Naomi Gordon-Loebl

1: Loma Prieta

In 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake split apart northern California. Sixty-three people died. Thousands more were injured. In Oakland, a stretch of the multi-level Cypress Freeway collapsed, killing some forty-two drivers and passengers who were unfortunate enough to be traveling at the wrong time, their bodies crushed between layers of concrete.

Soon after the earthquake, my uncle David called my mom. He told her that he felt a strange satisfaction in those days, walking around the city, among the wreckage, among the terror and the daze that had settled like an uncomfortable blanket over the Bay Area. Everyone else, he said, was finally experiencing what he felt every day.

2: Postcard

In June 1987, my mother was visiting her brother David in San Francisco, seven months pregnant with my sister and me. A postcard still survives from that trip, sent to my grandparents at their summer cottage in Maine. “We had a nice day—brunching & then walking in the Berkeley Botanical Gardens,” my mom writes. “Now we’re relaxing & making quiche for tomorrow’s pool party. What a social calendar!”

I imagine my mother, never exactly a partier, accompanying her brother to his many engagements. I love David’s handwriting, which I’ve come to recognize from years of examining his diaries and letters. It’s a gorgeous, confident script with a dashed-off feel. His addition to the postcard is briefer. “Am having a good time with J-J,” he writes. “Love + kisses.”

What the postcard doesn’t say is that during my mother’s visit, David’s doctor called with the results of his recent bloodwork. He was HIV-positive. My mother tells the story with the narrative distance afforded by thirty years. She cried on the plane in both directions, she always tells me: on the way there because she almost missed her flight and had to sprint, seven months pregnant with twins, through the airport to the gate. On the way back, well—she’s never had to explain that part.

3: Paper airplanes

My uncle David was my mother’s only brother. He was blond and handsome, and like me, the kind of gay person who could never pass for straight. When I was a child and he was in his thirties, he lived in San Francisco, in a series of apartments that I visited but can’t remember, except for the last one: a one-bedroom on 17th Street in the Mission, with a bay window into which he had tucked his kitchen table. We sat at that table, my twin sister and me, as five-year-olds, making hundreds of neon green and pink paper airplanes. David had died that spring. The paper airplanes were to pass out at his memorial; he had taught us how to make them on an earlier visit to New York. It is the only memory I have of him, except that I’m not sure whether I actually remember it at all, or whether the image—him in our little bedroom on the top floor of a brownstone in Brooklyn, standing next to my sister’s bed and tossing a paper airplane in front of the window with delight—is an after-market addition to my brain, an imagined scene that syncs conveniently with the story I’ve been told about that day. There is no way I will ever know. I sometimes think I can hear his laugh: a rich, high-pitched sound that dances just beyond the edges of my memory. Ironically, I feel more sure of that one; I am positive, somehow, that it’s accurate. My grandmother says she thinks she has his answering machine tape buried somewhere in storage. I’m desperate to hear it.

4: Mary

David and my mother grew up in Washington Heights. Their parents were refugees who had survived Nazi Germany and Austria against all odds. They were immigrants, grateful for their adopted country and eager to build stable lives after years of trauma and upheaval. They gave their children good American names: David and Judy.

Like me, David was gender non-conforming from the time he was a toddler. I tried to stand to pee, wanted to be called Jason. David wrapped scarves around his head as a stand-in for long hair and took the name Mary. My grandparents worried he might turn out to be gay. They feared they had done something wrong as parents; they believed, as my grandmother tells me now, that they owed it to their son to care for him in the best way they knew how. They sent David to a psychiatrist, who he saw until he was eighteen years old. When David was accepted to college at Brandeis, the psychiatrist warned against the move. David was at a critical point in his treatment, the psychiatrist said. If he went away from home for college, his progress toward life as a straight man could be lost.

My grandmother fired the psychiatrist. Enough was enough. She sent David to Boston.

5: Butch, femme

One of David’s best friends was a lesbian named Andrea. She lived in San Francisco, and she was a frequent visitor during his stay in the hospital in the spring of 1993. On one such visit, David showed Andrea a recent photo of my twin sister Ana and me. We were dressed, as we were in every photo from those days, like a pair of life-sized Ken and Barbie dolls: me in baggy jeans and a baseball cap, Ana in all-pink everything.

“Look,” David said to Andrea, pointing to the picture. “Butch and femme.”

I did not hear this story until many years after I came out. When I did, my world shifted. It occurred to me that David was almost certainly the first person to name my queerness. But more than that, the story ruptured a narrative that I had carried for a long time: that David and I had never overlapped as queer people in the world; that perhaps the only person in my family with whom I shared this tiny, precious detail of my existence had died unaware. This narrative caused me no small amount of regret, and to some extent, it is still true: David and I were ships in the night. But his ship had seen my floodlight scanning the waters. And his light had flashed welcomingly back.

6: PCP

David was on vacation in Argentina in February of 1993 when he came down with a bad cough. He flew back early from his trip, and soon entered the hospital with a diagnosis: pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, or PCP.

PCP is a rare lung infection that affects only those with weakened immune systems. Before the development of antiretrovirals, it was the most common opportunistic infection contracted by people with AIDS. David’s case was dire. His doctors had prescribed him a prophylactic regimen of antibiotics—an attempt to prevent what eventually came to pass—and he had maintained it despite a severe allergic reaction to the medication. Thus, the strain of PCP that he eventually contracted was drug-resistant. There were few options.

