Become a Christian

There is no exception. When Grandma’s getting ready for church tomorrow, tug at her skirt hem and say Grandma, I want to come to church too. She’ll scowl. She’ll remind you that Big Reds said the same thing five years ago, but now he sleeps in every Sunday and had that seizure the other day from smoking weed. Stand your ground. Point out that you’re nothing like your brother, and that it’s her Christian duty to set you on the path of righteousness. She’ll smile. She’ll call you a mouthy little bitch.

Stick with it. Go to church every Sunday. Every Sunday. Starch your white shirt. Press neat creases into your wool slacks. Save any little money you have for the collection plate and cherish the pocket-sized New Testament she’d originally given to Big Reds. On the bus ride to town, ignore the other kids. Sit by your grandma and assume the stoicism of a proud martyr. This means no complaining about: the holes in the bus floor, the rents in the bus seats, the heat pressing in from all sides. Sweat will run into your eyes and pool beneath your butt. But Jesus endured much worse on the cross, so keep quiet.

Don’t Make Friends

Okay, this is a two-parter. So first off, don’t make friends with the kids at church. I know this is tempting; church is so damn boring (can you believe it? Jamaica in 1998, and part of Holy Trinity’s church service is still in Latin), and these kids, they’ll want you to catch butterflies with them at first, out back, in the churchyard, ’round where the tombstones are. It’s a trap. They’ll grow eventually (well, the girls you’ll witness — the boys will start to disappear around 13). They’ll grow somber, like those heavyset women in church with the lining of their slip always dipping below their skirt. They’ll start to wear blouses that button at the neck, and fasten their hair in no-nonsense plaits. They’ll start to invite you to summer retreats and choir practices and, when you politely decline, exhale gasps of frightened outrage that seem way too heavy for their flat chest. You’re not here for all that work. So just keep to yourself from the outset. Sit by your grandma and shake hands with the ladies and the old men as they walk by.

When your grandma dies (terrible loss, really), you can ditch that fancy church in Kingston and go to one in your own area. Don’t go to one in your direct neighborhood, though — go to one on the other side of the gully where the roads are less formal (snaking through bushes) and the houses have a delicious ad hoc quality to them — zinced and planked and set atop cinder blocks. Notice how the roof of this church is flat. Notice how the windows aren’t stained. Notice how the floor is dirty, how the walls are bare and how the pews aren’t pews but fold-up chairs. Notice how the women here jump and wail and mash their faces into foregone ecstasy. Notice how, no matter what church you go to, the preacher’s son is always tall and square-jawed and smiling at you in a way that makes you wonder if there’s anywhere Satan doesn’t have a house.

Speaking of your hometown, this brings us to part two of this section: don’t make friends with the other boys in your neighborhood. That’s asking for trouble. Eventually, they grow into teenagers and confront the futility of trying to make it anywhere. They never know their fathers, and they never make it past the tenth grade. They spend time under the lampposts, by the gully bank, against the old trailer, slapping dominoes, shooting dice, slipping their hands under their girlfriends’ skirts. They’ll want to pull you in on it too. Seal the bands of brotherhood. The Christian defense won’t work here. They’re too basic, too disaffected. My yute, you doh see di girl a check fi yuh? Why yaa act like a pussy?

Trust me. Way too risky. Best to stay inside at all times. Except when you have to go to school, of course. Your mother will send you to good schools in Kingston, far away from the locals. That’s good. After school, when you get off the town bus, head straight home. People will call to you. They’ll say Brown Boy or Scholar or Preacher. It will be out of deference. They’ll admire your discipline. Still, don’t call back to them. Nod politely or smile. Sometimes you can hold up a hand in acknowledgement. Carry around your bible for good measure too. They know you go to church, but it’s good to reinforce this every once in a while.

Keep up at your studies. Otherwise, you won’t have an excuse to stay indoors. Your mother will begin to think it unnatural that a boy is spending all his time in front of a television, atrophying his muscles, neutering his presence. Studying is an excellent pretext. It assures her you’re determined to make the best of her sacrifices. It buys you some good bonding time with her too. She’ll bring you milk sometimes, a whole glass. She’ll put her arms around you. She’ll say you’re nothing like your brother (Big Reds’ been disappearing for days at a time now) and squeeze a little harder. You’ll feel her lips on the top of your head. You’ll remember how soft they feel pressing against your skull. You’ll wonder when will be the last time she holds you like this.

Avoid All Types of Playing Fields

This might seem random, but it’s worth noting. Whether cricket or football or basketball, they’re all the same — trouble. This won’t be a problem where your schools are in Kingston; all the playing areas are walled off and/or privatized. In your hometown, though, they’re plentiful, cropping up in dubious makeshift forms in the most inconvenient places. Be vigilant. Keep abreast of the changes in landscape and avoid the main thoroughfares. Playing fields line them. I know it’s tempting to watch the boys at play, but you’ll thank me. What do you think will happen when a ball comes your way? Don’t think it won’t happen, ’cause it will. And those men, the ones you like to watch, will lean on their haunches and heave at the air, expecting you to throw it back. And, bless your heart, you’ll try, but your throw will go awry (your wrist — always a bit too theatrical). Or you’ll try to kick it back, concentrating with all your might on lining up the ball with the plate of your foot, but the ball sails wild. It goes clear over the light wires onto a rooftop or across the gully into the bushes — it will go everywhere but straight (Tee hee). The men will laugh. They’ll call you skettel, Shelly-Ann or Big Reds’ likkle sister. They’ll ask you what color panty you prefer. Even though it’s in good fun, it’ll hurt. You’ll develop an ironic fear of balls.

