A couch was to the left, the bed place to the right;

my writing desk and the chronometers’ table faced the door.

—Joseph Conrad, “The Secret Sharer”

We’d been talking at the bar for a while when she finally told me her name, Angela. “It’s Angel with an extra A, for attitude.” She heaved forward in a laugh, a dark sheet of hair whipping over her face. Silver jewelry glinted in the blur.

“Great mnemonic. I learned a lot of them on the Tammy Sue.”

“So was the trip worth it? Research-wise, I mean.” She arched one eyebrow, as dark and precise as a swoop of calligraphy.

I wasn’t sure what to say. Already, my experiences aboard the Tammy Sue—the tense silence of the night watch, the sudden squalls, the odd sense of being outside of time when we were on open water—seemed on the cusp of dissipating, as if they’d never occurred. I’d recorded extensive notes, but I had trouble capturing how close I’d felt to Conrad, how oddly serene I’d been as rain pelted my foul-weather gear. This sensation, I’d noted at the time, was like that of a man in possession of a beautiful idea, impervious and even invigorated by the inevitable cascade of doubts. But now, back on land, I could hardly remember the feeling.

“It was extremely fruitful.” I lowered my voice in an effort to sound more certain. “I understand Conrad’s work much better, especially his use of his first command, the Otago, as a metaphor for time, social class, the body, relationships—”

“You know what? You’d love my son Eli’s work.” She handed me a pamphlet from a box at her feet. Sun-faded and curled at the corners from humidity, it featured a smudgy watercolor boat and a photo of a dark-eyed young man staring at the camera through a ship-in-bottle held up to his face.

“He does them all. Galleons, barkentines, schooners—he’s crazy about boats. Go to almost any harbor on the East Coast, if there’s a sailing ship hauling tourists, you’ll find Eli’s ships in the gift shop. She reached over and unfolded the pamphlet. “Just read the description. He’s a true artist.”

Serenity Ships: Sail into Your Dreams!

Each Serenity Ship-in-bottle is custom handmade work of art, precisely scaled, using only the finest authentic materials,

including teak, steel, brass, copper, fiberglass, sisal, hemp, and a number of exotic woods upon request.

The bottles are hand blown and every ship sails forever on a sea of diachronic glass, which sparkles with the dynamism of sun-streaked waves.

We can create any ship—from miniatures of real vessels to fanciful ships seen only in the mind’s eye—

and bottle their aesthetic and emotional power for evermore.

Look in my bottles and feel yourself swayed by the light chop of dreams.

When I looked up, Angela was arranging several ships in bottles along the bar. They were small—no bigger than my thumb—and each was attached to a silver chain.

“You’re going to love what I brought today, Simon,” she said to the drunkard at the corner of the bar, sliding a bottle toward him. He pressed his eye to it and made swooshing sounds to mimic waves splashing on the tiny boat. “Damn, it looks just like my uncle’s old shrimp boat, Lorilei. How’d Eli even know—?”

A heavy-built tattooed woman let the door to the kitchen swing closed behind her and headed toward us. Angela turned to me and whispered. “Check it out. She’s famous for insulting customers.”

The wall behind the bar was jammed with crude hand-painted signs, full of boozy epigrams and boasts. The largest sign—Gloria Be Thy Name!—was surrounded by dozens of caricatures of Gloria, all depicting her as a spiritual figure—sitting on a cloud with a cocktail shaker, plucking a feather off her angel wings to garnish a drink, anointing a drunk with a whiskey bottle. A poster of a man with missing front teeth had a small sign beneath it: Snapped his fingers to ask for a refill.

“What’s this?” Gloria slid over to us, leaning over the bar, taking in the lined-up bottles then fixing her eyes on me. Her head was shaved except for a bleach blond swath drawn up in a high ponytail.

“Gloria, meet Julian. He’s a scholar and a sailor. He was just at sea, part of his research.”

“At sea. Of course. Looks a little wet behind the ears —”

“Gloria,” Angela cut her off. “How ’bout a Briny Squall for Julian?”

“A fine idea,” Gloria said. She came back with a large glass, swirling with dark liquid and what looked like flecks of gold. The rim was salted and garnished with a single desiccated lime. It spilled as she plopped it on the bar.