I was raised with the understanding that David was, in a way, lucky. He lived for years after he became HIV-positive. He danced, traveled, worked, and acted in plays—though he did not have another serious partner after his diagnosis. He never suffered from the myriad plagues that famously befell so many people with AIDS in the worst years of the epidemic: the blindness, the dementia, the public markings of Kaposi’s Sarcoma. He was healthy when he left for his vacation in Argentina that winter. Then, six weeks later, he was gone.

My mother has told me the story only once. She was visiting him in his hospital room when he began to cough uncontrollably. He coded. Nurses and doctors rushed in and threw my mom out. He survived the episode—an event technically known as acute respiratory failure—but he would never breathe on his own again. He spent the remaining weeks of his life in a medically induced coma, hooked up to a ventilator. On May 24, 1993, weeks after he entered the hospital, my family made the decision to remove life support. He was thirty-seven years old.

7: What is an uncle for?

An earlier version of me believed that David would have known everything. The kids who called me “lezzie” in middle school, the girl who broke my heart when I was fourteen, the woman who did it again when I was in my early twenties—I used to fantasize that my fairy-godmother-uncle, having suffered so many of the same wounds, survived so many of the same storms, would have solved it all.

It’s a nice fantasy—and David would be far from the first person who, having died, is made to carry in absentia all of the projections of the people he left behind—but a fantasy it is. I no longer entertain the idea that he would have had the perfect words to shepherd me through every difficult passage. He was a human, fallible as me, and I am reminded of that as every year I draw closer to the age that he was when he died. I am thirty-six now and still messy, still figuring out how to return emails in a timely manner, how to tell a friend I am mad at them before my anger bubbles out in the wrong way. What kind of magical thinking would I have to employ to believe that someone like me could save anyone?

What is an uncle for? A younger me might have said that an uncle’s purpose is to impart sage advice—to light the way, to offer what he’s learned from his experience traveling the same uncertain terrain you find yourself stumbling along. I’m less illusioned now. An uncle might be there to offer wisdom, the very rare kind that transforms the way you look at the world. Or he might be there to wax on with what he thinks is brilliant guidance, but which is barely relevant to your life. He might be there to draw comparisons that feel inaccurate, to tell you exactly the wrong thing, or even just to shrug and say, in a way that leaves you feeling dissatisfied and alone, that he doesn’t know. David might have been any of these uncles—or, most likely, some combination of them.

These days, rather than speculating about the lessons he might have shared with me, I find myself thinking about my uncle’s pain. Perhaps this shift toward empathy is natural. Soon I will be older than David ever was. I broke up with a girlfriend last year. It’s been a slow-moving rupture, the kind that aches for longer than you think it should. I don’t know how David coped when his last relationship ended; how much he cried, how many letters he wrote and didn’t send, how long before he felt better. Most of it I’ll probably never find out.

8: Lost uncles

For a long time, I worried that if David had survived, we might not have gotten along. What if he had driven me crazy? What if we had argued about gay assimilation every time I visited him in San Francisco? He might have left comments on my Instagram posts that made me cringe. Maybe I would’ve come home from every visit full of frustration.

“My uncle David,” I might have sighed to a friend over beers, back in Brooklyn. “We are just so different.”

Even so: I can’t shake the feeling that we would have learned something from each other too. Narratives of the early years of the AIDS epidemic often mourn the tremendous loss of talent: the dancers, composers, painters, actors, curators, and writers whose contributions were far from finished, their oeuvres forever incomplete. I wonder about all of the lost uncles, every queer friend of mine who, when they have heard about David, has leaned across the table and told me their story. What if every queer person my age had grown up with their Uncle David? What would we have learned from them? What would they have learned from us?

And with that continuity, so seismically disrupted—what would we have built?

9: Memorial

Last year, as a Christmas present, my younger brother Sean digitized our family’s home videos. Among the contents of the old cardboard box he sent off, reinforced with extra layers of packing tape, was a VHS tape which was familiar to me from the nearly three decades it spent sitting on a shelf in my parents’ living room, but which I had never watched. The label on its spine, written with Sharpie in my father’s capital letters, read: DAVID’S MEMORIAL.

Sean sent me a link in January. Even in its new digital form, the video has all the hallmarks of old home movies: fuzzy, unfocused images; distorted sound; dated outfits. It also has, as is often the case with pre-smartphone home movies, some attempt at narrative structure. The unknown person behind the camera takes pains to document the scenery of the memorial: a large room filled with arched windows, metal folding chairs, and bunches of rainbow balloons. Side tables are piled with food: mountains of bagels, platters of lox and sliced red onions, a carrot cake decorated with dozens of little carrots repeating across its rectangular surface, each of them finished with a tiny, iced green top. The videographer pans slowly across these tables, and the photo albums laid across them too, zooming in on some pictures that are so familiar to me that I could describe from memory the flowers that appear in the background, and others that I do not think I have ever seen before.

The program is not overly long, and in a way, it is unremarkable. A memorial service for a thirty-seven-year-old man is by definition unnatural: in the late twentieth century, thirty-something-year-olds with full heads of hair and lungs that could power them up Italian mountains on long-distance bike tours were not supposed to die. But as I watched the camera scan the room at David’s memorial, revealing dozens of good-looking young men in ties and jackets, I couldn’t help but think about how absolutely normalized this event was in San Francisco in 1993—how many parties with carrot cake and rainbow balloons these men would have attended by this point, how many guest books they would have signed, how many times they would have shrugged on those well-fitting suit jackets. Perhaps that’s why they smile as they greet each other; why they know how to dance when the music begins, an activity that strikes me as totally surreal for a memorial, even though I understand its rationale: this is a celebration of David’s life, and David loved to dance. As Robert, David’s best friend, says in his opening remarks: “This, I’d say, is certainly David’s largest party ever, and you know how he loved a party…although I think he’d probably be at the beach on a day like this.”

