» Nonfiction

The Art of Murder

Juliana Gray

It’s gently raining in Savannah, a scrim of yellow pollen floating on puddles in the historic downtown, where everyone I meet is talking about the trial. No one needs to specify what trial; only an hour away in Walterboro, South Carolina, Alex Murdaugh has just been convicted of the 2021 murders of his wife Maggie and son Paul. Murdaugh claimed to have discovered their bodies, dead from multiple gunshots, after coming home from a visit to his ailing mother. However, during the trial, the prosecution obliterated his alibi by playing a cell phone video, taken by Murdaugh’s son just minutes before his death, in which his father’s voice was clearly audible. The story made national news, but here, it must have felt local.

I’m here to teach a poetry workshop on a nearby barrier island, but before I catch my boat, there’s a museum I want to see. I walk past gift shops selling replicas of the bird girl statue featured on the cover of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, past a group of college students gleefully discussing Murdaugh’s two life sentences. I pause near a teenage couple on a bench. The girl is describing the very museum I’m about to visit to the disinterested boy; her tone is wheedling, like a child begging for ice cream. “They have, like, bodies and horror movie shit,” she says, “and paintings and pictures and letters and stuff from serial killers. But it’s, like, real.”

◊

When investigators and psychologists analyze serial murderers, one of the traits they often identify is narcissism. According to a study published by the FBI after a 2005 Serial Murder Symposium, “certain traits common to some serial murderers includ[e] sensation seeking, a lack of remorse or guilt, impulsivity, the need for control, and predatory behavior. These traits and behaviors are consistent with the psychopathic personality disorder.” Psychopathic personalities may demonstrate “glibness, superficial charm, a grandiose sense of self-worth, pathological lying, and the manipulation of others.”

In other words, a serial killer is often an attention-seeking asshole who believes he’s the smartest person in the room. Think of Jack the Ripper sending taunting letters to Victorian London newspapers, or of Ted Bundy’s grandstanding at his 1979 trial, one of the first to be nationally televised. Think of Alex Murdaugh’s insistence on testifying in his own defense in March 2023. Flushed and agitated, Murdaugh said he had lied about not being present at the dog kennels where the murders took place because his prescription drug addiction had made him paranoid. He repeatedly used the sentimental pet names “Mags” and “Paul Paul” when referring to his wife and son, insisting he did not kill them. The jury didn’t buy it; in fact, they seemed to find him even more repellent after his testimony. One legal analyst said, “I think he thought he could outsmart the jurors.”

The FBI’s serial murder study firmly debunks the myth that these killers are charismatic masterminds like Hannibal Lecter. The report says, “the media has created a number of fictional serial killer ‘geniuses’, [sic] who outsmart law enforcement at every turn. Like other populations, however, serial killers range in intelligence from borderline to above average levels.” Ted Bundy transferred colleges, changed majors, and even dropped out altogether before earning his BA in psychology seven years after graduating high school; his LSAT scores were below average, and though he was admitted to law school, he never completed that degree. Jeffrey Dahmer flunked out of The Ohio State University. John Wayne Gacy never finished high school.

Yet one particular quirk–a trait, a tendency, perhaps a talent–runs through the histories of many serial killers. Some of them, either while committing their crimes or during their incarcerations, also create art. Some write poetry or stories, but more often they draw or paint. And their art is on display in Savannah, Georgia.

◊

The Graveface Museum is located in a former cotton warehouse on Factors Walk, behind the touristy strip on River Street. An offshoot of Graveface Records & Curiosities, located a few miles away on the other side of Forsyth Park, the museum opened in February 2020 and was forced to close its doors just three weeks later. However, it survived the pandemic thanks to TikTok and other social media. True crime enthusiasts and fans of the macabre from across the country have journeyed to Savannah specifically to see the bizarre and often gruesome items the museum’s owner, Ryan Graveface, has collected over several decades.

