Category: Aquifer

Elegy for My Father

When he died last month at 91, my dad left boxes and boxes of black-and-white, sepia, and tinted photographs, along with a mahogany crucifix on which the Virgin Mary is suspended. Black hair, probably a horse’s, flows from the Virgin’s scalp and skirts her narrow waist; she has two tiny discs of grey-veined mica for eyes; and her feet are malformed, curving outward like jester shoes. I’d never seen this figurine in my life. I found it in Dad’s pocket a few hours after he died. The oddest thing, however, is that—whether it’s a fault of the woodworker, an act of vandalism, or a consequence of one of my father’s devious moods—the Virgin’s right breast is missing. The left side has an oval hump; but the right side is flat, smooth, and palely smudged as though rubbed vigorously with sandpaper. Along the back of the cross is carved: “To Amelia, from Dad.”

We shared many irreverent jokes; neither of us were orthodox Christians. But this figurine, I admit, makes me uneasy. Why is her breast sanded down? Can a single object inflect the narrative of an entire life?

Dad loved dolls, that I knew. He was the only man I’d ever met who kept an extensive collection of them—enough to fill an entire closet. As a child, I could never step foot in that uncanny sanctuary (or, to my mind, mausoleum) without chastisement; although at times, when he was out photographing the mountain landscapes and mountain people—the thing he loved to do above all others—I’d sneak in and caress their porcelain faces, turn their eyeballs to the left or right, or, when I was especially lonely, embrace them carefully without altering their positions.

There were big dolls and little dolls; conventional ones and quirky ones. I remember waiting for him in his Model T as early as nine years old while he hunted for dolls in drug stores and dusty furniture shops that made my allergies act up. The last doll he bought was in an antique store in Brevard, North Carolina; it was gigantic, dark-haired, with arms as pale and thick as split oak slats (I don’t know why this doll, in particular, finally satisfied his collector’s heart and completed his coven). He photographed them all, but of this Virgin Mary there are no extant photographs.

Dad was what you might call a shutterbug. He conceived of life as an album of images. His memories, for the most part, were tied to particular photographs he’d taken at one time or another. He entered Kodak contests and lost them. He wrote Kodak often complaining about their overrepresentation of northern urban photographers and the relative neglect of southern rural ones in contests; he wrote them about their new products; he wrote them about copyright law. I remember falling asleep to the ring-clack and furious metallic swings and snaps of the typewriter.

In the 1920s and ’30s, during the decline of tenant farming and in the heyday of folk photography, each town or hamlet in rural America had its resident photographer (Dad was born in 1889 and I in 1909). Men and women from Hemlock Cove, Olto, Judaculla, and Gallow Hollow frequented Dad’s studio and the Attic Window darkroom. They’d come with baskets of huckleberries, lovely foot-high April morels, and birch sap candy especially for me. They had names like Mossie Reynard, Earl Palmer, Gideon Laney, Imogene Bascom, Reinfried Romanes, and Max Straub. Like my dad, none of them made a splash in the photography world. At best they placed a few pictures in the Atlanta Journal or Audubon magazine. But Dad never kept friends long. He’d get into some bitter dispute with them about aesthetics or the superiority of a particular strain of vegetable. He had so many of these short-lived artist friends who shared and exchanged photographs with him that it’s impossible for me to know which of the tens of thousands of photographs he left behind are in fact his. The overwhelming majority are, certainly, but the outliers I can’t identify. My eye isn’t sharp enough and perhaps his style wasn’t distinct enough.

Throughout our lives, Dad and I would venture to the obscurest regions of our property, which was five square miles of oak, creek, and granite dome. He called our home in the cove Amelia’s World, because I spent all my time there gardening, walking, and writing while he was off taking pictures. We’d search for lonely abandoned chimneys from the nineteenth century—the relics of the crude cabins of Cherokee and frontiersmen, which often tilted dramatically on uneven ground. These one can find all over western North Carolina, hidden in rhododendron coves: creek rocks rising twelve feet high layered with clay chinking and reinforced with rope, hair, and hog’s blood; the splintered horizontal slats made of poplar. Over time, bees bored into the chinking’s hard pottery. Sometimes we’d light a fire in one of these crumbling hearths and smoke would pour out of the holes.

Dad’s death was a painful one. It feels almost irreverent to speak of it. The few distant cousins who visited struggled to keep their hands from their faces. He had bulging sores resembling purple tomatoes, some split open and oozing as if struck by the blight. His body was like a neglected garden at the onset of winter. I dabbed his sores with a cold cloth day and night during the final struggles. His last wish was for me to cover him with his dolls. His face glowed as he tossed and turned, coughing, spitting up fluid and blood; it jutted out from the top of the porcelain and cotton bodies so that it seemed he wore a grand, puffy Elizabethan dress with ivory lacework.

Dad had many sayings: “the best and worst things in life are errors of the stars”; “we’re just searching for a lucid interval”; “our knowledge is a journey from ruin to ruin.” These cryptic maxims I’ve found myself pondering in the days since his death. Over time, we came to share a similar philosophy. We believed travel outside Appalachia, for instance, would not edify the mind. Close observation of oneself and one’s immediate surroundings is the key to parting the curtains of mystery, however briefly; sense impressions decay into a precarious reality and the laws of nature can change at any moment. But we never held our breath awaiting those changes.

Some of his quirks I picked up. We both preferred corncob pipes with bowls cured with apple butter; it made the brightleaf tobacco from our garden taste sweeter and heavier than molasses (I’m smoking an old corncob right now at my writing desk; my hand shakes more than in the past and I pull the smoke with less vigor, but I experience the same relish as in my early adulthood). Neither Dad nor I owned a mirror. On the rare occasions we looked at our reflections, we did so in the convexities of tablespoons, and only then out of a sense of curiosity, never vanity or self-critique. We should move through life, Dad said, like a living soul in love that knows it’s loved in return, that doesn’t desire more or less as it stands on the bridge between self and other. That was his roundabout way of saying that we should accept our insignificant selves as they are.

I remember the winter it snowed and never let up, the flakes hissing and shifting on the branches, rocks, and roofs. In a fit of rage one day, due to some accident in the darkroom that ruined a batch of prints, Dad threw his ice-crusted walking stick against the wall—and it’s still stuck there. Somehow the tip wedged perfectly between two boards. We thought it quaint to leave it. In later years the walking stick reminded us of that long brutal winter and cut us with nostalgia, remembering the faerie cabins we built with pebbles and bark; the chunks of granite we heated in the stove and used to warm our feet; the icy shock of creek water in our throats; the night we glimpsed a freak offshoot of the northern lights weaving blue and violet nets around the moon; our midnight feasts on crystallized honey; and reading the Gospel of Thomas aloud until we drifted to sleep.

Living with Dad was not always easy. Rarely did we get on each other’s nerves, but there were times, especially towards the end, when he’d come in needy and sulking, desiring compliments. For sixty-plus years we’d discussed the people and places he photographed and the prints he left lying about the kitchen counter or that he had genuine questions about, which my untrained eye could help him clarify. When his body and spirit began to fray, however, he started leaving

photographs in places I’d find when I was alone: on my writing desk, bedspread, and rocking chair; in my tackle box, where I kept my rocks; and in my jewelry box, where I kept some beloved, much-read letters from an old flame. In the garden I once found a Polaroid caught in corn silk. It was a portrait of a woman I’d never met. She had sensuous lips that turned down at the ends and a bold beautiful forehead. Her eyes were closed; a horny crust, some kind of skin condition, populated her eyelids. The next day Dad asked me about it. Was it good or bad? Should he submit it to a magazine?

The first few times he did this I told him how moving the photographs were. I patted him on the back and flicked him affectionately on his balding pate. But as time passed, it angered me that he wanted me constantly to be his praiser and applauder, his confidant in art’s triumphs, failures, and transgressions. I wanted nothing more than the communion of easy laughter and the intimacy of long silence. That was how it had always been. It hurt to alter my attitude toward him, to play a role other than daughter. In the final two years his liberal spiritual convictions began to wear thin, and I suspected he was becoming secretly zealous in a manner he was embarrassed to admit to me, given our long history of unorthodoxy and light heresies. He’d hide himself away in his workshop reading a copy of the New Testament that he’d picked up at the Baptist church down the road. Once, when he lost his pipe, and we couldn’t find it anywhere in the cabin, I heard him mutter: “My God, why hast thou forsaken me?” I laughed. I thought it was a joke, but his expression was solemn. In spite of these things—which I’ve hesitated to commit to paper—he was my only friend and would’ve carried the cross or burned for me. An elegy, unlike a eulogy, should be honest in its longing for souls no longer in reach and should not shirk the hard truths of a complex life.