I appear in the video almost from the very beginning: a short-haired five-year-old wearing colorful shorts and a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles T-shirt. My immediate family is seated in the front row, and for some reason, I have chosen a seat by myself, across the aisle. I sit on the metal folding chair; my legs, too short to reach the ground, dangle in the air. The videographer, as though anticipating my specific interest in this video almost thirty years later, zooms in until only my face is framed in the shot. I do not look sad—which makes sense. What does a child who sees her uncle twice annually understand about death, about his forever-disappearance from a world she has only known for five years? I do, however, look alert. And in my hand, I hold the handle of a large white paper shopping bag. It spans the entire length of my bare shins. In a half hour, after the eulogies end, my mother will take the microphone to explain that my sister and I will be giving out paper airplanes in memory of our Uncle David. We walk past and through the hordes of tall adults, who at this point stand and stretch, preparing themselves for food, for dancing, or to say hello to the person they have not seen in a year. Our high voices punctuate the sounds of the crowd. “Did you get one?” we say. People seem to be humoring us, calling our names in request, and the camera follows me as I turn in every direction, reaching into the bag, handing out the airplanes two at a time, a sense of purpose and pleasure on my face. A red AIDS ribbon—one of the first symbols I can ever remember recognizing as a child—is pinned to my chest. In the next shot, David’s friend Frank stands and buttons his jacket, smiling. In the background, our airplanes fly through the air, their flights brief and sharp. People are throwing them.

In her eulogy, read aloud by a friend—another mother who lost her son to AIDS—my grandmother says David believed that people had “an essence from birth to death.” Of course my uncle knew who I was, I think, watching this younger but not-so-different version of myself stride around the room, the white paper bag hanging from my little fist. In the video’s last frames, the mourners dance to an upbeat, unidentifiable nineties tune while in the background, a home movie of David as a toddler, dressed in white and dancing with my mother, plays on a television screen.

10: Bedtime stories

My uncle David kept diaries. Slim, flexible notebooks with faded clothbound covers: one striped blue and white and dotted with tiny red roses, another covered in an abstract floral pattern in tan and green. My grandmother kept these notebooks after he died, and they lived on the towering mid-century bookcases in the foyer of my grandparents’ apartment, next to the photo albums filled with black-and-white pictures of David as a boy. It didn’t occur to me until I asked my mother about it that this might have been an invasion of David’s privacy, that maybe David would have been horrified to know that his mother had held onto his diaries like they were souvenirs from his bar mitzvah. My mom had made her peace with this fact—David was gone, she said, not here to feel violated or embarrassed, and how could she begrudge my grandmother any physical trace of her son that remained in the world—but she had never read them, and she would not.

Though I believed my mother’s ethical assessment to be the correct one, my desperation to know David outweighed my ability to self-regulate. From the time I was a teenager, I spent hours poring over the diaries in my grandparents’ apartment. I was enthralled by the person whose unfiltered voice spun across the pages in faded ink. Who was this man? The one who loved to eat and to travel, who detailed every dish he ate on vacation with impressive diligence, noting those that were “just okay” and those that were “delish,” whose ability to find dance floors and meet strangers wherever he went I found myself admiring, decades later. David spread out before me, opinionated, annoyed, delighted, alive. At the same time, as I suspect anyone who has tried to meet a person through their private writings can attest, in some ways he remained as opaque as ever. The notebooks were in my hands, but they might as well have been behind museum glass, flat objects that would never reveal more than the text on their surfaces, no matter how much I squinted. They were like pre-recorded bedtime stories, played long after the narrator has left the building. What if I had a question? And I had so many questions.

The temptation here becomes great, irresistible, even—how can I write about these notebooks, full of travel spats with friends and the occasional hand job, without showing their contents? My mission all these years has been to know this person whom I cannot ever know, and here, finally, an opening: David, in his own words. It seems almost unfair to talk about the notebooks without sharing them, and for this reason, I have tried out every possible justification for quoting from them here. There is the nihilistic: he’s dead, he has no consciousness, he no longer exists to experience the humiliation and indignation of having his most private thoughts published and read by strangers. Then, on the exact opposite end of the spectrum, there is the mental gymnastics: he loved attention, craved the spotlight, and would’ve enjoyed having his words made celebrity, the mundane details of his life a source of interest for so many strangers.

I want to find these arguments convincing, and for brief moments, in conversation with friends or late at night at my desk, I can talk myself into accepting them. But before I get to the point where I transfer my uncle’s intimate thoughts from his pages to my own, an inconvenient feeling crowbars its way in. Sometimes it is thinking about facing my mother and telling her that I published her brother’s diaries—the ones she refused to read. Sometimes it is a physical feeling, the one you get when you receive a clear directive from your internal compass, then resolutely face the opposite direction and march ahead. And sometimes it is a simple realization: to publish my uncle’s diaries would be to sacrifice the privacy of a person who died young, who was robbed of longevity, and who is not here to defend himself. Perhaps David would have happily signed off on it; perhaps he would have made the same choice, if he were here to make it. But he is not here, and I cannot stomach taking advantage of his inability to object.

What I can do, though, is tell this story.

One day, visiting my grandparents’ apartment, I pulled David’s diaries from their home on the shelf, flipping absentmindedly through the notebooks as my grandmother finished a phone call in her study. A small, folded piece of paper fluttered from the pages, landing on the rug at my feet. I picked it up. It was a music request sheet from a party—a three-by-five-inch form that a partygoer might fill out and return to the DJ, requesting that they play a particular song. Instructions at the top identified the “mixtress” as Page Hodel, a legendary lesbian Bay Area DJ the Chronicle once called “San Francisco’s unofficial Pied Piper of Party.” The form was blank, unused—but on the back, someone had written something: a man’s name, address, and phone number, followed by a note: “When you don’t have to get up at 7 AM or whenever.”

