On February 10, the UCF History Department will host a Faculty Book Talk in the Morgridge International Reading Center’s Gallery. Department chair and associate professor Peter Larson, associate lecturer David Head and associate professor John M. Sacher will discuss their recent publications, with topics ranging from medieval England to Civil War-era America.

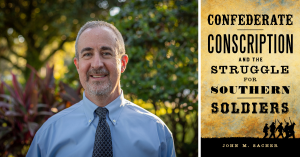

Sacher’s new book, Confederate Conscription and the Struggle for Southern Soldiers, is the first comprehensive examination of the southern draft program in nearly 100 years. The program constituted the first national conscription law in United States history, eliciting strong responses from southerners. The book examines Confederate identity through the lens of this conscription law and provides insight to the internal strains within the South.

We sat down with Sacher to discuss his interest in Civil War history, key points from his book, and what he’s most excited to share with readers at the upcoming event:

What inspired your interest in Civil War History?

When I was a sophomore at Notre Dame, I was an accounting major. I had always enjoyed history, and I joined the History Book Club. Luckily for me, one of my first selections was James McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, which is still considered the best history of the Civil War. I read it, and I was hooked. I switch my major to history, and I decided I would keep studying it until I needed to get a “real” job. Luckily, 30 years later, that day has not yet come.

Additionally, I consider the Civil War to be the most pivotal event in US History. Not only do almost 700,000 men die (perhaps as many as in all the rest of America’s wars combined), but it establishes the fact that states cannot secede from the Union and dissolve the nation. Also, if one considers the key issues of the Civil War — race relations and the relative power of the federal government versus the states — one can see that those key issues remain at the forefront of the national debate today, over 150 years after the war ended.

How did reactions about the conscription law vary among Southerners?

Conscription was a three-year process, and reactions changed over time and depended on where one lived and what their home situation was like. While I contend the measure was not universally hated, it was not universally celebrated either. Southerners possessed loyalties to their family, community, state and nation. For some, these loyalties worked in tandem — serving in the Confederate army and fending off Union invaders protected their families. Others, however, saw these loyalties in opposition. For a Floridian, accepting conscription and joining Lee’s army in Virginia might seem like the wrong choice if it meant leaving their sick wife, aging parents and six children by themselves.

What are some common misconceptions about the conscription law?

One of the main reasons I wrote this book was to combat the many misconceptions about the law. At first glance, the law appears to blatantly favor the wealthy. It allowed drafted men to provide substitutes in their place and gave anyone who owned 20 or more slaves an exemption. Given that, historians generally contend it drove a rift in the Confederacy between non-slaveholders and slaveholders, with the former rapidly giving up the Civil War.

The reality is not that simple. Substitution had a long history in American military culture, and the exemption for slaveholders was more about crop production and fear of slave rebellion than simply favoring the rich. Once I dove into the subject, I discovered conscription was more debated than hated. Southerners wanted to ensure that everyone did their share, while recognizing that while many men had to enter the army, others would have to remain home to make sure that both soldiers and civilians were fed, clothed and taken care of.

Plus, historians far too often talk about the conscription law as a single measure. In reality, the law changed at least five times in an effort to find the perfect, and maybe impossible, balance between the army and the home front. Even the controversial provisions were altered — substitution was banned, and the planter’s exemption was coupled with so many restrictions that it was hard for most planters to qualify for it.

What do you hope readers take away from your book?

Conscription, like all historical subjects, is complicated. Ideally, we need to consider it from the perspective of 19th-century southerners which means (1) that measures (such as substitution and the planter exemption) that shock us today were not necessarily shocking to them; (2) that many people who opposed the law did so because they considered themselves loyal Confederates (not because they were disloyal to their nation); (3) that just because the Confederacy lost, it does not mean that the conscription failed as a policy. As long as the Union used all its superior resources, the outnumbered Confederacy did not have enough men to fight and farm at the same time.

What are you excited to share at the upcoming Faculty Book Talk?

The human side of this story. For example, I’ve discovered great sets of letters from husbands in the army to their wives at home related to the purchase of substitute soldiers. In one case, a wife — with four kids at home and pregnant with her fifth — wants her husband to purchase a substitute and come home. Yet, he considers that to be a shameful course of action and he refuses. In another case, a husband chastises his wife for not working hard or quickly enough to gather the money to buy him a substitute, ultimately complaining that no one at home loves him. As you might imagine, the letters exchanged in these instances are fascinating to discover. Couples fought over what was best for the families and for the nation. The personal and the political, the home front and the battlefront become intertwined in ordinary lives.

To hear more about Sacher’s new book, along with the works of Larson and Head, RSVP to the Faculty Book Talk by emailing history@ucf.edu by February 7. Learn more about Confederate Conscription and the Struggle of Southern Soldiers in LSU Press’ Facebook Live Author Series event featuring Sacher.