On the end table, there’s a browning, half-eaten peach with Dad’s bite mark still intact. I can’t throw it away. I think of how often he fretted, especially after he turned eighty, that all the peach trees in North Carolina were dying. He carefully documented their mutilations after the April freeze. He didn’t go exploring the mountains and rivers as far as Asheville anymore, but stayed near Amelia’s World, beekeeping, making muscadine wine, and worrying over our failing orchard. He often related dreams of worms, molds, and hard white blights like baby teeth infesting the fruit.

For some reason I can’t help but connect the missing flesh from this half-eaten peach—where Dad’s long, rabbit-like teeth scored as deep as the stone—with the Virgin Mary’s missing breast; and I can’t help but connect her missing breast to my motherless life. Of all people to have no photographs of, I have none of Mother (never “Mom”). Dad took hundreds of the goat man who visited the byways of Appalachia once a year in his junk-filled wagon pulled by goats; he has thousands—literally thousands—of pictures of purple martins feeding their young from perches in hollowed-out gourds hanging from poles. None, however, of Mother. Dad only started documenting the still, silent world after her death; in his photographs, the mysteries of loss were lulled into chemical innocence.

Mother passed away a few weeks after childbirth when I was two years old (my brother was stillborn). I was too small to remember her. Like clockwork, once a month (during the entire seventy-one years I lived with Dad, up until those final weeks), I’d walk into the house to find him drinking sassafras tea in the kitchen and crying, almost silently, his shoulders heaving. Few things made me so uncomfortable. It transformed me into his parent. I’d always pretend I didn’t see and pass quickly through the room. He never detained me but once. On that particular evening he spoke about Mother, how she had been feverish before she died. She didn’t rave exactly; she was lucid, just bathed in sweat and bright-eyed. She related certain visions: Christ in the desert, hovering, suspended in the air by magnets; a fiery cross erupting on the forehead of a goat; breaking a rock and seeing the face of Jesus inside it. The last vision she related, however, was more intimate.

She told of a day in Oberwolfach in southern Germany, the evening before she and Dad started their long journey to America. They’d decided not to go walking in the windy autumn hills above the village. She couldn’t remember why they’d stayed indoors; maybe they needed more time to pack. But in her vision they had, indeed, gone walking in the hills that day; they’d held hands; they’d kissed each other’s imperfections; they’d talked about what North Carolina might be like as they made for a gap in the trees, where the sun flooded the dim evergreen forest like a bomb’s light.

Dad, you were good to me. You were strong and gentle and careful as a mother. I’m a seventy-one-year-old woman now. When I smile the hundreds of wrinkles on my face hurt like paper cuts. It’s a testament to you that I have no fear of the darkness or the light. As I rotate this effigy of the Virgin Mary back and forth under candlelight, I want to glean more details, to see its mica eyes flash at me. I know that this object is some kind of provocation from you; a sign that I should rethink my life, my past and future, even at this late stage. It makes me wonder what other secrets you kept from me in that red-lit darkroom and in that closet of dolls, which did not replace me, exactly, but acted as a surrogate for something I can’t understand. What perversions, mean hates, and desires so naive and saccharine as to be almost scandalous did you hide from me? And where shall I go now? What shall I do? If I crack open the Virgin’s wooden skull, will there be a ball of mica inside it, a mineral brain not so different from my own? Will a thought rise from it like smoke?

The sky is the dark orange of persimmon beer as I finish this elegy. Orion, the hunter constellation, sparkles along the trees but Sirius has yet to appear above the hill. Perhaps I have twenty more years left, and I’ll die at 91, just like you. But with this inexplicable figurine in my hand, what tables shall I turn to honor, spite, or abandon you? Is the Virgin a key to open the kingdom within?

Jam Session in Poems

Cross Country, by Jeff Newberry and Justin Evans

WordTech Editions, 2019

Paperback, 110 pages, $19

In Cross Country, a collaborative book of epistolary poems published by WordTech Editions (2019), Jeff Newberry and Justin Evans pay homage to poet Richard Hugo. Hugo’s 31 Letters and 13 Dreams (1977) popularizes an epistolary tradition that originates in Ancient Rome and finds acclaim with Horace and Ovid. Hugo’s poems often address other poets such as Charles Simic, William Matthews, Denise Levertov, and William Stafford. Readers become voyeurs, dropped into intimate conversations between some of the most prominent poets of the twentieth century.

Hugo’s poems are often imagistic reports of a place, as he writes in “Letter to Wagoner from Port Townsend”: “Dear Dave: Rain five days and I love it.” These epistles transcend the reportage of place idiosyncrasies to reveal Hugo’s vulnerabilities and anxieties—both about himself as well as the world around him. In “Letter to Bell from Missoula,” Hugo writes: “Months since I left broke down and sobbing / in the parking lot, grateful for the depth / of your understanding […].” It is this balance of the specific details of a place with the personal thoughts of a brilliant writer and flawed human that has been so appealing to Hugo’s readers over many years.

In Hugo’s letter poems, we are only privy to one side of the conversation, however. We do not know how the addressees respond to Hugo—or if they respond at all. Hugo’s epistolary poems are decidedly one-sided; Newberry’s and Evans’ Cross Country, however, is a mutual conversation where both poets relay their deepest fears, desires, and hopes—to each other and to their lucky readers.

Evans sets the stage for Cross Country in one of the earliest poems in the book, “Letter to Newberry about Past Memories of Colorado”: “Dear Jeff: I think we’re all looking / for something, looking to run / to or from something.” Indeed, Cross Country feels like a search for a meaningful spiritual faith, for familial acceptance, and for a way to exist in a contemporary world that often seems mired in violence, sadness, and a persistent irrationality. This is a book that emerges from a contemporary scene that includes the mass shootings in Sandy Hook and Orlando and the 2016 presidential election, but it is also a book that asks looming personal and philosophical questions about love and loss, a book where we “want to see the mystery unfold, / complex as it might be” (Evans).

Evans and Newberry allow readers to see them at their most vulnerable—particularly when they broach the topics of their children, as well as of their own fathers. In a particularly tender sequence entitled “Letter to Evans: Like Waves Breaking,” Newberry describes his fears about his young daughter’s spina bifida, and ends the poem by writing: “I take each breath with her, willing my lungs / do the work for her. She sleeps and I sleep.” Newberry’s helplessness is profound, but it is in moments such as this one where a subsequent poem from Evans acknowledges Newberry’s anxiety and empathizes with him: “As a father myself, I / understand what you are saying, though / I cannot know the specifics of your fears” (Evans). The dialogue that Evans and Newberry create in Cross Country is deeply moving precisely because in it they engage fully in the difficulties of each other’s lives and offer each other comfort and solace.

If literature’s job is to teach us what it means to be human and how to empathize with one another, then Cross Country delivers those lessons in honest and accessible poems. Evans’ and Newberry’s narratives weave in and out of each other organically. It seems as though we are present at a blues jam session where the musicians have known each other for so long that they finish each other’s riffs. In fact, in the penultimate poem of the book, Newberry writes, “Justin, when you unseal this poem, remember / that it is made of voice the way that music is made / from the guitar player’s deft fingers.” The music in Cross Country will break your heart. Just like the greatest songs, though, these poems also sound the bells of hope and grit because, as Evans reminds us, “We must each / set the bar each morning as we greet the new day, / as each new day is certain to find us, willing or not.”

Trauma Bond in March: After the Miscarriage

for Chelsea

The tulips have flowered too early.

I cover the beds in white sheets

to keep them warm.

Frost pulled down from the stars

will soften

into a remembering

by morning. I am no mother

to the flowers or anyone.

It’s spring

and the world feels more delicate

than before.