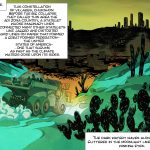

On your walks home, best to take the long way through the back roads. Through the flimsy dirt lanes webbing through the groves and wild grass that cordon the town. Buck up, though; you’ll make a friend. His name is Mr. Turner and he’s a sweet old man. Grey sideburns dip from his bald head and line his weirdly smooth face. But he has such nice brown eyes, bright balls of coppery brown eyes. He lives in one of those wobbly wood shacks that crop up by the back lanes like monstrous weeds.

He’ll call you over one day and offer you butterscotch. You’ll notice his house is not as ugly as the others; it’s a confident little wood square set atop slabs of concrete. And, look, he has a little garden to one side — bright bunches of cherry bougainvilleas dripping from a trellis of a fence. He’ll be sitting in a small wicker chair behind his front grill, the inside of his house dark behind him. He’ll tell you how you look like his grandson, who’s also about seven, and offer you butterscotch candy in a yellow-gold wrapper. You’ll start taking that lane regularly; you’ll tell him about your day at school in exchange for candy. When you get a little older, he’ll start giving you plantain tarts and little patties he baked himself; he’ll tell you about the daughter he hasn’t seen since his divorce thirty-odd years ago. She’s about forty now and has a son whom he’s only seen in a few pictures she’s sent. You look so much like his grandson, he’ll say; he’s probably growing a beard too. You’re curious; you didn’t even realize you were growing a beard. Come here, he’ll say, you’re growing some fine little hairs. He’ll reach his hand through the grill and you’ll move close. He’ll sweep the line of your jaw with a shaking finger. Are those really baby hairs? you wonder. Or is his hand that coarse?

When you go back the next day, he won’t have any patties for you. His spatula fell behind the stove and his hands are too big to reach back there. Do you think you could reach back there and get it for him? He’ll ask to see your hand. He won’t be smiling. Still you consent, and he’ll grab your wrist with a strength you didn’t know he had. Will you come and help me? he’ll say. His grip is hard, but his face is as still as dead water. You nod, holding his eyes with yours. He tightens his grip; his eyes are balls of thunder in the dark. Yes, you say again, and tick your mouth into smile. When he lets go to open the grill, run! Dart straight through the fever grass — tall, sticky fever grass slapping your wrists and scratching your neck. Cut into the burned-out clearing, then dash through the field of wild bush they call Deadman’s Fall. Jump the gully. Keep running. Keep running. Run until you reach the guinep tree at the top of the hill that overlooks the Fall. Take a breath. Drop your book bag and take a breath. Laugh, boy, laugh. Throw your teeth to the sky and laugh.

You’re such a tease, you’ll think to yourself. You’re such a motherfuckin’ tease.

Make Up a Girlfriend

Yes, that’s right. When you’re in high school, you’ll want to make up a girlfriend. Your classmates are from a different type of environment from yours. Their houses have carports, and they use summer as a verb. Thankfully, they’ll have some amount of decorum. They’ll not expect you to share sex stories, as they know you can quote Ephesians. Still, being Christian doesn’t exempt you from having a girlfriend. It’s convenient to make one up. So here goes: Her name is Rachel. She goes to your church in your hometown, and her favorite show is Step by Step. If they ask why you never bring her to one of the formals, just say that Kingston frightens her. They’ll believe you.

Be sure to have more interesting tidbits about Rachel so that she sounds like a human being. Keep cryptic notes on the inside cover of Wuthering Heights at home. Things like: R was born on May 6, 1988. R likes pink hibiscuses. R does not get the appeal of video games but has a brother who plays constantly so doesn’t mind it so much. In the unlikely event that your older brother (he’ll be back from jail around now) finds these notes on the inside cover of your book, tell him they are notes you’ve made on the novel’s protagonist, Romeo. He’ll believe you.

Near Final Note

All this work is wearying I know, but think, an American college is right around the corner. And I swear to you, there, you will have reached the promise land. There are, of course, practical matters of concern — Where do you do SATs in Jamaica? — Where are the American college applications? — What is your story? And how do you craft that into a compelling narrative? — Do foreigners qualify for need-based aid? What’s your mother’s salary like in US currency?

Daunting? No doubt. But now that the exit is so close you get to indulge in a bit of fantasy as a reward. Actually, it will be a good form of motivation. That’s right! You can finally start to imagine what type of boyfriend you’re going to have. Can you believe it!? B.O.Y.F.R.I.E.N.D.