“The world famous Briny Squall.”

The drink rolled down my throat as if it were a syrup vapor, like nothing I’d ever tasted. I hardly needed to swallow and a full one-third of the drink was gone.

“Please. Just have a look,” Angela prompted, sweeping her hand above the tiny bottles on the bar. I picked up the closest one, the Golden Hind. I expected a crude plastic jumble, but the ship was so finely detailed and scaled that I thought at first it was a line drawing pasted to the back. As I turned the bottle, the shadows of the sails and spars moved across the deck.

The hull was constructed of the thinnest slivers of wood, bent and notched and shaped into an uncanny replica. The sails resembled silk, with edges that appeared finished—though I could not detect a single stitch of thread. All the lines of a real galleon were there, but they were cobweb-thin and translucent, only manifesting when the light hit a certain way. A crow’s nest, smaller than a ladybug’s shell, was dark and swirled as if shaped from the smallest piece of burl wood. A jagged pattern, like the profiles of faces, edged the bowsprit. The galleon sat in dab of blue glass so pale that I could see a deepening field of bubbles.

I pulled the bottle away from my eye. All the shapes around me appeared huge and undefined, as if I were peering through a smudged telescope. I blinked twice and everything returned to normal proportions.

“Amazing? Am I right?”

“They are…” Tiny winches, portlights, locker latches, even the compass cards were rendered with exquisite accuracy. I could detect only one tiny flaw when the boats were level on the bar. Each horizon was askew. Not one of the boats floated on its proper plane. Old Ironsides tilted slightly forward; Pride of Baltimore listed to port; the clipper Flying Cloud was weighed down unnaturally in the stern. Somehow this small defect made the ships even more alluring.

“Oops, one more.” Her focus shifted to the smooth crease between her breasts, where several silver chains terminated in the neckline of her plum-colored dress. She pulled one of the necklaces over her head and handed it to me. The bottle on it still held the warmth of her body. I lifted it up to the light to get a better look. It was the barkentine Otago, Conrad’s ship, the name clearly stenciled on the bow.

“Amazing…” I muttered as I stared into the bottle.

“Is that the one you were talking about?”

“It is.” Like the others, it was rendered perfectly—and it floated, only slightly cocked, on a perfectly still sea. I could almost sense the slow, almost imperceptible heaving under her hull as Conrad and his crew drifted on the windless South China Sea.

“All his ships are completely authentic. Even the interior stuff that can barely be seen with the naked eye.”

“It’s a beautiful rendering of the exterior.” I said. “But I hope you’ll forgive me for saying that no one can faithfully recreate the Otago’s interior plan, at least not when Conrad sailed her. This I know for sure.”

There exists only one good photo of the Otago, a blurry image of her under sail near Australia. Her salvaged helm adorns a museum ship in London, and what is left of her hull lies rusting in New Zealand, but the interior arrangements of the Otago have baffled Conrad scholars for years. My mentor, Dr. Marvin Kendricks, long maintained that the labyrinth of rooms and passageways within the Otago helped shape Conrad’s notion of human psychology. In fact, Kendrick’s unpublished paper described how the stowaway “secret self” in the “The Secret Sharer” was actually Conrad’s id flitting around the frontal lobe, trying to avoid discovery.

“Well,” Angela stirred her drink. “You might be surprised. Eli’s ships are like nothing else you’ve known—flawless, and not a detail left unfinished. Maritime museums all over the world have his number on speed-dial. I bet he knows the Otago inside and out.”

I took a sip, not wanting to offend her with my skepticism. And, of course, it was possible Eli had stumbled on some obscure maritime records, information that might guarantee my dissertation would leave a mark. I’d heard stories—Kendricks sometimes told them—about scholars who would find paradigm-shifting research in the most unexpected places. Interviews with elderly neighbors of a canonical author. Old letters hidden in a barn loft. Brilliant marginalia languishing in a box of deaccessioned books. The fact that she had a replica of the Otago could be a sign.