I shake the rain off my umbrella and enter past a headless plastic skeleton hanging on the door. A sign around its neck reads, “I ASSURE YOU, WE’RE OPEN.” Inside, the air is musty; I have an urge to slip on the KN95 mask I carry in my purse. The gift shop shelves are crowded with possum tails, taxidermied squirrels, T-shirts, records, stickers, and enamel pins, many of them serial killer-themed. The vibe is both self-serious and campy. I buy a twenty-dollar ticket, and after a few minutes a teenage tour guide invites me and the few others who are waiting to “enter through the Mouth of Satan,” a gigantic papier-mâché devil’s face constructed around the doorway. I snicker, but the guide maintains his deadpan as we follow him through the curtain.

A shrunken head. A grimacing “Fiji mermaid,” a taxidermied monkey’s head and torso attached to a fish’s tail. Two-headed animals and other circus “freaks.” Framed letters from “Son of Sam” serial killer David Berkowitz. The windowless walls are covered with photos, postcards, and other documents, some framed or laminated, most simply taped to the walls and slightly crooked. I pass through most of these exhibits quickly, taking care not to touch anything. Past the incongruous pinball room, where a few people punch idly at the vintage machines, is a closed door with a sign proclaiming the Ed Gein Experience, but I decide to save that for later. Upstairs is where I want and dread to go. Upstairs are the true crime rooms.

◊

Ted Bundy wanted to die. According to an article in The Washington Post, “In December 1977, when Bundy was in a Colorado jail awaiting trial for the murder of a nurse, he asked a lawyer which state would most likely execute a killer. Florida, came the reply.” Days later, Bundy escaped from his cell and headed for the Sunshine State. He had already been convicted of kidnapping in Utah and was facing murder charges in several states. His mask had slipped, the monster underneath was exposed, and he had nothing left to lose. A week after he arrived in Tallahassee, he bludgeoned his way through a Florida State University sorority house, killing two women, Margaret Bowman and Lisa Levy, and horribly injuring three others. During his flight from the scene, he broke into an apartment a few blocks away and severely beat another young woman, who survived. Three weeks later, in Lake City, he murdered twelve-year-old Kimberly Leach.

These were not the stealthy abductions and murders Bundy had committed in the Pacific Northwest, but frenzied slayings guaranteed to end not only in Bundy’s arrest and conviction, but in his sentence to the electric chair. According to this version of his story–and there is a lot of lore about this charismatic killer–Bundy knew he was going to prison and chose certain execution over the possibility of life without parole.

Why? Well, in addition to being generally unpleasant and dangerous, prison is boring. It’s designed to be, as its inmates have been deemed unfit for society and sentenced to atone for their crimes. Yet as the focus of imprisonment shifted from punishment to rehabilitation in the 1960s and social justice advocates turned their attention toward the incarcerated, more educational and art therapy programs were introduced. Some programs offer vocational training in fields like woodworking or jewelry making; others provide outlets for creative expression such as painting, sculpture, and poetry.

On Florida State Prison’s death row, Bundy did not have access to art classes. There’s no indication that he had any interest in paints, pencils, or poems. But many men like him did.

◊

The John Wayne Gacy art gallery is an assault of color. Yellow walls groan with canvases, mostly oils, in bright primary colors. Gacy’s most frequent subject was, unsurprisingly, himself, or at least a version of himself. While living in Chicago in the 1970s, Gacy managed a contracting company; he also sometimes donned a clown costume and greasepaint to perform as Pogo the Clown at charity events, political fundraisers, children’s parties, and hospitals. Meanwhile, he murdered over thirty men and boys, concealing many of their bodies in a crawlspace under his house.

At the Graveface Museum, portrait after portrait of Gacy-as-Pogo looms from the walls. Swipes of garish blue outline the clown’s eyes; a lurid red crescent like a slice of watermelon embellishes his mouth. Small details in the background or the pompoms on his jaunty hat vary, but the pose repeats in frame after frame: in one hand, Pogo holds a bunch of balloons. His other hand is raised, the fingers slightly curled, somewhere between a wave and a benediction.

The Pogo self-portraits are a Gacy cliché, but I’m surprised at some of his other subjects: a red rose, several skulls, songbirds, a portrait of Charles Manson, a portrait of Elvis Presley. Between his 1978 arrest and his 1994 execution, Gacy churned out–and sold–thousands of paintings. People would commission portraits of themselves or loved ones, mailing photographs to the killer; Gacy charged around a hundred dollars per canvas.