Winter clipped. New wings lifting.

Doves adoring the sound

of their own song.

I have been told

some plants bloom once then die.

Flight is the answer,

though water can be an answer too.

Everybody (body) a vanishing act.

Seed without root.

And now the petals fall,

wishes to love

and love-me-not.

And now, the sound of distant laughter

enters my open window,

like ghosts. Softer now,

gentle weight of these small bones.

The Beheaded (or, A Sward for the Disembodied)

The French aristocrats persist in their delusions of grandeur, confirming they learned nothing from their cart rides to the guillotine. They revel in their precise necklines and pooh-pooh without decorum those like the Inca with ragged tears from a puma’s claw and the turbaned apostate with saw marks from a scimitar not properly sharpened. Some even grunt or humph on occasion as though still in touch with their upper-class gastronomic disorders. A few of the other heads may suffer now and then from phantom torso, but clearly these aristocrats are putting on airs of self-importance.

Roundabout a gross in all, these heads loiter in the grass like a gaggle of free-range bowling balls. The only criterion for membership is the complete separation of one’s neck from the body, intentional or no. The uneven ground ranges off in all directions into an unfathomable dark they have not the capacity to plumb. The grass itself is downy and kempt, not unpleasant to reside in, provided one is not vulnerable to oral, nasal, optical or aural intrusion. New arrivals drop from the murky haze that serves as sky and plop into available space. Thankfully, there is no pool-balling, but the way one lands is generally one’s position for the tenure of this after-existence. Thus, the fenstermaker, struck off during a freak installation accident, lies idly on his cheek, free to engage in idle conversation, while Nazi doctor Horst Fischer, facedown, can do little but mumble (to the relief of his adjacents). Rosalind Thorpe, the Co-Ed Butcher’s fifth victim, landed similarly but was industrious enough to tongue her way onto her ear. She beams with accomplishment when she hears the Nazi’s muttering, until memories of that which initiated her into this place sets her eyes quaking like jelly globs.

But before an arrival can have available space, a cranium needs to pop out of existence. They do so like bubbles, leaving behind neither trace nor debris. Neither arrivals nor departures go by any discernible logic. Jayne Mansfield arrived well after David Pearl, a seemingly beneficial swap at first, but her lack of bosom made Jayne quite the bore. She subsequently popped to make way for a Saudi extremist spouting pro-democratic slogans. Yet the ancient samurai remains, as well as the aforementioned Inca, who flares his septal bamboo when anyone makes eye contact for too long.

Their arrangement also seems indiscriminate. The aristocrats, for example, have but one trio in proximity, while the others reside singly among those they scoff. A cotton slave done in by overenthusiastic lynching glares at the aforementioned Herr Doktor. John the Baptist lies face-to-face with a Viking, the samurai alongside a poor kid who got truncated by the world’s tallest waterslide. Yet Medusa, her petrification skills as limp as her serpent tresses, is seemingly attended to by Henry VIII’s executed wives. The Greek is the only one who balances on the base of her neck, which in truth is the most level of them all, having been excised by deific steel, so she stands (metaphorically speaking) as though surveying the landscape, Anne B. and Catherine H. oriented well enough to watch over that which extends beyond their lady’s periphery. Some figure her snakes might not have been deceased when she first arrived and delivered her to her present position, but no one predates her arrival, so all hypotheses are the result of pure speculation.

The afterlife of decapitated heads is full of debate and skepticism. Belief is the number-one topic of conversation. What have they left but to question their surroundings?:

Who established this place? Does the choice of verb ‘establish’ load the question unfairly towards a God-based conclusion? The ordering of arrivals and departures, not following temporal logic, suggests some kind of selection is at play, but is that selection natural or super-thereof? Why doesn’t the grass grow, and why doesn’t it dry out since there’s never been a hint of rain or cloud ever from the caliginous expanse overhead? Could this place be the dream-invention of a single brain in the midst of its ninety seconds between separation and finality? Answers aren’t easy, even for those determined in their beliefs, pro- or anti-theist. If this were paradise, why subsist as heads alone? If punishment, what kind of Dantean contrapasso is at play? Discussions are curt and thankfully absent of palaver, for the wind of the bodiless is limited to their open-ended fragments of esophagus. Thus, they speak only in quick bursts, no more than two syllables at a time. A not atypical exchange:

“God.”

“Sure?”

“No doubt.”

“How?”

“Just look.”

The only exercise the beheaded are capable of anymore is to vacillate between despair and relief—relief that their existences didn’t just cut to black, despair that their continuation still contains no definite answers, their brains still boggled at the nature of things.

Though their distribution will vary according to the whimsy of arrivals and departures, overall they remain a hodgepodge of creeds and philosophies, from the standard repertoire to paganism to Wotan to rigid irreverence. The Viking considers a hall of heads the height of honor, while John the Baptist cries, “Repent! Repent!” Even John’s adherents, however, consider him unremittingly goody-goody.

A philosopher caught up in the Khmer Rouge revolution wonders if their situation is case and point of brains in a Cartesian vat, though even that conclusion necessitates further speculation on the placement of the evil daemon (or genius, depending on your translation). Joseph Haydn insists this existence a gift to promote the ultimate life of the mind, though he is considered something of an infidel, his decapitation done postmortem for phrenological purposes. The aristocrats spit and curse the name of Robespierre, but in their own way, being short of saliva and limited of wind. They wish him in their midst, for justice’s sake.

In the pale haze of sky, an unphased moon glows with persistence, making these crania shine like irradiated shrapnel in their lawn, or deep-sea pufferfish, aglow and uffing their jaws for life-giving water. Medusa and the former Mrs. Henry VIIIs look on without comment.

My First Time

in honor of International Women’s Day, March 8, 2020

The memory buzzes under

my skin like neon—in my young

twenties, before I understood

my daily risk of harassment

and humiliation, before I had

grievances, before I knew I was

entitled to grievances, I was

at the gynecologist, wrapped

in a johnny, lying down

on the examining table

for my first such exam,

knowing in the observing part

of my brain that a nurse

was supposed to be with me,

afraid of what the doctor

might find, and he entered

the room friendly, an older man,

asked me a few questions,

and then commanded, slide on

down here, Margot. I’m gonna

fill you full of cold steel.

No Brakes

In the spring of 1982, at the end of my senior year in high school, I was admitted to a mental hospital in Hartford, Connecticut, named the Institute of Living and was institutionalized there for two years. The Institute was founded in 1823, the first private mental hospital in the country. It was named the Hartford Retreat for the Insane and sat on thirty-acres on a hilltop above the Connecticut River. The first medical director was a brilliant young doctor, recently graduated from Yale, named Eli Todd. Whereas before, the mentally ill had been viewed as possessed, had been shackled, warehoused, or worse, Todd had a revolutionary vision for the humane treatment of the mentally ill: what he termed “moral treatment.” In Todd’s view, the mentally ill were citizens deserving of care and treatment and, ultimately, capable of rehabilitation and recovery. The key tenets of his treatment were “pleasant and peaceful surroundings, healthy diet, kindness, an established regimen, activities and entertainment, and appropriate medical attention.” “The great design of moral management,” Dr. Todd once said, “is to bring those faculties which yet remain sound to bear upon those which are diseased.”

I grew up in Hartford, often passing the Institute on Retreat Avenue in our wood-paneled station wagon. Driving by its imposing six-foot-high brick walls, my mother would comment, “There’s the country club.” And looking at those walls that surrounded the entire campus on all sides, I could imagine that it was a sort of English Tudor, turreted type of place. “There’s the country club,” I would echo.

I had broken down at school after I received an offer of admission from Yale University, scratching the inside of my arms with a razor blade as tears bled down my cheeks. I didn’t deserve Yale, I thought. I could never make it there. In fact, I could never make it anywhere. I had been a student at a small boarding school for girls in northern Connecticut. I had friends there, and teachers who encouraged me in an environment that felt like love itself. My school home was the opposite of the home in which I had grown up, in which I was despised as a disgrace, a lumbering, teeming, obese, and greasy monstrosity, a source of shame and disgust for my attractive parents. The love I had felt at school was all illusory, I realized that day in April, the thick envelope from Yale in my hands. I was not deserving of the kindness and care I had received during my years at the school. I could never make it at Yale. I could never make it anywhere. The fact that I had been admitted when my beautiful friends had not was an outrage, a cosmic wrong that could only be made right by taking a razor blade to my arm. When the cuts were discovered, the school psychiatrist recommended admission to the Institute. The recommendation came as a relief. A mental hospital would be a far more appropriate place for me, I secretly believed, than the hallowed halls of Yale.

