When it rained, she sat under the awning. He thought he saw her crying, but he couldn’t be sure. He wished his roses were still blooming. He could’ve shown her each one. She’d liked the garden a long time ago. She’d helped him add just enough aluminum sulfate to the soil to turn the hydrangeas blue. Seagulls, ice cream, flowers. The memories served as proof there’d been times when he knew things about Hayley. If only he’d tried harder, they could’ve been closer. But when Olivia was alive, it was like she and Hayley were the only people in the house. His presence was more like a shadow, lurking, ready to be dismissed, a stranger indeed.

Daniel took a nap and woke just before dinnertime. Hayley wasn’t in the backyard and she wasn’t in the kitchen. The door to her room was closed. He heard talking. He walked past, not wanting to disturb her, not wanting to eavesdrop. But what if something was really wrong with his daughter? What if her trip home was a cry for help? Was he being too dramatic?

He tiptoed back down the hall and pressed his ear against Hayley’s door. Murmuring.

He couldn’t make out words. But then: “I burned all those bridges,” Hayley said, shrill enough that he could make out each word. “I have nothing to go back to in California.” A cry. A moan.

Daniel gritted his teeth. He retreated into the darkness of the hallway, to his bedroom. He didn’t sleep for hours. He kept hearing his daughter’s words. “I have nothing to go back to in California,” she’d said. What did that mean? Had someone broken her heart? Had she lost her job? Who was on the other end of the call? He wished he could contact that person and get the story. Asking Hayley about it felt impossible.

He pictured her apartment in Los Angeles, the one time he’d been. The cactus in the windowsill. She explained it bloomed at Christmas. He’d taken her to the local nursery and bought her more cacti. “They don’t need much attention,” she’d explained. “I can always keep them alive.”

He’d thought that was weird then, another way they were different, another way he didn’t understand his daughter. Daniel loved that his roses needed him. They depended on him for water and food. They flourished under his care. Hayley and Olivia hadn’t flourished under his care. Olivia told him no amount of money could ever make up for the fact that he never laughed at her jokes, that he didn’t appreciate her thoughtfulness.

One Valentine’s Day she bought candy apples etched with hearts for him to bring to the office. Whoever heard of a grown man, the head of a law firm, bringing in candy apples for his employees, the same employees who were supposed to be terrified of asking him for time off at Christmas? He said he wouldn’t bring them in, and, one by one, over the next few weeks, Olivia ate the apples, crunching loudly, glaring at him.

Olivia wasn’t thoughtful. She wasn’t kind. But maybe she was right about their daughter. Maybe Hayley was in a bad way. But what could he do?

—

Sometimes, when clients were in town from far away, he took them to Palm Valley Fish Camp because the restaurant was famous for its fried shrimp. Would Hayley like fried shrimp?

He knocked on her door the next morning and, when she opened it, he suggested the dinner nervously. He expected by her swollen eyes that she would say no. But to his surprise, her face lit up the way it had when she saw him the night she arrived.

They decided on seven, and twenty minutes before she walked down the hallway wearing a cherry red dress with a puffy skirt and shiny black high heels. An outfit too fancy for Palm Valley Fish Camp, which was out by the marsh, and a place where the staff looked the other way if you smoked on the porch. Daniel always bought cigars for clients.

“Mom bought this for me to wear to prom, but I didn’t go. I chickened out. I never got a chance to wear it. Do I look okay?”

The dress was too big—the sleeves drooped off her shoulders and the bodice gaped at the bust and waist. How was she so much smaller at forty than at fifteen? She wore too much red lipstick—there were smudges below her mouth. The white powder on her face made her look like a ghost, reminding him of Olivia in her coffin. He wanted to tell Hayley to change. He didn’t like being embarrassed. But he forced himself to smile. “You look nice,” he said. Then he opened the door, and she followed him outside.

—

Daniel had forgotten it was Friday, and they had to wait a long time for a parking spot. Hayley hummed beside him, tapping her fingertips on her knees. He clutched the steering wheel, wondering if he’d made a mistake by inviting his daughter to dinner. But Olivia’s words reverberated in his head. “Promise me you’ll talk to Hayley. She’s in a bad way.”

—

They had to put their name on a long list and there was nowhere to sit to wait. They stood by the porch, where the air smelled like smoke and beer. Mosquitoes hummed in Daniel’s ears and he smacked the bugs away. Hayley kept curling a lock of hair around her finger, letting it go, and doing it again, a habit from her teen years. Daniel could feel the stares of the other patrons when they noticed Hayley’s dress. He kept a smile on his face, praying no one would comment. It wasn’t likely he would see anyone he worked with at the restaurant. They frequented the places in town or the club, where hush puppies weren’t an option.

Finally, their name was called, and they struggled through the knot of people to the hostess stand.

A girl in jean shorts smacking gum led them to a table in the middle of the restaurant, beside a table of guys wearing baseball caps. Daniel felt their eyes on them, and he glared at the biggest one, a burly guy in a Gators sweatshirt. Hayley said she needed to use the bathroom as soon as the hostess set their menus on the table.

