Spring 2020 Graduates for CRW

Fall 2020 Graduates for CRW

Fall 2020 Graduates for LCT

Chloe Johnson

Spring 2021

Chloe Johnson is graduating with an MA in English: Literary, Cultural and Textual Studies. Her research interests include women writers, women writers of color, Historical Fiction, and Film and Literature studies. In UCF’s 2020 English Symposium, “Casting Light and Creating Shadows,” she presented her paper on Ana Castillo’s So Far From God. After graduation, she plans to obtain her Teaching Certificate so she can teach high school English. She eventually wants to receive her Ph.D. and teach literature at the university level.

Kenneth Kimberly

Spring 2021

Kenneth Kimberly is graduating with an MA in the English: Literary, Cultural, and Textual Studies program. Throughout his undergraduate and graduate career, Kenneth engaged with a wide variety of topics but focuses his research primarily on posthuman and transhuman literary theories. After graduation, Kenneth intends to pursue a career in the gaming industry as a writer, as well as publication for his posthuman theory research paper “More Human Than Human: Posthumanism in Blade Runner 2049 and the Definition of Humanity” to expand his literary career.

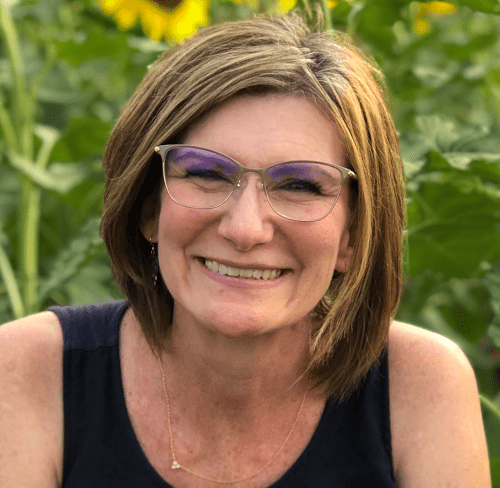

Amanda Cannon Jones

Spring 2021

Amanda Cannon Jones is graduating with an MA in English from the Literary, Cultural, and Textual Studies track. Her research interests include Native literacies and rhetoric. Amanda currently teaches high school English at Lake Highland Preparatory School in Orlando.

Jeanice Vacarizas

Spring 2021

Jeanice Vacarizas is an international student from the Philippines and Bahrain graduating with an MA in English from the Literary, Cultural, and Textual Studies program. Her conference papers, “Quaker Conversions: Sophia Hume and the Exhortation Narrative” and “Unapologetically Asian: Cultural Appropriation and Asian-American Identity Crises in Hip Hop” were featured in the 2018 and 2021 English Graduate Symposiums at UCF. Her research interests include Asian American literature, diaspora studies, feminist theory, and postcolonial theory. She currently works with international writing students at universities across the U.S. and hopes to pursue teaching and literary research in the future.

Sara Thames

Spring 2021

Sara Thames is graduating with an M.A. in English from the Literary, Cultural, and Textual Studies program. Throughout her studies, she has worked as a high school English Teacher for Colonial High School, as GTA for World Literature I, and as an instructor of Composition II at UCF. Her conference paper “Ophelia’s Swan Song: A Minor Discourse of Femininity in Hamlet” was featured in the 2020 Virtual English Symposium, and “Jude the Obscure: Hardy’s Treatise on Education” will be presented in the 2021 Symposium which she helped to organize. Sara hopes to continue working towards publication with the lines of inquiry explored in her thesis “Mutilated Masculinity: Intersections of Disability, Gender, and Mental Health in Modernist Fiction.” She desires to either continue her studies in an English Ph.D. program, or to continue teaching at the collegiate level.

Alaa Taha

Summer 2021

Alaa Taha has graduated with an M.A. in English: Literary, Cultural and Textual Studies. Her research interests include Arabic modernism and the postcolonial, which she discusses in her thesis “Toward an Arabic Modernism: Politics, Poetics, and the Postcolonial.” After graduation, she intends to pursue a career in fiction writing and hopes to teach at the collegiate level.

Jessica Lynch

Summer 2021

Jessica Lynch is graduating with a master’s degree from the Literary, Cultural, and Textual Studies program. She was honored with the College of Arts and Humanities 2019-2020 Award for Excellence as a Graduate Teaching Assistant. As a graduate teaching associate, Jessica has taught ENC 1102 for the 2020-2021 school year. Her areas of scholarly interest include feminist theory, culinary ephemera, and cultural studies.