And this mental hospital had a reputation that was equally hallowed, a cross between a country club and a vaguely dangerous sanitarium. I was taken on tour of the grounds a few days before my admission, the first time I had been inside the six-foot brick walls. It was a sunny, beautiful day in May and the campus was almost gleaming. The green sloping lawns, an aqua swimming pool (unused), and the largest flowering dogwood tree in Connecticut lent the impression of a hospital more spa-like than Bedlam.

I, of course, had read The Bell Jar, and I could easily imagine Sylvia Plath’s fashionable, intelligent and humane Dr. Nolan here, wearing “a white blouse and full skirt gathered at the waist with a wide leather belt, and stylish, crescent-shaped spectacles.” I had a brief consultation with a psychiatrist at the Institute’s Children’s Clinic. He wore a corduroy jacket with suede patches at the elbow. He puffed on his pipe as I sat in his cluttered office and tried to describe why I had cut my arm.

“I think it would be best for you to come to the Institute for the summer,” he told me, “so you can be all fixed up and strong for Yale in the fall.”

It seemed a reasonable, even hopeful plan. The prospect of Yale loomed like a leviathan in my mind; a place full of students as disciplined and serious as my father, frugal and ascetic and fiercely intelligent. I on the other hand was gluttonous and hedonistic, a disgrace—too loud, too voluptuous, too greedy, too fat, too emotional, too funny. I had thick eyebrows and fat lips and a tiny, ridiculous voice. I ate and ate and ate and ate. I would be much more appropriate in a place populated by the people of Robert Lowell’s poem about McLean Hospital, “Waking In the Blue.” I didn’t understand the poem then, not really, but it was so extraordinarily lush and generous and almost loving about all those Mayflower screwball patients like Bobby, “redolent and roly-poly as a sperm whale in his birthday suit.” I wanted (naively and stupidly) to be in Lowell’s place, where azure day broke, where I could feel safe, where that overwhelming pressure to hurt and punish myself could be lifted, maybe, just an inch, like in Plath’s The Bell Jar, and the fresh air could come rushing in.

What I didn’t know then was that the Institute, in its ambitious expansion, had become a far larger and more menacing institution, a hospital of last resort for patients who had failed or been expelled from other treatment facilities. It routinely performed a rudimentary form of electric shock therapy and bound patients in ice-cold sheets called wet packs for hours at a time when they acted up. There was an entire five-story “research” building constructed for the purpose of performing icepick lobotomies on patients from all over Connecticut, as such cruel and brutal operations were illegal in nearby Hartford Hospital. The advent, in the 1950s, of anti-psychotic drugs—like Thorazine—enabled the hospital to control unruly and disturbed patients with chemical restraint using doses of these powerful drugs that far exceeded the therapeutic range. Moreover, and most importantly, the insurance policies of the day, in the city known as the insurance capital of the world, often covered months and years of hospitalization, so an extended stay at the Institute was no longer the purview of the very wealthy.

By the early 1980s, when I was admitted, the hospital was taking full advantage of an adolescent population whose parents had good insurance. At the time I was admitted, the Institute had more than four hundred inpatients, nearly all of them hospitalized for long-term care (often called custodial institutionalization), and nearly always paid for by insurance policies. This was also the case with me. When I was admitted, I was covered under my father’s policy, which provided full coverage up to $1.5 million dollars—the equivalent of thirteen and a half years at the Institute. And I was stepping into an Institution whose financially savvy (or cynical) directors were more than ready to take advantage of an insurance policy that covered everything for a long-term stay and a family that wanted their troubled adolescent off their hands, and even out of their lives.

The Monday following my consultation, my parents and I drove through the black wrought iron gates for our admission appointment. An aide helped my father with my suitcase and then took it away. We sat across from each other on upholstered chairs in the mustard-colored lobby, my parents silent, holding hands. My mother was wearing a beige suit with gold buttons and sling-back spectator pumps. There was an air of excitement, almost giddiness about her, her hair glistening and her legs crossed prettily at the ankles. She had shopped carefully for her new outfit, spending Saturday at Lord & Taylor’s while my father and I watched old episodes of Hill Street Blues my mother had recorded on VHS tapes. My dad had been silent waiting for my mother to return, sitting next to me in front of the television, his pipe in his mouth, watching one tape episode until its end, and then replacing it with the next, in our old machine that ground and clicked.

My parents were instantly infatuated with my doctor, a tall, lovely Norwegian psychiatrist named Erna Mugnaini. She had blue eyes, wavy blond hair, and a daughter my age who was going to Smith. She spoke with a mesmerizing Nordic cadence that seemed intrinsically kind. My father dubbed her, “The Good Doctor.” She would speak to my parents first, she told us, while I got settled in the unit. Later that day she would come and talk to me.

I have the record Dr. Mugnaini wrote of her first meeting with my parents. It is telling that her first impression of me came from my parents, rather than from me or from any of my teachers. I had been in boarding school for four years and saw my parents only on breaks. I had not lived with my father, at all, for more than six years, not since I was twelve years old. She did not hear from any of my teachers, or my friends, or my house-parents, or any of the people I had been living with for the past four years. My parents, whom I seldom spoke to or saw, became instant authorities on my condition and adjunct therapists.

In the intake summary, Dr. Mugnaini writes: “Dolly’s emotional difficulties date back to childhood. According to both parents, she has always been a moody, demanding, oppositional and jealous child.” She describes my father: “Mr. Reynolds is an attractive, slim, healthy-looking man in his middle forties. He is friendly and polite but does not reveal many emotions and was rather factual in his account about the daughter.” About my mother, she writes, “Mrs. Reynolds is an attractive, slim, forty-year-old[note]Actually, on that day, she was forty-one. I don’t know whether this is a small typo by Dr. Mugnaini, or, more likely, a small vanity on the part of my mother.[/note] woman, looking younger than her age, well-dressed, pleasant and cooperative.” My younger sister, Kitty, was described by my parents as, “outgoing, friendly, easy to get along with, a bright girl but not particularly interested in schoolwork.” She goes on, “Kitty was born when Dolly was almost two years old. Mrs. Reynolds believes she ‘catered’ to Dolly to prevent her from feeling jealous, as both parents describe Dolly as moody and attention-seeking since early age.” Clearly there was only one problem in this family, soon to be behind locked doors.

Later, when my parents came to say goodbye to me on the unit, my mother told me excitedly that they had all come up with a name for all my problems: “no brakes.” I had never been able to stop myself; I had insatiable appetites for food and love and attention and jealousy and rage and despair and hopelessness. “No brakes,” they would repeat throughout my life, when they described the enormity of my appetites and emotions. But “no brakes” is what happened to the Institute, my doctors, and my parents as I rapidly descended into the world of an institutionalized patient and my father’s insurance company mailed the Institute reimbursement checks for my care, regularly, on the first of every month.

Dr. Mugnaini placed me on an intermediate unit, meaning the doors were locked but most patients were allowed on the hospital grounds in scheduled, supervised visits. The aide, Patty, who escorted me from the reception area, had a set of keys clanging from a chain she wore around her waist like a belt. Patty was tall and soft-spoken, knock-kneed in her white Levi corduroys, a kind and patient young woman who wore tinted glasses and treated us patients with compassion and gentleness. I could sense this on that first day, and I was not afraid, even as I saw that the entrance to my unit was a double door with a small pane of prison glass at eye level. Patty unlocked each door with a series of clicks, and then barked at Debby, a patient who was peering out as we were peering in. The name of my unit was “Todd,” for the great and humane Dr. Todd, the Institute’s founder.

