Professor Wyckhuis would stand at the front of the classroom and lecture, his gaunt face tilted to the podium, his bare scalp growing red with fervor. He’d occasionally whirl toward the board behind him and scribble out etymologies, the chalk popping and splintering in his hand.

After class I’d join him for coffee in the Union. He would smoke cigarettes and touch his stout mustache and gently answer my questions about the Platonists and the Church Fathers, or describe his own scholarly projects: translations of commentaries by obscure saints and monks and mystics.

I once confessed to him that I was given to daydreaming, to making stories, and he, in a typically tender gesture, proposed that I might think of it as prayer and submit gratefully to it. We were walking beneath the trees of the quad, and he explained that the imagination might be exercised to understand our fears, and delight in the works of God, and grieve for our sins.

“Then,” he said, “if our devotion is deepened, and our minds not scattered, we may be called to the contemplative life.” He bowed his head and briefly closed his eyes to recite the words of—he later told me—a French parish priest, speaking so softly that I had to lean toward him. “The interior life is like a sea of love, in which the soul is plunged, and is drowned in love.” And then he opened his eyes and looked at me. “Just as a mother holds her child’s face in her hands to cover it with kisses, so does God hold the devout man.”

The story was that he’d left the priesthood in order to marry, his eyes still wetting with emotion whenever he’d speak of his wife, an elementary school teacher from Missouri, who’d passed from this earth twenty years before.

And there was also a competing and more dramatic story, that his wife had been a French girl, whom he’d impregnated when she was still at the lycée. It was then that he’d left the Church and married, and it was shortly afterwards that she and the baby died, the new bride hemorrhaging during childbirth, the infant’s neck bound with the umbilical cord.

If true, did he blame himself for the deaths of the schoolteacher or the French girl and the innocent child for whom he’d given up God, and whom God, in a show of spite and bile, cast to dust?

A reckless undergraduate was said to have mentioned the rumors to him, and he was reported to have smiled and said, “Charming,” and then, touching the student’s sleeve, “It is of course always easier to love the dead than the living.”

He once admitted to me that he’d stopped on the way home from campus the night before to buy a copy of Playboy. “I was angry,” he said, nodding his head. “I was very angry with God.” He crushed out his cigarette in the ashtray upon the cafeteria table. “So then,” he said, his jaw thrust forward, and he shook his fist in the air.

Once, late at night, Greta and I were leaving a party at a house just off campus, and we saw him walking slowly along the dim sidewalk across the street, in the direction of his own house, two or three blocks away. Twice he stumbled, the second time falling to his knees.

“Oh, Joe,” Greta said, and we started toward him, but one of the hosts of the party, a graduate student, who was standing on the lawn and talking to some girls, said, “I’ll get him,” and trotted across the street, helped him up, and then, his arm around the old professor’s shoulder, escorted him home.

There was a small memorial service for Professor Wyckhuis in January of my senior year. His body had already been flown to Antwerp, where a lone surviving brother was to bury him. As Greta and I stood in the dim chapel near campus, I felt thin and frightened, as if I’d been scooped out.

“Joe?” I could hear Greta’s whisper at my shoulder, feel her hand on my arm.

Later, outside in the glare of the winter sun, she told me that I’d begun to whine, a sound so slight and high pitched that she at first become aware of it only at the breaking of her own breath.

When he heard I was engaged, Professor Wyckhuis told me not to enter into marriage easily. He said that only those who’ve never been married or are destined for divorce think that they’ll not tolerate woundings or pain. I could smell tobacco on his sweater as he sat near me, clenching his hands. “It is like faith,” he said. “Some do not understand the necessary agony of the relationship with God, and so their faith . . . ,” and he suddenly splayed his fingers, like an object scattering.

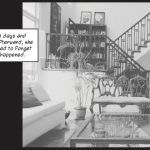

His brother had directed that his personal property be given away or destroyed. And so in rounds—faculty colleagues, graduate students, and then undergraduates—we strolled through his house—polite shoppers at an abandoned flea market—bending to examine books, peering into dark closets, smoky with old sweaters, glancing at the chipped china in the kitchen, looking for something to take with us.

Everyone stepped softly past the bathroom. Devil’s madness.

The walls in the living room and bedroom were yellowed and bare, the dresser and table tops white with dust. I stood before his narrow bed and picked up from the pillow his glasses, the gold spindly frames, the lenses smudged, the nose pads mossy with oil and skin.

And then my face began to ache, as if I’d been struck, and I left his house without taking anything.

During the time that I knew him, Professor Wyckhuis battled insomnia. We rarely spoke about it, but I’d sometimes notice a weary edginess as we had coffee, as he answered my questions, sometimes struggling to recall a name or find a word.

“Have you seen a doctor?” I would ask.

“Yes, yes,“ he would say, nodding, and he’d shrug. “But it is the cigarettes, I think.” Or he’d simply smile and recall the words of some medieval monk. “Suffering is short pain and long joy,” he’d say.

Once, during the fall of my senior year, he stopped me on the quad and gave me a copy of his latest book, a translation of The Cloud of Unknowing. He offered it to me and then bowed. “A gift,” he said.

On the title page he had written, in his small, cramped hand, “To Joseph, Thank you for your spiritual help in the past. I wish you the best always: Deus providebit.”

When Greta became pregnant, she and I would walk the small Kansas town to which we’d moved, out to a graveyard on its north edge, five flat acres in a pocket of mulberry trees. It was there that we decided upon the name Hannah. We’d been taken with the tall and graceful headstone of a woman named Hannah Jane Flax, who was born in 1859 and died in 1947, and who was surrounded by family members, some—a husband, two children, and a grandchild—preceding her there, all now lying peacefully beneath blizzards and droughts, removed from the welter of the world. Greta saw her in those terms—a life lived deeply and then the serene and slow re-absorption into the earth. I tried to reckon the anger and the grief of those left living, that which had been loosed over the years on these few acres, the weight of accumulated mourning, still, surely, in the air, the damp of it on our skin.

I labor at forgiveness, thinking of Professor Wyckhuis’s instruction, his quoting of Francis of Paola, that the recollection of injury adds to our anger and nurtures our sin. “It is,” he said, touching his breast, “a rusty arrow and poison for the soul.”

He once told me that Qoheleth, delivering one of most brutally honest books in the Bible, revealed that traditional wisdom has failed, that we can’t know God, that we lack control, and that life is short and death certain. “However,” he said, crouching, bending close to the surface of the cafeteria table, his fingers poised as if to pluck from it a crumb of bread, “joy can still come to us in small portions.” And he looked up at me and smiled. “We need to be attentive.”

The story was that Professor Wyckhuis’s landlady found him dead in his bathtub, three days after Christmas. In the wastebasket were, supposedly, empty bottles of lorazepam and Tylenol and a spent blister pack of Sudafed. On the bath mat was a half-full three liter bottle of Rosso di Montalcino. His wine glass wavered on the bottom of the tub, between his legs, beneath the skin of cold water.

The story was that at the beginning of his last final exam in December, he wrote upon the board, Faith is the agent of things un-hoped for, as the thief proved. And the students laughed, and he winked and wished them luck, and left the room, and the building, a graduate student arriving to proctor and pick up papers. And no one on campus ever saw him again.