In all my years of studying these notebooks, how had I never encountered this object? I punched the address into my phone and was disappointed but unsurprised to see that the map and an accompanying image of the street revealed only a nondescript apartment building about four stories high. Still, I squinted, looking back and forth between the fuzzy picture and the note in my hand. Someone had given David this exact slip of paper, the one I now held, and he had tucked it between the pages of this diary all those years ago. What had transpired with this person? Did they go home together to this tan brick building on Market Street? Did the man pass him the note on the dance floor—or at seven in the morning as David left for his job as a salesman at AT&T? I briefly considered calling the phone number, but of course I wouldn’t—that would be insane—and it almost certainly didn’t belong to the man anymore, the man who might very well be someone else’s long-gone uncle.

11: Fear of motion

I never knew this person. Why am I chasing him?

My mother reminds me that there is a natural human desire to know where we come from; to see our forebears; to search for our own thick eyebrows in theirs, the distinctive shapes of our noses, an unmistakable gait or familiar settling of the jowls. The recognition of ourselves in an ancestor offers both proof of our own existence and a logic for understanding it. You came from somewhere—you are not a lab experiment dropped out of space onto planet Earth, unmoored and without a history, but rather a link in a sequence, with a past that confirms your present. Someone came before you. And perhaps this someone with their crooked teeth, their widow’s peak—perhaps their existence explains yours in some way, provides a key with which to read your own map. “Then I think about my fear of motion,” the Indigo Girls sing, “which I never could explain / some other fool across the ocean years ago must have crashed his little airplane.”

Queer people my age were born into a unique kind of fortune. Our predecessors belonged to the first generation in which LGBTQ young adults came out en masse. Our aunts, uncles, and godparents grew up in the era of that famous and succinct Gay Liberation slogan, “Come out!” Many of them did; many of us grew up in families where someone was already out, already queer, had already named the thing before we were old enough to know it had a name. We were born, in other words, with the chance to see ourselves in our own families. Or tantalizingly close, anyway.

Is it any wonder I’m still seeking the airplane-crasher?

12: Debt

There is something else, too. My mother told me that David never had another boyfriend after his diagnosis—no one serious, anyway. She was quick to clarify that it wasn’t because of HIV, or at least, not because of the stigma. “I just don’t think he was in the right place emotionally to be in a relationship,” she explained.

I am younger than David when he died—barely. He did things I’ve never done: he moved across the country, traveled through Europe, went to business school. Some of them were not so happy: looking statistics in the face, he took out an expensive life insurance policy, a practical bounty on his head with my siblings and me listed as benefactors. The resulting inheritance paid for my college tuition.

I’m well aware, though, of the things I’ve done or might do that David won’t. I have the privilege of a relatively healthy body, for today. If I’m lucky, I’ll have children; if I’m lucky, I’ll turn 50; if I’m lucky, someday I’ll be the old person at the club, dancing even though I don’t know the song. Of course, none of us knows what will happen; all of this could change tomorrow. But for now, I live with the monumental fortune of being able to see my future. I don’t walk around like yesterday was an earthquake, and tomorrow could come another, and with it, the end of my existence. I do not live in fear.

I don’t know how to explain that I feel I have inherited an enormous debt, and maybe, also, a gift. When I dance for hours next to strangers and their pungent sweat; when I kiss a woman underneath a hundred gaudy rainbow ceiling ornaments in a West Village gay bar; when I lie on the beach for a deliciously long time and know I should put on sunscreen but can’t bring myself to reach for my bag. I know, logically, that these moments are not a gift from David, that he did not die so I could have them. But I feel, nonetheless, the achy weight of experiencing them in his stead. He no longer can, so I must. I owe it to him.

13: Cherries

My mother always tells me about how when he was little, David saved the cherries in his ice cream. He would collect them in his bowl, she says, waiting to eat them as the last part of his dessert. Sometimes, right as he got to the end, right as he was about to savor the cherries he had stockpiled, my grandfather would steal his bowl, teasing him. David never failed to get upset. It was cruel of my grandfather to play with him that way, my mom says. But sometimes she’ll also tell me that he was teaching David a lesson, and maybe not a bad one. Don’t be miserly with joy, I imagine that lesson to be. Don’t wait for a more perfect time to take pleasure in what you have.

I think about David and his cherries sometimes when I open my drawer, see that my favorite T-shirt is clean, and am tempted to save it for a different day. When I feel, for some reason, that I should wait and wear some other, lesser T-shirt. For what? I wear the shirt. It’ll fall to pieces whether or not I do.

14: Provincetown, one

One summer in my late twenties, my then-girlfriend and I decided to go on vacation to Provincetown.

Like many queer neighborhoods and towns, Provincetown was an artists’ community before it became known as a haven for gay people—my straight grandparents on my father’s side actually honeymooned there in 1949—but for decades now, it has been the closest thing in the United States to an official gay vacation town, replete with all the trappings of both gayborhoods and American beach destinations. In the summer, every coffee shop, art gallery, restaurant, and beach towel is filled with gay people (alongside a growing minority of straight tourists including, disturbingly, bachelorette parties).