The unit itself was quite dingy—walls covered with chipped mustard paint, mismatched, sagging couches, a brown carpet badly stained. It was hot and muggy, and all the windows were closed. In the center of the long hall was the nurses’ station, walled off from the patients by a double layer of thick Plexiglas, with a small opening at waist-level through which the staff passed medication at four scheduled intervals each day. Next to this Plexiglas window the cigarette lighter was mounted on the wall, a small burner with an on-button the patients could press and then light their cigarettes off the hot orange circle, a mental patient’s kiss. Patty, whom I would come to know over the next two years, was one of the most humane and accepting aides in the entire hospital. It was fitting I met her first, when I was still a person on the outside. Stepping through those Todd doors with her was like stepping slowly into the pool, step after step, as the freezing water moves up your body little by little, until you are submerged.

Nancy, another aide, showed me into my room across from the nurses’ station. Nancy was what I would have then called prissy, her hair permed into perfect waves around her face, her lips pursed in vague disapproval or disgust. She blinked constantly—a tic. She had me remove my clothes and stand naked while she emptied my suitcase and searched through every crevasse. She took my driver’s license and cash and returned my empty wallet. After snapping on two layers of latex gloves, she had me bend over so she could pry open the lips of my most private parts, to search inside.

After I had gotten dressed, she handed me a small plastic cup containing three pills, two small tablets and a bright red capsule. After I had swallowed the pills, she had me open my mouth again and probed my cheeks and under my tongue with a wooden tongue depressor. Satisfied, she left me alone.

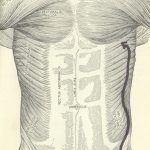

I found out later that the three pills were: 1) an antidepressant called Asendin (an older tri/tetracyclic no longer prescribed. Also, what a name!), 2) a catastrophically potent anti-psychotic in the same class as Thorazine called Trilafon, and 3) a drug called Symmetrel which is now used to treat Parkinsonian movement disorders. It was prescribed at the Institute because the older anti-psychotics like Trilafon have a terrible side effect: dyskinesia, which causes uncontrollable muscle movements, twitches and rigidity.

Most of the patients at the Institute looked like they had Parkinson’s. Those terrible drugs—Thorazine, Stelazine, Mellaril, Navane, Haldol, and Trilafon—were liberally and universally prescribed, in very high doses, and not only to patients with schizophrenia, but also to nearly all adolescents in the locked units, especially if they were unruly or acting out, which was also fairly universal. The discovery of these drugs in 1950s is considered a revolution in psychiatric care, allowing schizophrenic and other psychotic patients the possibility of an actual life. The way those drugs were prescribed at the Institute had the exact opposite effect.

Of course, I didn’t know any of this when Nancy handed me that first cup of pills, offered on a tray so that our hands would not touch. I had never heard of any of these medications. I had no idea that depressed people would be treated with medication instead of what I had imagined: kindness, insight, rest, and poetry workshops led by Robert Lowell and Anne Sexton, as had happened McLean’s and the other asylums I had read about.

I also didn’t know what my own initial diagnosis was, and didn’t learn of it until years later, when I read Dr. Mugnaini’s intake summary and discovered the catastrophic sentence: atypical mixed personality disorder with borderline, narcissistic, and histrionic traits. This very rococo description was, I’m sure, a result of Dr. Mugnaini’s conversation and collaboration with my parents and meant there was little hope for me in the world. My prognosis: “very guarded.”

Over the course of the my first few days and weeks in Todd, the medications were increased incrementally. I was lining up at the nurses’ station to swallow pills four times a day, until I was taking the maximum dose of the anti-psychotic drug Trilafon. With each swallowed dose, I lost progressively more control over my consciousness and my body. It was so sedating at first that I began to count the minutes to the next time I could sleep. I would get into bed one second after swallowing my 9:00 p.m. meds and fall into a black hole until Nancy woke me the next morning, rapping loudly on the wall above my head with a flashlight, her clipboard in hand.

I got to know some of the other patients. They were all women, and young, from age fourteen to about thirty. They introduced themselves with their diagnosis, the self and its affliction inseparable. Many of these women suffered terribly. There was Brenda, a lovely dark-haired woman a few years older than me, with violent manic-depression, cycling disastrously from psychotic mania to catatonic depression.

“My doctor can’t regulate my meds,” Brenda said to me, her hands shaking, a light sheen of perspiration across her forehead. Her doctor was Mavis Donnelly, the scion of one of the Institute’s previous luminaries, John Donnelly, a chief psychiatrist with a building erected in his name during the expansion in the 1950s and 1960s. Dr. Mavis Donnelly was young herself, a few years older than her patients, brutal and profane. One terrible day Brenda was out of control, wild with mania, and the nurses called Dr. Donnelly to the unit. When the doctor arrived, striding in in her tall black boots and wrap-around skirt, Brenda was jumping on and off the side tables next to the sagging couches in the dayroom, flapping her trembling arms unevenly like mismatched wings and laughing hysterically. When she saw her doctor, she cried out, “Dr. Donnelly! Dr. Donnelly! I can fly! I am flying right now! Look at me! Look at me!”

I was scared; scared for Brenda, scared she would hurt herself, scared for how wild her mind had become. I looked to Dr. Donnelly to help, but what she did instead was point her finger angrily at Brenda and scold her as loudly as she could. “Get down!” she yelled, her voice a guttural growl. “Get down RIGHT NOW!” I saw her snap her fingers at the nurses, and suddenly the aides were pushing us all into our rooms.

“What’s happening?” I asked my roommate.

“Brenda’s getting Gooned,” she answered.

And then I heard it, the thunder. When the staff hit the “Goon” alarm, five or six burly male aides came charging onto the unit and tackled the unruly (or offensive to staff) patient onto the ground. My roommate cracked open our door, and I watched as the Goon squad held a screaming Brenda face down on the unit’s filthy carpet and bound her wrists and ankles with leather straps. One of the Goons knelt with his fat knee in the small of Brenda’s back while she pleaded, “Please sir, please sir,” trying to catch her breath. Another Goon lay down a long black canvas bag with handle-straps next to her body. He pulled open a zipper that ran the entire length of the bag.

“What’s that?” I whispered.

“Body bag,” my roommate answered. “Like, for dead people. They’re taking her to Thompson.”

Thompson, the lowest of all the units, actually underground, in the basement, next to the steam room. Thompson contained the seclusion and restraint rooms, each bare except for a vinyl bed, like an exam table, in the center of the room, cemented to the floor. There were straps at each of the four corners, where patients were tied into “two-point” (wrists only) or “four-point” (wrists and ankles) restraints. The seclusion rooms were also where hysterical patients were “wet-packed,” a brutal and archaic form of “hydrotherapy,” abolished in nearly all modern hospitals[note]None of the psychiatrists I have seen in California, over more than twenty years, has ever even heard of wet packs, and had no idea that such practices were ever used on mental patients.[/note] but still raging away at the Institute. In wet packs, patients were bound, naked, between freezing sheets that had been soaked in ice water. The patients were left between these icy sheets and tied down for hours or even days. These descriptions now sound so baroque, unbelievable, even laughable, like some dark dungeon feature of a Gothic novel. But this barbarism was very much real and alive in Todd with a terrifyingly ill young woman and her angry doctor who could not tolerate seeming not in control of her patient. I watched as the Goons zipped a bound Brenda into the bag, lifted the bag with its handles, and carried it through the unit’s double doors, single file, like pallbearers. I also saw that Dr. Donnelly had been watching it all, her face frozen, impassive, her arms crossed tightly across her chest. It seemed incredible that ten minutes ago I had been happy to see her on the unit, thinking that she had come to help.

Where were the brakes then?

Brenda did not come back that night. I didn’t see her for another month, until I had been moved to Thompson myself. Brenda lay face down on her cot, immovable, nearly catatonic, as menstrual blood ran down her naked legs and soaked the sheet she was lying on. The Thompson aides screamed at her to stand up and clean herself up. Brenda was gone, unresponsive, unmoving, almost unconscious but still alive, her private blood sticky and red, a rebuke for all the world to see. But I was still in Todd when the Goons packed Brenda into the body bag. It was still early days for me at the Institute. I didn’t know any of what was yet to come as the unit doors in Todd slammed shut and the Goons disappeared. Dr. Donnelly walked into the Nurses station to write her report. That night I swallowed my meds and let the blackness fall.

