By Barry Mauer

How Are New Modes of Communication Invented?

The key to the invention of rock and roll was the development of a “personal culture,” which enabled the early rockers to think and communicate differently from commonly accepted modes. Both Elvis and Sam Phillips – Elvis producer at Sun Records – spent years, even before they began working together, developing their unique takes on American culture. Greil Marcus, in Mystery Train, writes: “Elvis created a personal culture out of the hillbilly world that was his as a given. Ultimately, he made that personal culture public in such an explosive way that he transformed not only his own culture, but America’s.” Marcus argues that the two genres of music Elvis recorded at Sun, blues and country, represent the contradictory impulses in American mythology between the individual and the community, between challenging limits and respecting those limits. Elvis and Phillips created music made from powerful paradoxes by crossing the boundaries of culture in the South.

One tactic for developing a personal culture is misreading (or mishearing). Michel Leiris, in his autobiography, The Rules of the Game, discusses how mishearing lyrics when he was a child and drawing his own meanings for songs led to his creation of imaginary worlds. Leiris’ theory of perverse listening explains much of how rock and roll pioneers such as Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly all heard something in the music of their day that few others heard, and then made use of their misreadings in imaginative ways. Phillips misread American roots music – blues and country – as potential pop music.

A key element of a personal culture is the “personal sacred.” Michel Leiris proposed that an individual can hold particular words, places, and things as being sacred, meaning that they have the power to transform elements of daily life from the mundane and practical to the magical. His theory of the “personal sacred” also explains how a personal culture emerges from dissonance, such as the dissonance between the private language of childhood and the public language of the mundane adult world. Additionally, Leiris provides a theory for how the “personal sacred” becomes the “public sacred,” or how private modes of thinking and communicating become public modes.

Sam Phillips’ personal sacred developed from his childhood fascination with the blues and he used it to define his feelings of discontent and dissonance with the culture around him. His vision came into focus when he encountered Beale Street in Memphis, a scene of bars with loud music, loud cars, and loud clothing, a fantasy of escape from a way of life that was itself becoming a way of life, where he sensed the possibility that the private culture he had nurtured could become public. Beale Street became Phillips’ “image of wide scope” (Howard Gruber’s term), an image that he retained throughout his creative life within his “network of enterprises” (another Gruber term), the related problems and projects that Phillips took up.

How does a creative person know whether his or her new product might be value? To answer this question, I examine Phillips’ choice to risk his scarce resources on an unproven Elvis. When Elvis came into the studio, he was singing ballads by Dean Martin and the Ink Spots in a quavering tenor. He had never performed live (except for his parents and a few friends, and at a couple of talent shows); he exhibited no knowledge of the rough blues music that Phillips had championed. Yet Phillips persisted. Two peculiarities strike me: no other studio would have taken a chance with Elvis, and none would have been able to produce the tremendous “original mistake” the was Elvis’s first single – “That’s All Right” and “Blue Moon of Kentucky.”

Phillips understood how the larger record companies operated and he did not want to operate the same way they did. Phillips chose amateur musicians and had them collaborate with professionals because he felt that only with amateurs could he get the freshness he sought. He became a psychologist, seeing potential in his musicians that they didn’t see themselves and bringing it out. Most of the musicians he recorded had profound inferiority complexes. Phillips showed them they could be worth as much as anyone else. He gave his musicians nearly impossible challenges, putting them in unusual musical contexts and making them “fight their way out.” His goal was the “original mistake” – the result that could not have been predicted. He seized the potential of the studio to capture those “mistakes” that most polished live acts would work to eliminate in rehearsals.

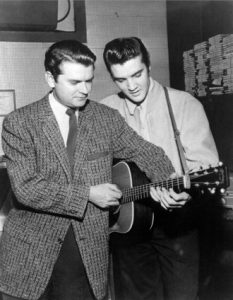

Phillips’ methods of selecting musicians and recording them was almost diametrically opposite to those of other producers at other studios, who used professional musicians exclusively. When Elvis started singing “That’s All Right” in the studio during a break, Phillips recognized that Elvis knew his secret language: the blues. Elvis had indicated no knowledge of this music until that point. From then on, Phillips knew the type of feeling he wanted from Elvis, something loose, free, and totally original. For instance, Elvis does “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” a bluegrass standard by Bill Monroe, as a rhythm tune; but it was originally a waltz. If Elvis had set out to do the song for a live act, he may have “goofed around” with it as a rhythm song, but likely would have settled on the waltz form, especially since the bluegrass genre was relatively conservative and was not often the subject of experiments. Elvis’s version is an accident of historic proportions, like the discovery of penicillin, but it could not have happened if Phillips had not been looking for something like it to happen. The “accidents” at Sun frequently occurred when Elvis and the band were taking a break from whatever they had been recording. Scotty Moore, the guitarist, typically began a riff – a repeated rhythmic figure on the guitar – and Elvis sang the lyrics of a blues or country song that would pop into his head; the lyric didn’t previously “go” with that riff.

The studio affords the possibility of capturing the opportune moment, just like the science laboratory does. But only if recording artists are prepared to recognize the value of fortuitous accidents will they be prepared to capitalize on them. Recordings and radio make opportune moments possible by supplying an archive of recordings from which an artist can draw materials, much like the library functions as an archive for scientists. Also like the laboratory, the studio allows for elaboration and refinement through revision. Once Phillips and Elvis had found a direction, they listened to playbacks of their first takes and used them as the basis for making further refinements, selecting some elements for emphasis, eliminating others. Finally, the studio allows for sounds that could not be reproduced live, such as Phillips’ haunting “slapback” echo.

Phillips developed his artists beyond what they themselves felt capable of doing. In this sense, he was a teacher in an electronic studio, fostering creativity and growth in his pupils while developing innovative uses of the technologies at his disposal. Phillips helped Elvis develop as an artist (while developing his own talents as a producer) over Elvis’ brief year-and-a-half stay at Sun Records.

When Elvis was drafted into the army in 1958, his music was not recognizably rockabilly anymore, but mostly novelty songs, movie soundtracks, and the like. Greil Marcus argues that the music did not have to “crystallize” the way it did, and that there is still untapped possibility for cultural inovation in the Sun singles.

More resources

- Gruber, Howard, Contemporary Approaches To Creative Thinking. New York: Atherton Press, 1962.

- Leiris, Michel, The Rules of the Game: Scratches (Rules of the Game/Michel Leiris, 1). The Johns Hopkins University Press; Johns Hopkins ed edition (April 1, 1997)

- Marcus, Greil, Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘N’ Roll Music. Plume Books; 4th Rev edition (May, 1997)