Jonathan Fink

My youngest daughter does not know

that each tree ring marks a year of growth

when she selects a piece of scrap wood

from the sawdust and shavings

that have covered our back patio

and carries the board inside to color

the rings revealed by the saw blade,

my daughter filling the arching semicircles

until a rainbow appears as her sisters

lay other scraps across the floor to make

a path on which to leap from board to board

to furniture and back again in a game,

I imagine, every child in history has played,

the game requiring only the belief

that the ground is not as solid as it seems,

that a misstep or tip of balance will lead

to peril, whether lava or river or canyon below,

even though, while laughing, they jump again,

shrugging off each demise, protesting

only when I collect the boards

and insist that the world be ordered

over their appeals to fairness,

the mantra of childhood, to which

I and every parent I know responds,

Who says the world is fair? mostly resisting,

though sometimes not, to itemize,

while wielding a clothes-less Barbie

or broken toy like a judge’s gavel,

every slight from work and love

and politics both foreign and domestic

as the neighbor’s dog howls at the burgeoning

moon and the kids give each other that look

meaning, What’s got into dad—all we meant

was we were having fun? which is when

I see myself reflected in the glass

of the patio sliding doors and realize

how large I must seem to them,

large, though clearly not authoritative,

as the youngest starts spacing

the boards again behind my back,

and I lift one and point to the rings

in the grain, and say, see, this too

was once alive, how, though rooted,

it turned it leaves to the warmth of the sun

and drew water from the earth, its limbs

not unlike yours when you lift the hems

of your skirts to hop through puddles,

or wave to me from the treehouse

we are building together, a project begun

before the passing of their grandmother

though intersecting now with her loss

as grief permeates all things, and they ask

the questions one would expect

(if she looks down on them from above

just as they, from the tree, look down on me)

and the questions one doesn’t expect

about how the tree feels holding

the remains of another tree in its limbs,

transformed, though it is, to a house,

and I tell them trees aren’t capable

of abstract thought or have feelings

like we do, though what do I know,

thinking of Michelangelo’s Pieta,

and Mary, though stone, holding

her deceased son, and how the body

is itself a house of memory and love

and loss, as my wife and I explained

to our daughters, that the sadness they feel

is sadness, yes, but also love transformed,

that grief is love for the one who was lost,

just as my wife expressed on the day

before her mother died, after a month

of hospice at her mother’s home and the gift,

my wife said, to be there with her,

to measure and administer the morphine

when the great pain came, when any touch,

even a blanket, became unbearable,

to honor the effort at the end for her to stand,

holding to the walker, and request what would be

her final bath, and my wife, afterwards,

drawing a comb through the fineness of her hair,

never more beautiful, my wife saying

that night, and again the next day

even after the workers had come so quickly

to take her, to gather and remove

any remaining meds, count every pill

as her final breath still hung in the air,

and our daughters cried unceasingly

so that when, that night, we drove away,

the trees that lined the road seemed to bow

to the car, to lift their limbs in the breeze,

the undersides of their leaves lighter

than the backs, like the palms of hands,

which, I believed, if they could,

they would place on our car, on the shoulders

of my wife, or interweave their limbs

as a canopy above us, their petals

below, and the road would no longer

be a road but a tunnel, to where it ascended

I did not know, only that we were

like breath released at last from the throat,

becoming the words we were unable to say.

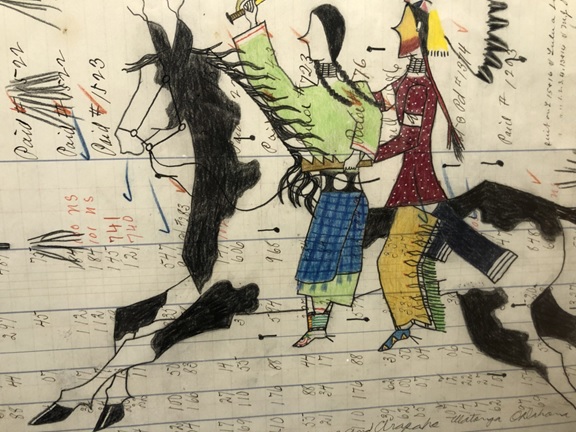

James Black

James Black Shann Ray

Shann Ray