My vacation with my girlfriend was far from my first time in Provincetown. As a child, I spent summers visiting Wellfleet, ten miles down the Cape. We took frequent day trips to Provincetown, eating pizza at Spiritus and free fudge samples at the penny candy store, reveling in the playfulness that, even as kids, we could feel in the air from the moment we biked onto the main drag. It was a beloved, magical place for me, and as an adult, I’ve wondered why. Are all children predisposed to love towns with weekly drag parades? (Maybe; after all, restrictive gender roles harm everyone, and children are perhaps more attuned to the pleasure of rejecting them than adults with many more years of repression under their belts.) I suspect, though, that I felt an instinctive safety there. I was always a gender-nonconforming child, always the source of visible confusion and the subject of barely whispered questions, always acutely aware that others saw me as strange from the time I was very, very small. My parents had many lesbian friends, women with strong muscles and handsome buzzcuts and impressive baseball skills, and I always felt drawn to them, even if I could not say why. Provincetown had the same inexplicable hearth-like quality. Something in me vibrated when I was there.

But visiting as an out queer adult was different—and as we drove into town on Route 6, the familiar bay-facing cottages coming into view, I thought for neither the first nor the last time about the fact that this was something David had done too. There is only one road onto the Cape. This row of little houses, the sun just beginning to threaten its descent behind them, would have greeted him on arrival, just as it greeted me.

David went to college in Boston and stayed in the city for several years after graduation. It was from there that he began to make the three-hour trek to Provincetown, on weekends and eventually for entire summers, which he funded by working in exchange for lodging. My mother still has his satin varsity jacket from the Boatslip, the raucous hotel and bar where he worked as a pool boy. The jacket is burgundy with white trim, an almost confusingly fancy staff uniform. My mom wears it occasionally on spring nights out on the town.

The Boatslip is still in operation, and every afternoon during the summer, it hosts Provincetown’s biggest party—the tea dance. If you happen to be outside at 4 PM, you witness its pull: on seemingly every block of town, a steady tide of people wanders toward 161 Commercial Street, settling in for three hours of boozy rum punches and dancing on the Boatslip’s deck overlooking the bay. The festivities end promptly at 7 PM, and the same ritual repeats in reverse, if more slowly: tipsy partiers in slim chino shorts and glittery drag costumes lollygag down the middle of Commercial Street, making the already-barely-car-friendly road just about impassable. They eat pizza at Spiritus, they go home to nap, they sit down for pasta at Ciro and Sal’s. Some of them will surface hours later at the A-House—a 200-year-old bar that’s sometimes described as the oldest gay bar in the United States.

This is a different Provincetown from the one I visited as a child. The proliferation of straight tourists and bachelorette parties aside, I never went to bars, drank cocktails, danced sweaty against any bare-torsoed men I didn’t know. On the first afternoon of our vacation, we went to the tea dance. It was an overcast day, and we were too early; we were new to this and didn’t realize that our 4:15 PM arrival was akin to a 9 PM appearance at a club. We ordered rum punches, and the bartender finished them off with extra glugs of Bacardi 151 down the straw. The line not yet clogged behind me, I told him my uncle once worked at this bar many years ago.

“Oh, have you looked for him in the staff pictures?” he asked me. “There’s one for every year inside.”

We ducked into the empty indoor bar to look. Some part of me had convinced myself that David’s employment at this exact establishment was a dream, that any proof that he had stood here would be purely in the form of stories I’d heard, not physical artifacts to be touched, held, or clung to. But there, hung along the stairwell leading to the bar’s hotel rooms, were framed group photos of the Boatslip staff, each neatly labeled with a year. I climbed the steps slowly, studying the pictures. In each, a crowd of some dozen men smile at the camera. They are handsome, young, fit. They wear staff T-shirts, some years burgundy, others pink. They ham it up for the camera, make goofy faces, lean on each other’s shoulders and sit at each other’s feet. As the photos get older—1993, 1992, 1991—the haircuts look more and more vintage, the clothing styles—tall white gym socks, tucked-in T-shirts with rolled sleeves—more and more resembling the photos I’ve seen of David. Many of these men are probably dead.

1983, 1982, 1981, 1980, then…nothing. I found myself at the top of the stairs, facing the hotel’s little reception window and a door labeled OFFICE. I looked at the hallway’s bare walls, a little frantic—did the photos continue in some unseen location? Was the rest of the display hung elsewhere? No, said the man in the reception window, wearing a blue Boatslip T-shirt. There might be older photos somewhere, he said, but he really couldn’t say. If they existed, they were probably in storage.

He didn’t offer to investigate further, and I didn’t ask. How could I justify such a request? I knew David worked here. My mother had the jacket to prove it, even if it was nowhere to be seen in these pictures. What more could I be seeking from a single group photo, one in which the total real estate taken up by my uncle’s face would have been smaller than the pad of my index finger? And perhaps it didn’t even exist; perhaps they hadn’t taken a photo that year, a negligent manager or grumpy staff. Perhaps it existed, and David wasn’t in it—he had been sick, maybe, or away on an overnight to Boston. I could not ask for an archival hunt for such a photo.

Why, though, did the absence feel so devastating?

I realized, back on the bar’s deck and feeling the rum punch’s depressive undertow, that I had allowed myself to anticipate something new—an addition to the static archive that I had assembled of David’s life. There had been no new stories about him for a long time; no new photos; no new facts to sit with, to run through my head during long train rides or jogs in the park. There were only the stories I asked my mother to tell me again and again, hoping that some heretofore untold detail might surface; the photos that I reexamined, searching the background for clues I hadn’t noticed before. When a person exits our physical world, so does the possibility of a new encounter with them. What we have is what we have; there is a bottom, and you can see it.

The staff picture was a trapdoor—a tiny, new piece of David to be discovered in a world he is long gone from. I longed to come face-to-face with him here; if a photo was my best chance, I would have taken it.