“You should come meet Eli. He works a boat show in Jacksonville every Monday. I can take you there tomorrow.” She opened the chain in her hands and leaned forward, placing it over my head. “It’s meant to be worn.”

—

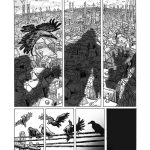

A heavy after-rain fog hovered in front of me, cleaving as I walked to the waterfront park across the street. I relieved myself behind a bush and teetered a bit when I zipped up my pants. The St. Marys River was calm and empty—just like the sea Conrad describes in “The Secret Sharer.” I tried to picture the Otago in the grips of such stillness. I pulled the miniature out from under my shirt and held it in front of my eye, lining up its hull with the real horizon behind it. The ship was luminous against the moonlight, each of its filament lines lit up. My vertigo transferred to the boat, which began to bob in its glass swell. A small yellow shape flicked up out of the crow’s nest. The tip of my thumb slipped into a small divot in the base of the bottle as I turned it to get a better look.

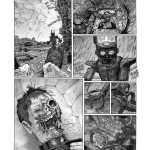

Startled by footsteps from behind, I turned to see the silhouette of a man, no bigger than a toddler. The next thing I saw was his pipe—a wild squiggle of burlwood with a hot coal pulsing in the bowl. A fine mist of what smelled like seawater—salt, fish, seaweed—burst forth with each puff. He stepped into the moonlight, illuminating his yellow sailor’s suit and the metal eyelets of his leather, lace-up boots. His face was cramped, wizened; his crow’s feet ran down his cheeks and pushed up against the accordion folds of his smile-lines. His irises, as he met my eyes, were a shifting shade of blue, turning from nearly white to deep navy as if they were portholes to a sea behind him.

I reached out, but he jumped back and gave a tsk-tsk motion with one finger. There was something familiar about him. I blinked once, expecting him to vanish, and it hit me. He was a color version of a woodcut I’d seen in a book titled Legends and Superstitions of the Sea. He was a kobold, a sprite of German folklore meant to assist sailors at sea. How curious, I thought. Just another specter of my thesis research, conjured from whatever chemicals circulated in my nervous system. The sea-going kobold had a special name…what was it?

The kobold coughed and small iridescent flakes issued from his nose. A few landed on my hand. Fish scales. He drew a piece of gray netting from his breast pocket and wiped his nose.

—

“Orange garbage bag by a mile-marker sign. Gets me every time.”

My body was shaking as I awoke. The side of my head was resting on the passenger window; the thick glass vibrated and blurred my vision. At first I thought I was still on the Tammy Sue, waking up for early morning watch, but then I saw the mirror of the Volvo and a slice of moving highway in its view. Angela’s voice startled me when she spoke again.

“See that orange bag? State-issued. Makes me think of this guy I dated, Owen.”

The sun was just edging above the clouds, and a bright glare from the west intermittently blasted out the view through the windshield. Auroras blurred the edge of my vision. I dropped my head and rubbed the back of my neck as Angela explained how she and Owen met on a highway cleaning crew. They’d tried to stab the same fast-food bag with their trash pickers, met each other’s eyes, and laughed. “And that’s how the whole Owen mess began…”

She hit the accelerator and swung into the passing lane. Every few minutes, something along the road would remind her of another man who’d come and gone from her life. A billboard for a Christmas décor depot reminded her of T.J. and his cat, Glinda, who needed emergency surgery for eating tinsel—something Angela had to pay for, the mooch. I nodded, trying to follow, but her voice soon faded out. My worn copy of Norbert Sherwood’s seminal Conrad Adrift was lying open and face-down on the floor. I flicked through the pages, causing Kendricks’ accusing marginalia to shudder and twist like a flipbook cartoon.

“And then guess what Crater did? Just guess?” Angela voice got louder and higher, and it seemed perilous not to follow what she was saying. “He left me for Uma Kline, that meth-head farmer.”

“You had a boyfriend named Crater?”

“Yes. Suited him. The asshole.”

“I’m sure Eli understands. You might have made a few bad choices, but no one is perfect,” I finally said, trying to respond to the main theme of Angela’s story—how each one of these failed father figures had driven Eli deeper into his ships-in-bottles, and further from her.