—

The incident with Brenda had left me badly shaken, and there were other things that scared me as well. I asked Dr. Mugnaini about the side effects of my medication. My vision had become so blurry that I couldn’t seem to read. It felt like my eyeballs were quivering back and forth in their sockets. I had been a voracious reader, but now that I had lost the capacity to see the words I had lost a part of the world that had defined me. My teachers at boarding school had given me books to read outside of class, Chekhov and Ann Beattie and Toni Morrison and Eugene O’Neill, and then had talked to me about what I read as they drove me back to the dorm on a Saturday night after I had babysat for their children. My English teacher would even ask me what I was reading and what I would recommend. My father, when he came to visit me at the Institute on Sundays, would bring the Sunday New York Times for me to read, the Book Review thoughtfully pulled out and placed on top. It is hard to think of this now, my sense of my father and his gift of a life of the mind. I didn’t tell him I couldn’t read; I was ashamed. I carried the paper around the unit on Sunday nights, opening the pages and folding them back, holding them in front of my face and refolding them from time to time, a mechanical image of the person I had been just a few weeks before.

There were other things happening to me in what felt like from the inside out. My muscles felt rigid, my fingers splayed out and my hands held out in front of my waist, like a Tyrannosaurus rex. I shuffled and sweated and felt anxious all the time, like the area inside my body wall was quivering, being tickled unbearably by some internal torturer. These feelings were probably a result of my anxiety, Dr. Mugnaini told me, pen in hand, bending her blonde head to write the orders increasing my meds.

“You can have an extra Trilafon as a PRN,” she told me.

“A PRN?” I asked.

“A little extra medication you can take to help you when you feel upset,” she answered. I was already on 40 milligrams of Trilafon a day, but I had the capacity to take 8 additional milligrams, which would bring me to 48 milligrams, near the daily maximum and a very, very high dose of powerful elephantine drug. The Trilafon had knocked my brain with the force of a two-by-four. I did not have thoughts anymore, not in the way I had at school, and the thoughts I did have seemed to take forever to cross from one side of my brain to the other. It was becoming harder and harder to speak, both the act of moving my increasingly slack lips and the mental capacity to find something to say.

“You are quite ill,” Dr. Mugnaini told me. “You will need the support of the hospital for quite some time.”

And there were also other, more intimate shames that I was also keeping from Dr. Mugnaini. When I stood under the warm water in the shower at night, something was coming out of my breasts: a thick, milky yellowish fluid I thought was pus. It seeped and even squirted from my nipples, staining my towel, my nightgown and my bra with this unspeakable fluid.[note]Later I would find out that this was a bizarre side effect of the Trilafon called “galactorrhea.”[/note] And even worse, it was becoming harder and harder for me to urinate. It seemed to take longer and longer for my bladder to unclench. It was like I no longer knew how to send the signal for the muscle to relax. I had always, always been ashamed of my too chubby body, from the time I was in kindergarten and was not allowed to wear pants because people would see how fat my legs were. I had large breasts and thick lips and fat fingers; I believed that everything about me was grotesque and the filth on the inside of me was now seeping out as well. What kind of animal doesn’t know how to urinate? I was too ashamed to tell anyone what was happening.

By this point I was barely speaking at all. I had lost the capacity to read, I could barely think, I drooled when I opened my mouth, and unspeakable things were happening to my body from the inside out. I was eating almost nothing. It was the end of the world. I asked Dr. Mugnaini repeatedly if this could be from the medication. She looked at me thoughtfully and shook her head.

All brakes were gone.

—

All these years later, all these miles away, I think about what had happened to me as an eighteen-year-old, how I became an institutionalized, backward patient, sitting on the filthy floor of the basement unit Thompson, shaking and drooling and praying to God for each moment to pass, for two endless years, until the insurance company cancelled my policy and I was released, blinking, into the sun. I think about how the good Dr. Mugnaini kept increasing my Trilafon as I increasingly devolved, mistaking the side effects of the medication as symptoms of my ever-worsening pathology. I think about how this was all allowed to happen in an institution founded on the most humane and revolutionary treatment of the mentally ill, and how this institution lost the brakes on its greed, happily depositing the reimbursement checks from my father’s insurance policy as my life seeped slowly away. But most of all, I worry that I have lost the brakes on my own memories, that I can slip from being a mother and writer three thousand miles and three decades away from this experience, right back to the drooling and tortured mental patient I had become, and, in my most secret places, am still. And what I cannot seem to fight is the sense that my slim and attractive parents, mother in her spectator pumps, my father with a legal pad on his lap, the good doctor listening attentively, had been right all along. There are no brakes for that.

———————————

The Voices That Listen Behind Closed Doors

Up in the Main House & Other Stories by Nadeem Zaman

Unnamed Press, 2019

Paperback, 176 pages, $17

In many books that follow the struggles of the servant / lower class, the characters are so defined by their relations to those above them that their existences seem dependent upon and subservient to their masters and mistresses. Nadeem Zaman, however, circumvents this in his new and riveting short-story collection, Up in the Main House. By moving the master / upper class to the periphery, Zaman zooms in on the lives and humanity of those often oppressed in his birthplace of Dhaka, Bangladesh.

The result is a collection of seven connected stories in which the protagonists contend with personal conflicts amidst social, religious, and political disparity and distress. In the titular story, Kabir must decide whether to stop his wife—Anwara—from playing mistress while the home’s owners are away, yield to her newfound power, or join her. Meanwhile, “The Caretaker’s Dilemma” explores Abdul Hamid’s struggle to negotiate a suitable marriage for his daughter before he dies while negotiating manipulative dowry shenanigans. In contrast, “The Happy Widow” follows Rosie Moyeen, a woman blamed for her husband’s death, as she tries to reconcile memories of her marriage with her bitter neighbor’s stories of ex-husbands.

Kabir’s description of his mistress as a “high-strung hag” at the beginning of his story starts the collection with one of the many unapologetic voices that populate it. When his wife puts on such a persona, the class-based conflicts of identity and power siege Kabir in more intimate ways than any master or mistress could. Ramzan—the old nightguard that winks with “both eyes”—advises Kabir to join his wife but also threatens a failed thief with death and imprisonment. The resulting dynamic is simultaneously hilarious and unsettling. Zaman entertains readers while keeping them constantly aware of the characters’ potential fates. The deft handling of character, voice, and tone are a joy to read.

While “The Caretaker’s Dilemma” possesses the same elements of craft as “Up in the Main House,” it employs them to subtler effect while weaving in interiority, dagger-like dialogue, and social masks. Hamid is repulsed by his friend Sobhan’s greed but still agrees to negotiate a dowry since he desires to protect his daughter from the “shame” that is “always the burden of the girl’s side.” Zaman simultaneously humanizes Dhaka’s upper class and increases the story’s sense of dread when Harun Qureshi, Hamid’s master, tells him that he will pay for the dowry and warns him: “Whatever your friend asks you for, don’t say no.” Sobhan, on the other hand, reveals his true nature when he says, “In money matters even family comes second.” His smiles, underhanded insults, speeches about “honest … men,” and objectification of people make him a character the reader loves to hate. Even his servants are tainted, as can be seen in how they “help with the luggage” the first time Hamid arrives but are unwilling to do so when they think the deal is done. In all of this, Zaman shows that none are free of this society’s expectations—and consequences when they are not met.

“The Happy Widow” synthesizes parts of the other stories’ styles. Mrs. Zaheer, Rosie’s neighbor, possesses a blunt voice. She describes her ex-husbands as “a bastard of the highest order” and “a gambling, philandering louse,” respectively. In contrast, Rosie exhibits a complex interiority like Hamid’s. The story examines a female perspective not often addressed. Rosie admits that “the way [Mr. Moyeen] loved her scared her,” and the story explores her reconciling with what she did and thought about doing to test whether he was human, fallible. Because of her thoughts and actions, it is easy to dismiss Rosie as a near-sociopathic woman if one forgets the cultural grounding established in “The Caretaker’s Dilemma” and at the beginning of Rosie’s own tale. However, “The Happy Widow” is an amazingly subtle and complex tale about a woman coming to terms with her story in a culture that says she has none. Through small, precisely crafted actions—such as worrying if she had washed the dishes wrong and, in an act of rebellion, “[leaving a picture] slightly out of place”—Zaman allows Rosie and his readers to acknowledge and break away from enforced stories.