Another frequent subject is the Seven Dwarves from Disney’s Snow White. Gacy painted them in different landscapes, marching to or from the mines, skating on a frozen lake, gathered around a bonfire. A museum employee tells me that Gacy painted dozens of dwarf scenes, but never Snow White herself. He was fixated, it seems, on the innocent-seeming little men, going about their daily business, all the while concealing a precious secret inside their cottage.

The museum website states that they own “everything that was in [Gacy’s] cell at the time of his execution, all of his company documents, travel records, receipts, 237 paintings, 1200+ letters, over 60 hrs of unheard audio tapes . . . and much more.” Only a fraction of these artifacts is on display, but Gacy dominates the true crime rooms, covering several walls.

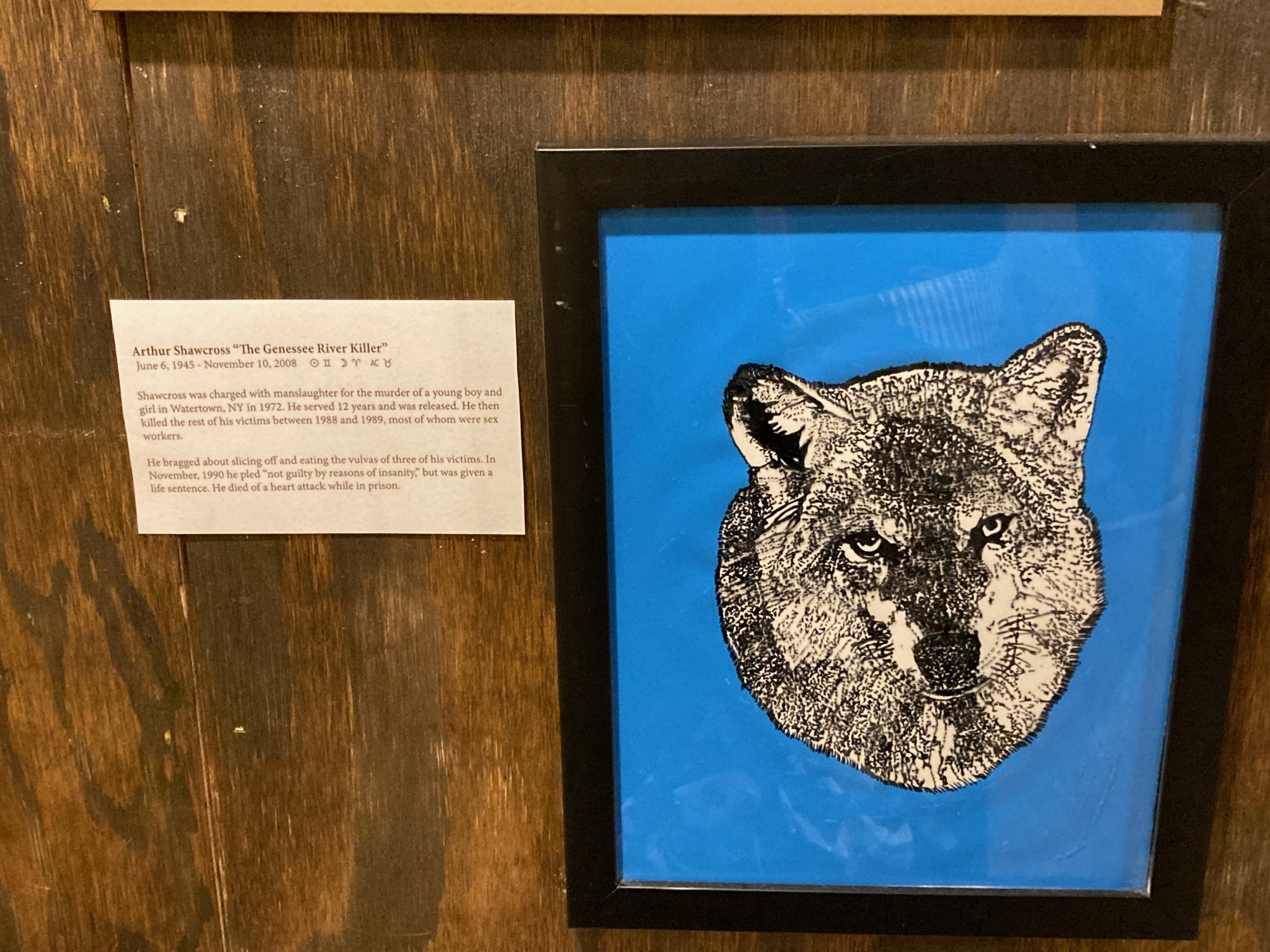

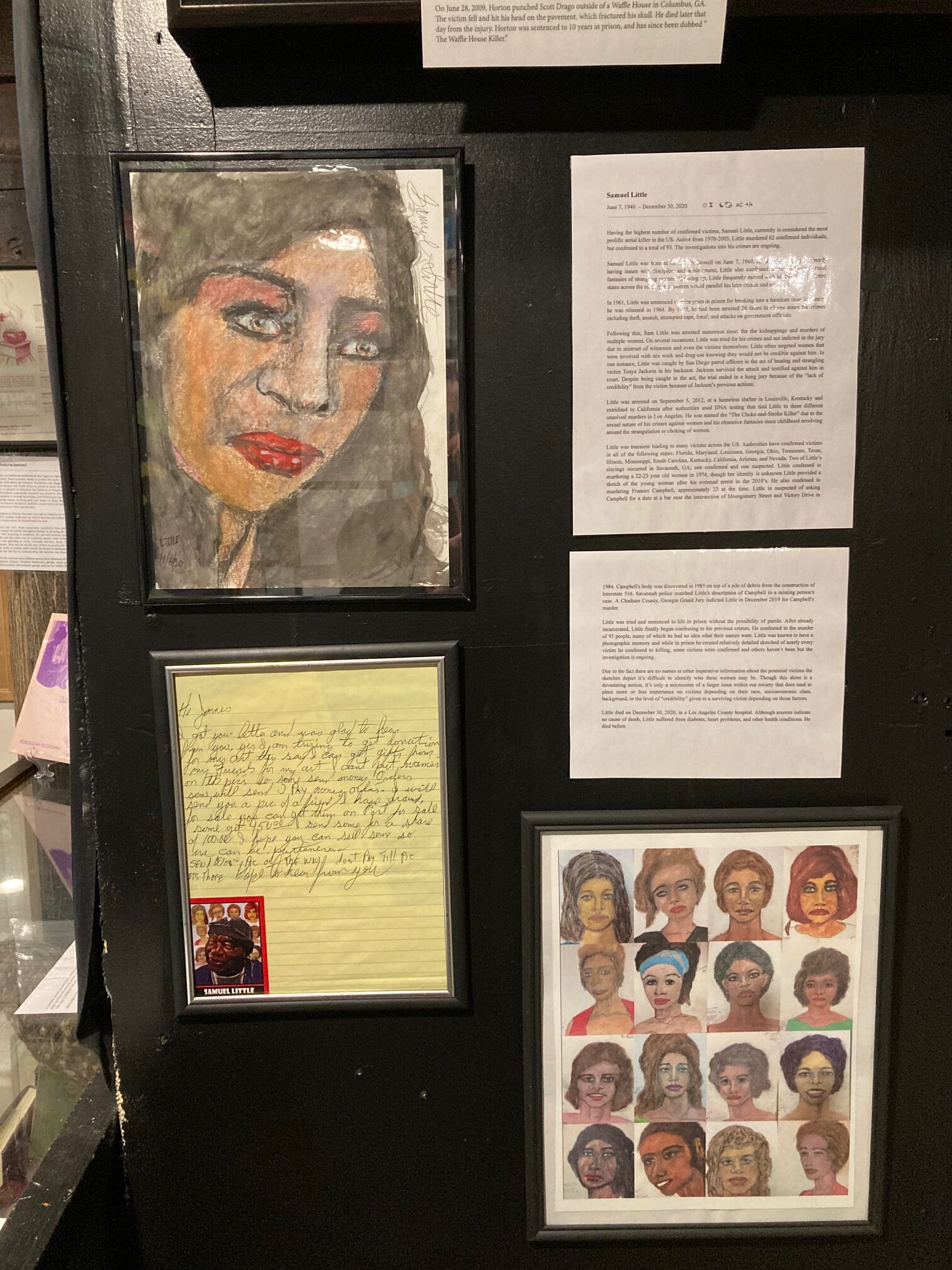

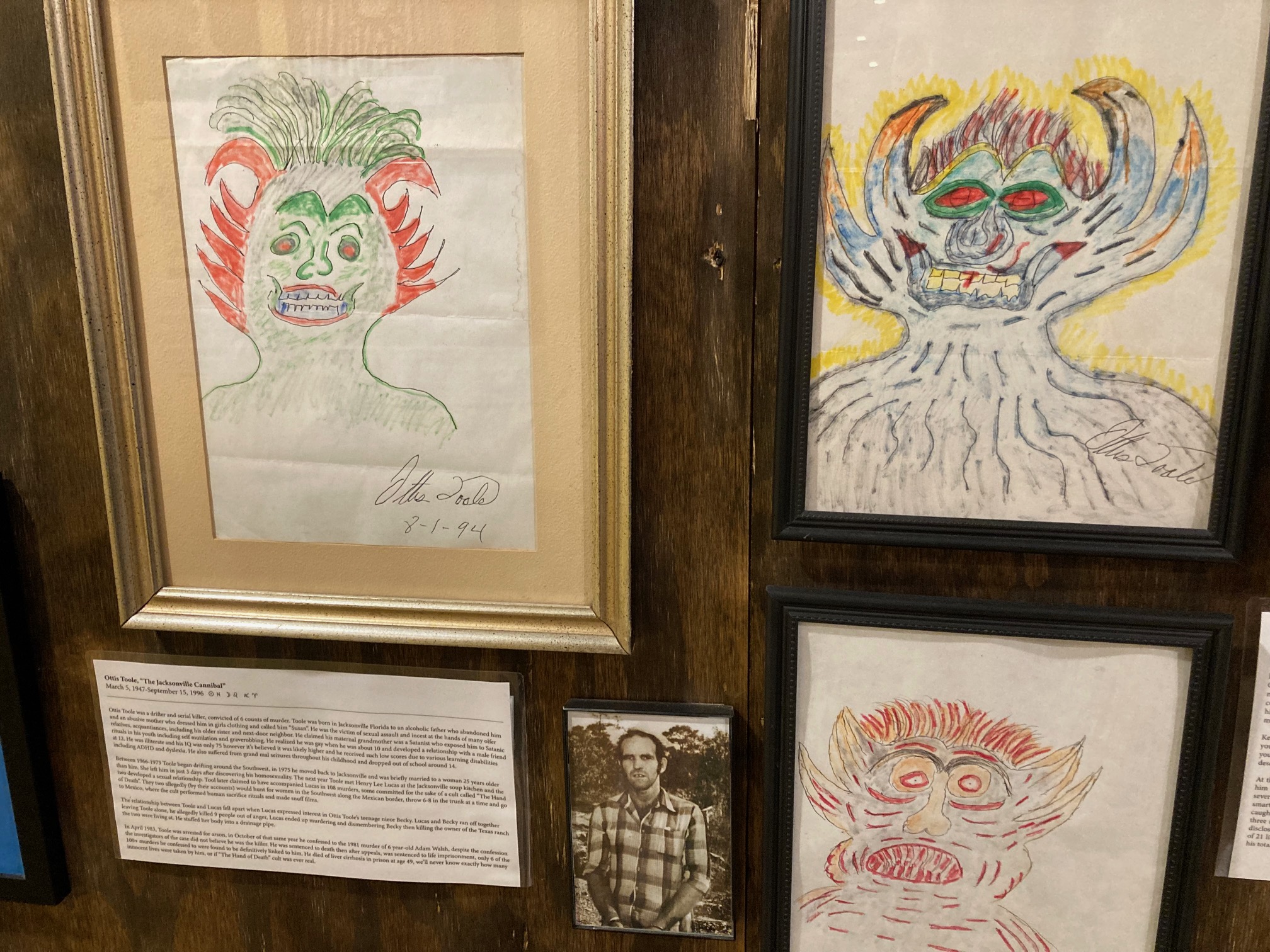

But there are more walls, with art by more killers. Arthur Shawcross, the so-called Genesee River Killer, confessed in 1990 to strangling eleven women. Here is his drawing of a wolf. Henry Lee Lucas, the so-called Confession Killer whose claims of over 600 murders have been largely discredited, was nonetheless convicted of killing his mother and two others. Here is his sentimental painting of a