15: Yom Kippur eve

I call my grandmother and ask her if I can stop by to borrow David’s old journals; I need to check some facts, I say, make sure I’ve gotten the chronology right. She’s thrilled that I’ve asked. Of course, she says, she’ll have them ready for me when I come. A few days later, she tells me she’s putting together a collection of materials for me, stuff I’ve never seen. She thinks it’ll be useful for my work.

If I’m honest, I’m skeptical. Haven’t I spent decades of my life picking through every artifact of David that lives in their apartment? The photos, the old T-shirts, the childhood drawings, the elementary school report cards. The programs from the plays he acted in; the programs from his memorial; the photocopies of his obituary, Xeroxes of Xeroxes on which his face has been reduced to a collection of shadows, my grandmother’s familiar handwriting crawling in blue ink—“Bay Area Reporter”—across the top of the page.

But my grandmother has the best memory in our family, and she is always surprising us. I go with an open mind, and at the end of our visit, as I am leaving their apartment, she proudly instructs my grandfather to hand me the tote bag that she has hung by the door. The bag is stuffed with loose papers of different sizes and thicknesses, envelopes, folders, cards. I check to make sure the journals are there, then drop the bag into my backpack and buckle it closed.

Back home, I sit on my couch and pull papers from the bag, spreading them across the coffee table. My grandmother is right; I haven’t seen any of this before. The bulk of the contents turn out to be condolence cards that my grandparents received after David’s death. Some are long, and the words, despite the authors’ insistence that none could be adequate, strike me in their empathy. “I grope to say something, anything that could relieve some of your pain and suffering,” one person writes. “We press very close to you with all our sympathy and with love.” Others are far briefer; some writers, in a move that scandalizes me, have only signed their names beneath the greeting card’s preprinted message of sympathy. All of the condolences have been marked with a short notation in my grandfather’s neat European script, a detail that escapes my notice until I realize that it appears uniformly on each of them. “Answered,” he has written at the top of every card, followed by a date.

I finish the stack of cards and am about to turn my attention to the journals when I notice a five-by-eight spiral-bound notebook with a plain cardboard cover, a notebook I’m sure I haven’t seen before. I open it. The first page bears a centered inscription, written in the elegant letters that have become familiar to me: “Purchased Greenwich Village, NY. 10/12/86. Yom Kippur eve.”

Ah, I think. Maybe this was a notebook, like so many of my own, bought with lofty intentions of diligent daily journaling and never used. Maybe that’s why I’ve never seen it.

But I flip the page, and the first lines shock:

6/12 started Septra

6/13 headache in AM took aspirin

6/14 headache took aspirin 2 doses

6/ started AZT

Among the many records of David’s life in his journals—his birthday lists, his travel stories, his New Year’s resolutions, his records of every dollar spent, every cocktail enjoyed—there is no mention of AIDS. The conspicuity of this omission becomes more and more apparent as I repeat the revelation to myself, which is somehow only occurring to me now, scanning this meticulous documentation of headaches and pills. No mention among the accounts of arguments with friends and lists of concerts. No mention among the recounting of flights and ferries, among the favorite movies and musicals enumerated. How could I have been so naive as not to notice—not to see the glaring absence, the obvious missing shadow of that phone call from his doctor’s office in June 1987, and all that followed it? Here, finally, they had surfaced: the missing pages.

16: Was he brave?

“Nana,” I ask my grandmother. “Will you tell me the story about David getting bullied on the train platform?”

She laughs.

“Well,” she says, never one to turn down the chance to tell a story. “You mean when those little boys held him up?”

She tells me again, every detail. How she and David had been riding the subway home together in the evening, and how he said he wanted to get off early to buy a book. How she didn’t think twice about it—he was just twelve, but he already rode the subway to school by himself every day. How she gave him ten dollars, and how an hour later, a police officer called to tell her that he had her son. The officer said that he was going uptown and could drop David off, but my grandmother said she would collect him herself. She did, and on the way home, he told her how two little boys had tried to take his money.

(Little boys, my grandmother calls them, and here I remember that this is always part of the telling: how young all three boys were, how ridiculous the idea of little boys mugging each other.)

He’d refused to give them the ten dollars, and they’d argued with him all the way into the train station, where they passed the better part of an hour threatening him with a tiny penknife until he cried, and then pretending to comfort him whenever strangers walked by. All the while, he remained steadfast in his unwillingness to give up his money. Finally, a police officer happened upon them and intervened. He brought all three boys back to the station and summoned their mothers to retrieve them.

“I admire him for it,” my grandmother says at one point, using the present tense to describe his refusal to give in. I press her.

“Do you think he was brave?” I ask. “I mean, wasn’t that brave of him?” I am testing a thesis now. It is about David, but it is also about me—about the boys who stole my school pictures in middle school and scrawled epithets on them before taping them up in the hallways; about the girls who surrounded me in the schoolyard and told me I looked like a monkey to a chorus of laughter. I would have been exactly the age David was as he stood on the subway platform, fingers closed around the bills in his pocket as the trains came and left, came and left. Haven’t they made us tougher, all the little boys who held us up with tiny penknives? Aren’t we braver for our trials on the subway platforms, even if we cried, even if we grew desperate as the hour wore on and it seemed no one was coming to help?

“I don’t know if he was brave,” my grandmother says. She never gives me easy answers, for which I am grateful. “I think what’s shocking is that no one stopped—in that whole hour, all those adults, walking back and forth, and nobody noticed what was happening with those little boys.” She shakes her head, and we are quiet.

“I miss him so much,” she says, shaking her head. “Still. Such a schnookiepuss.”