Michael Parrish

Fall 2021

Thesis title: Hermeneutics of Hate: How Martin Luther’s Rhetorical Manipulation of the Greek Bible Led to His Anti-Judaic Treatise On the Jews and Their Lies

Literary, Cultural and Textual Studies M.A. – 2021 – Parrish

Jonathan Burnette

Fall 2021

Jonathan Burnette might graduate with a master’s degree from the Literary, Cultural, and Textual Studies program. His academic interests were Trauma Theory, Thing Theory, and Modernism.

Kendall Hall

Fall 2020

Kendall Hall completed her MA degree in English: Literary, Cultural, and Textual Studies at UCF while teaching various levels of high school English at local public and private schools. One of her primary literary interests is the Victorian era. Her conference paper, “Gender, Sexuality, and Freud: The Governess’s Liminality in The Turn of the Screw by Henry James” was featured in the 2019 Virtual English Graduate Symposium at UCF, and she continued her research in the program’s Capstone course this past semester. She now seeks to publish her work studying Henry James’s novellas, The Turn of the Screw and In the Cage and aspires to teach at the college level.

Lauren Porterfield

Fall 2020

Lauren Littler is graduating with her degree in Literary, Cultural, and Textual Studies while continuing her Masters of Fine Arts in Themed Experience from the UCF College of Theatre and Design. She aspires to become a show writer in the theme park industry and create shared experiences for Guests via immersive rides and unique restaurant experiences. Lauren’s specialties include creative writing, feminist theory, Renaissance poetics, and research. She has been writing for ten years, researching for six years, and hopes to expand her knowledge further during the years to come. She presented her paper, Red, White, and Blue: An Expression of Toxic Masculinity during the annual English Symposium, “Breaking Boundaries and Making Spaces”, at the University of Central Florida on March 2nd, 2018, as well as presented her paper on Disney Princesses and traditional versus rebellious ideology and organized in the Spring 2020 English Symposium. Her latest project was researching ancient Polynesian mythology and design for a presentation in her MFA program.

Sean Porterfield

Fall 2020

Sean Porterfield is graduating with an MA in English from the Literary, Cultural, and Textual Studies track. His research interests include poetry, modernism, and literary pedagogy. Sean currently teaches English at Freedom High School in Orlando, Florida.

Fall 2020 Graduates for Tech Comm

Kelly R. Fisher

Fall 2021

Kelly R. Fisher graduated from UCF in 2019 with her Bachelor’s degree in the English Literature program. Kelly will be receiving her Technical Communication Master’s degree in the Fall 2021 semester from UCF. Kelly is currently working on her second Master’s degree at UCF in the Instructional Design and Technology Program. Kelly is now writing a novel in honor of her late son.

Charles Lawrence

Fall 2021

Charles earned his bachelor’s degree from Michigan State University and has produced educational and training content for the disabled, the classroom, and for a health-specific, regional TV station’s social media. He has also written health-focused human-interest stories for newspapers and magazines. Inspired by science and health communicators, like Dr. Oliver Sacks, Charles became interested in translating complex health information for lay audiences. While pursuing his MA, Technical Communication at UCF, Charles became further inspired to begin a career in medical communication when his elderly father had hip replacement surgery, and Charles became his caregiver.

Charles is an active member of the American Medical Writers Association where he is the Florida chapter’s volunteer social media coordinator and recently presented a webinar to chapter members discussing medical rhetoric. When not immersing himself in medical communication related activities, Charles enjoys recreational running, playing his acoustic guitar, cultural satire, and creative wordplay.

Cailey Ness

Fall 2021

Cailey is originally from Crestview, Florida, and she earned her bachelor’s degree in Greek and Roman Studies from Millsaps College in Jackson, Mississippi. While in her undergraduate program, she worked as a writing consultant at her college’s Writing Center, which catalyzed her interest in pursuing an academic career in English. While completing her master’s program, she has worked as a case worker for the State of Texas.

After graduation, Cailey hopes to transition to teaching English and Composition at a community college. Eventually, she plans on pursuing a Ph.D. in Rhetoric and/or Technical Communication. Outside of academic pursuits, Cailey enjoys playing volleyball, reading, and cooking.