It was so loud that conversation wouldn’t be possible. Daniel was grateful for this because his daughter was acting so strangely and he didn’t know how to find out why. Seeing Hayley twirl her hair brought back bad memories of sitting across from her at the dinner table. A typical night: Olivia chattered about the candlesticks she’d just bought from QVC while their daughter twirled her hair and didn’t say a word.

Then there were all the absences in high school. Olivia made excuses. “She’s not like the other girls. She’s sensitive. I can’t make her go when she’s sad.” But why was Hayley sad? He’d never understood. She had everything: diamond stud earrings that matched Olivia’s, an Audi TT when she turned sixteen. But more than material things. Daniel had given his daughter promise. Possibilities. The perfect start to a perfect life. Much more than he ever had, growing up in rural Alabama with a single mother who could barely scrape together enough money to put tuna fish on the table.

Hayley could’ve gone to any college in the country if she’d just kept her grades up. But she hadn’t. The only college that accepted her was a tiny one in North Carolina, which she returned from on holidays eager to read them poems she’d written. He remembered one in particular—she said her heart had been attacked by tigers and there were teeth marks in the aorta. The poem was titled: “Mother.”

Olivia had started crying when Hayley finished. Daniel’s first impulse was to comfort his wife, but she’d jumped to her feet, clapping her hands. She called Hayley a genius, framed the poem and hung it on the bathroom wall. It looked at him while he brushed his teeth. “She hunts me nightly. She never wants to let me go.” Hayley’s poem seemed to be a negative reflection on his wife. So why did Olivia like it so much? Daniel couldn’t fault his daughter for her feelings—after all he would’ve liked to write mean poems about his wife, too. Daniel didn’t understand poems. And he knew then he would never understand his wife and daughter. He’d always be on the outside, walking by the den where they huddled on the sofa, sharing a bowl of caramel popcorn.

Hayley returned to the table, her lips redder, her face paler. She sat down and the waitress appeared, barely glancing at them, scrawling their orders down on a pad. Fried shrimp for both of them. Hayley wanted a glass of white wine. He wanted a scotch and soda.

The drinks didn’t take long and thankfully, the food didn’t, either. While they ate, Hayley twirled her hair and stared past him or studied her phone. He played with the dial on his Rolex, watching the time creep past.

When the waitress passed by to ask if they wanted key lime pie, Daniel handed her his American Express.

He met his daughter’s eyes across the table, and she smiled. She seemed to be on the verge of saying something, but then her smile disappeared and she stared at the half-eaten coleslaw on her plate.

“Still making cappuccinos?” he asked, searching for something to say. And then to his horror, Hayley began to cry. So, she had lost her job again. One second she was smiling and now her shoulders shook, quiet sobs wracking her body. Daniel remembered Olivia’s words again: “She’s in a bad way.” What should he do? He thought about client dinners, but no client had ever cried before.

Eyes on them. The men at the table nearby. Theirs was not the kind of community where you had a breakdown over coleslaw. “The land of the raised pinky” is what he’d told his wife once and she said: “We’re lucky to live somewhere so beautiful. Don’t complain.” Daniel had to get them out of the restaurant. The waitress returned—thank God—he signed the bill and grabbed his daughter’s arm.

He was grateful to be outside again. It meant the night was almost over. He breathed in the chilly air and thought of his roses. The cold would do them good. He hoped the person who bought his house would care for them the way he had. He should probably pass along his tricks: eggshells and tea bags in the soil, olive oil rubbed onto the leaves.

They were almost to the car when Hayley’s name was called. Oh no. Who could it be? Had someone seen her crying? The caller was a pregnant blonde woman in a floral dress.

“I thought that was you,” she said to Hayley, whose eyes were wet and frightened. “This your father?”

She stuck out her hand, and Daniel shook it and introduced himself.

“Elizabeth,” the woman said. “Hayley and I went to high school together.”

She told them she practiced obstetrics at Baptist Medical, that she was on her way to the hospital because one of her mothers was going into delivery early, much to her husband’s dismay since they’d been celebrating his birthday.

“My drunk husband can’t drive me to the hospital, and with my belly I can’t fit behind the steering wheel—could you give me a ride to the hospital? It’s less than a mile away,” Elizabeth asked.

This was the last thing Daniel wanted to do. He needed to get Hayley home, rescue them from the awkwardness of the night. Who was this Elizabeth? Couldn’t she call a cab? He could feel his daughter’s eyes on him.

“Okay,” he said.

Hayley went back to twirling her hair. She walked behind them. Elizabeth got into the front seat. When he pulled out of the lot, Elizabeth looked over her shoulder and smiled at Hayley.

“What are you doing these days?”

Daniel glanced in the rearview mirror. Was Hayley crying again? He didn’t want her to answer. She was a middle-aged woman who’d been hospitalized for bipolar disorder following a suicide attempt. This Elizabeth—she was the kind of woman Daniel had imagined Hayley would turn out to be. A doctor, pregnant, happily married. Assertive enough to ask an old schoolmate for a ride.