Schnookiepuss. A word I grew up with; a word we loved to hear from our grandparents. If we were flowers, we would’ve bent toward the sound every time it fell from their lips. If I had to define it, it’d be this: a schnookiepuss is someone who is lovable. Except it’s not an abstract kind of lovability. A schnookiepuss is a particular someone who you just love so much.

I think then about what I know of David’s last trip to Argentina, right before he died. How at a McDonald’s, he followed a man who had cruised him into a bathroom and dropped his pants for a blowjob. The man flashed a knife and took all of the cash he had. His friends, telling me the story twenty-five years later at a dinner party in San Francisco, laugh. It’s a story of a hookup gone wrong, and from the way they describe him when he came out of the bathroom, it doesn’t sound like he was brave. I think they use the word hysterical. I would’ve been hysterical too.

So, maybe not brave. Stubborn? And determined; if he was hysterical, he didn’t let it get in his way. The bathroom holdup was not the event that sent him on an early plane back to New York, and I feel reasonably certain that if he had lived, he would have kept on cruising. I think about the child on the train platform, surrounded, and the thirty-seven-year-old flying home to die. My grandmother: nobody noticed what was happening with those little boys. A bathroom, a penknife, an earthquake, a virus. So many passersby. Sometimes I feel so angry.

17: Provincetown, two

Toward the end of my week in Provincetown, the Boatslip hosted Solid Gold—their twice-weekly party paying homage to the eighties television show of the same name. Madonna, Whitney Houston, Cyndi Lauper, and Prince floated across the open-air dance floor. An overcast day, the sky striated and gray behind the bare masts of sailboats sitting low in the bay, but who would complain? Even though it was Thursday, the bar was full, and all around us, men in tank tops and one middle-aged lesbian bachelorette party—having, I noted, perhaps the best time of anyone in a sea of good times—jumped euphorically with, or more or less near, the beat. When the familiar opening notes of “It’s Raining Men” rolled from the speakers, a collective cheer spread through the crowd, and at the chorus, every person sang along, their feet stomping on the bar’s old wooden floorboards with synchronized thuds that almost drowned out the song’s percussion track. “It’s raining men,” we all shouted, “amen,” and the air itself seemed to vibrate with pleasure.

Then the next song began: a quintessential eighties beat, a synth melody, and an unmistakable voice. “Ooh yeah,” Whitney Houston riffed, as “I Wanna Dance with Somebody” played.

“I Wanna Dance with Somebody” came out in 1987, the year I was born and the year David was diagnosed with HIV. It’s a song that has always buzzed somewhere underneath my ribcage; a resonance I attribute to the fact that, like so many ostensibly straight songs adopted by queer people as anthems, the song manages to express something profound about queer longing.

The pain of the gap between what we have and what we want is at the heart of “I Wanna Dance With Somebody.” Yet, it’s not a sad song. Whitney makes the choice to believe in desire, even when the deck feels stacked against her—even when desire might bring her pain. It’s a choice she has to make if she’s going to survive. The song is melancholy, but it’s not cynical. It’s not a mourner’s lament. It’s a manifesto, a celebration.

Most of the time, for me, the gulf between the living and the dead feels vast and uncrossable. Very rarely, though, things line up. The physical landscape, the one that keeps the records as we humans change shifts, offers up the memories it’s been holding safe in its files. A bar plays the same song they played thirty years ago. They serve the same potent rum punches they’ve been serving for thirty years. Dancers’ feet stamp out rhythms on old floorboards that have seen the same rhythms before. The sun sets pink and orange over the boats in the bay, just as it’s always done. The only thing that’s changed is the year on the calendar, and for an instant, I feel like all that separates me from someone who died decades ago is a sliver of time and space, a gap no larger than the one between the sun’s last flash on the horizon and the moment it dips out of sight.

18: David

How has it taken me until now to realize? In Hebrew, the name means beloved.

19: To make sense

Contrary to my speculation that perhaps David’s Yom Kippur notebook would turn out to be an empty one, every page is filled. It reads, today, a bit like the notes of a person who has spent a weekend falling down an Internet rabbit hole of everything that was known in 1987 about AIDS. It includes documentation of symptoms, questions for doctor’s visits, notes from doctor’s visits, book recommendations. Lists of drugs, mini-lessons in virology, references to studies and legislation. Names, phone numbers, addresses, organizations. Dates. It is detailed, comprehensive, at turns both erratic and thorough. It has an unmistakably frantic tone. It is almost unbearably painful to read.

These pages, I realize, date from the same time as all of those vacation diaries. He would have sat on that plane to Brussels, the one whose ticket is still tucked into his journal, with two notebooks on his tray table: the one in which he carefully documented the flight, how much he slept, the museums he was looking forward to visiting, and this one: the one in which he kept track of questions he wanted to ask his doctor, raised spots on his skin, phone numbers for support groups. I am tempted to tell a story about this divide. Was he compartmentalizing? Was this how he maintained his sanity—walling off the fear from the joy? The separation is so complete that it is hard to imagine it is an accident. But, what do I know about how David lived? What do I know about the air aboard that plane? I’m an amateur detective, like a child with a polyester Sherlock Holmes hat and a giant magnifying glass, its plastic lens cloudy and scratched. I’m fishing, and if I stumble upon the truth in the process, I won’t even know it. There’s no one to tell me I’ve gotten this right.

I turn the pages and pause at each one, turning each phrase in David’s handwriting over in my head—pentamidine, acyclovir—as though, if I concentrate, any one of these words could be a portal to the past. Simonton Getting Well Again (visualization). As though, if I find out what books he was reading, maybe I’ll be transported back to that apartment on 17th Street. AIDS + ARC, amantadine, rimantadine, HPA23. As though, if I squint hard enough at his words, maybe I’ll finally see him at his kitchen table, on the bus, in the doctor’s waiting room. Trying to make sense of something no one has made sense of yet; trying to figure out how to live.