floppy-eared puppy next to a pot of flowers. Lucas’s friend and sometime partner Ottis Toole was convicted of six murders. Here are his childlike drawings of horned, red-eyed demons. Here are drawings by Richard Ramirez, the so-called Night Stalker. Here are portraits by Samuel Little, believed to be the most prolific serial killer in the United States. And more.

The stuffiness of the windowless room is suddenly oppressive; I’m breathing dust comprised of pollen, soil, bacteria, hair and dead skin cells. I have to take notes and pictures. I have to get out.

◊

Months later, after I returned home, Ryan Graveface and I exchanged a few emails, but after I sent him a list of questions, he stopped responding. You can find other interviews with him online. You can read about his interest in serial killers and the macabre, how he changed his name after it came to him in a dream.

My emails did not mention that Ryan Graveface and I had met before. When I was in Savannah in 2016, my host took me to Graveface Records and introduced us; Graveface was polite but preoccupied, so I walked around the store. The museum would not open for another four years, and racks of vinyl shared space with animal skulls and taxidermy. Inside a glass case, one of John Wayne Gacy’s Pogo self-portraits saluted with its balloons.

I’d heard a rumor on a true crime podcast that after Gacy realized how much money he could make by selling his paintings, he recruited his fellow inmates to form a kind of artistic assembly line. One man would fill in the blue around Pogo’s eyes, another the red of his mouth, and so on until Gacy added his signature. If true, this practice would explain the repetitive paint-by-numbers quality of Gacy’s work. But when I mentioned this rumor to Graveface, he bristled. “I have a certificate of authenticity!” he snapped, pointing to a piece of paper inside the glass case. I didn’t push it, and my host and I soon left for the bakery next door.

The Graveface Museum website offers free certificates of authenticity “to anyone who is attempting to purchase a Gacy painting from a random internet seller.” The site says that “the market is FLOODED with fakes,” but with Graveface’s access to Gacy’s logbooks, they can verify the serial numbers of any paintings.

That is, they can verify that a painting was sold by Gacy. But did his hand hold the brush that created it? If he lied for years about his crimes, about the essence of who he was, why wouldn’t he lie about a canvas? I wonder whether a man who lived this kind of double life, both pillar of the community and remorseless killer, can be considered in any way “authentic.”

◊

It goes without saying—doesn’t it?—that serial killer art is objectively terrible. There’s no depth of composition or color, no complexity or nuance of expression. There’s only the self, or whatever version of the self the artist has decided to project. Some, like Ottis Toole and the so-called Gainesville Ripper Danny Rolling, go for shock, sketching scenes of torture or demons. Their drawings look like something a teenage Black Sabbath fan might have doodled in his spiral notebook. Others, like Gacy and Henry Lee Lucas, go for irony, depicting bright, innocent clowns and animals and cartoons. “Look,” they seem to be saying, “I have a sensitive side, just like you.”

The allure of the artwork isn’t the art itself, but the monster who created it. Think of the portraits by George W. Bush and the attention they received when an email hacker posted several images in 2013. Art critics and comedians alike took potshots at Bush’s bathtub self-portrait, but the former president seems to have been encouraged by the attention; since then, he has published two books of his oil portraits. While some reviews were positive, others called his paintings “kitschy” and “inelegant.” My favorite review, published in The Ithacan, described his book Out of Many, One: Portraits of America’s Immigrants as “awful art made by an even more awful person.” Nevertheless, the book was a #1 New York Times bestseller.

Perhaps a more apt comparison is to elephants, gorillas, dogs, and other animals taught to paint. They’ve learned to imitate their human trainers, taking up brushes in hand or mouth and dabbing color onto canvas as they’ve seen people do. Animals who do this receive praise, perhaps a favorite food. Their paintings sell for thousands of dollars.

Many states have passed laws preventing convicted criminals from profiting from their crimes; some have determined that profits from book and movie rights should go to victims and their families. The technical term for such legislation is a “notoriety-for-profit law,” but the more familiar term is a “Son of Sam law.” Today these laws are mostly used to prevent the online sale of criminals’ artwork, letters, and personal items. The term for these items, coined in the early 2000s by then-director of the Houston Police Department’s Crime Victims Office Andy Kahan, is “murderabilia.”

For thirty-five years, the New York State Department of Corrections hosted an annual art show in Albany. A corrections spokesperson said the “Corrections on Canvas” show was “designed to allow inmates to show that during incarceration, they were finding positive ways to use their time in a manner that was felt contributed to rehabilitation.” Inmates were allowed to keep half of the proceeds from the sale of their art, while the other half was donated to the state Crime Victims Board. However, after a portrait of Princess Diana, created by serial killer Arthur Shawcross, sold for $500 in 2002, there was an uproar. Relatives of Shawcross’s victims–eleven women whom he raped, strangled, and mutilated–protested vehemently, and the art show was discontinued. The executive director of the Correctional Association of New York called the ban of inmate art sales a “blow to the rehabilitative process, at least for those inmates who produce attractive art.”

◊

A few hours after leaving the Graveface Museum, I board a boat that ferries me to an unspoiled barrier island, where I spend days taking long walks, talking about poetry, and hand-feeding carrots and apples to semi-tame donkeys. For two months, I avoid looking at the ghoulish pictures on my phone.

But I can’t help thinking about them and wondering why I find them so troubling. I’ve been a consumer of true crime all my life, and I spend hours each week watching documentaries and listening to podcasts about violent acts. The first thing I do after checking into any hotel room is to turn the TV to Forensic Files. The soothing repetition of its decades-old reruns instantly makes a strange place feel familiar. So why am I unsettled by the art made by convicted killers?

The intimacy, for one thing. Seeing a brush or pencil stroke calls too vividly to mind the hand that created it, as well as other things that hand has done. Here is a canvas or a sheet of paper held by a person who not only enacted some of the worst horrors one human can inflict on another, but who also seems to have taken pleasure in those horrors. For some visitors to the museum, that intimacy must be thrilling. For me, it’s repulsive.

True crime culture is having a moment of self-reckoning, trying to correct its history of glamorizing violence, especially the violence of serial killers. There’s an increasing focus on victims, and a self-expiating repetition of the mantra that victims and survivors are real people. Very little of that self-awareness is included in the Graveface displays; most of the artworks are accompanied by a short biography of the killers who created them, but they rarely mention victims. When victims are named, their names are buried in graphic descriptions of what they suffered.

Nevertheless, the market for serial killer art and other murderabilia remains robust, with websites like Serial Killers Ink and Murderauction.com offering artwork, letters, and other personal items belonging to or associated with convicted murderers. A few weeks after Alex Murdaugh’s conviction for murdering his wife and son, items belonging to his family were sold at auction. There doesn’t seem to have been anything qualifying as “art” in the sale–the closest thing was a set of pillows monogrammed with Maggie Murdaugh’s initials–but buyers bid hundreds of dollars for everyday items like Yeti cups and beer koozies. A mounted rack of deer antlers reportedly sold for $10,000.

Alex Murdaugh is serving two consecutive life sentences without the possibility of parole at the McCormick Correctional Institution in South Carolina. Among the mandatory rehabilitative classes at the prison are anger management, victim impact, creative writing, and art.