“I’m so proud of my daughter,” Daniel said, the lie falling out of his mouth so fast he couldn’t keep up. “She’s a brilliant writer. A poet. She lives in Los Angeles now, and I don’t see her enough.”

How had he come up with this so quickly? Five minutes ago, he’d been unable to think of a single word to say to his daughter, and now he was expertly lying to a total stranger. Maybe it was all those years convincing juries. He didn’t know but he felt proud of himself for jumping to Hayley’s rescue. He’d saved them both from embarrassment.

Elizabeth snapped her fingers. “I remember,” she said slowly. “We were essay partners in American Literature. Your papers were always the best.”

Hayley stopped chewing her cheek. “Really?” she asked.

“Oh yeah,” Elizabeth said. “I’m not surprised you’re a writer now.”

“I wrote a book,” Hayley said proudly. She opened up her purse and pulled out a worn copy. She passed it to Elizabeth. Daniel had never read his daughter’s book. He’d been too freaked out by the title, which had been the name of a song he wrote in college for a class. The only time he’d ever done something creative. He had no idea how Hayley got her hands on the song—he’d assumed it had ended up in the trash, like all of his college papers.

“Broken Nightingale,” Elizabeth said, staring down at the cover. “That sounds good.”

“Thank you,” Hayley said.

Elizabeth handed the book back and gave Hayley her business card. She suggested they have lunch the next time Hayley was in town.

“This is my last trip here,” she said. “My father’s moving to Jacksonville.”

“Shame,” Elizabeth said and then: “You look great.”

Hayley’s eyes grew wide. Daniel turned into the hospital parking lot and drove to the entrance. Elizabeth thanked him for the ride, and they all said goodbye. Daniel was certain now that the sadness inside of him was written all over his face, and he clenched his jaw as hard as he could. When Elizabeth got out, Hayley didn’t take her place in the front seat. They were quiet on the ride home.

When he pulled into the driveway, Hayley said, “I’ll be out of your hair in the morning. I booked an early flight.”

She was leaving? But she said she had nothing to go back to? She’d bawled at dinner. For the first time Daniel missed Olivia. She’d do something, even if it was the wrong thing.

They went into the house. Hayley went to her room. Daniel stood in the kitchen, staring out at the dark backyard.

—

Daniel got out of bed just as the light in his room turned pink. He went to Hayley’s room. He wanted to look at his daughter one more time before she left. She slept on her side, the covers down by her ankles. She’d slept like that as a little girl. Now her hair was short, but she looked just as peaceful. He wished she could know that peace, that her brain wasn’t so mixed up, that she didn’t get sad enough to want to die. Maybe her brain would’ve been different if he’d been a different father. If Olivia hadn’t been her best friend.

Hayley stirred. She opened her eyes.

“Daddy,” she said hoarsely.

Daniel’s heart pounded. He might never see his daughter again. She’d have no reason to come home now that there was no home to return to. She wouldn’t travel all the way back to Florida just to see him. The yard was beautiful in the morning. Maybe she’d like to see it one last time.

“Come outside,” he said.

She rubbed her eyes and sat up. She followed him, in bare feet, in her old T shirt and boxers, to the backyard. Now the sun was higher. Dew sparkled on the grass, made the tips of the blades look like diamonds.

Hayley turned to him, tears in her eyes. Should he hug her? Maybe she didn’t want to be touched. He tried to choose a word, any word, but his mind had gone blank like it always did with his daughter.

“I’ll have a balcony at the condo,” he said. His voice sounded strange to him, far away. “Would you help me pick out plants for it? A cactus maybe?” He wasn’t sure what he was saying, only that he was heading somewhere when a few moments ago he’d been at a dead end. How could he speak to packed courtrooms but not his daughter?

Her brow furrowed and she seemed on the verge of saying something. But then she stopped. This was a terrible idea. He should let her go. All of his earlier efforts had been futile. Why did he think he could help her now?

Tears coursed down her cheeks, shiny wet ribbons. This time the sight of her crying did a strange thing to him. A lump formed in his throat. He hadn’t cried in years, not even at Olivia’s funeral. He swallowed hard. Hayley moved toward him. She buried her face in his chest. His body tensed—it had been such a long time since he’d been touched—but then he smelled her hair. The same long ago, little-girl scent. Like roses, like baby powder, sweeter even. Daniel closed his eyes. He remembered: chasing her in the pool, tickling her stomach, making her scream with laughter. He’d never felt happier than on those days. Summer was coming. A few months away. This summer he would make her sadness go away. It might take some time, but he’d do it. He’d kept the Marilyn Monroes alive. He could do anything. At least, he could keep trying.

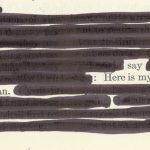

![Body of The [strikeout text] Fairy Tale.](https://cah.ucf.edu/floridareview/wp-content/uploads/sites/34/2019/10/Sirmans-image-1024x713.jpg)