I make my way through the entire notebook, writing down terms and bullet points as I go. Retrovirus RNA->DNA->RNA sends me back to the unit on HIV in middle school biology, a class I took six years after David’s death and, to this day, the only time I have ever gotten a good grade in science. Ribavirin, azidothymidine AZT, and I think about my grandmother telling me how David, weakened by antivirals, struggled to lift their suitcases into the overhead compartments when they took a plane together to Hawaii. Dideoxycytidine TOXIC. Naltrexone immunostimulating NY study. Peptide T? Candace Pert, Salk vaccine encouraging. FDA testing Van de Kamp, Agnos not passed, Doolittle killed, Theresa Crenshaw, Randy Shilts’ book this month The Band Played On. 20% infected in ’82-83 are stable. Pentamidine inhalation prophylaxis/Septra, why not try it. On, and on, and on.

A photo is tucked about three-quarters of the way through the notebook, on a page that begins with a list in green marker: medical, chg pent appt, Conant appt, East Bay recom. It is me as a toddler, stepping confidently forward on the cracked sidewalk in front of my Brooklyn home while my mother, laughing as she looks into the camera, stoops to reach for my hand. The trees are bare, but it is a sunny day. The photo gleams with happiness.

I try to remind myself that the chances are good that my grandmother absentmindedly stowed this photo in these pages years after David died. But the type on the back of the picture announces that it was printed by a photo lab in February 1989. It is possible, I decide, that he placed it here.

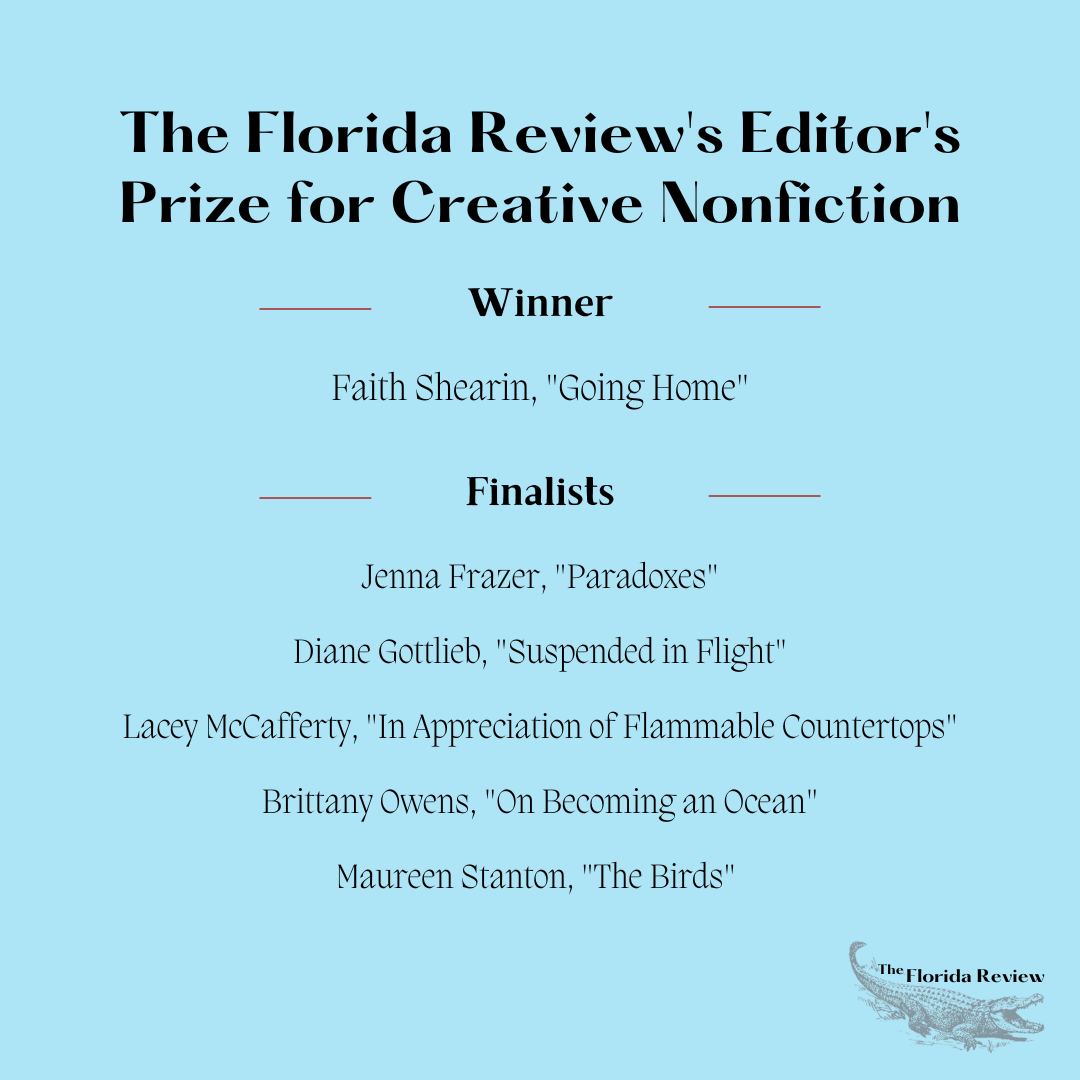

“Lost Uncle” originally appeared in The Florida Review vol. 48.1, Fall 2024, available for purchase here.