Malyn Brown

Fall 2021

Malyn Brown has a BA in English and an MFA in Creative Writing. She enrolled in the Technical Communication MA to develop her understanding of technical communication theory and its application. Malyn has experience teaching professional and creative writing courses. She also worked as a thesis advisor and course director in a Game Studies Masters program at a private university before transferring into her current position as an instructor in the Humanities.

She has extensive experience editing technical documentation and academic papers, as well as creating complex curriculum for adult learners using divergent instruction methods. In addition to teaching, she works as an independent contractor, composing, designing, and editing technical documentation for user experience research companies, game developers, and academic institutions.

Emily Smeltz

Fall 2021

Emily was born and raised in Lakeland, FL and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Business Administration and Management from Polk State College (PSC). To pursue her long-term goal of becoming a college professor, in 2017, she was hired as a Tutor and Teacher’s Assistant at PSC for upper-level English and Business courses. In fall 2021, she was successfully hired as an Adjunct Professor for Webber International University and PSC. She is currently teaching English courses at both institutions. Also in fall 2021, she joined University of Central Florida’s (UCF’s) Library team to produce Strategies for Conducting Inquiry-Based Literary Research, an open-resource textbook for UCF professors. She continued her education and graduated with a master’s degree in English Technical Communications at UCF in December 2021.

Along with her passion for teaching, she also has a natural talent for media production and successfully built several professional websites. Additionally, she has a love for writing, film production, and social sciences. In the near future, Emily hopes to continue her academic career by applying for overseas PhD programs.

Marisa Varela

Spring 2021

Marisa is originally from Ashburn, Virginia and earned her bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from Virginia Commonwealth University. After graduating, she moved to Florida to fulfill her dream of working at Walt Disney World. While taking graduate courses in Cognitive Sciences at UCF, she transitioned into a full-time roll in the office of Undergraduate Admissions.

After gaining work experience, she began her master’s degree in English – Technical Communication here at UCF in order to explore her love of writing and communications. Marisa enjoys intercultural and international technical communication, as well as visual communication and design. In her free time Marisa enjoys painting and digital art. After graduating, she hopes to find a career that incorporates her talents for writing, designing, and creating.

Emily Gruber

Summer 2021

Emily graduated from FSU in 2013 and shortly after was hired by a major US airline. In 2019 she enrolled in UCF’s Technical Communication MA program to further pursue her passion for researching and writing about complex subject matters. She enjoys the challenge of transforming technical information into readable and usable content, particularly in the context of government or procedural documentation. After graduating from UCF she will continue her career in aviation while working remotely as a technical writer/editor. When not on the clock Emily enjoys SCUBA diving, running marathons, and trying different vegan restaurants around the country.

Daniel Peters

Fall 2020

Dan currently works at the US Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) based out of Washington, DC and works in Florida most of the time although he travels to all the SEC locations across the United States. He works in the capacity of the Head of the Securities Faculty in which he creates, designs, develops, and delivers securities related curriculum to participants of the offices and divisions of the SEC. He does this in a classroom setting or an online setting (synchronously and asynchronously).

Dan has nearly 30 years in the financial services industry having worked mainly as a training director or senior officer, but has also held several securities licenses in support of the brokerage firms for which he worked. Dan also has 12 years of securities regulation experience in which he has trained numerous examiners who go into the field and examine the books and records of brokerage firms to assure compliance with federal securities laws, rules, and regulations.

Dan’s main purpose in pursuing a degree in technical communication is to enhance the skills he has acquired over the years that he has been in the securities industry. The main focus is technical writing, editing, and publishing of the coursework he creates.

Dan has BA in Elementary Education from Florida Atlantic and an MS in Open and Distance Learning from Florida State.

Originally from Miami, Florida, Dan began his professional career as a fifth-grade teacher which he did for 15 years before his transition to adult learning.

Audrey Ford

Fall 2020

Audrey Ford is a Tallahassee native. She earned her bachelor’s degree from the University of Central Florida in 2017 and has been working for the Florida Department of Education as a communications specialist since 2018. In her free time she enjoys reading a good book, writing, relaxing and planning fun activities for she and her 5 year old daughter.

After graduation, Audrey hopes to secure a communications position that integrates some of her main interests — education, racial equality, and intercultural and technical communication.

She’s excited to see where her master’s in technical communication from UCF will take her.