» Interview

Distance and Desire: A Conversation with Yasmina Din Madden

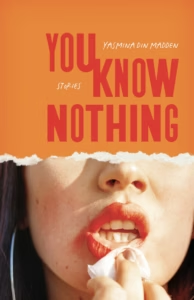

You Know Nothing: Stories

You Know Nothing: Stories

Yasmina Din Madden

Curbstone Books

$24.00

Publication date: February 15, 2026

Burke: What was it like gathering these stories together into a collection? How did you go about creating cohesive themes among forty-one short stories?

Madden: I found it fairly easy to gather these stories into a collection given that the themes of body, womanhood, family, rage, unknowability, distance, and desire made themselves apparent to me during the writing process and just kept showing up again and again.

Burke: What was your process for organizing the stories? As a reader, I was particularly interested in the throughline of the Vietnamese American family introduced at the beginning of the collection. What motivated you to scatter that family’s story and context?

Madden: I think the tensions that exist in this family echo out into many of the other stories in the collection—the inability to fully know or understand even those closest to us, our inability to not fully understand even our own actions. The frustration and anger the matriarch of this family feels at not being fully seen or understood are emotions and tensions that, many of the other female protagonists in the collection experience. These particular stories are scattered throughout the collection because they, like the other stories in the book, speak to overarching tensions in the collection as a whole—meaning I did not see a particular value in placing them all in one section of the collection. But as you note, the opening story in the collection centers on this family and the story that closes the book also centers on the matriarch of this family—I knew I wanted this family to bookend the collection. I really wanted to have this particular woman and mother—who is doing the best she can under complex circumstances—to have the last word.

Burke: Beyond recurring characters like Lily and her family, were there other plot connections that you were hoping for the reader to make?

Madden: I’m not sure I’d call them plot connections, but I would say the connective tensions I mention above—tensions associated with the body, womanhood, family, rage, unknowability, distance, and desire—were certainly important to how I structured the collection. I hope that connectivity comes through to readers over the course of reading these stories.

Burke: I’m curious about your relationship with speculative fiction. For the most part, this collection of short stories remains aligned with a feasible reality. However, there are a few short stories that make full use of unreality, such as “A Woman of Appetites” or “Destruction Myth.” What makes speculative/heightened elements essential in this collection?

Madden: The surreal details of the stories you mention, along with “Trimmed” and “When Georgia Simpson Awakes,” were the most natural and truest ways for me to come at the specific tensions of womanhood and existing in a female body. In terms of “Destruction Myth, I found the use of speculative details and the tone of this particular piece essential in underscoring how ridiculous our attitudes are toward the environmental disasters taking place before our eyes.

Burke: How does being a professor influence the stories you write? Beyond some of the stories being from the perspectives of teachers, the process of teaching and how lessons on life or reality are learned felt like a recurring theme.

Madden: Teaching university students has a huge influence on my writing, not so much in terms of content, though you’re absolutely right, there are a lot of stories that include a kind of teaching or lesson—I hadn’t even noticed that! Students don’t influence what I write (not consciously anyway) but they certainly influence how I think and feel about writing. I’m energized by my students’ willingness to take risks in their writing, like the glee many of them exhibit when they try out a second-person imperative point of view for the first time. I love seeing how students respond to reading and writing hermit crab flash essays—which is, typically, with excitement and a hunger to push themselves and experiment more in their writing. Most of all, seeing a student discover something—about themselves or the world and the people around them—through their writing is the best and a constant reminder of why I write.

Burke: This is primarily a collection of fiction, yet “How to Be Your Mother’s Best Daughter” was initially published as nonfiction! When I was first reading through the collection, I assumed that this essay fit into the Vietnamese American family’s narrative, and I think it still can, but it is an exciting complication to know that this work is also nonfiction. How close to heart are characters like Lily, Elyse, and the mother?

Madden: Those characters are very close to the heart, and, yes, that piece was first published as nonfiction—too many good lines (that sounds so obnoxious!) to pass up including this narrative in the collection.

Burke: In “A Gook, Not a Chink” and “Five Things You Should Know About Number Five,” the protagonists have their identities incorrectly simplified by outside observers. How does this experience of being simplified or misinterpreted relate to the collection’s title?

Madden: Great question. ‘You know nothing’ is a line of dialogue from the opening story, uttered by the matriarch of the Vietnamese American family. For me, this line encapsulates so many of the tensions in this collection—being reduced or simplified by someone, as you point out, and also the tensions or challenges many of the characters in this collection experience: feeling unknowable, believing they know someone else in their entirety, believing someone doesn’t have the first clue about who they are, or feeling someone close to them cannot be known.

Burke: Beyond bigotry and lazy racism, I’m curious to know what your opinions are on the ways that Asian Americans have accepted the impreciseness of their own identity. As a Korean American, I am able to relate to many of the experiences of the Vietnamese American family in stories like “Splinter” and “Then Go to Paris, I Say.” At the same time, I recognize that there are cultural and personal contexts that inform these shared experiences centered around belonging. Are monolith identifiers like ‘Asian American’ too simplifying?