Okay, so let’s see, he’s going to be your roommate — tall, broad shouldered, athletic build but not too hard. Blond hair, parted bangs and a baby face with a smile so earnest you’ll be convinced he still drinks milk with dinner. Hey! He’ll look just like James Van Der Beek. Yes! And he’ll wear flannel, and be from some outside-sounding place like Montana. He’d have played football in high school and, like you, had to work very hard to bury his difference. You’ll realize he likes it when you mistake American football terms. He doesn’t get to correct you often, so you give him this opportunity. “Oh my god, it’s end zone not field zone!” He’ll find this ignorance charming, and sometimes chuck you on the shoulder. He likes your accent too. You’ll sometimes catch him mouthing a word you’d just said, slightly in awe. And that is how it will happen, in the dark of your dorm room one night. You’ll both be sitting up in his bed against the wall, your head rested on his shoulder, his arms scooped around your back. It doesn’t matter how you got there, just know you’ll both be slightly drunk. He wants to know how you say ‘hello’ in Jamaican. Hello. And now he wants to know how to say ‘what’s up.’ Whaa gwaan. Whaa gwaan…he’ll contemplate it in a heavy whisper, gently rubbing the curve of your side. Your hand is now across the barrel of his chest, and you’ll marvel at the contained force of his heat. And even more, you’ll marvel at the exquisite realization that you’ve finally found your first friend.

The Return Home

So this is where I take my leave (for further tips on navigating the complex identity issues related to race and alienation within the American queer scene, please see Yes I Lacan: Dislodging the Pane of the White Gays”). But before I go, just a word about your return trip to Jamaica: don’t bother with the coming out thing. This trip won’t be about you. Plus, your mom will be in a weird space with Big Reds’ death and all. She’ll look different when you see her, inching instead of walking, and her eyes will have sunken in. There’s something unmoored about her — this wild hair and rumpled skin. Was your mother always this ugly?

There’ll be no words between you. She’ll squeeze your wrist and turn to the cab then stay silent on her side of the back seat. Her hair used to be sleek and jet black, and her nails were always polished in a ripened pink like the insides of a guava. But her hands look cracked and dead now. You’ll think to take one of hers into yours, but what kind of a gesture is that after 15 years? No, better to think about the flurry of e-mails Big Reds had been sending you, the ones that would be irritants before his disappearance and a torment after: Hey bro, how are you?; hey bro, do you think you could help me with something?; I promise I’ll pay you back; How’s teaching going?; Please, I wouldn’t ask if it wasn’t serious; Hope you’re well, bro; Let me know when we can talk. Consider that he probably begged your mom for help too. Ponder the possibility that she ignored them as well.

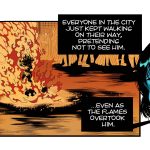

As the cab turns out of the airport and onto the Palisadoes, it will hit you like a brick of cold that it happened here, somewhere in the crevices of this wiry road snaking through the ocean. Or maybe they didn’t do it here. Maybe they chopped your brother up elsewhere, loaded the parts in the trunk of his car and left it at the lip of the airport in a whip of theatrical irony. Well, that’s assuming Big Reds was trying to get away from something. And that’s assuming “they” knew what irony is anyway. Oh dear, look at you, trying to construct a narrative.

Look out at the city, across the maw of dark water to the clump of small buildings huddled by the waterfront. This is Kingston. There’re more buildings, you’ll remark.

Yeah, the Chinese, she’ll say.

When you move to hold her hand, she’ll stare back at you from the plane of another world.

Mum, how did this happen?

How you expect me to answer that, son?

Simple. Just tell me what you know.

Her mouth too looks old, limp in a mesh of wrinkles.

I don’t know what. Maybe it’s the IMF.

The IMF killed Big Reds?

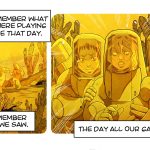

She’ll shake her head, raking the air with the teeth of her tin-gray hair, and you’ll remember, you’ll remember, she had grown ugly right in front of you. She’ll be saying something about the murder rate and the state of emergency, but you’re trying to remember your mother as a pretty woman, when she used to kiss you on the head and her hair would fan about you like a sheet. Why did she stop doing that? Maybe it’s because you stiffened when she started growing ugly. When was that? Maybe when grandma died. All her powders and creams had disappeared around then. Or maybe it was around high school; there was talk about her hairdresser money going to your monthly lab fees.

She’ll be talking about some riots. Do you remember the riots after the Free Zone got shut down? You won’t remember any riots. You’re trying to remember your mother’s hands, the way you witnessed them putrefy because of the clothes washing she started doing on the weekends. Whose clothes were they? It hadn’t concerned you to ask. But the money you remember going to Big Reds’ first bail because of…the riots?

Was Big Reds in the riots?

She’ll look at you, concerned.

No baby, Big Reds wasn’t in the riots. He’d already moved to MoBay, trying to find another job. Remember?

Why can’t I remember any of this? You’ll ask.

Maybe you were focused on the wrong things, she’ll say.