Though links to the Qureshi family are what primarily connect the stories, they are also united by how the protagonists’ actions are motivated by pride. In a moment of clarity, Kabir realizes,

His damn foolish pride; that had done it. Just like it had done it countless times over the years, … doing no more in the end than undoing his grit to push it away, leaving him as he was now, too far gone to turn back, give in.

The collection begs the reader to consider if the preservation of pride always leads to self-destruction and when pride is worth the damage it can cause.

Amidst this conflict and complexity, Zaman weaves fresh, compelling, figurative language. Songs are as “out of joint” as their singers. “Laughter rattle[s]” around and within characters “like marbles in a tin can.” Stories are repeated like the songs in a “precious record collection.” Life is askew in slight, beautifully unsettling ways.

The collection is not perfect: long stretches of dialogue dilute intense moments and pull the reader out of the stories’ world at times. Nor is it for everyone. The stories often do not end cleanly as many Western stories do and, therefore, ask the reader to imagine the future fallout or triumph. While I find Zaman’s choice to end his stories on moments of change wise, other readers might feel cheated of a final scene. As a whole, though, the book is an engaging collection of stories that entertain and discomfort as great stories do. When I finished, I found that I—not the characters—was the one with my ear against a closed door, hoping to hear another word.

I Loved the Dog So Much

I loved the dog so much. So, I decided that I needed to have it surgically implanted into my body. And I called the surgeon.

He was a short and astute doctor with a deep, trustworthy voice.

“You have too many internal organs,” he told me. “We’ll have to remove some in order to fit the dog in. No way the dog’ll fit otherwise.”

We agreed to remove all the unnecessary organs first. “You have two kidneys, two lungs, so one of each can go. I can remove one of your eyes just so you feel like you’re all in.”

I said take it all. The dog wasn’t too big anyhow. I imagined it would fit in my rib cage with a little room left for it to waggle its tail. “Make sure you leave room for it to waggle its tail,” I told the surgeon.

The surgeon did not share my optimism. “We’ll need to run valves through your abdomen for oxygen and sewage. The more I think about it, this is sort of like when they sent that dog to outer space,” he told me. “Except in this situation the dog will most definitely die instants after the surgery is complete.”

I asked him if he thought I should get the local university involved. At the time I thought this would be the kind of thing that would attract a young academic. Perhaps I was putting too much faith in the surgeon. The surgeon slept at my house that night. He said we would start in the morning.

He woke me up that night with a new plan. “We’ve been thinking about this all wrong,” he told me. “We have to remove all the organs, put the dog in and then figure out how to put the organs in, one by one like a puzzle. At that point we could even begin connecting the dog to your body so it could breathe with your lung and use your bladder.”

I thought about it for a moment in bed. “I worry we might suffocate the poor thing in the process of doing this. Plus, I believe you’re implying that through this surgery I might be able to hear the dog’s thoughts which was never my intention.”

“That’s impossible,” said the surgeon. “I’m only trying to fulfill your vision within the limits of my understanding of human anatomy.” The project was clearly wearing on him, though he seemed to be more saddened than upset. In the darkness he looked like a pale, bitter shadow.

“I’ll go get the dog,” I said. “The dog is the whole reason we’re doing this. Let me just put on my slippers.”

The surgeon sat on my bed. Thoughts flew through him the way that I’ve always imagined a computer thinking. A ticker tape of ideas fell from his mouth. “We could remove all your intestines except what’s absolutely essential. We could halve the size of your stomach, bladder, lung, and cut out all but a thumbnail-sized section of your liver. I’ve heard of people living with less. Imagine being able to live on an organ no bigger than the hard nail on your thumb,” said the surgeon.

I looked at my own finger. “The human body is a marvelous invention,” I told him.

The doctor came back to his senses after a glass of water. He played with the dog a while. “This is really a great dog,” he told me.

I said it was the whole reason for the project. I told him I was putting my body on the line.

The next morning, he cut me open in my living room. This is the only part I was unconscious for, so I only know what he told me.

Ghosts-Turned-Blue

Molly’s friend Ronaldo orders a second old fashioned, and she has to tamp down the voice in her head that itches to inform him (to lecture, she corrects herself) of what the ethanol (rotted plant waste is the phrase she really wants to use) is doing to his brain. Sobriety has turned her into her mother-in-law, Didi, who flinches every time Molly inadvertently uses “god” as an interjection. Didi assumes that the “god” of Molly’s interjections is Didi’s God, that by saying, “God, I’m exhausted,” Molly is likening Didi’s God to a “wow” or a “whoa” or a “yikes.” This perceived degradation offends Didi, yes, but the flinch is also Didi suppressing the urge to warn Molly that she’s booking herself a ticket on a high-speed train to hell. Molly has long found religious people intriguing in this respect—how earnestly they believe that they’re more enlightened than you and how this conviction convinces them it is their responsibility to instruct you on how to live. It’s infuriating behavior for sure, but she empathizes with their plight. To believe so certainly that the mother of your grandchildren is going to hell if she doesn’t change her ways, that’s a tough predicament.

Alcohol is now for Molly like God is for Didi, in the sense that Molly has spent so much time reading and thinking and talking about alcohol these past few weeks that she believes she knows it far better than Ronaldo and all these other restaurant patrons drinking their fancy cocktails and their blood-hued wine. Because Ronaldo is her good friend and she loves him, she feels an urge to warn him (to proselytize, Molly corrects).

It’s like one of those cartoons where the two characters are stranded on a lifeboat, starving, and one looks at his best friend, the chicken, and sees not his fluffy, feathery body but a golden-brown roast, his legs plump drumsticks. Super-imposed on Ronaldo’s warm brown eyes, Molly sees a cirrhotic liver, barnacled instead of smooth. Then that image disappears like a slide she’s clicked, replaced with—Oh god: not some crappy, too-sweet old fashioned, but Molly’s own former go-to drink: Maker’s Mark, with one cube of ice slowly melting. The trick was to pace herself, so she could finish the drink just as the ice finally dissolved. That was the perfect last sip, the signal that she could order another.

Molly shakes her head to dislodge the Maker’s, and Ronaldo’s face returns to normal, except he’s giving her a quizzical look. And Molly has to resist (the endless resistance! She understands why people use the expression “white-knuckling”; dinner at a restaurant is like gripping the side of a bouncy river raft) the urge to say, What the hell, dude? Why are you ordering a second cocktail in front of your good friend who has yet to make it past the one-month mark? Is that not a sign in and of itself of a drinking problem, of being in the thrall of alcohol, that you would make such a weak, selfish, and inconsiderate error in judgement? Does not such behavior warrant a lecture on ethanol and cirrhotic livers, since clearly Ronaldo needs saving from himself?

Then again, did she not tell him barely forty minutes ago that he shouldn’t censor his desire to drink? Did she not say confidently, “I’ve got this!”

These questions rattle in Molly’s head like cubes of ice in a glass.

As though he can read her mind, Ronaldo says, “You said you don’t even miss alcohol.” The look in his eyes makes Molly think of how she feels playing arcade games—braced the entire time for her avatar’s impending pixel-dismantling death.

He says, “Fuck, Molly.” He sticks up his hand to flag down their waitress.

The waitress quickly appears, and Ronaldo tries to cancel the drink, but Molly says, “No, don’t cancel it. He wants the drink.”

The waitress has a head of silvery white hair that is almost violet. Rather than make her look old or worn, her hair makes her vibrant and hip. She eyes Molly’s pink prickly-pear lemonade, and Molly suspects that the woman has read this situation clearly. This embarrasses her. Alcohol is such a pervasive and deeply ingrained part of the culture that giving it up is akin to giving up gas-guzzling transportation. Forgoing it makes her seem snooty and judgmental. Her abstaining inconveniences people. Molly’s friend Una commutes by bicycle only, which means no plans that include Una on the guest list can venture outside an approximately six-mile radius. And now Ronaldo feels like he can’t have a second drink.

Ronaldo says, “Please cancel it. Thank you.”