Madden: Absolutely on monolith identifiers. My godmother is Korean American. She is the closest thing I have to a second mother. While there are clear overlaps in my mother and my auntie’s experiences, there are also major differences, and their ethnic identities—Vietnamese and Korean—are essential to who they are. I don’t know if I can speak to Asian Americans accepting the impreciseness of their own identity, as my own experience is not one of acceptance. But I do see what you mean in terms of how Asian Americans have had to, historically, accept this impreciseness as a way to assimilate. It seems, to me, that this acceptance was perhaps more necessary for my mother and godmother’s generation given the time period and given the Korean and Vietnam wars. But I think for my own generation, using our specific ethnic identity is natural and perhaps not loaded with some of the challenges other generations have faced.

Burke: Womanhood is explored from a variety of angles across most of the stories in this collection. Women’s bodies are the center of some of the most speculative elements in this collection. In “A Woman of Appetites,” the protagonist is able to devour people; in “Trimmed,” the protagonist mutilates herself to meet unrealistic beauty standards; and in “When Georgia Simpson Awakes,” the protagonist becomes a slug after cheating on her husband. Why focus on the body as the speculative conceit in these stories?

Madden: There are tensions and challenges to existing in a female body, or existing in a world where there are specific expectations of the female body or feminine behavior, along with our culture’s desire to restrict, legislate, and regulate women’s bodies; using the female body as a speculative conceit felt like the most visceral way to offer them in stories.

Burke: Mother-daughter relationships are a recurring dynamic in this collection. In “Splinter,” the perspective jumps between the mother and her daughters as the family fights. What motivates you to explore mother-daughter relationships, particularly in the context of this collection?

Madden: It’s one of my writerly obsessions, I guess. I keep going back for more—my novel centers on mothers and daughters too. Of course, my own experiences as a daughter and a mother inform many of these stories. In the context of this collection, I was particularly interested in exploring the fraught nature of intimate relationships—whether between mother and daughter, husbands and wives, lovers, siblings, or friends.

Burke: In stories like “Swan Dive” and “Reflections” parenthood is defined by a mix of love and fear. “Reflections” seems to stress how this knot of emotions and experiences can’t really be taught or prepared for. I’m curious to know how your own experience with parenthood has informed these stories.

Madden: For me, and I imagine a lot of parents, parenthood is a mix of so many emotions—pure love and joy along with a lot of fear and anxiety, moments and days with your child that come close to perfection mixed with some long-ass days full of mind-numbingly boring games. And so much more I can’t even get into here in a concise way. Exploring parenthood in some of these stories was a way to make sense of some of the feelings and questions I had about the role of a parent.

Burke: I found “That Baby” to be particularly interesting, as it explores both divorce and a broken mother-daughter relationship in which the damage has long since been done. The protagonist of the story is alone, yet there is a clear sense of hope for the protagonist to find some way to fix the damage. What makes a relationship irreparable? What makes a relationship salvageable?

Madden: Oh man, I wish I knew the answer to these questions, but I don’t. Maybe a relationship that is irreparable is one in which one person in the relationship cannot or will not recognize a problem and their part in that problem, let alone try to work through it. The protagonist of “That Baby” recognizes her part in the demise of her relationship with her daughter, which I think allows (for her, at least) some semblance of hope that she might fix some of the damage.

Burke: Much of the conflict throughout relates to the collection’s title, to the limitations of our perspectives and lived wisdom that inherently leads to hurt. Yet in “At the Dog Park,” there is such a profound sense of community that is created with the other dog owners, a sense of community that is rooted beyond the context of who these people are. The other dog owners are strangers, yet they are family. I found myself comparing the bonds in this story to the alienation of Lily and Margot in “Rococo.” What does it mean to know someone?

Madden: Such a great observation about how these two stories demonstrate connection and alienation in unexpected ways. It should be Lily and Margot who demonstrate that unbreakable bond, not the random dog park crew. But I think that part of what I was exploring in Rococo was how the relationships with those closest to us, in this instance two sisters, have the potential for visceral moments of unknowability and distance because of the history, complexity, and shared experiences specific to intimate relationships.

Yasmina Din Madden

Yasmina Din Madden

Yasmina Din Madden is a Vietnamese American writer living in Iowa. Her story collection You Know Nothing, was published by Northwestern University Press in February 2026, and her writing has been published in Electric Literature, The Idaho Review, The Fairy Tale Review, and other journals. She won the 2022 Oxford Flash Fiction Prize, and her short stories have been finalists for The Iowa Review Award in Fiction and nominated twice for a Pushcart Prize. She is an Associate Professor of English at Drake University and is represented by Andrea Blatt at William Morris Endeavor, New York.