“Shit, AC’s out.”

Angela went quiet as she turned the car’s blower knob, cocking her ear toward it, as if trying to unlock a safe. I was glad for the break. That morning, I’d awakened to the sound of Angela knocking on my hotel room door, with no recollection of getting there. One of a dozen rooms in the clapboard hotel next to the bar, it was a small, slightly grimy space stuffed with antiques apparently plucked from the curbs of St. Marys. I’d never blacked out drinking before, and the morning felt like a fragment chipped away from the rest of my life.

“I look forward to meeting Eli,” I said, rubbing my eyes. “I’m sure Kendricks would like to hear about him too. And if he knows as much as you say he does, he’d get a prominent mention in my acknowledgements, at the very least.” I checked my watch, four p.m. London time. “Do you mind if I call Kendricks?”

My cell phone worked poorly ever since leaving the Tammy Sue—the captain said the salt air wreaked havoc with circuitry. Kendricks was inscrutable face to face, but 4,000 miles away through a salt-soaked phone, he was barely intelligible. He’d just presented a paper on Conrad’s “Chance” using babushka dolls as an organizing metaphor (“The dolls are stories in stories. The dolls are repressed selves within repressed selves. The dolls are meta.”) It had gotten a cold reception.

“Oh, so now every carnival barker thinks he’s a Conrad scholar,” Kendricks sighed when I told him about Eli’s Otago, “as if the field wasn’t already crowded with clowns and charlatans.”

Kendricks was in one of his moods, I could tell. It was probably best to save talking about the Otago until he cooled down. I changed the subject. Kendricks had an encyclopaedic mind for sailing folklore, so I told him about the kobold in my dream. The line was silent for such a long time that I thought I’d lost the connection.

“How well do you know this woman, this…Angela?”

I glanced at Angela, who was picking at something in her teeth.

“I met her at The Eagle’s Nest, a sailor’s tavern in St. Marys. She’s great.” The words were out of my mouth before I’d realized what I’d said. Angela smiled, ever so slightly, but kept her eyes on the road.

“A bar? The fishing boat stint was your chance to get a true sense of the sea. Now you’re talking about toy ships and bar floozies and a damn Klabautermann—that’s the kobold you’re describing, by the way—and I don’t hear a word about your dissertation’s progress. You’ve got to stay focused. Remember what happened to Nathan? All it took for him to abandon his work was Sherwood leaving that singed puppy dog on his doorstep…You’ve got a target on your back now.”

I’d heard all this before. Whenever Kendricks was upset, he’d talk about Nathan, his lost superstar student. Nathan had become so involved in caring for a burned puppy that he dropped out mid-semester to work at a pug rehab center. He never came back. Kendricks maintained that one of his rivals—Sherwood, he assumed—had planted the maimed puppy on Nathan’s doorstep to ruin Kendricks’ chances of having a star protégée. I hated when he brought Nathan up. It made me think that he was the true nadir of Kendricks’ mentorship, and that I was just a pale second act. I shook away the thought. Kendricks was just tired and upset.

“Everything is fine, Dr. Kendricks. I’m fine. Wait until I tell you what I saw on the Tammy Sue. The boat had a rope ladder just like the one in the ‘The Secret Sharer,’ and it made me think about how Conrad disorders his narrator’s perceptions—”

“Just be careful. Don’t leave your drinks unattended. And call me if anything… goddammit.” A sound of shattering glasses and a chorus of cussing and voices overwhelmed the line. Kendricks came back on, panting. “Goddamn cheap limey glasses! You can bleed in a bar over here and no one cares! Hey, Redcoat, can I get a damn rag?”

The line went dead.

—

Traffic piled up as we approached Jacksonville, and the Volvo kept stalling out as we idled, creeping forward every five minutes or so. Up ahead, cars were slowing down and stopping as they reached the margins of a growing traffic jam. Angela hit the brakes suddenly and swore as the back of a pickup truck seemed to rise up to meet us. Cars in the left lane whizzed past us, then slowed and stopped.

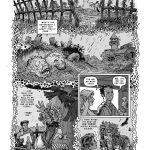

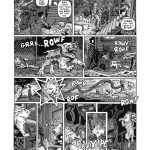

A green sedan idled in the right lane, its window lined up with mine. At first, the car seemed to be empty except for the driver, a harried-looking church matron with a grim, forward-facing expression. But as I gazed in the car, the muted leopard print of her cardigan swirled and resolved into the kobold’s small, hunched body. I blinked and the kobold’s face was pressed against the window—mashed, really—as if he were some kid mugging for his friend. The window flattened his lips as he rolled his face to the side so I could see him wink. Then he ducked from view.

A small square of fabric slowly rose up in his place. A thin wooden stick followed; it was a small flag divided diagonally into two colors, one half yellow, one half blue. I immediately recognized it as an international maritime signal flag, but I had to think for a moment before I could identify which one. It was the Kilo flag: I wish to communicate with you.

The flag lowered and the kobold’s face appeared, his eyes on mine. His blue irises curled up like an old Japanese print of a wave, his pupil tucked in like a surfer. His face was wan and his smile lines loose. I nodded, since he seemed to be waiting for a reaction.

Now he lifted a simple blue flag with a white cross above his head and wiggled it. Not one I recognized. I reached toward the back seat, grabbed the maritime signs and signals book from my bag, and flipped through it, my hands shaking. Stop carrying out your intentions and watch for my signals.

The line of traffic shifted and we shot forward. I put my hand to my chest and took a breath.

—

You have reached the voicemail of Dr. Marvin Kendricks. I’m not here right now, because there is no ‘here’ and there is no ‘I,’ since this is simply a digital reverberation of my voice in an infinite temporal loop. Leave a message or not.

“Dr. Kendricks? Call me back, okay?” The gas station doors slid open, and Angela strode out, flicking her hair and turning as if the laconic glances of the old men smoking by the ice machine were flashbulbs. I hung up the phone.

“Here you go. Red Alert Gatorade. Fixes everything.”

I’d told her that I was feeling sick, and hoped that’s all it was. A fever. Too much stress. A rare variety of delayed-onset seasickness. I shook the Gatorade and suddenly thought of Kendricks’ warnings. I stared at the thin plastic filaments that joined the cap to the no-tamper ring.

“Mind if I have a sip?” Angela grabbed the bottle and opened it, taking a long chug. I looked around the gas station. Everything looked normal. I felt normal. There was no need to assume anything was terribly wrong. An old man passed in front of the car, scratching his paunch and turning toward us to flash his yellow teeth at Angela. He climbed into a pickup with mudflaps of busty reclining women, a sticker of Calvin peeing on a Ford insignia, and a pair of metal testes hanging from the trailer hitch. I tried to come up with a clever comment about trucks as loci of American machismo, some comment to restore normality, when one of the mudflap silhouettes curled upward, as if the woman were doing a sit up.

As her knees moved toward her breasts, the black shape melted into a profile of a small figure, her breasts now the brim of a hat, her legs folding over to become the kobold’s nose. The black silhouette of the kobold’s face then spread out and pixelated, resolving into a red and white checkerboard flag. This one I knew—any sailor would. It was the Uniform flag: you are running into danger. The flag rippled before it blinked to black and seeped, like batter in a pan, back into the shape of the busty woman.

I grabbed the door handle and pulled. The handle swung loosely on its hinge.

“Did you need something else from the store? The passenger door gets wonky, you can’t open it from the inside sometimes.”

“Let me out. I’ve got to get out of here.” I jerked the handle several times then

mashed the power window buttons. Angela grabbed my wrist and pulled me toward her.

“Hey, Julian. Calm down. What’s the matter?”

“Something’s really wrong with me. I need a doctor, or something. I think I’m hallucinating.”

Angela put her hands on my shoulders, turning me to face her. She leaned forward so our eyes were only inches apart. The heat of her presence and her smell—overripe and hot, like composted berries—made me woozy.

“Eyes look fine. No dilation.” She moved her hand down my arm, pinching my forearm hard and then looked down at my skin. “Normal refill and color.”

I felt the heat of her skin and the thin cool swaths of her silver rings as she took my wrist in her hand. She watched the dash clock and counted under her breath.

“Pulse 73. Healthy range. You’re fine, Julian. Don’t panic. Long car rides can have weird effects. Motion sickness, low blood sugar, tricks of the light.”

“You’re not a doctor.”

“True. But being around so many users and drunks made me an honorary paramedic, practically. I know when someone’s about to crash, and you’re not.” She was still holding my wrist, still locked on my eyes. “Can I just say something, Julian? Thank you for listening to my whole sob story about Eli. I’m really glad our ships crossed.” Angela leaned forward then scooted upward, pressing her lips to my forehead. Her t-shirt slipped open and I could see that her nipples, half obscured in shadow, were pale and pointed. Something about their shape, their pinkness, made them poignant to me. Innocent. Angela finally pulled away, squeezing my wrist.

“I think your heart is working fine.”

—

“He’s probably just taking a lunch break,” Angela said, rising up on her tiptoes so she could scan past the crowd and the few dilapidated trailered boats. She sipped from a tropical cocktail she’d purchased at the entrance.

The “boat show” was nothing like I imagined. It was more of an ad-hoc flea market in an abandoned mall parking lot, with some booths seeming to be official—all with the same sized black fold-out tables—and some completely makeshift, like the man sitting in a director’s chair with a single Rubbermaid container of jumbled hardware at his feet and a hand-painted sign that read “All Offers Considered.” Even the more formal booths were basically selling junk—dirty old chains, ripped sails, waterlogged old chart books rife with countries that no longer existed.

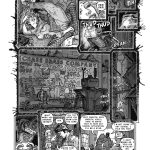

Eli’s booth was striking in comparison. A blue velvet cloth covered the whole table, serving as padding for a large, beautifully made display case. Beneath the glass, at the bottom of the case, stretched a sea of bunched blue satin, subdivided by a grid of small docks, coated white like the soft rind of Camembert cheese. There were dozens of miniscule ships in the display case, each neatly aligned in the scaled down marina slips, each held in place by hair-thin docklines hooked on silver cleats the size of earring backs.

Strangely, only a few of the ships were in bottles. A small sign noted that Eli would place the ship in the bottle upon purchase. The strain of performing this final act before an audience, I reasoned, was what caused the skew of each horizon. A wooden box, filled with impossibly small but recognizable tools (screwdrivers, wrenches, pliers, even a hammer the size of nail), lay open, next to the pile of pamphlets. Each tool sat in a velvet compartment, as much works of art as the ships.

Angela suddenly put her drink down and rushed forward. “Eli,” I heard her say, as she hurried toward a young man who walked with a slow gravity as if each step constituted a separate decision. He wore a loose pair of multi-stripe harem pants and a plain yellow t-shirt, the kind one would buy in bulk. Angela reached out as if to hug him, but he held up a hand and the two spoke for a few moments, occasionally glancing at me before walking over.

“Eli, this is Julian. He loves your boats. He’s a sailing scholar! And a good man.” She linked her arm with mine. I blushed, flattered and surprised.

“Julian,” Eli said, moving his mouth as if the word were a delicacy. He looked like Angela, but his face was wide and blurred, his small features submerged in baby fat and stubble. Dark hair hung past his ears in a tangled fringe like seventies-era drapes. He moved toward me and looked me in the eye, cocking his head and squinting as if my face were fine print.

“It’s nice to meet you, Eli.” I put out my hand, and Eli’s hand alighted on my wrist like a bird, his fingernails lightly perched.

“You’ve been at sea,” he murmured, lifting his hand and looking upwards as if he could see Tammy Sue cutting through the clouds.

“Yes, Eli, Julian had just come ashore when I met him. Enlightening and educating a fishing crew, in fact.” She squeezed my arm as she said this. Enlightening a fishing crew? That’s how she saw me? Warmth rippled through me.

“Eli, your ships are exceptionally rendered. I’m especially curious about the Otago.” I released myself from Angela’s grip to pull the bottle out from under my shirt. “If you don’t mind, could you share your sources?” I held it up to the sun for Eli, but when I did all I saw was the kobold, mashed into the bottle, blinking a large eye at me, the blue iris swirling like a funnel cloud. I dropped the bottle, feeling suddenly weightless and distant, an outside observer looking in.

Eli stared at my sternum where the bottle rested and raised his eyebrow. “Ah, my friend, the kobold. What a surprise.” He glanced at Angela. She was obviously pleased.

“You see? Julian gets along fine with the kobold. That’s how I knew.”

Fine? Kendricks was just a call away—911, too. But it was as if I was paralyzed and the phone in my pocket miles away.

“No, no. Let me tell him,” Angela was saying. She reached for the bottle, looked briefly into it, then let go. It hummed against my chest. “Julian, I have to explain something. You are perfectly fine. The kobold isn’t a hallucination. Eli has conjured—.”

Eli held up a palm to Angela’s face. “Summoned.”

“Summoned, yes. Eli, because he is such a caring soul”—she glared at Eli, droning the last bit like a teen employee reciting corporate patter—“has summoned for me a warding spirit.”

“Better.”

For the next several minutes, Angela spoke, with Eli breaking in. Men who fell in love with Angela saw the kobold, a sea troll … no, a protective spirit, a Klabauterman. Each one of them eventually left her, and a few of them lost their minds … absented themselves from Angela, thereby giving her a chance to grow. Freddie disappeared after having a square-rigger tattooed on his calf because the kobold told him to. J.J. broke into an electronics store to steal a white-noise machine to try to drown out the kobold’s voice. And Crater? The love of her life? The most corrupting of corrupting souls. Crater saw the kobold sitting in the sidecar of his Harley, right next to his black lab and drove off the road. … no, it was a yellow lab. For seven long years, the kobold had wreaked havoc on her life … if by wreaked you mean prevented.

“Prevented,” Angela pronounced the word slowly, just as Eli had. “Maybe so. Especially if it led me to Julian,” she said, squeezing my hand.

Eli rolled his eyes.

“Eli! You said yourself that a good man, a man who could see inside the ships, would not shrink from the kobold. Well, I’ve found that man.” Now Angela dug her nails into my palm. She began to give off a heat, and a sour smell wafted from her. “It’s over, isn’t it? Please, Eli. It’s time for the kobold to leave.”

“Your Julian looks unsettled,” Eli declared. “He’s just another imposter, and the kobold toys with him.”

The floor swayed and I took a deep breath, hoping it might help steady my feet. But all it did was draw Angela closer. The sweat on her hand mingled with mine. Warding spirit? It was insane talk. But they’d seen the kobold’s blinking eye just as clearly as I did. Was there such a thing as a shared hallucination?

Kendricks would know. I had to talk to him. He always told me to interpret Conrad’s sea stories as if only his narrators were real. His theory was that Conrad’s art mimicked the trickster mind of a sailor on night watch, conjuring whole worlds to avoid confronting the featureless darkness of a calm sea. “Becalming,” Kendricks had said, “is worse than any storm. In a storm, you’re preoccupied with keeping your ship afloat. In a calm, anything can take hold.” Could becalming happen on land? In the mind?

Angela turned to me, speaking in honey tones. “Julian, can Eli look into the bottle?”

I felt myself reeling back, my hand on the bottle. At that moment she and Eli seemed no more real than the kobold. And only the kobold, with his semaphore warnings, seemed on my side.

“I’d better go—”

Eli lifted his hand. “Wait. Don’t be afraid. Let us just see what the kobold has to say.”

Angela lifted the bottle over my head, and the motion was so proprietary—as if I were casually hers—that I was too surprised to react. For a moment it got snagged around my ear, and I felt her fingers press my earlobe to free it. Eli took the necklace from her, walked around the booth and came out with a jeweler’s loupe. He looked into the bottle, turning it under the sunlight and squinting.

“I can’t find him.” He muttered. “Not in the berth, not on deck, not in the galley, not in the bilge….” He rattled off nearly every part of a ship, then looked up. He turned the loupe around and peered through it at me, his face cocked if I could only be apprehended in the peripheral. “How strange.”

“Really?” Angela said, turning to me. “That’s wonderful.” She looked relieved, though I felt more unbalanced than before. I put my hand on Eli’s table to steady myself. Angela touched my shoulder; a tracer of sensation trailed down my back and petered out. I could feel the same undertow that I’d experienced beside the St. Marys River pulling at me again.

“I’ll get you some water, Julian. Don’t go anywhere.”

“I’m fine. I just need to step away and…” I managed, but she’d already disappeared somewhere among the other vendors’ tents. Eli was suddenly in front of me, holding the bottle at eye level. He raised his soft voice to an announcer’s volume, though somehow still in whisper.

“Did you notice? I hope you did. The ship you were wearing is the rarest version of the Otago. I’ve only made three.” He frowned. “Crater, that idiot, smashed the other two.”

I put out my hand to brush the bottle away, but I couldn’t resist one look.

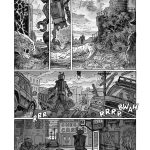

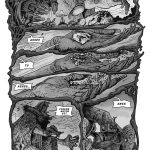

The Otago had been transformed. It now floated absolutely straight on the horizon, almost unnaturally balanced. And the topsides were gone, cut away so that the cabin, as depicted in the map, was fully exposed. As my eye followed the L-shaped cabin that fascinated Kendricks, it twisted and fragmented into a labyrinthine jumble of more L-shaped cabins, mirror images within mirror images. My eyes seemed to be capable of focusing on smaller and smaller objects as they moved into the ship, so that the indistinct blurs of details too small would blossom into clarity the more I looked. There were infinite sleeping bunks and infinite dinners of soda bread and infinite broken sextants the captain had laid out to fix, and as my eye continued to move deeper into the cabins, I noticed that each new one had a small detail out of place, a different colored blanket, an unlaced boot on the floor where in the last cabin it had been laced, and so on.

“It’s spectacular,” I murmured. I looked up and the light had shifted. Angela’s abandoned cup had sweated through to the tablecloth, and her cocktail umbrella had sunk into her melted drink. How long had I been looking? How long had she been gone?

“Wait until you see the very center,” Eli whispered.

I looked back into the Otago’s bottle, following the cabins from the beginning, half hoping I might see the sprite again. Just as the last cabin opened before me, and my eye seemed to brush the curtain from the sleeping quarters inside, I felt my phone buzz in my pocket. Kendricks—I was sure—but let it ring. There, in the bunk where the murderer from the “The Secret Sharer” had been secreted away, lay Angela’s sleeping body. She wore the same striped dressing gown that Conrad described. She opened her eyes, and I saw my own face, gasping in astonishment, reflected in the blue sheen.

“Can you see her? It’s the smallest, animatronic replica.” Eli breathed.

“Yes…”

“My masterpiece. I think it’s time to finally show her.”

The figure turned with a small mechanical ping. My eyes settled on the curve of her shoulder, which shifted as if from her breathing. I reached out to touch her but found myself pulled in again, inward and inward, until the fabric of the dressing gown filled my view. The threads expanded then loomed like I-beams; a single fiber widened into a constellation grayed out by too many stars. Feeling my knees weaken, I willed myself back up to the main deck, thinking perhaps the kobold might yet be hidden among the anchor rode. Nothing stirred.

I turned to look for Eli, but could not pull myself free of the ship. An orange sun trailing light through the clouds blotted out the sky. The horizon line crumbled and what I had interpreted as a sunset was now a mass of color, a circular pattern moving across my visual field. The bright wad pulled away with a squeak, revealing a blurred and massive hand and Eli’s head—a distant monument. I stood on the teak deck of the Otago and watched as Eli polished the sky from the outside with a chamois the size of a thunderhead. I leaned over the rail and my glasses fell to the glass sea below, skidding and spinning before going still.

“Angela?” I called. Her name rose up and pinged around the bottle, echoes begetting echoes, compounded by the bottle’s sudden motion. Eli’s fingers, like some kind of stretched-low and ominous moon, draped the sky. He nestled the bottle into a dark pouch, into the depthless velvet pile, into the miniature slip. The silence was beyond a hush; it shrunk every sound. The sunlight diminished to a tenuous thread. Faintly golden, it illuminated the fish scales I coughed up every time I laughed or screamed or called her name.