Molly says nothing, but she is already considering what she will write about this experience tonight in her online community of other people giving up alcohol without AA. The problem with AA, the group ethos goes, is that it is all about willpower, and so all about fighting your cravings. Instead Molly is learning to deconstruct her cravings so that eventually they aren’t cravings anymore. Supposedly this makes not drinking about gain rather than about loss. Supposedly it will make her more present and more joyful.

But here she is sitting across the table from her longtime friend, yet she’s thinking about the conversation she will later have about him with other people, strangers she doesn’t know anything about other than that they too have quit drinking. Well, that, and that they share her resistance to AA: a resistance which is not merely about AA glamorizing alcohol (as a permanent “craving” that needs to be resisted “one day at a time”), but also about its emphasis on submitting to a higher power. Molly isn’t “present,” she’s far away, imagining herself back in her bedroom, a space that’s felt cavernous ever since Connor moved out last year, and now, without her nightly, companionable Maker’s Mark, that much emptier.

Clearly Connor is not going to come to his senses, recognize how hard Molly is trying, how much she deserves to get him back. “Good for you,” he’d said when she told him she’d quit drinking. It was hard to explain what was so chilly, so measured about the phrase. On paper, it sounded supportive. But Connor’s delivery turned it into something else. It was that subtle way Connor emphasized “you.” He communicated that Molly’s quitting drinking was something that now benefitted her alone.

What do cravings become once they are no longer cravings? Molly has never posed the question to her group. She thinks of arcade games again. They were Connor’s thing. She’d always kind of hated them—even Pac-Man, her game of choice—because they made her so damn tense. Curious how those blocky ghosts’ pursuit of the little yellow corn kernel of a figure her hand was controlling could raise her heart rate so much. But she had always chosen to play rather than sit on the red sofa and wait for Connor to be done. She had chosen to play despite how much the experience frazzled her. Because there were brief moments of pleasure in playing Pac-Man, such as when she managed to maneuver her Pac-Man toward a piece of fruit, or better yet, toward a ghost-turned-blue. Then her Pac-Man could destroy the thing that had been taunting him, but only temporarily, until the ghosts resumed their normal coloring and consequently their normally lethal nature. Is that what a craving became when it was no longer a craving? A ghost-turned-blue that could turn on her at any moment? Because as much as she wanted to, she could not believe cravings could remain always and forever ghosts-turned-blue.

Or maybe the problem is she’s using the wrong metaphor? Maybe cravings dissolve into nothingness, like when Pac-Man dies three times and no jiggling of the joystick or the coin slot will bring him back to life unless you put in another quarter?

The problem is she can always get her hands on another quarter. So how do you make the cravings stop for good? You take a baseball bat to the machine and, after that, every other Pac-Man machine in existence?

And can the same alchemy be applied to Connor? Can she take a baseball bat to the memory of him? Make her longing for Connor disappear? Molly imagines asking this to a bunch of strangers who will reassure her (grandmotherly Pat134 and sarcastic but steadfast trickynick): You’ve got this, girl.

Daphne Kalotay on Female Friendships in Literature and Life

When Toni Morrison won the Nobel Prize in literature, Maya Angelou threw her a party. Eudora Welty tried to teach her friend and mentor, Katherine Anne Porter, how to drive. George Eliot and Harriet Beecher Stowe; Jane Austen and Anne Sharp… Probably I shouldn’t be so surprised that these female friendships are not as well known or well documented as those of literary men. As Margaret Atwood writes in her foreword to A Secret Sisterhood, “In accounts of the lives of male writers, peer-to-peer friendships, not unmixed with rivalry, often loom large—Byron and Shelley, Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins, Hemingway and Fitzgerald. But female literary friendships have been overlooked.” So, when I read Daphne Kalotay’s Blue Hours, which tells the story of a close relationship between two women, I felt compelled to ask her if she’d be willing to talk to me, not just about her book and writing life, but about female friendship.

In addition to being a talented writer, Daphne is one of my oldest and closest friends. We’ve known each other since we were nine years old, when the neighbor whose yard stood between hers and mine in suburban New Jersey cut back his hedges so that we could commute back and forth without getting scratched. We walked home from grade school together and, when we were older, sometimes walked aimlessly, flipping a coin to determine which way we’d turn. In high school, Daphne and I split the cost of a The International Directory of Little Magazines and Small Presses, and I distinctly remember hearing back from one of the journals that I should not send my handwritten drafts.

Since then, Daphne has published four books:

- Calamity and Other Stories,which was short listed for the 2005 Story Prize;

- Russian Winter,which won the 2011 Writers’ League of Texas Fiction Prize and has been published in over twenty foreign editions;

- Sight Reading, winner of the 2014 New England Society Book Award and a Boston Globe bestseller;

- and Blue Hours, out in the summer of 2019 from Triquarterly.

She’s received fellowships from the Christopher Isherwood Foundation, the Bogliasco Foundation, MacDowell, and Yaddo. After graduating from Vassar College, Daphne attended Boston University’s Creative Writing Program, and then went on to complete a PhD in Modern & Contemporary Literature, also at Boston University. Her doctoral dissertation was on the works of Mavis Gallant (and her interviews with Mavis Gallant can be read in The Paris Review‘s Writers-At-Work series.) She is currently teaching at Princeton University’s Program in Creative Writing.

Kirsten Menger-Anderson for TFR:

Do you remember any of the notes you got back from those early high school submissions? Did you get any encouraging ones? Did you publish anything back then?

Daphne Kalotay:

I remember thinking that I had to grow up to be a writer. In fact, I have a distinct memory of telling a wonderful babysitter of mine, when I was quite young, that I wanted to write a book about the street another friend of mine lived on, about all the adventures of the kids who lived on that street. And the babysitter asked why I wasn’t writing the book now, and I said I had to grow up, and she told me not to wait—but I was very suspicious of that; I knew I had a lot to learn. I recall that around the time you and I bought The International Directory of Little Magazines and Small Presses, a poem of mine won some New Jersey student contest and was published in some sort of broadsheet. But I wasn’t even in the highest level English class, if I’m remembering correctly. And yet I have a memory of somehow being allowed to join your English class, which was a grade ahead of mine, on a class trip. I think this shows the teachers were trying to help me!

Menger-Anderson for TFR:

I love that Mim, the protagonist of Blue Hours, is an author and that I can read about her first submission, too: her decision to submit to Harper’s, where she knows no one, instead of The Atlantic, where she’d interned: “Perhaps it was fear of being rejected by my former colleagues. But there was something else, too. I wanted objective, completely impartial, affirmation of my brilliance. I am not ashamed to admit this.” I loved this line. Many of the details you capture—from the party where everyone is an aspiring writer, to Mim’s hesitation to identify herself as a writer, to how it felt to check the mailbox for the submission response—the thrill of a personal note, the dread of a form—really resonate.

Reflecting on her early success, Mim notes, “I hadn’t yet found my voice; I simply wrote down those other voices that would not let me sleep.” It’s interesting to hear Mim reflect on her own early work, and I was hoping you could talk a little about your own work and voice over time.

What was your first publication? And do you feel like your early work reflects your voice now?

Kalotay:

Interestingly, my first publication wasn’t my own voice; it was translations of three poems by the Hungarian poet Attila József, published in the Partisan Review. This makes sense to me, that this would be my first work good enough to be seen in print. My first original work was published very soon after that, a story called “Alabaster Doesn’t Count” that came out in a broadsheet called Bellowing Ark. These little magazines are so important, precisely because they are so often the ones that give us these first chances, our first publications. They’re that first pat on the back that says, You’re a writer!

Menger-Anderson for TFR:

Like Mim, who continues to write and publish, you are, decades after our high school submissions, a successful writer. Is it what you imagined when we were kids?

Kalotay:

You know, I’m not sure I even had a vision of what a “successful writer” looked like or what that life would be, just that I wanted to write something people would want to read. The funny part is that I remember as a kid often playing at being a teacher, and teaching creative writing is also how I make my living, so that part of the vision definitely came true.

Menger-Anderson for TFR:

Blue Hours is your fourth book. Do you feel like you’re now an expert when it comes to bringing a story into the world, or is each book/release different? Can you talk a bit about what you love about the process and what is difficult? And how friends can help?

Kalotay: